Gen Stanley McChrystal looks bemused at the sight of President Obama in a bomber jacket during a surprise visit to Afghanistan in March, 2010.

A Rolling Stone profile of Gen Stanley McChrystal due out on Friday “was a mistake reflecting poor judgment and it should have never happened,” the commander of US forces in Afghanistan now says.

It was a mistake to say what he and his staff said, or it was a mistake to make these remarks in the presence of a journalist?

The incident reveals the ambivalence Americans feel when it comes to the institutional power at the center of American democracy. Whatever keeps the wheels of Washington working smoothly, it isn’t candor.

Coming as I do from a country that has a real and ancient monarchy (for which I have little respect), during twenty-some years in the United States I’ve always viewed this country’s republican credentials with a certain measure of skepticism.

If at its conception America cast aside regal authority because of an unambiguous faith in the power of the people, why is it that so many Americans have such a gooey-eyed fascination with British royalty? Why the obsession with another form of royalty: celebrity? Why, in a supposedly egalitarian society, is such a high value attached to very visible displays of social status?

Americans seem to have had less interest in completely abandoning rule by a monarch than in modifying regal power and repackaging it in the quasi-regal institution of the presidency.

Having been crowned, a president always remains a president — even once out of office. He lives in a little palace, can never move around without being surrounded by a huge entourage of somewhat venal and sycophantic characters. And as in all forms of palace politics, those individuals who have wormed their way close to the center of power will do whatever they can to protect the status of the institution as they make frequent expressions of obeisance to the king-president.

But the concentration of power always involves the consolidation of power and so a president, just like any king, always needs to be on his guard, aware that one of his dukes or generals might pose a challenge.

Enter, Gen Stanley McChrystal.

McChrystal isn’t trying to stage a coup but he’s a repeat offender when it comes to upholding the most important principle in regal politics: never undermine the authority of the monarch or his highest officers.

National Security Adviser, Gen James Jones is a “clown.” Senior envoy Richard Holbrooke is a “wounded animal.” Joe Biden is “Bite me.” This is not language that can be uttered louder than a whisper in any palace.

As McChrystal heads to Washington for yet another dressing down, there’s one thing we can be sure of: President Obama won’t be wearing a bomber jacket when he lectures his top general. He’ll simply relying on the power of his throne — the Oval Office.

In his Rolling Stone profile of McChrystal, Michael Hastings writes:

The general prides himself on being sharper and ballsier than anyone else, but his brashness comes with a price: Although McChrystal has been in charge of the war for only a year, in that short time he has managed to piss off almost everyone with a stake in the conflict. Last fall, during the question-and-answer session following a speech he gave in London, McChrystal dismissed the counterterrorism strategy being advocated by Vice President Joe Biden as “shortsighted,” saying it would lead to a state of “Chaos-istan.” The remarks earned him a smackdown from the president himself, who summoned the general to a terse private meeting aboard Air Force One. The message to McChrystal seemed clear: Shut the fuck up, and keep a lower profile

Now, flipping through printout cards of his speech in Paris [in mid-April], McChrystal wonders aloud what Biden question he might get today, and how he should respond. “I never know what’s going to pop out until I’m up there, that’s the problem,” he says. Then, unable to help themselves, he and his staff imagine the general dismissing the vice president with a good one-liner.

“Are you asking about Vice President Biden?” McChrystal says with a laugh. “Who’s that?”

“Biden?” suggests a top adviser. “Did you say: Bite Me?”

When Barack Obama entered the Oval Office, he immediately set out to deliver on his most important campaign promise on foreign policy: to refocus the war in Afghanistan on what led us to invade in the first place. “I want the American people to understand,” he announced in March 2009. “We have a clear and focused goal: to disrupt, dismantle and defeat Al Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan.” He ordered another 21,000 troops to Kabul, the largest increase since the war began in 2001. Taking the advice of both the Pentagon and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he also fired Gen. David McKiernan – then the U.S. and NATO commander in Afghanistan – and replaced him with a man he didn’t know and had met only briefly: Gen. Stanley McChrystal. It was the first time a top general had been relieved from duty during wartime in more than 50 years, since Harry Truman fired Gen. Douglas MacArthur at the height of the Korean War.

Even though he had voted for Obama, McChrystal and his new commander in chief failed from the outset to connect. The general first encountered Obama a week after he took office, when the president met with a dozen senior military officials in a room at the Pentagon known as the Tank. According to sources familiar with the meeting, McChrystal thought Obama looked “uncomfortable and intimidated” by the roomful of military brass. Their first one-on-one meeting took place in the Oval Office four months later, after McChrystal got the Afghanistan job, and it didn’t go much better. “It was a 10-minute photo op,” says an adviser to McChrystal. “Obama clearly didn’t know anything about him, who he was. Here’s the guy who’s going to run his fucking war, but he didn’t seem very engaged. The Boss was pretty disappointed.”

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target.

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target. In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of

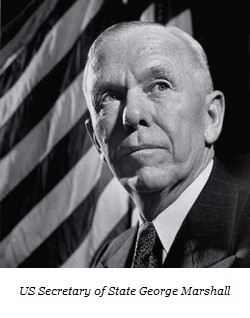

In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of  In early February of 2006, I submitted a book proposal about the wartime relationship between Generals George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower to a group of New York publishers. I had worked on the proposal for nine months and believed it would garner significant interest. Two weeks after the submission, I received my first response — from a senior editor at a major New York publishing firm. He was uncomfortable with the proposal: “Wasn’t Marshall an anti-Semite?” he asked. I’d heard this claim before, but I was still shocked by the question. For me, George Marshall was an icon: the one officer who, more than any other, was responsible for the American victory in World War Two. He was the most important soldier of his generation — and a man of great moral and physical courage.

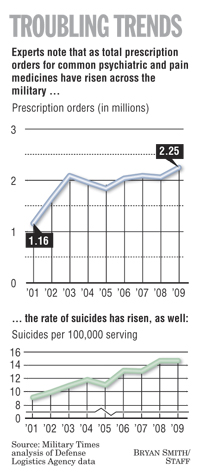

In early February of 2006, I submitted a book proposal about the wartime relationship between Generals George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower to a group of New York publishers. I had worked on the proposal for nine months and believed it would garner significant interest. Two weeks after the submission, I received my first response — from a senior editor at a major New York publishing firm. He was uncomfortable with the proposal: “Wasn’t Marshall an anti-Semite?” he asked. I’d heard this claim before, but I was still shocked by the question. For me, George Marshall was an icon: the one officer who, more than any other, was responsible for the American victory in World War Two. He was the most important soldier of his generation — and a man of great moral and physical courage. At least one in six service members is on some form of psychiatric drug.

At least one in six service members is on some form of psychiatric drug.

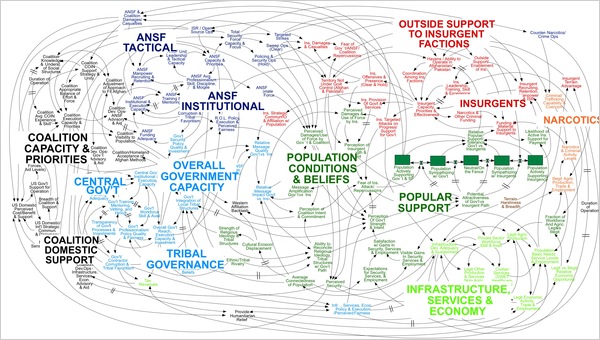

On January 16, two days after a killer earthquake hit Haiti, a team of senior military officers from the U.S. Central Command (responsible for overseeing American security interests in the Middle East), arrived at the Pentagon to brief JCS Chairman Michael Mullen on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The team had been dispatched by CENTCOM commander David Petraeus to underline his growing worries at the lack of progress in resolving the issue. The 33-slide 45-minute PowerPoint briefing stunned Mullen. The briefers reported that there was a growing perception among Arab leaders that the U.S. was incapable of standing up to Israel, that CENTCOM’s mostly Arab constituency was losing faith in American promises, that Israeli intransigence on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was jeopardizing U.S. standing in the region, and that Mitchell himself was (as a senior Pentagon officer later bluntly described it) “too old, too slow…and too late.”

On January 16, two days after a killer earthquake hit Haiti, a team of senior military officers from the U.S. Central Command (responsible for overseeing American security interests in the Middle East), arrived at the Pentagon to brief JCS Chairman Michael Mullen on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The team had been dispatched by CENTCOM commander David Petraeus to underline his growing worries at the lack of progress in resolving the issue. The 33-slide 45-minute PowerPoint briefing stunned Mullen. The briefers reported that there was a growing perception among Arab leaders that the U.S. was incapable of standing up to Israel, that CENTCOM’s mostly Arab constituency was losing faith in American promises, that Israeli intransigence on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was jeopardizing U.S. standing in the region, and that Mitchell himself was (as a senior Pentagon officer later bluntly described it) “too old, too slow…and too late.”