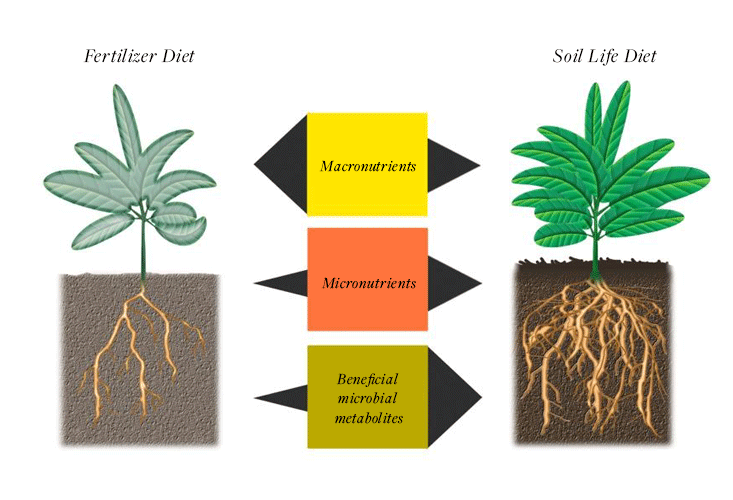

Anne Biklé and David R. Montgomery write: Most of us are familiar with the much-maligned Western diet and its mainstay of processed food products found in the middle aisles of the grocery store. Some of us beeline for the salty chips and others for the sugar-packed cereals. But we are not the only ones eating junk food. An awful lot of crops grown in the developed world eat a botanical version of this diet—main courses of conventional fertilizers with pesticide sides.

It’s undeniable that crops raised on fertilizers have produced historical yields. After all, the key ingredients of most fertilizers — nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) — make plants grow faster and bigger. And popular insecticides and herbicides knock back plant enemies. From 1960 to 2000, a time when the world’s population doubled, global grain production rose even more quickly. It tripled.

But there is a trade-off. High-yielding crops raised on a steady diet of fertilizers appear to have lower levels of certain minerals and nutrients. The diet our crops eat influences what gets into our food, and what we get — or don’t get — out of these foods when we eat them. [Continue reading…]

Author Archives: Attention to the Unseen

Music: Frank Woeste — ‘Warmer Regen’

Technology, the faux equalizer

Adrienne LaFrance writes: Just over a century ago, an electric company in Minnesota took out a full-page newspaper advertisement and listed 1,000 uses for electricity.

Bakers could get ice-cream freezers and waffle irons! Hat makers could put up electric signs! Paper-box manufacturers could use glue pots and fans! Then there were the at-home uses: decorative lights, corn poppers, curling irons, foot warmers, massage machines, carpet sweepers, sewing machines, and milk warmers all made the list. “Make electricity cut your housework in two,” the advertisement said.

This has long been the promise of new technology: That it will make your work easier, which will make your life better. The idea is that the arc of technology bends toward social progress. This is practically the mantra of Silicon Valley, so it’s not surprising that Google’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, seems similarly teleological in his views. [Continue reading…]

Music: Frank Woeste — ‘God Put a Smile Upon Your Face’

Why ‘natural selection’ became Darwin’s fittest metaphor

Kensy Cooperrider writes: ome metaphors end up forgotten by all but the most dedicated historians, while others lead long, productive lives. It’s only a select few, though, that become so entwined with how we understand the world that we barely even recognize them as metaphors, seeing them instead as something real. Of course, why some fizzle and others flourish can be tricky to account for, but their career in science provides some clues.

Metaphors, as we all by now know, aren’t just ornamental linguistic flourishes — they’re basic building blocks of everyday reasoning. And they’re at their most potent when they recast a difficult-to-understand phenomenon as something familiar: The brain becomes a computer; the atom, a tiny solar system; space-time, a fabric. Metaphors that tap into something familiar are the ones that generally gain traction.

Charles Darwin gave us both kinds, big winners and total flops. Natural selection, his best-known metaphor, is still a fixture of evolutionary biology. Though it’s not always recognized as a metaphor today, that’s exactly what it was to Darwin and his contemporaries. After all, evolution was a foreign and unwieldy concept. So Darwin set out to make it accessible by comparing it to a method employed in farmyards around the world.

For years, Darwin — a fancy pigeon breeder — obsessed over what he called artificial selection, what cattle-breeders, gardeners, and crop-growers did to create new varieties of plant and animal: allowing just the ones with desirable traits to reproduce. Darwin’s first-hand experience with breeding set the stage for his now-famous metaphoric leap. [Continue reading…]

‘Hobbits’ may have died out before the arrival of humans

Science News reports: Hobbits disappeared from their island home nearly 40,000 years earlier than previously thought, new evidence suggests.

This revised timeline doesn’t erase uncertainty about the evolutionary origins of these controversial Indonesian hominids. Nor will the new evidence resolve a dispute about whether hobbits represent a new species, Homo floresiensis, or were small-bodied Homo sapiens.

Hobbits vanished about 50,000 years ago at Liang Bua Cave on Flores, an island situated between Borneo and Australia’s northern coast, say archaeologist Thomas Sutikna of the University of Wollongong, Australia, and his colleagues.

Cave sediment dating to about 12,000 years ago, which lies just above soil that yielded H. floresiensis remains, provided an initial estimate of when these diminutive hominids with chimp-sized brains died out. But that sediment washed into the cave long after H. floresiensis was gone, covering much older, hobbit-bearing soil, the researchers report in the March 31 Nature. [Continue reading…]

Music: Chick Corea & Gary Burton — ‘Children’s Song #6’

Islam’s forgotten bohemians

Nile Green writes: Every year, thousands of festivals around the tombs of Sufi saints in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh demonstrate the vitality of Sufi poetry. Dotted throughout town and countryside, the shrines where these saints are buried still form the focus for the spiritual lives of tens of millions of Muslims. Their doors and rituals are open to people of any religious background; as a result, Sufi shrines in India still play an important role in the religious life of many Hindus and Sikhs. The work of the great Baba Farid, a 13th-century Punjab Sufi poet, also exemplifies this long history of religious co-existence, as his poems form the oldest parts of the Sikh scriptures.

Farid’s poems are still recited in Sikh temples around the world. In one of the verses from his Adi Granth (the sacred scripture or ‘First Book’ of Sikhism), Farid declares in rustic and homely Punjabi:

Ap li-ay lar la-ay dar darves say.

Translation: Those tied to Truth’s robe are true tramps on the doorstep.

The seeker after Truth must become a wandering beggar. The word Farid uses is darves, or ‘dervish’ – literally, a vagrant who goes from door to door. Read again that alliterative line of Punjabi: Ap li-ay lar la-ay dar darves say. It has the simple rhythm of repetition, the call of love’s beggar traipsing from house to house.

What the German philosopher Max Weber described as the disenchantment of the world, modernity’s discrediting of the supernatural and magical, has not been good for these beggars, these mystical troubadours, especially among the Muslim middle classes. Their pilgrimage places, however, retain mass appeal, especially among the large populations of poor and uneducated people. That is why fundamentalists, whether the Pakistani Taliban, the Saudi government or ISIS, have destroyed so many Sufi shrines and places of pilgrimage. The poetry sung at those places celebrates and advances an Islam that rejects political power, an Islam incompatible with the ambitions of religious fundamentalism. It is an Islam antithetical to political Islam, which sees political power as the foundation of religion. Although not all forms of Sufi Islam are non-political, the Sufism of the dervishes renounced political power as the most significant impediment on the long road to their divine beloved. It is a spirit of Islam still very much alive. [Continue reading…]

Music: Chick Corea — ‘Rumba Flamenco’

An American in Istanbul: Molly Crabapple on art and activism

Pacific Standard: “To draw is to objectify, to go momentarily to a place where aesthetics mean more than morality,” Molly Crabapple writes in her memoir, Drawing Blood, an addictive volume that I devoured a few weeks ago during a flight from Rome to Istanbul, the city that stands at the center of Crabapple’s fascination with what was once called “the Orient.” With her artwork already placed in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, her essays and illustrations published in venues like Vanity Fair and Vice, the 33-year-old artist is a curious composite of entrepreneur, revolutionary, and bohemian artist. The book is an account of Crabapple’s formation as an artist and political dissident, from her childhood in Long Island to teenage travels in Europe and the Middle East, to her mature return to New York in the heart of Occupy protests at Zuccotti Park.

Drawing Blood is designed as a notebook, where Crabapple sketches her life story in both words and lines — 30 short chapters featuring snappy episodes from the artist’s life crammed together with illustrations done in the style of a courtroom sketch. The book’s central characters and places, meanwhile — a group of intellectuals, artists, sex workers, refugees, dissidents, bookstores, and streets who have helped shape Crabapple’s conscience — come to life in the book’s sketches, wherein Crabapple seems to have painted each at the moment she first came into contact with them. [Continue reading…]

Why science and religion aren’t as opposed as you might think

By Stephen Jones, Newman University and Carola Leicht, University of Kent

The debate about science and religion is usually viewed as a competition between worldviews. Differing opinions on whether the two subjects can comfortably co-exist – even among scientists – are pitted against each other in a battle for supremacy.

For some, like the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, science and religion represent two separate areas of enquiry, asking and answering different questions without overlap. Others, such as the biologist Richard Dawkins – and perhaps the majority of the public – see the two as fundamentally opposed belief systems.

But another way to look at the subject is to consider why people believe what they do. When we do this, we discover that the supposed conflict between science and religion is nowhere near as clear cut as some might assume.

Music: Chick Corea & Stefano Bollani — ‘Picture in Black & White’

Music: Chick Corea & Stefano Bollani — ‘Windows’

Slaughter at the bridge: Uncovering a colossal Bronze Age battle

Andrew Curry reports: About 3200 years ago, two armies clashed at a river crossing near the Baltic Sea. The confrontation can’t be found in any history books — the written word didn’t become common in these parts for another 2000 years — but this was no skirmish between local clans. Thousands of warriors came together in a brutal struggle, perhaps fought on a single day, using weapons crafted from wood, flint, and bronze, a metal that was then the height of military technology.

Struggling to find solid footing on the banks of the Tollense River, a narrow ribbon of water that flows through the marshes of northern Germany toward the Baltic Sea, the armies fought hand-to-hand, maiming and killing with war clubs, spears, swords, and knives. Bronze- and flint-tipped arrows were loosed at close range, piercing skulls and lodging deep into the bones of young men. Horses belonging to high-ranking warriors crumpled into the muck, fatally speared. Not everyone stood their ground in the melee: Some warriors broke and ran, and were struck down from behind.

When the fighting was through, hundreds lay dead, littering the swampy valley. Some bodies were stripped of their valuables and left bobbing in shallow ponds; others sank to the bottom, protected from plundering by a meter or two of water. Peat slowly settled over the bones. Within centuries, the entire battle was forgotten. [Continue reading…]

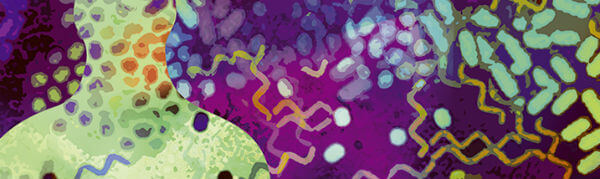

The microbes that make us who we are

Most people, however strongly they might hold to what they regard as a scientific view of life — that we are biological organisms, products of evolution, not destined for a supernatural afterlife — nevertheless most likely have a sense of identity that does not easily accommodate the idea that our thoughts and feelings are influenced by bacteria. Indeed, such an idea might sound delusional.

Yet this is what is increasingly clearly understood: that the body is not the abode of an elusive self; nor that human experience can be reduced to the aggregation of cascades of action potentials producing a neural symphony; but that this seemingly unitary being is in fact a community in which what we are and what lives inside our body cannot be separated.

Science magazine reports: The 22 men took the same pill for four weeks. When interviewed, they said they felt less daily stress and their memories were sharper. The brain benefits were subtle, but the results, reported at last year’s annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, got attention. That’s because the pills were not a precise chemical formula synthesized by the pharmaceutical industry.

The capsules were brimming with bacteria.

In the ultimate PR turnaround, once-dreaded bacteria are being welcomed as health heroes. People gobble them up in probiotic yogurts, swallow pills packed with billions of bugs and recoil from hand sanitizers. Helping us nurture the microbial gardens in and on our bodies has become big business, judging by grocery store shelves.

These bacteria are possibly working at more than just keeping our bodies healthy: They may be changing our minds. Recent studies have begun turning up tantalizing hints about how the bacteria living in the gut can alter the way the brain works. These findings raise a question with profound implications for mental health: Can we soothe our brains by cultivating our bacteria?

By tinkering with the gut’s bacterial residents, scientists have changed the behavior of lab animals and small numbers of people. Microbial meddling has turned anxious mice bold and shy mice social. Rats inoculated with bacteria from depressed people develop signs of depression themselves. And small studies of people suggest that eating specific kinds of bacteria may change brain activity and ease anxiety. Because gut bacteria can make the very chemicals that brain cells use to communicate, the idea makes a certain amount of sense.

Though preliminary, such results suggest that the right bacteria in your gut could brighten mood and perhaps even combat pernicious mental disorders including anxiety and depression. The wrong microbes, however, might lead in a darker direction.

This perspective might sound a little too much like our minds are being controlled by our bacterial overlords. But consider this: Microbes have been with us since even before we were humans. Human and bacterial cells evolved together, like a pair of entwined trees, growing and adapting into a (mostly) harmonious ecosystem.

Our microbes (known collectively as the microbiome) are “so innate in who we are,” says gastroenterologist Kirsten Tillisch of UCLA. It’s easy to imagine that “they’re controlling us, or we’re controlling them.” But it’s becoming increasingly clear that no one is in charge. Instead, “it’s a conversation that our bodies are having with our microbiome,” Tillisch says. [Continue reading…]

Music: Arve Henriksen — ‘Bayon’

Dramatic change in the moon’s tilt may help us trace the origin of water on Earth

By Mahesh Anand, The Open University

Astronomers have found evidence that the axis that the moon spins around shifted billions of years ago due to changes in the moon’s internal structure. The research could help explain the strange distribution of water ice near the lunar poles – the tilt would have caused some of the ice to melt by suddenly exposing it to the sun while shadowing other areas. It could also help us pinpoint craters that have been shadowed for so long that they contain water ice from early in the solar system.

Identifying recent and ancient water ice in specific craters will help scientists map the history of water on the moon. And as the moon likely formed from the Earth colliding with a planet 4.5 billion years ago, it may also help explain how the Earth got its water – a longstanding puzzle.