Owen Jones writes: peak out now, decent Tories, or forever be damned for your complicity. Zac Goldsmith is gratuitously exploiting anti-Muslim prejudice in order to win this Thursday’s London mayoral election. His campaign has secured its place in the history books, joining a political hall of shame along with the Tories’ infamous racist 1964 Smethwick byelection and the homophobic Liberal Bermondsey byelection campaign in 1983. There are no excuses. Lifelong Conservative Peter Oborne has described Goldsmith’s campaign as “the most repulsive I have ever seen as a political reporter”. Former Conservative candidate Shazia Awan has denounced the campaign as “racist”. “This is not the Zac Goldsmith I know,” says Tory Baroness Warsi. “Are we Conservatives fighting to destroy Zac or fighting to win this election?” A number of erstwhile Conservative voters have contacted me to share their revulsion. For other Tories not to follow their lead leaves them sharing the blame.

Confronting those on your own side is not easy, but it is sometimes necessary. For the last few days I have been pilloried as an establishment lackey, a stooge of the Israeli government, a rightwing careerist and a sell-out. Why? Because I condemned what Jeremy Corbyn rightly described as Ken Livingstone’s “unacceptable” comments, backed the leadership’s suspension of the former London mayor, and supported their commendable decision to launch an inquiry into antisemitism. I do not turn a blind eye to allegations of antisemitism because they involve my own political tribe. The vast majority of leftwing activists I know are violently opposed to antisemitism, but the left can have no complacency when it comes to the menace of racism.

Racism is not an issue of point-scoring to me. It is deadly serious. I do not look at Goldsmith’s poisonous campaign and feel any pleasure, any excitement that its bigotry can be used for political advantage. I am left deeply frightened by it. Frightened because the Tories wouldn’t be doing it unless focus groups and polling suggests it works. Frightened because it’s happening in 2016. Frightened because of the hurt it is causing to Muslims, the damage it is inflicting to community cohesion, and that a horrible lesson is being taught about what happens when a Muslim stands for prominent public office – which will undoubtedly only aid recruitment efforts by extremists. [Continue reading…]

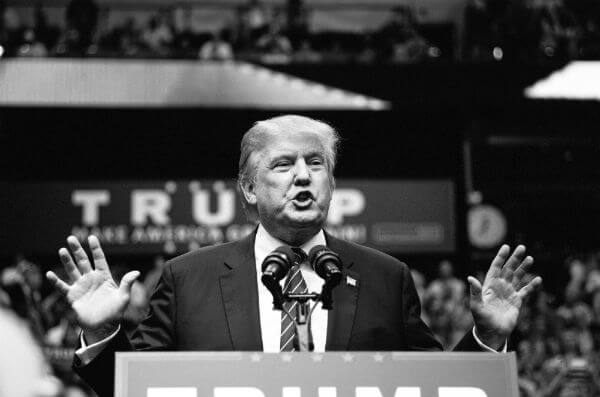

In race for London mayor, Trump’s anti-Muslim playbook seems to be failing Zac Goldsmith

Robert Mackey writes: Stop me if you’ve heard this one: An outsider politician who owes his station in life to the hundreds of millions he inherited from his father is running a failing campaign for office based on stoking fear of Muslims.

The word “failing” — as in 20 points down in the polls days before the election — is a clue that we are speaking about someone other than Donald Trump.

In this case, the politician’s name is Zac Goldsmith, and he is the millionaire scion of a prominent British family. He was thought of, until recently, as a mild-mannered Conservative member of Parliament, known mainly for his environmentalism and his sister’s friendship with the late Princess Diana.

For the past two months, however, he has generated waves of disgust and, polls suggest, not much sympathy, by pursuing a mayoral campaign filled with racially divisive innuendo about the supposed danger of electing his Labour Party rival, Sadiq Khan, a son of Pakistani Muslim immigrants.

The heavier the defeat for #NastyZac on Thursday, the longer it will be before the Tories dare to run a vile, racist campaign again. Vote!

— Pete Sinclair (@pete_sinclair) May 2, 2016

Things reached something of a crescendo over the weekend, when Goldsmith — advised by a political consultant whose website boasts that he was “described by Newt Gingrich as the U.K.’s own ‘Lee Atwater’” — published a dog-whistle appeal to voters in the Mail on Sunday, a right-wing tabloid, that implied Khan, a moderate member of Parliament, would somehow fail to defend the British capital from Islamist terrorists. [Continue reading…]

Trump, Le Pen and the enduring appeal of nationalism

Mark Mazower writes: The nation-state is basically no more than two centuries or so old, and in some places it is much younger than that. Yet the ideal of sovereign independence and political community it enshrines retains enormous appeal even in the face of the economic threat posed by globalisation. The new nationalisms seek to defend against this threat. The liberalisation of trade and capital flows may have started to equalise wealth across continents but they have brought a new degree of inequality within countries, eroded the prospects of middle-class life and finished off what was left of working-class communities in the old 19th-century industrial heartlands of the west in particular.

This is why today’s nationalist revival is so prominent in the west itself and why on both sides of the Atlantic the answer, if there is one, to the new sirens of nationalism will be found not in decrying it as a form of political idiocy — populism by another name — but rather in developing alternative visions of national wellbeing. In particular we need to recover the capacity to see the national and the international as necessary complements. The pro-European nationalist and the patriotic internationalist will then perhaps re-emerge as possibilities, rather than the contradictions-in-terms they presently seem.

Ironically, it is the parties of the far-right in the EU that come closest to this — coalescing around the slogan of a “Europe of fatherlands”. The real problem is not so much with the idea as with what they in particular would do with it. Their version is heavy on anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim rhetoric; the alternative is not European federalism but something that stresses economic rather than racial solidarity, a return to some form of role for national governments in long-range investment planning, and a return to fiscal instruments for economic recovery rather than the current total reliance on central banks. That too would be a form of nationalism, internationalist in spirit, ethnically inclusive rather than repressive, and — as it happens — much closer than anything currently on offer to the mix of policies that underpinned European integration in its early and highly successful decades. [Continue reading…]

A surprising number of Americans dislike how messy democracy is. They like Trump

John R. Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse write: Donald Trump’s candidacy – or more to the point, his substantial and sustained public support — has surprised almost every observer of American politics. Social scientists and pundits note that Trump appeals to populists, nativists, ethnocentrists, anti-intellectuals and authoritarians, not to mention angry and disaffected white males with little education.

But few have noticed another side of Trump’s supporters. A surprising number of Americans feel dismissive about such core features of democratic government as deliberation, compromise and decision-making by elected, accountable officials. They believe that governing is (or should be) simple, and best undertaken by a few smart, capable people who are not overtly self-interested and can solve challenging issues without boring discussions and unsatisfying compromises.

Because that’s just what Trump promises, his candidacy is attracting those who think someone should just walk in and get it done. His message is that our country’s problems are straightforward. All we need is to get “great people, really great people” to solve them. No muss, no fuss, no need to hear or take seriously opposing viewpoints. Trump’s straight-talking, unfiltered, shoot-from-the-hip style promises a leader who will take action – instead of working toward a consensus among competing interests. That sounds perfect to the millions of Americans who are just as impatient with standard democratic procedures. [Continue reading…]

How the kleptocrats’ $12 trillion heist helps keep most of the world impoverished

David Cay Johnston writes: For the first time we have a reliable estimate of how much money thieving dictators and others have looted from 150 mostly poor nations and hidden offshore: $12.1 trillion.

That huge figure equals a nickel on each dollar of global wealth and yet it excludes the wealthiest regions of the planet: America, Canada, Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

That so much money is missing from these poorer nations explains why vast numbers of people live in abject poverty even in countries where economic activity per capita is above the world average. In Equatorial Guinea, for example, the national economy’s output per person comes to 60 cents for each dollar Americans enjoy, measured using what economists call purchasing power equivalents, yet living standards remain abysmal.

The $12.1 trillion estimate — which amounts to two-thirds of America’s annual GDP being taken out of the economies of much poorer nations — is for flight wealth built up since 1970.

Add to that flight wealth from the world’s rich regions, much of it due to tax evasion and criminal activities like drug dealing, and the global figure for hidden offshore wealth totals as much as $36 trillion.

In 2014 the net worth of planet Earth was about $240 trillion, which means about 15 percent of global wealth is in hiding, significantly reducing the capital available to spur world economic growth. [Continue reading…]

Nick Turse: It can’t happen here, can it?

Every now and then, I teach a class to young would-be journalists and one of the first things I talk about is why I consider writing an act of generosity. As they are usually just beginning to stretch their writerly wings, their task, as I see it, is to enter the world we’re already in (it’s generally the only place they can afford to go) and somehow decode it for us, make us see it in a new way. And who can deny that doing so is indeed an act of generosity? But for the foreign correspondent, especially in war zones, the generosity lies in the very act of entering a world filled with dangers, a world that the rest of us might not be capable of entering, or for that matter brave enough to enter, and somehow bringing us along with them.

I thought about this recently when I had in my hands the first copy of Nick Turse’s new Dispatch Book, Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead: War and Survival in South Sudan, and flipped it open to its memorable initial paragraph, one I already new well, and began to read it all over again:

“Their voices, sharp and angry, shook me from my slumber. I didn’t know the language but I instantly knew the translation. So I groped for the opening in the mosquito net, shuffled from my downy white bed to the window, threw back the stained tan curtain, and squinted into the light of a new day breaking in South Sudan. Below, in front of my guest house, one man was getting his ass kicked by another. A flurry of blows connected with his face and suddenly he was on the ground. Three or four men were watching.”

Nick, TomDispatch’s managing editor and a superb historian as well as reporter, spent years in a war-crimes zone of the past to produce his award-winning book, Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. It was a harrowing historical journey for which he traveled to small villages on the back roads of Vietnam to talk to those who had experienced horrific crimes decades earlier. In 2015, however, on his second trip to South Sudan, a country the U.S. helped bring into existence, he found himself in an almost unimaginable place where the same kinds of war crimes were being committed right then and there in a commonplace way, where violence was the coin of the realm, and horrors of various sorts were almost guaranteed to be around the next corner. In his new book, he brings us with him into such a world in a way that is deeply memorable. Ann Jones, author of They Were Soldiers, calls him “the wandering scribe of war crimes.” And she adds, “Reading Turse will turn your view of war upside down… There’s no glory here in Turse’s pages, but the clear voices of people caught up in this fruitless cruelty, speaking for themselves.”

Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead is, I think, the definition of an act of generosity. Nick has just returned from his latest trip to South Sudan and today’s post gives you a sense of the ongoing brutalities and incongruities of life there (and here as well). Tom Engelhardt

Donald Trump in South Sudan

What trumps the horrors of a hellscape? The Donald!

By Nick TurseLEER, South Sudan — I’m sitting in the dark, sweating. The blinding white sun has long since set, but it’s still in the high 90s, which is a relief since it was above 110 earlier. Slumped in a blue plastic chair, I’m thinking back on the day, trying to process everything I saw, the people I spoke with: the woman whose home was burned down, the woman whose teenage daughter was shot and killed, the woman with 10 mouths to feed and no money, the glassy-eyed soldier with the AK-47.

Then there were the scorched ruins: the wrecked houses, the traditional wattle-and-daub tukuls without roofs, the spectral footprints of homes set aflame by armed raiders who swept through in successive waves, the remnants of a town that has ceased to exist.

Solitary confinement is ‘no touch’ torture, and it must be abolished

Chelsea E Manning writes: Shortly after arriving at a makeshift military jail, at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, in May 2010, I was placed into the black hole of solitary confinement for the first time. Within two weeks, I was contemplating suicide.

After a month on suicide watch, I was transferred back to US, to a tiny 6 x 8ft (roughly 2 x 2.5 meter) cell in a place that will haunt me for the rest of my life: the US Marine Corps Brig in Quantico, Virginia. I was held there for roughly nine months as a “prevention of injury” prisoner, a designation the Marine Corps and the Navy used to place me in highly restrictive solitary conditions without a psychiatrist’s approval.

For 17 hours a day, I sat directly in front of at least two Marine Corps guards seated behind a one-way mirror. I was not allowed to lay down. I was not allowed to lean my back against the cell wall. I was not allowed to exercise. Sometimes, to keep from going crazy, I would stand up, walk around, or dance, as “dancing” was not considered exercise by the Marine Corps.

To pass the time, I counted the hundreds of holes between the steel bars in a grid pattern at the front of my empty cell. My eyes traced the gaps between the bricks on the wall. I looked at the rough patterns and stains on the concrete floor – including one that looked like a caricature grey alien, with large black eyes and no mouth, that was popular in the 1990s. I could hear the “drip drop drip” of a leaky pipe somewhere down the hall. I listened to the faint buzz of the fluorescent lights.

For brief periods, every other day or so, I was escorted by a team of at least three guards to an empty basketball court-sized area. There, I was shackled and walked around in circles or figure-eights for 20 minutes. I was not allowed to stand still, otherwise they would take me back to my cell. [Continue reading…]

ISIS files reveal Assad’s deals with militants

Sky News reports: Islamic State and the Assad regime in Syria have been colluding with each other in deals on the battleground, Sky News can reveal.

Our exclusive investigation into leaked secret IS files suggests one piece of co-operation was over the ancient city of Palmyra.

The files also show that the militant group has been training foreign fighters to attack Western targets for much longer than security services had suspected.

The revelations underscore fears in the United States that a network of sleeper cells is spread across Europe, avoiding detection, and is planning further Paris- and Brussels-style assaults.

IS defectors, meanwhile, have told Sky News that Palmyra was handed back to government forces by Islamic State as part of a series of cooperation agreements going back years.

New letters obtained by Sky News, in addition to the massive haul of 22,000 files handed over last month, appear to confirm this. [Continue reading…]

Third U.S. combat death comes as American troops edge closer to the front lines in Iraq

The Washington Post reports: At the base of a rocky ridge rising from the surrounding farmland, the barrels of American artillery poke out from under camouflage covers, their sights trained on Islamic State-held positions.

Less than 10 miles from the front lines in the push toward the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, the U.S. outpost, known as Firebase Bell, is manned by about 200 Marines.

“Having them here has raised the morale of our fighters,” said Lt. Col. Helan Mahmood, the head of a commando regiment in the Iraqi army, as his truck bumped along the dirt track that divides his base from the American encampment, ringed by razor wire and berms.

“If there’s any movement from the enemy, they bomb immediately,” he said.

The new firebase is part of a creeping U.S. buildup in Iraq since troops first returned to the country with a contingent of 275 advisers, described at the time by the Pentagon as a temporary measure to help get “eyes on the ground.”

Now, nearly two years later, the official troop count has mushroomed to 4,087, not including those on temporary rotations, a number that has not been disclosed. [Continue reading…]

Turkish journalists accuse Erdoğan of media witch-hunt

The Guardian reports: Can Dündar appears in good spirits for a man facing espionage charges and a possible life sentence.

The editor of Cumhuriyet, one of the last remaining bastions of media opposition to Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, had appeared in court that morning over a documentary he produced on government corruption. It is one of two cases against him – in February, he was released from prison pending a spying trial over a story on arms shipments to Syria.

“Turkey has never been a paradise for journalists but of course not a hell like this,” he said in an interview in his office. “Nowadays being a journalist is much more dangerous than ever and needs courage and self-confidence.

“It’s a kind of witch-hunt … like McCarthyism in the US in the 1950s.”

Turkish journalists say local media outlets are facing one of the worst crackdowns on press freedoms since military rule in the 1980s. Prosecutors have opened close to 2,000 cases of insults to the president since Erdoğan took office in 2014, prominent journalists appear in court two or three times a week, Kurdish journalists are beaten or detained in the country’s restive south-east and foreign journalists have been harassed or deported. [Continue reading…]

Spain issues warrants for top Russian officials, Putin insiders

RFE/RL reports: A Spanish judge has issued international arrest warrants for several current and former Russian government officials and other political figures closely linked to President Vladimir Putin.

The named Russians include a former prime minister and an ex-defense minister, as well as a current deputy prime minister and the current head of the lower house of parliament’s finance committee.

The Spanish documents detail alleged members of two of Russia’s largest and best-known criminal organizations — the Tambov and Malyshev gangs — in connection with crimes committed in Spain including murder, weapons and drug trafficking, extortion, and money laundering.

But Spanish police also conclude that one of the gangs was able to penetrate Russian ministries, security forces, and other key government institutions and businesses with the help of an influential senior legislator. [Continue reading…]

Music: Can — ‘She Brings the Rain’

Peace and the politics of outrage

“Any religion worth talking about is essentially political and any politics worth talking about has some vision of transcendence and of the mystery of human life,” said the Jesuit priest, antiwar activist and poet, Daniel Berrigan, at the time of the trial of the Plowshares Eight in 1981. Berrigan died on Saturday at the age of 94.

In 2006, noting that the “short fuse of the American left is typical of the highs and lows of American emotional life,” Berrigan said: “It is very rare to sustain a movement in recognizable form without a spiritual base.”

This absence of a spiritual base, expressed through commonly held values, can be seen as one of the defining characteristics of the politics of dissent in the post 9/11 era.

The commonalities around which shifting forms of unity have emerged and dissolved have invariably come in the form of shared outrage and hatred.

We decide who we stand with by flagging what we stand against:

- American Empire

- Western Imperialism

- Zionism

- Capitalism

- Neoliberalism

- Militarism

- Corporate power

- Globalization

- National security state

- Mass surveillance

- Mass incarceration

- Police brutality

- Racism

- Xenophobia

- Islamophobia

- Homophobia

- Sexism

But the affirmative common ground gets far less clearly defined if articulated at all.

Where humanitarianism and internationalism once prevailed, anti-interventionism has become one of the most frequently voiced principles.

Opposition to America imposing its values on the world, has come to mean the plight of people who lives and basic rights are in peril can often be ignored.

It seems we have less responsibility to make this a better world than to merely claim we have done it little harm.

It is as though the measure of a life well lived be that it is of no consequence as we each swear to a political Hippocratic oath.

Indeed there are those who now view the concept of human rights as so tainted that it functions as nothing more than a justification for war.

Out of this emerges for some a libertarian insularity where the least harm each of us might do is to mind our own business, and for others an isolationist social-justice realism which says, take care of the folks at home instead of trying to fix the world.

In a political context where it’s much safer to assume an adversarial posture and stand up against our nameable enemies, what’s much harder is to move beyond divisions and to focus instead on the greatest deficits in our world: a lack of love and kindness and the absence of a widely embraced vision of a better future.

It’s much easier to unify around what we stand against.

Bring love and kindness into the equation and most of the boundaries we use to define our political identities become less secure; our opponents cannot so easily be made other.

Consider, for instance, the issue of Palestine.

If viewed through a dispassionate political lens, we can talk about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in terms of self-determination, social justice, and anti-colonialism and yet as a human concern, empathizing with Palestinians being bombed in Gaza by Israelis is surely no different than responding with empathy to atrocities being carried out in Aleppo.

For those on the ground, the outcome of the bombing is no different and yet the fact that the former provokes global outcries while the later is met largely with global indifference speaks to something that few observers will dare state: their hatred for the perpetrators of the violence is more deeply rooted than they sympathy for the victims.

* * *

To recognize the political and social influence of Daniel Berrigan did not require that you shared his pacifism or his religious beliefs and yet his striking integrity derived from the fact that he was a living expression of religion and politics made indivisible.

In 2006, as Berrigan turned 85, he was interviewed by Chris Hedges for The Nation:

All empires, Berrigan cautions, rise and fall. It is the religious and moral values of compassion, simplicity and justice that endure and alone demand fealty. The current decline of American power is part of the cycle of human existence, although he says ruefully, “the tragedy across the globe is that we are pulling down so many others. We are not falling gracefully. Many, many people are paying with their lives for this.”

“The fall of the towers [on 9/11] was symbolic as well as actual,” he adds. “We are bringing ourselves down by a willful blindness that is astonishing.”

Berrigan argues that those who seek a just society, who seek to defy war and violence, who decry the assault of globalization and degradation of the environment, who care about the plight of the poor, should stop worrying about the practical, short-term effects of their resistance.

“The good is to be done because it is good, not because it goes somewhere,” he says. “I believe if it is done in that spirit it will go somewhere, but I don’t know where. I don’t think the Bible grants us to know where goodness goes, what direction, what force. I have never been seriously interested in the outcome. I was interested in trying to do it humanly and carefully and nonviolently and let it go.”

“We have not lost everything because we lost today,” he adds.

A resistance movement, Berrigan says, cannot survive without the spiritual core pounded into him by [Thomas] Merton. He is sustained, he said, by the Eucharist, his faith and his religious community.

“The reason we are celebrating forty years of Catonsville and we are still at it, those of us who are still living — the reason people went through all this and came out on their feet — was due to a spiritual discipline that went on for months before these actions took place,” he says. “We went into situations in court and in prison and in the underground that could easily have destroyed us and that did destroy others who did not have our preparation.”

During an interview in 1981, Berrigan was asked how he came to the “deep waters” — the spiritual perspective — that enabled his activism.

It’s a question of coming from somewhere, having some tradition available to you — some symbols, some worship, some common life… coming from somewhere better than America, because I don’t think America is anywhere to come from.

In a world where it has become so easy to denounce America and point to the extensive harm this nation has done as its imperial power ungracefully unwinds, the politics of outrage nevertheless evokes little sense of somewhere better than America.

The collapse of empire is nothing to celebrate if we lack a vision of something better to take its place.

How democracy can turn into tyranny

Andrew Sullivan writes: As this dystopian election campaign has unfolded, my mind keeps being tugged by a passage in Plato’s Republic. It has unsettled — even surprised — me from the moment I first read it in graduate school. The passage is from the part of the dialogue where Socrates and his friends are talking about the nature of different political systems, how they change over time, and how one can slowly evolve into another. And Socrates seemed pretty clear on one sobering point: that “tyranny is probably established out of no other regime than democracy.” What did Plato mean by that? Democracy, for him, I discovered, was a political system of maximal freedom and equality, where every lifestyle is allowed and public offices are filled by a lottery. And the longer a democracy lasted, Plato argued, the more democratic it would become. Its freedoms would multiply; its equality spread. Deference to any sort of authority would wither; tolerance of any kind of inequality would come under intense threat; and multiculturalism and sexual freedom would create a city or a country like “a many-colored cloak decorated in all hues.”

This rainbow-flag polity, Plato argues, is, for many people, the fairest of regimes. The freedom in that democracy has to be experienced to be believed — with shame and privilege in particular emerging over time as anathema. But it is inherently unstable. As the authority of elites fades, as Establishment values cede to popular ones, views and identities can become so magnificently diverse as to be mutually uncomprehending. And when all the barriers to equality, formal and informal, have been removed; when everyone is equal; when elites are despised and full license is established to do “whatever one wants,” you arrive at what might be called late-stage democracy. There is no kowtowing to authority here, let alone to political experience or expertise.

The very rich come under attack, as inequality becomes increasingly intolerable. Patriarchy is also dismantled: “We almost forgot to mention the extent of the law of equality and of freedom in the relations of women with men and men with women.” Family hierarchies are inverted: “A father habituates himself to be like his child and fear his sons, and a son habituates himself to be like his father and to have no shame before or fear of his parents.” In classrooms, “as the teacher … is frightened of the pupils and fawns on them, so the students make light of their teachers.” Animals are regarded as equal to humans; the rich mingle freely with the poor in the streets and try to blend in. The foreigner is equal to the citizen.

And it is when a democracy has ripened as fully as this, Plato argues, that a would-be tyrant will often seize his moment. [Continue reading…]

How the curse of Sykes-Picot still haunts the Middle East

Robin Wright writes: In the Middle East, few men are pilloried these days as much as Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. Sykes, a British diplomat, travelled the same turf as T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia), served in the Boer War, inherited a baronetcy, and won a Conservative seat in Parliament. He died young, at thirty-nine, during the 1919 flu epidemic. Picot was a French lawyer and diplomat who led a long but obscure life, mainly in backwater posts, until his death, in 1950. But the two men live on in the secret agreement they were assigned to draft, during the First World War, to divide the Ottoman Empire’s vast land mass into British and French spheres of influence. The Sykes-Picot Agreement launched a nine-year process — and other deals, declarations, and treaties — that created the modern Middle East states out of the Ottoman carcass. The new borders ultimately bore little resemblance to the original Sykes-Picot map, but their map is still viewed as the root cause of much that has happened ever since.

“Hundreds of thousands have been killed because of Sykes-Picot and all the problems it created,” Nawzad Hadi Mawlood, the Governor of Iraq’s Erbil Province, told me when I saw him this spring. “It changed the course of history — and nature.”

May 16th will mark the agreement’s hundredth anniversary, amid questions over whether its borders can survive the region’s current furies. “The system in place for the past one hundred years has collapsed,” Barham Salih, a former deputy prime minister of Iraq, declared at the Sulaimani Forum, in Iraqi Kurdistan, in March. “It’s not clear what new system will take its place.”

The colonial carve-up was always vulnerable. Its map ignored local identities and political preferences. Borders were determined with a ruler — arbitrarily. At a briefing for Britain’s Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, in 1915, Sykes famously explained, “I should like to draw a line from the ‘E’ in Acre to the last ‘K’ in Kirkuk.” He slid his finger across a map, spread out on a table at No. 10 Downing Street, from what is today a city on Israel’s Mediterranean coast to the northern mountains of Iraq.

“Sykes-Picot was a mistake, for sure,” Zikri Mosa, an adviser to Kurdistan’s President Masoud Barzani, told me. “It was like a forced marriage. It was doomed from the start. It was immoral, because it decided people’s future without asking them.” [Continue reading…]

How the ‘Green Zone’ helped destroy Iraq

Emma Sky writes: While the United States has been fixated on the Islamic State and the liberation of Mosul, the attention of ordinary Iraqis has been on the political unraveling of their own country. This culminated on Saturday when hundreds of protesters breached the U.S.-installed “Green Zone” at the heart of Baghdad for the first time and stormed the Iraqi parliament while Iraqi security forces stood back and watched. The demonstrators, supporters of radical Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, toppled blast walls, sat in the vacated seats of the parliamentarians who had fled and shouted out demands for the government to be replaced. A state of emergency was declared.

This incident should be a jarring alarm bell to Washington, which can no longer ignore the disintegration of the post-Saddam system it put in place 13 years ago. The sad reality is that Iraq has become ungovernable, more a state of militias than a state of institutions. As long as that state of affairs continues, even a weakened Islamic State, which has been losing territory and support, will find a home in Iraq, drawing on Sunni fears of corruption and incompetence by the Shia-dominated government.

The greatest threat to Iraq thus comes not from the Islamic State but from broken politics, catastrophic corruption, and mismanagement. Indeed there is a symbiotic relationship between terrorists and corrupt politicians: They feed off each other and justify each other’s existence. The post-2003 system of parceling out ministries to political parties has created a kleptocratic political class that lives in comfort in the Green Zone, detached from the long-suffering population, which still lacks basic services. There is no translation into Arabic of the term kleptocracy. But judging by the protesters chanting “you are all thieves,” they know exactly what it means. [Continue reading…]

How Moqtada al-Sadr could take down Iraq’s government

The Daily Beast reports: Hussain Jassim refused to leave the Green Zone, once considered the impenetrable citadel at the heart of Baghdad, until his leader Muqtada al-Sadr ordered him to do so. “We have entered parliament and we have broken it’s prestige in front of people because they are thieves, they deserve for that to happen to them,” Jassim told The Daily Beast.

He was one of thousands of angry protestors who on Saturday raided the Iraqi legislature, chasing MPs out of their own seats in government, and often assaulting or denouncing those not aligned with al-Sadr trying to run away from the melee. “We saw them fleeing from us,” Jassim said.

Some legislators stayed behind, trapped in the basement of the parliament for fear of not wanting to confront the angry crowd outside. There were even false reports that a few had repaired to the sprawling U.S. embassy complex, seeking refuge from their own countrymen.

Remarkably, Iraq’s security forces tolerated the demonstrators day-long occupation of a notorious no-go area in the capital. The protesters climbed over concrete blast walls and burst through cordons with ease. Some tear gas was used, but law enforcement the state mingled comfortably with those against whom they were meant to guard. “The security forces have dealt with us with a high sense of patriotism and responsibility,” Jassim said.

These protests were a long time going. Iraq’s public coffers are a sieve, where billions have vanished in the salaries of “ghost soldiers” or into the bank accounts of well-connected pols and their kin. Problematic enough in peacetime and during high global oil prices, economic crisis is 2016 has become a national security crisis, as state bankruptcy could easily damage or end the ongoing war against the Islamic State. [Continue reading…]

As bombs fall, Aleppo asks: ‘Where are the Americans?’

The Telegraph reports: Recovering in Turkey after a deadly air strike on a hospital in Aleppo, all that Abu Abdu Tebyiah could think about was the six children he had been forced to leave behind.

Mr Tebyiah was critically injured when the Syrian regime dropped three bombs on al-Quds hospital next to his house in the east of the city last Thursday.

He was one of a lucky few allowed over the border to receive treatment for his broken ribs and pelvis, wounds that would probably have killed him otherwise. But the 49-year-old shop owner was taken away so quickly that he had little chance to tell his rescuers that his children were waiting for him at home.

“They are too young to be on their own,” Mr Tebyiah told the Telegraph. “The government is using barrel bombs on our neighbourhood again, so I stopped them going to school. They are now in great danger.”

Mr Tebyiah said the only way to bring his children to Turkey, which closed its border to fleeing Syrians earlier this year, was to pay smugglers $500 for each child – money he did not have.

“I have to find a solution as soon as possible,” he said. “Or I don’t want to think what will happen.”

Fighting has intensified in Syria’s second city this week, claiming over 250 lives and ending in all but name a much-vaunted ceasefire agreed in February.

Now the opposition-controlled eastern side of Aleppo is braced for an offensive by Bashar al-Assad’s regime and his Russian and Iranian allies. If Assad succeeds in recapturing the whole of the city, it could change the course of the war.

As the regime’s bombs dropped on their houses, hospitals and schools, residents wondered where their supposed protectors, the Americans, were.

Many had been optimistic that the ceasefire, brokered by the United States and Russia, was the ray of hope that Aleppo needed after enduring four years of killing since Syria’s war came to the city in 2012. [Continue reading…]