The Wall Street Journal reports: Victory comes at a cost.

Since entering the Syrian war last year, Russia successfully ended America’s status as the Middle East’s sole superpower, an achievement capped by the fall of Aleppo.

That rise has turned Moscow into the region’s indispensable power broker. In Europe, too, the migrant wave unleashed by the Syrian war strengthened Moscow’s sway, fueling populist parties friendly to President Vladimir Putin.

The assassination of Russia’s ambassador to Turkey on Monday, however, highlighted the flip side of this dizzying rise. As America’s influence has shrunk, Russia has taken the place the U.S. long occupied in the minds of many people in the Middle East: an alien imperialist power seen as waging war on Muslims and Islam.

There haven’t been any recent anti-American protests in the region. But amid the agony of Aleppo, tens of thousands of protesters converged this month outside Russian missions from Istanbul to Beirut to Kuwait City—where the chanting, led by local lawmakers, was clear: “Russia is the enemy of Islam.”

The Turkish policeman who gunned down Ambassador Andrey Karlov on Monday shouted that he was avenging the suffering of Aleppo, which had been subjected to a year of Russian bombing before the Syrian regime and its Shiite allies conquered the rebel-held parts of the city in recent weeks.

The diplomat’s assassination, while condemned by governments, was greeted with open joy on Arabic social media, and in Palestinian refugee camps.

“Russia is certainly being perceived as the new bully in the neighborhood,” said Hassan Hassan, a fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy in Washington. “The way people react to its involvement in the decimation of one of the most revered Sunni cities in the Middle East, Aleppo, is reminiscent of how the U.S. was viewed after its occupation of Iraq. You only need to follow how the killer of the Russian ambassador was glorified throughout the region to get an idea of how Russia is despised by the populace today.” [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: imperialism

The strange sympathy of the Far Left for Putin

Gershom Gorenberg writes: Jeremy Corbyn, the grim, controversial, and recently re-elected leader of Britain’s Labour Party, rejects the idea of protesting outside Russia’s embassy in London against that country’s brutal bombing of Syria. “The focus on Russian atrocities or Syrian army atrocities,” said a Corbyn aide this week, distracts attention from “very large scale civilian casualties as a result of the U.S.-led coalition bombing.”

In case this is a bit obtuse, let’s go over to Britain’s Stop the War coalition, which Corbyn chaired before he was elected Labour leader. In a radio interview, current vice-chairman Chris Nineham said that protesting Russian atrocities would increase “hysteria and jingoism.” The way to end the Syria conflict, he said, was to “oppose the West.”

In another words, when we say we’re against war, we don’t mean Vladimir Putin’s war. We mean war waged by Western imperialists.

To fill in some dots: The idea of protesting outside Russian embassies, not just in London but around the world, reportedly came from Labour MP Ann Clwyd. It’s true that Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson endorsed the proposal. But ignoring Russian war crimes because Johnson opposes them is a bit like ignoring Donald Trump’s misogyny because some Republicans also object to it.

As for the equation of Russian and coalition actions, The Guardian did a fact-check with the monitoring group Airwars. The civilian death rate from Russian attacks, said the group’s director, “probably outpaces the coalition by a rate of eight to one.” The coalition tries to limit civilian deaths; the Russians deliberately target civilians, he said.

Predictably, lots of people in the riven Labour Party are outraged by Corbyn’s stance. It’s only the latest instance of Corbyn’s fossilized and one-dimensional anti-imperialism being an embarrassment for the left. In the United States, Putin’s most prominent fan is the embarrassment of the right.

Still, Corbyn has his American counterparts — starting with Green Party candidate Jill Stein. Until a few days ago, Stein had a statement on her website saying that the United States should end any military role in Syria, impose an arms embargo, and work “with Syria, Russia, and Iran to restore all of Syria to control by the government.” The “anti-war” candidate’s stance, in other words, was to let the war crimes continue until the Assad regime and its patrons massacre their way to victory. [Continue reading…]

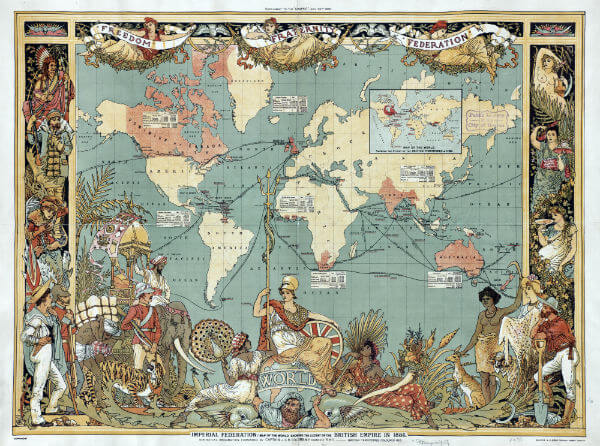

Uncovering the brutal truth about the British empire

Marc Parry writes: Help us sue the British government for torture. That was the request Caroline Elkins, a Harvard historian, received in 2008. The idea was both legally improbable and professionally risky. Improbable because the case, then being assembled by human rights lawyers in London, would attempt to hold Britain accountable for atrocities perpetrated 50 years earlier, in pre-independence Kenya. Risky because investigating those misdeeds had already earned Elkins heaps of abuse.

Elkins had come to prominence in 2005 with a book that exhumed one of the nastiest chapters of British imperial history: the suppression of Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion. Her study, Britain’s Gulag, chronicled how the British had battled this anticolonial uprising by confining some 1.5 million Kenyans to a network of detention camps and heavily patrolled villages. It was a tale of systematic violence and high-level cover-ups.

It was also an unconventional first book for a junior scholar. Elkins framed the story as a personal journey of discovery. Her prose seethed with outrage. Britain’s Gulag, titled Imperial Reckoning in the US, earned Elkins a great deal of attention and a Pulitzer prize. But the book polarised scholars. Some praised Elkins for breaking the “code of silence” that had squelched discussion of British imperial violence. Others branded her a self-aggrandising crusader whose overstated findings had relied on sloppy methods and dubious oral testimonies.

By 2008, Elkins’s job was on the line. Her case for tenure, once on the fast track, had been delayed in response to criticism of her work. To secure a permanent position, she needed to make progress on her second book. This would be an ambitious study of violence at the end of the British empire, one that would take her far beyond the controversy that had engulfed her Mau Mau work.

That’s when the phone rang, pulling her back in. A London law firm was preparing to file a reparations claim on behalf of elderly Kenyans who had been tortured in detention camps during the Mau Mau revolt. Elkins’s research had made the suit possible. Now the lawyer running the case wanted her to sign on as an expert witness. Elkins was in the top-floor study of her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when the call came. She looked at the file boxes around her. “I was supposed to be working on this next book,” she says. “Keep my head down and be an academic. Don’t go out and be on the front page of the paper.”

She said yes. She wanted to rectify injustice. And she stood behind her work. “I was kind of like a dog with a bone,” she says. “I knew I was right.”

What she didn’t know was that the lawsuit would expose a secret: a vast colonial archive that had been hidden for half a century. The files within would be a reminder to historians of just how far a government would go to sanitise its past. And the story Elkins would tell about those papers would once again plunge her into controversy. [Continue reading…]

A beleaguered Britain takes comfort in nostalgia for empire

Paul Harris writes: The British empire never lacked contradictions. A global juggernaut standing with its military boot on millions of necks, practising commercial coercion and diplomatic cynicism, it nonetheless routinely thought of itself as a plucky underdog. Its heroes were the handful of redcoats at Rorke’s Drift fighting off the Zulu masses, or General Charles Gordon of Khartoum, going down against the odds in a last stand against religious zealots in the Sudan.

British soldiers, diplomats and traders pictured themselves as almost accidental conquerors, vanquishing a quarter of the planet’s landmass in between tea, tiffin and cricket matches. They maintained a detached stiff upper lip and publicly ignored the unpleasant reality of the Maxim gun – a luxury not afforded to the locals on its business end.

Britain preferred to see its dominance of a fifth of the world’s population as some sort of benevolent, God-given mission to bring law, order and free trade to benighted corners of the world. As George Bernard Shaw complained: ‘The ordinary Britisher imagines that God is an Englishman.’

It was a powerful notion and it has not gone away. Even though the Empire is reduced to a scattering of tiny islands with names few Britons would recognise, the imperial past remains implausibly popular. Early this year, a poll showed that a full 44 per cent of Britons were proud of colonialism, far outnumbering the mere 21 per cent who regretted their country’s imperial past. The survey was not an outlier. A 2014 report showed a mere 15 per cent of Britons thought the colonised might just have been left worse off by the experience. [Continue reading…]

Untangling the complicated legacies of colonialism and failed Arab regimes overshadowing today’s conflicts in the Middle East

Rami G Khouri writes: Why have most Middle Eastern lands that Great Britain, Italy, and France managed as mandates or colonies become violent wrecks and sources of large-scale conflict and human despair? It is just as dishonest to blame mainly Western colonialism for our national wreckages and rampant instability as it is to blame only Arab people and culture for those failings. We need a more complete and integrated analysis of the multiple phenomena that shaped our last erratic century.

Initially, we must absolutely acknowledge that Arab states’ inability to achieve sustainable economic growth and pluralistic democracies is the core reason for our problems today. The main reason for this reason, however, is to be found in a more complex set of interlocking relationships among powerful political actors inside our countries and capitals far and near.

This requires going back before 1916, maybe a century or two, to recall how European powers conquered much of the world as colonies or sites of unchecked imperial plunder. The main problem with Sykes-Picot is not only what happened in and after 1916; it is also heavily a consequence of the European colonial mindset that matured in the century before 1916, and continued to exercise its colonial prerogatives for decades to follow — perhaps even in today’s continued use of European, Russian, and American military power across our region.

At the same time, three critical issues after 1916 made it virtually impossible for many Arab countries to transition from Euro-manufactured instant states born on after-dinner napkins in the hands of Cognac-mellowed British and French colonial officers, to stable, democratic, prosperous sovereign states.

These three issues were, in their historical order:

1) British support for Zionism and a Jewish state in Palestine in November 1917, which plunged Palestine into endless Zionism-Arabism warfare since then, and sucked in other Arab states, Iran, and others yet;

2) the discovery of large amounts of oil in the Middle East in the 1930s especially, which the West needed to maintain access to for its own industrial expansion; and,

3) the post-1947 Cold War between the U.S.-led West and the Russian-led Soviet Communist states that was translated into perpetual proxy wars across the Middle East for forty-four years, and maybe is resurfacing today in new guises. [Continue reading…]

Britain should stop trying to pretend that its empire was benevolent

By Alan Lester, University of Sussex

The recent debacle of David Cameron’s filmed condemnation of Nigerian and Afghan corruption and the Queen’s remark on Chinese officials’ rudeness highlights the persistence of imperial thinking in Britain. There seems to be a continuing assumption within the British establishment that it sets an example for others to follow and that the British are owed deference by others.

Ever since evangelical antislavery activists campaigned for Britain to abolish the transatlantic slave trade, Britons have assured themselves that imperial overrule is compatible with the “benign tutelage” of other races and nations. Unlike the other European empires, Britons tell themselves, theirs was an empire founded on humanitarian compassion for colonised subjects.

The argument runs like this: while the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Belgians and Germans exploited and abused, the British empire brought ideas of protection for lesser races and fostered their incremental development. With British tutelage colonised peoples could become, eventually, as competent, as knowledgeable, as “civilised” as Britain itself. These platitudes have been repeated time and again – they are still at the heart of most popular representations of the British Empire.

Even when we are encouraged to pay attention to empire’s costs as well as its benefits, these costs are imagined solely in terms of specific incidents of violence such as the Amritsar Massacre in India or the suppression of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya. Britain has excused itself from that most structural injustice of empire – the slave trade itself – by the fact that it was Britain that pioneered its abolition.

How the curse of Sykes-Picot still haunts the Middle East

Robin Wright writes: In the Middle East, few men are pilloried these days as much as Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. Sykes, a British diplomat, travelled the same turf as T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia), served in the Boer War, inherited a baronetcy, and won a Conservative seat in Parliament. He died young, at thirty-nine, during the 1919 flu epidemic. Picot was a French lawyer and diplomat who led a long but obscure life, mainly in backwater posts, until his death, in 1950. But the two men live on in the secret agreement they were assigned to draft, during the First World War, to divide the Ottoman Empire’s vast land mass into British and French spheres of influence. The Sykes-Picot Agreement launched a nine-year process — and other deals, declarations, and treaties — that created the modern Middle East states out of the Ottoman carcass. The new borders ultimately bore little resemblance to the original Sykes-Picot map, but their map is still viewed as the root cause of much that has happened ever since.

“Hundreds of thousands have been killed because of Sykes-Picot and all the problems it created,” Nawzad Hadi Mawlood, the Governor of Iraq’s Erbil Province, told me when I saw him this spring. “It changed the course of history — and nature.”

May 16th will mark the agreement’s hundredth anniversary, amid questions over whether its borders can survive the region’s current furies. “The system in place for the past one hundred years has collapsed,” Barham Salih, a former deputy prime minister of Iraq, declared at the Sulaimani Forum, in Iraqi Kurdistan, in March. “It’s not clear what new system will take its place.”

The colonial carve-up was always vulnerable. Its map ignored local identities and political preferences. Borders were determined with a ruler — arbitrarily. At a briefing for Britain’s Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, in 1915, Sykes famously explained, “I should like to draw a line from the ‘E’ in Acre to the last ‘K’ in Kirkuk.” He slid his finger across a map, spread out on a table at No. 10 Downing Street, from what is today a city on Israel’s Mediterranean coast to the northern mountains of Iraq.

“Sykes-Picot was a mistake, for sure,” Zikri Mosa, an adviser to Kurdistan’s President Masoud Barzani, told me. “It was like a forced marriage. It was doomed from the start. It was immoral, because it decided people’s future without asking them.” [Continue reading…]

The Arab world and the West: A shared destiny

Jean-Pierre Filiu discusses his book, Les Arabes, leur destin et le nôtre, which aims to shed light on struggles in the Arab World today by exploring the entwined histories of the Arab World and the West, starting with Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt in 1798, through military expeditions and brutal colonial regimes, broken promises and diplomatic maneuvers, support for dictatorial regimes, and the discovery of oil riches. He also discusses the “Arab Enlightenment” of the 19th Century and the history of democratic struggles and social revolts in the Arab world, often repressed.

Filiu is also the author of From Deep State to Islamic State: The Arab Counter-Revolution and its Jihadi Legacy, “an invaluable contribution to understanding the murky world of the Arab security regimes.”

A generation of failed politicians has trapped the West in a tawdry nightmare

Pankaj Mishra writes: Racism, a beast cornered if not tamed after much struggle, has lumbered back to civil society in the solemn guise of “reforming” Islam. Tony Blair summons us to worldwide battle on behalf of western values while embodying, with his central Asian clients, their comprehensive negation. The handful of media institutions and individuals that are not obliged to flesh out Rupert Murdoch’s tweets on Muslims seem to be struggling to remain viable in an increasingly retrogressive political culture. Even the BBC seems determined not to stray far from the Daily Mail’s editorial line.

Unsurprisingly, we witness, as Judt pointed out, “no external inputs, no new kinds of people, only the political class breeding itself”. “The old ways of mass movements, communities organised around an ideology, even religious or political ideas, trade unions and political parties to leverage public opinion into political influence” have disappeared. Indeed, the slightest reminder of this democratic past incites the technocrats of politics, business and the media into paroxysms of scorn.

Having acted recklessly to create their own reality, they have managed to trap all of us in a tawdry nightmare – a male buddy film of singular fatuousness. At the same time, reality-making has ceased to be the prerogative of the American imperium or of the French and British chumocrats, who lost their empires long ago and are still trying to find a role for themselves.

Some random fanatic, it turns out, can make their reality far more quickly, coercing the world’s oldest democracies into endless war, racial-religious hatred and paranoia. Such is the great power surrendered by the crappy generation and its epigones. The generations to come will scarcely believe it. [Continue reading…]

Middle East still rocking from First World War pacts made 100 years ago

Ian Black writes: In an idle moment between cocktail parties in the Arab capital where they served, a British and French diplomat were chatting recently about their respective countries’ legacies in the Middle East: why not commemorate them with a new rock band? And they could call it Sykes-Picot and the Balfour Declaration.

It was just a joke. These first world war agreements cooked up in London and Paris in the dying days of the Ottoman empire paved the way for new Arab nation states, the creation of Israel and the continuing plight of the Palestinians. And if their memory has faded in the west as their centenaries approach, they are still widely blamed for the problems of the region at an unusually violent and troubled time.

“This is history that the Arab peoples will never forget because they see it as directly relevant to problems they face today,” argues Oxford University’s Eugene Rogan, author of several influential works on modern Middle Eastern history.

In 2014, when Islamic State fighters broke through the desert border between Iraq and Syria – flying black flags on their captured US-made Humvees – and announced the creation of a transnational caliphate, they triumphantly pronounced the death of Sykes-Picot. That gave a half-forgotten and much-misrepresented colonial-era deal a starring role in their propaganda war – and a new lease of life on Twitter. [Continue reading…]

Spinning against imperialism: Jeremy Corbyn, Seumas Milne and the Middle East

By Brian Whitaker, al-bab, October 27, 2015

When Jeremy Corbyn became leader of the opposition Labour party in Britain last month I wrote a blog post looking at his public statements on international affairs and trying to draw some conclusions about how British policy in the Middle East might change under a Corbyn-led government.

While some of Corbyn’s ideas struck me as naive there were others that looked more promising. Along with his unwillingness to be drawn into military adventures his declared intention to place human rights “in the centre” of foreign policy seemed like a positive development.

Corbyn has since had some success in that area, embarrassing the government over its cosy relationship with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. The government has been struggling to justify its eagerness to do business with the Saudis in the face of their egregious human rights abuses and on this issue the British public, together with large sections of the media, appear to be on Corbyn’s side. This is clearly one of the government’s weak spots, ripe for Labour to exploit.

Last week brought a distraction from the business of opposing the government, however, with the appointment of Guardian columnist Seumas Milne as Executive Director of Strategy and Communications – in effect, as Corbyn’s chief spin doctor. It’s the post formerly held by Alastair Campbell in Tony Blair’s government, and it gives the holder a lot of influence if not actual power. At the very least we can expect Milne to be in daily contact with Corbyn, discussing how to present Labour’s policies and respond to events. Continue reading

Leftists who think politics is more important than people

In response to Jeremy Corbyn’s appointment of Seumas Milne as the UK Labour Party’s Executive Director of Strategy and Communications, Oliver Bullough writes: For Milne, geopolitics is more important than people. Whatever crisis strikes the world, the West’s to blame. Why did a group of psychopaths attack a magazine and a supermarket in Paris? “Without the war waged by western powers, including France, to bring to heel and reoccupy the Arab and Muslim world, last week’s attacks clearly couldn’t have taken place”.

Why did Anders Breivik slaughter 77 people? “What is most striking is how closely he mirrors the ideas and fixations of transatlantic conservatives.”

Why did two maniacs in London decapitate an off-duty soldier? “They are the predicted consequence of an avalanche of violence unleashed by the US, Britain and others.”

Milne’s geopolitics spared us having to read how the children of Beslan or the theatregoers of Moscow only had themselves to blame, but office workers in New York had no such luck. “Recognition of why people might have been driven to carry out such atrocities, sacrificing their own lives in the process – or why the United States is hated with such bitterness, not only in Arab and Muslim countries, but across the developing world – seems almost entirely absent.”

And this rampant victim blaming is not an approach confined to current affairs. His geopolitical preferences extend into history too, where he fiercely opposes any suggestion that Stalin’s Soviet Union was as bad as Hitler’s Germany. He has been caricatured as a Stalinist as a result, something that appears to irritate some of his once-and-future Guardian colleagues (he is on leave from the paper). I got into a Twitter debate with Zoe Williams yesterday, in which she pointed out: “he’s written reams about the crimes of Stalin”.

He has indeed, but he has written about them in the manner of a Brit acknowledging the Amritsar massacre, before pointing out how much worse off India would be without trains. [Continue reading…]

Anti-imperialism 2.0: Selective sympathies, dubious friends

Charles Davis writes: The new imperialism is caring a bit too much about the suffering of people who are being brutalized by a regime which is not currently an ally of the United States – and the new anti-imperialism is not giving a damn at all, solidarity that extends beyond the border permissible only if the drawing of attention to their plight could not possibly be used as ammunition by the “humanitarian” militarists of the American empire. The world, in this view, is divided into but two camps: those with America and those against it, with the good anti-imperialist’s outrage dialed up if the atrocity can be linked to the United States, as well it should be, but dialed down to total silence if it’s not.

This is, of course, the “anti-imperialism” of the reactionary, in more than one sense: How a person of the left responds to a pile of dead women and children is in effect dictated by how the U.S. government itself responds, the advocate of the poor and forgotten consigning foreigners to their fate – “not our problem, pal,” as one popular liberal congressman essentially put it on cable TV – if their interests have the misfortune of being perceived as aligned with America’s, the left’s commitment to internationalism abandoned for an inverted form of muddled nationalism that sees U.S. imperialism as not just one factor to consider in a complex world, but the only factor relevant in how we in the imperial core should view what happens on the rest of the globe. And if your cause is sullied by the perception it’s America’s cause too? The leftist sounds just like that liberal who sounds like Pat Buchanan: Sorry, pal, if you wanted our solidarity you should have been born somewhere that better lends itself to a black-and-white anti-imperial critique. [Continue reading…]

Syria exposed the selective anti-imperialism of the anti-war movement

Mark Boothroyd writes: The Syrian revolt against the Assad regime is now in its fifth year, the death toll from the conflict has surpassed 330,000 with over 1 million wounded, 215,000 are still detained in regime prisons, 200,000 are missing, and between 650,000 and 1,000,000 people are under starvation siege by the regime in rebel towns and cities. Bombings of civilian areas by the regime are a daily occurrence, 4.5 million Syrians are refugees, and 8 million, almost half the remaining population, are internally displaced.

In all this time there was no direct western intervention in Syria against Assad. No bombs were dropped on Syria by Western powers until mid-2014, the fourth year of the revolution, and these were targeted at ISIS, not the regime. Not a single bomb has been dropped on regime military installations by the Coalition air force.

All the hype and warnings notwithstanding, Western aid to the rebels has been very limited. By mid-2013 the Free Syrian Army had received only $12 million of a promised $60 million of aid from the US , and been denied access to weaponry by the EU. The aid they did receive was only non-lethal aid consisting of food, medicine and vehicles. From 2012 onwards the CIA was involved in monitoring weapons shipments to Syria; its role was to stop them receiving the anti-air missiles and heavy weaponry that could have neutralised Assad’s airforce and armour and hastened the downfall of the regime.

When the US did finally begin to arm and train rebels in 2014, it was tightly controlled to a ridiculous extent. In contrast the regime has $3.5 billion worth of contracts for arms from Russia, and loans to pay for it. With Syria’s domestic weapons industry too small to produce enough arms to sustain a protracted conflict, the imperialist intervention which has kept the conflict going and maintains it to this day is from Russia.

The revolutions exposed that for many in the anti-war movement, opposition to imperialist intervention only extended to opposition to imperialist intervention by the UK, US, EU, and their allies. There was no opposition to the imperialist actions of the Russian government, or the crucial support given by the Iranian government to the Assad regime. [Continue reading…]

European imperialism grew out of a hunger for pepper

Stephen Kinzer writes: As Europe began awakening into the modern age, people were eager for new sensations. The arrival of exotic spices dazzled them. Pepper is the reason modern imperialism was invented.

For generations after their founding in the early 17th century, two powerful mercantile forces dominated much of the world: the East India Company, based in London, and the Dutch East India Company, based in Amsterdam. They were richer and had greater reach than any government — complete with armies, navies, merchant fleets, fortified ports, plantations, court systems, prisons, currencies, and treaty-making rights. With this authority, granted by the British and Dutch governments, they captured far-flung territories and sowed seeds of conflict in vast areas east of Suez.

Both of these companies were founded to bring pepper to Europe. The first islands they subdued, the Moluccas, are now part of Indonesia but were long known in the West as the Spice Islands. It is a wonderful example of how food can become the lens through which we see foreign lands. Europeans went mad for pepper and other spices. That meant ships had to be sent halfway around the world to claim land and suppress unruly natives. [Continue reading…]

The East India Company: The original corporate raiders

William Dalrymple writes: One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: “loot”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late 18th century, when it suddenly became a common term across Britain. To understand how and why it took root and flourished in so distant a landscape, one need only visit Powis Castle.

The last hereditary Welsh prince, Owain Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, built Powis castle as a craggy fort in the 13th century; the estate was his reward for abandoning Wales to the rule of the English monarchy. But its most spectacular treasures date from a much later period of English conquest and appropriation: Powis is simply awash with loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder, extracted by the East India Company in the 18th century.

There are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display at any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi. The riches include hookahs of burnished gold inlaid with empurpled ebony; superbly inscribed spinels and jewelled daggers; gleaming rubies the colour of pigeon’s blood and scatterings of lizard-green emeralds. There are talwars set with yellow topaz, ornaments of jade and ivory; silken hangings, statues of Hindu gods and coats of elephant armour.

Such is the dazzle of these treasures that, as a visitor last summer, I nearly missed the huge framed canvas that explains how they came to be here. The picture hangs in the shadows at the top of a dark, oak-panelled staircase. It is not a masterpiece, but it does repay close study. An effete Indian prince, wearing cloth of gold, sits high on his throne under a silken canopy. On his left stand scimitar and spear carrying officers from his own army; to his right, a group of powdered and periwigged Georgian gentlemen. The prince is eagerly thrusting a scroll into the hands of a statesmanlike, slightly overweight Englishman in a red frock coat.

The painting shows a scene from August 1765, when the young Mughal emperor Shah Alam, exiled from Delhi and defeated by East India Company troops, was forced into what we would now call an act of involuntary privatisation. The scroll is an order to dismiss his own Mughal revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, and replace them with a set of English traders appointed by Robert Clive – the new governor of Bengal – and the directors of the EIC, who the document describes as “the high and mighty, the noblest of exalted nobles, the chief of illustrious warriors, our faithful servants and sincere well-wishers, worthy of our royal favours, the English Company”. The collecting of Mughal taxes was henceforth subcontracted to a powerful multinational corporation – whose revenue-collecting operations were protected by its own private army.

It was at this moment that the East India Company (EIC) ceased to be a conventional corporation, trading and silks and spices, and became something much more unusual. Within a few years, 250 company clerks backed by the military force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers had become the effective rulers of Bengal. An international corporation was transforming itself into an aggressive colonial power. [Continue reading…]

A new kind of imperialism from China

Llewellyn King writes: In history, countries have sought to increase their territory by bribery, chicanery, coercion and outright force of arms. But while many have sought to dominate the seas, from the Greek city states to the mighty British Empire, none has ever, in effect, tried to take over an ocean or a sea as its own.

But that is what China is actively doing in the ocean south of the mainland: the South China Sea. Bit by bit, it is establishing hegemony over this most important sea where the littoral states — China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam — have territorial claims.

The importance of the South China Sea is hard to overestimate. Some of the most vital international sea lanes traverse it; it is one of the great fishing areas; and the ocean bed, near land, has large reserves of oil and gas. No wonder everyone wants a piece of it — and China wants all of it.

Historically China has laid claim to a majority of the sea and adheres to a map or line — known as the nine-dash map, the U-shape line or the nine-dotted line — that cedes most of the ocean area and all of the island land to it. The nine-dash map is a provocation at best and a blueprint for annexation at worst. [Continue reading…]

Do you support or oppose imperialism?

If you're against imperialism, you really should support these guys #March4Ukraine pic.twitter.com/xGPzxbKDJe

— Carl Gardner (@carlgardner) March 16, 2014