Middle East Eye reports: An Egyptian activist was found by the side of a desert road with his body bearing evidence of torture, relatives said, as security forces continued a wave of mass arrests ahead of demonstrations planned for Monday.

Khaled Abdel Rahman, from Alexandria, is in intensive care undergoing surgery after passersby discovered him on the side of a desert road on the outskirts of the capital Cairo, his sister Reem Abdel Rahman said.

“His body is covered in marks of beating and torture – the electric shocks applied to his genitals were so severe that they caused atrophy,” she wrote on Facebook.

Abdel Rahman was found on Friday afternoon, less than a day after he was arrested during a raid on his home by security forces, relatives said.

The raid was part of a wave of arrests undertaken by police in cities across Egypt ahead of Monday’s protests. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Arab Spring

Sisi’s stature melting away

David Hearst writes: President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has been burning the candle at both ends. Having burned his way through Egypt’s largest political party, the Muslim Brotherhood, Sisi went on to give secular liberals who supported his coup against Mohamed Morsi the same treatment: imprisonment, torture or banishment. A significant part of Egypt’s political and intellectual elite is now in exile. He has one source of legitimacy left – the international community. This week, he’s been burning his way through that.

Sisi’s week should have started on a high – the visit of the Saudi King Salman. After all the tension between the two countries (at the time of Salman’s succession, the pro-Sisi media declared the then crown prince not fit for office) and after all the reports of money from Saudi drying up, this should have been an occasion to silence all doubters: Salman was investing $22bn in Egypt. The Egyptian presidency described Salman’s visit as “crowning the close brotherly ties between the two countries.”

Salman’s visit had been much hyped, as indeed Sisi’s visit to Britain was in November last year. Sisi expected each to be a breakthrough of its kind. And yet during his visit to London, Cameron cancelled all British flights to Egypt as a result of the downing of a Russian airliner over Sinai, sounding the death knell of the Egyptian tourist industry. A similar disaster awaited Sisi in Salman’s visit. [Continue reading…]

Most young Arabs reject ISIS and think ‘caliphate’ will fail, poll finds

The Guardian reports: The vast majority of young Arabs are increasingly rejecting Islamic State and believe the extremist group will fail to establish a caliphate, a poll has found.

Only 13% of Arab youths said they could imagine themselves supporting Isis even if it did not use much violence, down from 19% last year, while 50% saw it as the biggest problem facing the Middle East, up from 37% last year, according to the 2016 Arab Youth Survey.

However, concern is mounting across the region as a chronic lack of jobs and opportunities were cited as the principal factor feeding terrorist recruitment. In eight of the 16 countries surveyed, employment problems were a bigger pull factor for Isis than extreme religious views.

The eighth annual survey provides a snapshot of the aspirations of 200 million people. It found that five years after the start of the Arab spring, most youngsters prioritise stability over democracy. Optimism that the region would be better off in the wake of the 2011 uprisings has been steadily declining.

In 2016, only 36% of young people said they felt the Arab world was in better shape following the upheaval, down from 72% in 2012. The majority (53%) agreed that maintaining stability was more important than promoting democracy (28%). In 2011, 92% of Arab youth said “living in a democracy” was their most cherished wish. [Continue reading…]

Everyone says the Libya intervention was a failure. They’re wrong

Shadi Hamid writes: Libya and the 2011 NATO intervention there have become synonymous with failure, disaster, and the Middle East being a “shit show” (to use President Obama’s colorful descriptor). It has perhaps never been more important to question this prevailing wisdom, because how we interpret Libya affects how we interpret Syria and, importantly, how we assess Obama’s foreign policy legacy.

Of course, Libya, as anyone can see, is a mess, and Americans are reasonably asking if the intervention was a mistake. But just because it’s reasonable doesn’t make it right.

Most criticisms of the intervention, even with the benefit of hindsight, fall short. It is certainly true that the intervention didn’t produce something resembling a stable democracy. This, however, was never the goal. The goal was to protect civilians and prevent a massacre.

Critics erroneously compare Libya today to any number of false ideals, but this is not the correct way to evaluate the success or failure of the intervention. To do that, we should compare Libya today to what Libya would have looked like if we hadn’t intervened. By that standard, the Libya intervention was successful: The country is better off today than it would have been had the international community allowed dictator Muammar Qaddafi to continue his rampage across the country.

Critics further assert that the intervention caused, created, or somehow led to civil war. In fact, the civil war had already started before the intervention began. As for today’s chaos, violence, and general instability, these are more plausibly tied not to the original intervention but to the international community’s failures after intervention. [Continue reading…]

As long as there is no real democracy in the Middle East, ISIS will continue to mutate

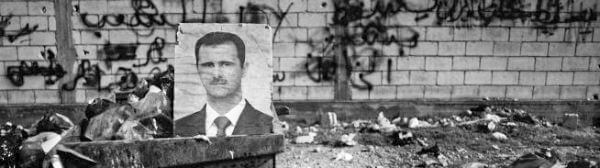

David Hearst writes: The betting is that neither the pro-Assad coalition nor the Saudi-backed one will prevail in Syria. The likeliest outcome of a ceasefire is a Syria permanently fragmented into sectarian statelets in the way Iraq was after the US invasion.

This could be regarded as the least worst option for foreign powers meddling in Syria. Jordan, the Emirates and Egypt will have stopped this dangerous thing called regime change. Saudi will have stopped Iran and Hezbollah. Russia will have its naval base and retain a foothold in the Middle East. Assad will survive in a shrunken sectarian state. The Kurds will have their enclave in the north. America will walk away once more from the region.

There is just one loser in all this – Syria itself. Five million Syrians will become permanent exiles. Justice, self-determination, liberation from autocracy will be kicked into the long grass.

The history of the region has lessons for foreign powers. It proves that fragmentation only leads to further chaos. The region needs reconciliation, common projects and stability as never before. That will not come from creating sectarian enclaves backed by foreign powers.

The Islamic State is a distraction from the real struggle of the region, which is liberation from dictatorship and the birth of real democratic movements. IS is not a justification for the strong men. It is a product of their resistance to change. History did not start in 2011 and it won’t stop now. The revolutions of 2011 were empowered by decades of misrule. There is a reason why millions of Arab rose – peacefully at first – against their rulers and that reason still exists today.

As long as there is no real democratic solution in the Middle East, the Islamic State group will continue to mutate like a pathogen that has become antibiotic-resistant in the body politic of the Middle East. Each time it changes shape, it will become more virulent. [Continue reading…]

Why it’s wrong to say that the Arab uprisings failed

Marc Lynch writes: Conventional wisdom holds that the Arab uprisings that began in Tunisia in December 2010 failed. It’s hard to argue with such a harsh verdict. Most Arab regimes managed to survive their popular challenges through some combination of cooptation, coercion and modest reform. Egypt’s transition ended in an even harsher military regime. Yemen and Libya collapsed into state failure and regionalized wars, while Syria degenerated into a horrific war.

But simply dismissing the uprisings as a failure does not capture how fully they have transformed every dimension of the region’s politics. Today’s authoritarians are more repressive because they are less stable, more frightened and ever more incapable of sustaining their domination. With oil prices collapsing and popular discontent again spiking, it is obvious that the generational challenge of the Arab uprising is continuing to unfold. “Success or failure” is not a helpful way to understand these ongoing societal and political processes.

Instead of binary outcomes, political scientists have begun to more closely examine the new political forms and patterns, which the uprisings generated. A few months ago, the Project on Middle East Political Science convened a virtual symposium with 30 political scientists examining how the turmoil of the past five years have affected Arab politics. Those essays, many of them originally published on the Monkey Cage, are now available for open access download as an issue of POMEPS Studies. Those essays offer an ambivalent, nuanced perspective on what has and has not changed in the region since 2011 – and point to the many challenges to come.

The new politics shaped by the Arab uprising can be tracked along multiple levels of analysis, including regional international relations, regimes, states, and ideas. [Continue reading…]

The painful lessons of Brussels seem hard to learn, so they continue

Rami G Khouri writes: The terror attacks in Brussels this week, beyond their inherent cruelty and criminality, in themselves are not particularly distinctive or noteworthy in the larger picture of Islamic State and other acts of terrorism, which have become common fare in this era of expanding violence across all continents. Terrorism database compilers are working overtime these months trying to take note of every such act — and that may be the real significance of what is going on these days: hundreds of thousands of desperate and dehumanized individuals transform their former local grumblings or security-forced passivity into a growing global network of terrorists and anarchists whose numbers are beyond the capacity of any intelligence system’s ability to monitor, arrest, prevent, or shut down.

The heart of this criminal universe mainly comprises Arabs or emigrants of Arab descent. The terror problem at its deepest core is the consequence of the dysfunction of mostly Arab societies that have been subjected to more than half a century of security-enforced docility and lack of citizen rights. Nearly 400 million human beings today across the Arab world were born with innate natural and human rights to freedom, identity, growth, and societal well-being, but they have not been allowed to manifest these dimensions of their full humanity.

Economic, political, environmental, and social constraints that have grown more severe in recent decades have sparked a terrible cycle of stagnation and de-development in the minds and capabilities of men and women — while shopping malls, water-pipe cafes, reality television, supermarkets, and cell phone shops have proliferated like mad across the Arab world, in a futile attempt to keep people busy and happy with material diversions. [Continue reading…]

The war on terror has turned the whole world into a battlefield

Arun Kundnani writes: When opinion polls find that most Muslims think Westerners are selfish, immoral and violent, we have no idea of the real causes. And so we assume such opinions must be an expression of their culture rather than our politics.

Donald Trump and Ted Cruz have exploited these reactions with their appeals to Islamophobia. But most liberals also assume that religious extremism is the root cause of terrorism. President Obama, for example, has spoken of “a violent, radical, fanatical, nihilistic interpretation of Islam by a faction — a tiny faction — within the Muslim community that is our enemy, and that has to be defeated.”

Based on this assumption, think-tanks, intelligence agencies and academic departments linked to the national security apparatus have spent millions of dollars since 9/11 conducting research on radicalization. They hoped to find a correlation between having extremist religious ideas, however defined, and involvement in terrorism.

In fact, no such correlation exists, as empirical evidence demonstrates — witness the European Islamic State volunteers who arrive in Syria with copies of “Islam for Dummies” or the alleged leader of the November 2015 Paris attacks, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who was reported to have drunk whisky and smoked cannabis. But this has not stopped national security agencies, such as the FBI, from using radicalization models that assume devout religious beliefs are an indicator of potential terrorism.

The process of radicalization is easily understood if we imagine how we would respond to a foreign government dropping 22,000 bombs on us. Large numbers of patriots would be volunteering to fight the perpetrators. And nationalist and religious ideologies would compete with each other to lead that movement and give its adherents a sense of purpose.

Similarly, the Islamic State does not primarily recruit through theological arguments but through a militarized identity politics. It says there is a global war between the West and Islam, a heroic struggle, with truth and justice on one side and lies, depravity and corruption on the other. It shows images of innocents victimized and battles gloriously waged. In other words, it recruits in the same way that any other armed group recruits, including the U.S. military.

That means that when we also deploy our own militarized identity politics to narrate our response to terrorism, we inadvertently reinforce the Islamic State’s message to its potential recruits. When British Prime Minister David Cameron talks about a “generational struggle” between Western values and Islamic extremism, he is assisting the militants’ own propaganda. When French President François Hollande talks of “a war which will be pitiless,” he is doing the same.

What is distinctive about the Islamic State’s message is that it also offers a utopian and apocalyptic vision of an alternative society in the making. The reality of that alternative is, of course, oppression of women, enslavement of minorities and hatred of freedom.

But the message works, to some extent, because it claims to be an answer to real problems of poverty, authoritarian regimes and Western aggression. Significantly, it thrives in environments where other radical alternatives to a discredited status quo have been suppressed by government repression. What’s corrupting the Islamic State’s volunteers is not ideology but by the end of ideology: they have grown up in an era with no alternatives to capitalist globalization. The organization has gained support, in part, because the Arab revolutions of 2011 were defeated, in many cases by regimes allied with and funded by the U.S.

After 14 years of the “war on terror,” we are no closer to achieving peace. The fault does not lie with any one administration but with the assumption that war can defeat terrorism. The lesson of the Islamic State is that war creates terrorism. [Continue reading…]

Syria’s war: Five years of horror

Explained: How the Arab Spring led to an increasingly vicious civil war in Yemen

By Sophia Dingli, University of Hull

A missile strike on a crowded market in the northern Yemeni province of Hajja has killed dozens of civilians and injured many others. It comes almost a year after a coup by Houthi “nationalists” and the start of a Saudi-led bombing campaign, ostensibly on behalf of the Yemeni government – a devastating war that shows no signs of dissipating.

Since the bombing began in March 2015, there have been at least 3,000 civilian casualties, among them 700 children and a further 26,000 have been injured. Some 3.4m children are out of school, while 7.6m people are a step away from famine. Almost all Yemenis are in need of some form of aid.

In addition to the human casualties, 23 UNESCO heritage sites have been bombed and destroyed along with hospitals, centres for the blind, ambulances, Red Cross offices and a home for the elderly.

The war has been a brutal affair: all sides have allegedly committed war crimes. The Saudi coalition has been using banned cluster munitions manufactured in the US, while the Houthi rebels have been laying landmines. Child soldiers have been used by both the Houthis and government forces.

The world beyond the Middle East has struggled to mount an appropriate and united response to the conflict. The US and the UK have been supporting the Saudi war effort, while the EU parliament has called for an embargo on arms sales to Saudi Arabia. All attempts to form a sustainable peace building effort have been met with intransigence by the belligerents and ended in failure.

To understand why this is and to come up with some way of bringing this slaughter, misery and suffering to an end, we must revisit the root causes of the war and the factors that are still getting in the way of any sort of peace process.

Saudi activists – who are they and what do they want?

Madawi Al-Rasheed writes: Fearing a domino effect from the Arab uprisings in 2011, the Saudi regime adopted multiple strategies to stifle dissent in the kingdom.

First it started using oil wealth to distribute millions of dollars in benefits, job opportunities and other welfare services. Then followed repression, leading to hundreds of peaceful activists for change being rounded up and put in prison. Some were flogged, others executed; many still face the death penalty.

By 2014 new anti-terrorism laws and royal decrees had criminalized practically all forms of dissent, including demonstrations, civil disobedience, criticizing the king or communicating with foreign media without government authorization.

Yet these measures have failed to mute a wide range of activists.

Under stifling conditions, activism has moved to the virtual world, taking advantage of the tremendous proliferation of social media in the kingdom. [Continue reading…]

How the Syrian revolt went so horribly, tragically wrong

Liz Sly reports: From Egypt to Yemen, Libya to Bahrain, the brief flowering of freedom and hope that surged across the Middle East five years ago has failed more spectacularly than could have been imagined back when people chanting for freedom thronged the streets of towns and cities regionwide.

Syria marks the fifth anniversary of its first peaceful protest Tuesday in the shadow of a brutal war that has sucked in global powers and fueled the rise of radicals such as the Islamic State. Libya and Yemen are likewise locked in savage conflicts.

In other countries, such as Egypt, autocratic regimes have reasserted their control with a vengeance, clamping down on liberties even more fiercely than had been the case before the demonstrations were held.

In all of them, except Tunisia, the moderates who dominated the early days of the revolts have been silenced, imprisoned, hunted down or driven into exile, either by the governments that sought to repress them or the extremists who moved into the vacuum created when state authority collapsed.

Whether those early protesters were ever truly representative is in question, said Rami Nakhla, one of the most prominent leaders of the early Syrian protests, directing the Local Coordination Committees from exile in Beirut. He now lives in the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep near Syria’s border, a hub for many of the activists who have been forced to flee.

But he also wonders whether they ever stood a chance. “We are hostage to two choices: either the authoritarians or the extremist Islamists,” he said. “Should we accept this equation? That we endorse either dictatorship or Islamic extremism?”

It is a false choice, but it has served to sustain the twin tyrannies that proved the undoing of the Arab Spring, said Shadi Hamid of the Washington-based Brookings Institution. Since well before the revolts, the region’s dictators have raised the specter of Islamist extremism to scare ordinary citizens into submission and justify their harsh oppression to foreign powers. And extremists exploit the climate of fear to win recruits and justify their own brutal tactics.

“Authoritarian regimes and groups like ISIS both rely on violence and oppression to promote their political objectives,” he said, using another term for the Islamic State. “For regimes, it’s actually a successful strategy, at least in the case of Egypt and Syria. The Assad regime has been able to promote its own narrative very successfully, and many members of the international community say the armed opposition is primarily a radical opposition, that there are no moderate rebels.” [Continue reading…]

Obama’s disastrous handling of the Syrian conflict

Hisham Melhem writes: For more than three decades, I have tried to interpret America to the Arabs and to explain the Arabs to Americans. I have never seen such disillusionment with an American president and his policies expressed by people in the region, ordinary citizens as well as public figures. In private, I have heard Arab officials express critical views of Obama and his style of leadership bordering on utter contempt; some Israeli officials did that publicly. For his Arab allies, Obama was too deferential to Iran and too quick to dump President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt — views also held by Israeli officials. Arabs feel Obama also mishandled Syria, a view strongly held also by Turkey. It is rarely the case for an American president to find that his relationships with Arabs, Israelis, and Turks are simultaneously troubled and in some cases very bitter.

Nor is Obama popular with the region’s ordinary citizens. A Pew Research Center poll in June 2015 shows that Obama’s image in the Middle East is mostly negative, with more than eight in ten Palestinians and Jordanians saying that they have no confidence in Obama to do the right thing in world affairs. In Lebanon 64 percent have no confidence in Obama’s leadership, with only 50 percent of Israelis saying they have confidence in the American president. In Turkey Obama’s fortune is better, but not by much where 46 percent of Turks have a negative assessment of his leadership. There is much anecdotal evidence showing that Arab youth in general have soured on Obama, accusing him of reneging on his early pledges to oppose Arab despotism and to stand by those who sought peaceful change in Egypt and Bahrain, and of abandoning Libya after the fall of the Gadhafi regime. However, what angers many Arabs is Obama’s disastrous handling of the Syrian conflict; they blame his indecisiveness on challenging the Bashar Al-Assad regime’s predations, and halfhearted measures toward helping the Syrian opposition, for the worst human tragedy in the twenty-first century. [Continue reading…]

The Arab revolutions have been misunderstood or even wilfully mischaracterised by Western leftists

In a review of Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila al-Shami, Joe Gill writes: As well as a non-orthodox telling of the conflict from the point of view of the activists and fighters who took part in the revolution, the book also speaks to the confusion and reluctance of western progressives to engage in the reality of Syria. “What’s happening is of immense human, cultural importance, not just for Syria and the Middle East but for the whole world. We do actually live in age of very messy revolutions,” says Yassin-Kassab.

Western suspicion of Islamists of whatever hue colours how the Syrian revolution is perceived, leading to potentially disastrous conclusions as to how the war might be ended. “There are a huge range of Islamists – we don’t at all agree with them, but nevertheless they are there. Some are foreigners and criminals, some of them are Syrians and represent a constituency,” said Yassin-Kassab.

By late 2013, and certainly by 2015, a consensus had emerged in the West, if not in the Gulf and Turkey, that there were no good opposition forces left on the ground who could take the reigns if and when Assad fell.

The Arab revolutions, because they do not conform to a traditional Marxist or anti-colonial narrative of liberation struggles, and in the case of Syria and Libya are ranged against nominally “anti-imperialist” regimes, have also been misunderstood or even wilfully mischaracterised by western leftists, according to al-Shami and Yassin-Kassab. “I actually fail to see the difference between the left and right as a result of all this. You don’t hear anything about [the Syrian revolutionary movement] in western leftist circles. You need to go to the grassroots to what people are really thinking and feeling.” Without this bottom up approach, the author says that outsiders are “open to the first propagandist narrative that comes along.” [Continue reading…]

The Arab world and the West: A shared destiny

Jean-Pierre Filiu discusses his book, Les Arabes, leur destin et le nôtre, which aims to shed light on struggles in the Arab World today by exploring the entwined histories of the Arab World and the West, starting with Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt in 1798, through military expeditions and brutal colonial regimes, broken promises and diplomatic maneuvers, support for dictatorial regimes, and the discovery of oil riches. He also discusses the “Arab Enlightenment” of the 19th Century and the history of democratic struggles and social revolts in the Arab world, often repressed.

Filiu is also the author of From Deep State to Islamic State: The Arab Counter-Revolution and its Jihadi Legacy, “an invaluable contribution to understanding the murky world of the Arab security regimes.”

Fight ISIS with democracy

Rached Ghannouchi, co-founder and president of Tunisia’s Muslim democrats party, Ennahdha, writes: As more countries confront the question of how to counter terrorist groups like ISIS, it is clear that a short-term, reductionist approach focused largely on military force has proven ineffective. Efforts to dislodge the so-called Islamic State through bombing, and to keep it at bay by strengthening and equipping security forces in the places it operates, have so far had limited success despite their enormous financial costs.

This is because, although such efforts are critical, they are not sufficient. The rise of ISIS, and its ability to recruit from a region that just five years ago was swept by democratic hopes and aspirations, requires a global response that is informed by where the group came from. For such a response to work, I believe it must reflect five principles. These are based on Tunisia’s experience as the most successful democratic transition to emerge from the Arab uprisings, as well as my personal intellectual and political work in Tunisia and the Arab world over five decades.

First, there is no universal approach to tackling ISIS. Rather, the group can only be defeated through a variety of locally designed and targeted responses. Extremist groups like ISIS use technology and social networks to cross boundaries and attract recruits globally—but their discourse is linked to local grievances wherever they operate. [Continue reading…]

The failure of Egypt’s democratic transition was not inevitable

Michael Wahid Hanna writes: The fifth anniversary of the 2011 Egyptian uprising has produced an oddly structuralist set of reflections in which the failure of its democratic transition has taken on an almost foreordained quality. Influential political science interpretations of the Egyptian uprising’s failure have focused analytical attention on structural factors, such as the role of a politicized and overreaching military, the uneven balance of power between the Muslim Brotherhood and its non-Islamist competitors, the former regime’s political structure and the weakness of transitional institutions.

Structure matters, of course. But so does agency. Overly structural interpretations miss the decisive impact of highly contingent events, deflects responsibility from the political actors whose choices drove the transition off course and can lead to unwarranted skepticism about the possibility of meaningful political change.

Egypt’s transition to a legitimate, civilian-led political order after the popular mobilization of January 2011 always faced long odds, but the failure of the transition was never inevitable. Structural explanations of the July 2013 military coup gloss over the fear and uncertainty that shaped political decision-making over the previous two years. The political openings of 2011 were real and potentially transformative and could have provided a platform for slow but sustainable change. Structural analysis should not become an excuse for political malpractice or an analytical surrender to the necessity of autocracy. Different decisions by key political actors such as the military, the Muslim Brotherhood and the National Salvation Front could have shaped a very different political environment. [Continue reading…]

Violence of young men diminishes when they have jobs and families

The Economist reports: In August 2014 Boko Haram fighters surged through Madagali, an area in north-east Nigeria. They butchered, burned and stole. They closed schools, because Western education is sinful, and carried off young girls, because holy warriors need wives.

Taru Daniel escaped with his father and ten siblings. His sister was not so lucky: the jihadis kidnapped her and took her to their forest hideout. “Maybe they forced her to marry,” Mr Daniel speculates. Or maybe they killed her; he does not know.

He is 23 and wears a roughed-up white T-shirt and woollen hat, despite the blistering heat in Yola, the town to which he fled. He has struggled to find a job, a big handicap in a culture where a man is not considered an adult unless he can support a family. “If you don’t have money you cannot marry,” he explains. Asked why other young men join Boko Haram, he says: “Food no dey. [There is no food.] Clothes no dey. We have nothing. That is why they join. For some small, small money. For a wife.”

Some terrorists are born rich. Some have good jobs. Most are probably sincere in their desire to build a caliphate or a socialist paradise. But material factors clearly play a role in fostering violence. North-east Nigeria, where Boko Haram operates, is largely Islamic, but it is also poor, despite Nigeria’s oil wealth, and corruptly governed. It has lots of young men, many of them living hand to mouth. It is also polygamous: 40% of married women share a husband. Rich old men have multiple spouses; poor young men are left single, sex-starved and without a stable family life. Small wonder some are tempted to join Boko Haram.

Globally, the people who fight in wars or commit violent crimes are nearly all young men. Henrik Urdal of the Harvard Kennedy School looked at civil wars and insurgencies around the world between 1950 and 2000, controlling for such things as how rich, democratic or recently violent countries were, and found that a “youth bulge” made them more strife-prone. When 15-24-year-olds made up more than 35% of the adult population — as is common in developing countries — the risk of conflict was 150% higher than with a rich-country age profile.

If young men are jobless or broke, they make cheap recruits for rebel armies. And if their rulers are crooked or cruel, they will have cause to rebel. Youth unemployment in Arab states is twice the global norm. The autocrats who were toppled in the Arab Spring were all well past pension age, had been in charge for decades and presided over kleptocracies. [Continue reading…]