On September 11, 2001, America froze in shock and the shock was followed by a mix of fear, anger and bewilderment.

Yet for some, the first response was also the enduring response: a knowing dread that what followed would be far worse than what just happened; that America’s reaction would be wildly disproportionate and vastly more destructive than the events of that day.

Some of us had the luxury of holding that dispassionate wide-angle perspective from the comfort of distance — I lived on the West Coast at that time. But there were others who saw what was coming even while still breathing the dust from the collapsed Twin Towers. Tom Engelhardt was such an observer and has been chronicling the 9/11 fallout ever since.

Dan Froomkin reviews a distillation of those observations captured in Tom’s new book, The American Way of War; How Bush’s Wars Became Obama’s.

Neither Iraq nor Afghanistan could possibly be mistaken for successes, and yet the neocons have succeeded in creating a political climate in which, as Engelhardt explains, war and security are somehow seen as being synonymous. As a result, any alternative to war has become tantamount to diminishing our security — and is therefore politically untenable. Alternatives to war get no serious hearing in modern Washington. And while the mainstream media apparently doesn’t find this the least bit strange, Engelhardt does.

He asks good questions about it. “What does it mean,” he writes, “when the most military-obsessed administration in our history, which, year after year, submitted ever more bloated Pentagon budgets to Congress, is succeeded by one headed by a president who ran, at least partially, on an antiwar platform, and who then submitted an even larger Pentagon budget?”

Indeed, it would appear that unless things change dramatically, we are condemned to enduring war, in the form of a Global War on Terror (GWOT) that never ends. At least now you know why.

Engelhardt devotes some time to chronicling the nation’s massive, insatiable war machine — and our country’s role as arms supplier to the world. (When’s the last time you saw anything in the news about that?)

He exposes what he calls the “garrisoning of the planet” by literally countless U.S. military bases around the globe — bases that drain our treasury while angering our allies and energizing our enemies.

“Basing is generally considered here either a topic not worth writing about or an arcane policy matter best left to the inside pages for the policy wonks and news junkies,” Engelhardt writes. “This is in part because we Americans — and by extension our journalists — don’t imagine us as garrisoning or occupying the world; and certainly not as having anything faintly approaching a military empire.”

He chronicles the extraordinary barbarity of the air war and the “collateral damage” it wreaks; an enterprise now made even more soulless as death is unleashed from drones operated by pilots hundreds or thousands of miles away.

Rather than look away as most of us do, Engelhardt faces right up to the greatest, most horrible irony of the post 9/11 period: that we did to ourselves “what al-Qaeda’s crew never could have done. Blinding ourselves via the GWOT, we released American hubris and fear upon the world, in the process making almost every situation we touched progressively worse for this country.”

“Jewish terrorists have just blown up the King David Hotel!” This short message was received by the London Bureau of United Press International (UPI) shortly after noon, Palestine time. It was signed by a UPI stringer in Palestine who was also a secret member of the Irgun. The stringer had learned about Operation Chick but did not know it had been postponed for an hour. Hoping to scoop his colleagues, he had filed a report minutes before 11.00. A British censor had routinely stamped his cable without reading it.

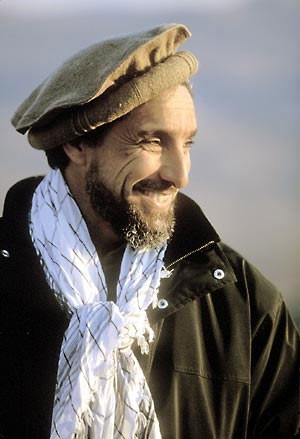

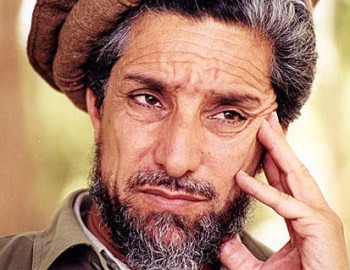

“Jewish terrorists have just blown up the King David Hotel!” This short message was received by the London Bureau of United Press International (UPI) shortly after noon, Palestine time. It was signed by a UPI stringer in Palestine who was also a secret member of the Irgun. The stringer had learned about Operation Chick but did not know it had been postponed for an hour. Hoping to scoop his colleagues, he had filed a report minutes before 11.00. A British censor had routinely stamped his cable without reading it. As Americans prepare to mark the Sept. 11 anniversary, with many still struggling to come to terms with the cataclysm of that day, Afghans are passing through their own harrowing remembrance, of an attack that was overshadowed for the rest of the world by what happened two days later in the United States. Only four men died on Sept. 9 — the 49-year-old Mr. Massoud, an aide and the assassins — but there has been little healing of the wounds the killers inflicted on the hearts and the hopes of millions of his countrymen.

As Americans prepare to mark the Sept. 11 anniversary, with many still struggling to come to terms with the cataclysm of that day, Afghans are passing through their own harrowing remembrance, of an attack that was overshadowed for the rest of the world by what happened two days later in the United States. Only four men died on Sept. 9 — the 49-year-old Mr. Massoud, an aide and the assassins — but there has been little healing of the wounds the killers inflicted on the hearts and the hopes of millions of his countrymen. Let me correct a few fallacies that are propagated by Taliban backers and their lobbies around the world. This situation over the short and long-run, even in case of total control by the Taliban, will not be to anyone’s interest. It will not result in stability, peace and prosperity in the region. The people of Afghanistan will not accept such a repressive regime. Regional countries will never feel secure and safe. Resistance will not end in Afghanistan, but will take on a new national dimension, encompassing all Afghan ethnic and social strata.

Let me correct a few fallacies that are propagated by Taliban backers and their lobbies around the world. This situation over the short and long-run, even in case of total control by the Taliban, will not be to anyone’s interest. It will not result in stability, peace and prosperity in the region. The people of Afghanistan will not accept such a repressive regime. Regional countries will never feel secure and safe. Resistance will not end in Afghanistan, but will take on a new national dimension, encompassing all Afghan ethnic and social strata.