Daniel Kahneman writes: We are prone to think that the world is more regular and predictable than it really is, because our memory automatically and continuously maintains a story about what is going on, and because the rules of memory tend to make that story as coherent as possible and to suppress alternatives. Fast thinking is not prone to doubt.

The confidence we experience as we make a judgment is not a reasoned evaluation of the probability that it is right. Confidence is a feeling, one determined mostly by the coherence of the story and by the ease with which it comes to mind, even when the evidence for the story is sparse and unreliable. The bias toward coherence favors overconfidence. An individual who expresses high confidence probably has a good story, which may or may not be true…

When a compelling impression of a particular event clashes with general knowledge, the impression commonly prevails… The confidence you will experience in your future judgments will not be diminished by what you just read, even if you believe every word.

I first visited a Wall Street firm in 1984. I was there with my longtime collaborator Amos Tversky, who died in 1996, and our friend Richard Thaler, now a guru of behavioral economics. Our host, a senior investment manager, had invited us to discuss the role of judgment biases in investing. I knew so little about finance at the time that I had no idea what to ask him, but I remember one exchange. “When you sell a stock,” I asked him, “who buys it?” He answered with a wave in the vague direction of the window, indicating that he expected the buyer to be someone else very much like him. That was odd: because most buyers and sellers know that they have the same information as one another, what made one person buy and the other sell? Buyers think the price is too low and likely to rise; sellers think the price is high and likely to drop. The puzzle is why buyers and sellers alike think that the current price is wrong.

Most people in the investment business have read Burton Malkiel’s wonderful book “A Random Walk Down Wall Street.” Malkiel’s central idea is that a stock’s price incorporates all the available knowledge about the value of the company and the best predictions about the future of the stock. If some people believe that the price of a stock will be higher tomorrow, they will buy more of it today. This, in turn, will cause its price to rise. If all assets in a market are correctly priced, no one can expect either to gain or to lose by trading.

We now know, however, that the theory is not quite right. Many individual investors lose consistently by trading, an achievement that a dart-throwing chimp could not match. The first demonstration of this startling conclusion was put forward by Terry Odean, a former student of mine who is now a finance professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Odean analyzed the trading records of 10,000 brokerage accounts of individual investors over a seven-year period, allowing him to identify all instances in which an investor sold one stock and soon afterward bought another stock. By these actions the investor revealed that he (most of the investors were men) had a definite idea about the future of two stocks: he expected the stock that he bought to do better than the one he sold.

To determine whether those appraisals were well founded, Odean compared the returns of the two stocks over the following year. The results were unequivocally bad. On average, the shares investors sold did better than those they bought, by a very substantial margin: 3.3 percentage points per year, in addition to the significant costs of executing the trades. Some individuals did much better, others did much worse, but the large majority of individual investors would have done better by taking a nap rather than by acting on their ideas. In a paper titled “Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth,” Odean and his colleague Brad Barber showed that, on average, the most active traders had the poorest results, while those who traded the least earned the highest returns. In another paper, “Boys Will Be Boys,” they reported that men act on their useless ideas significantly more often than women do, and that as a result women achieve better investment results than men.

Of course, there is always someone on the other side of a transaction; in general, it’s a financial institution or professional investor, ready to take advantage of the mistakes that individual traders make. Further research by Barber and Odean has shed light on these mistakes. Individual investors like to lock in their gains; they sell “winners,” stocks whose prices have gone up, and they hang on to their losers. Unfortunately for them, in the short run going forward recent winners tend to do better than recent losers, so individuals sell the wrong stocks. They also buy the wrong stocks. Individual investors predictably flock to stocks in companies that are in the news. Professional investors are more selective in responding to news. These findings provide some justification for the label of “smart money” that finance professionals apply to themselves.

Although professionals are able to extract a considerable amount of wealth from amateurs, few stock pickers, if any, have the skill needed to beat the market consistently, year after year. The diagnostic for the existence of any skill is the consistency of individual differences in achievement. The logic is simple: if individual differences in any one year are due entirely to luck, the ranking of investors and funds will vary erratically and the year-to-year correlation will be zero. Where there is skill, however, the rankings will be more stable. The persistence of individual differences is the measure by which we confirm the existence of skill among golfers, orthodontists or speedy toll collectors on the turnpike.

Mutual funds are run by highly experienced and hard-working professionals who buy and sell stocks to achieve the best possible results for their clients. Nevertheless, the evidence from more than 50 years of research is conclusive: for a large majority of fund managers, the selection of stocks is more like rolling dice than like playing poker. At least two out of every three mutual funds underperform the overall market in any given year.

More important, the year-to-year correlation among the outcomes of mutual funds is very small, barely different from zero. The funds that were successful in any given year were mostly lucky; they had a good roll of the dice. There is general agreement among researchers that this is true for nearly all stock pickers, whether they know it or not — and most do not. The subjective experience of traders is that they are making sensible, educated guesses in a situation of great uncertainty. In highly efficient markets, however, educated guesses are not more accurate than blind guesses.

Daniel Kahneman is emeritus professor of psychology and of public affairs at Princeton University and a winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics. This article is adapted from his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” out this month from Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Category Archives: inequality

The politics of austerity

Thomas B. Edsall writes: The conservative agenda, in a climate of scarcity, racializes policy making, calling for deep cuts in programs for the poor. The beneficiaries of these programs are disproportionately black and Hispanic. In 2009, according to census data, 50.9 percent of black households, 53.3 percent of Hispanic households and 20.5 percent of white households received some form of means-tested government assistance, including food stamps, Medicaid and public housing.

Less obviously, but just as racially charged, is the assault on public employees. “We can no longer live in a society where the public employees are the haves and taxpayers who foot the bills are the have-nots,” declared Scott Walker, the governor of Wisconsin.

For black Americans, government employment is a crucial means of upward mobility. The federal work force is 18.6 percent African-American, compared with 10.9 percent in the private sector. The percentages of African-Americans are highest in just those agencies that are most actively targeted for cuts by Republicans: the Department of Housing and Urban Development, 38.3 percent; the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 42.4 percent; and the Education Department, 36.6 percent.

The politics of austerity are inherently favorable to conservatives and inhospitable to liberals. Congressional trench warfare rewards those most willing to risk all. Republicans demonstrated this in last summer’s debt ceiling fight, deploying the threat of a default on Treasury obligations to force spending cuts.

Conservatives are more willing to inflict harm on adversaries and more readily see conflicts in zero-sum terms — the basic framework of the contemporary debate. Once austerity dominates the agenda, the only question is where the ax falls.

The Robin Hood tax — turning a global crisis into a global opportunity

Learn more about the Robin Hood tax.

Robin Hood tax backed by more than 1,000 economists. (Telegraph)

Bill Gates backs Robin Hood tax on bank trades. (Guardian)

IMF report [PDF] says: “In principle, an FTT is no more difficult and, in some respects easier, to administer than other taxes.”

Inequality in America is even worse than you thought

Justin Elliot reports: There has been no shortage of headlines this week about the growing income and wealth inequality in the United States. A new study from the Congressional Budget Office, for example, found that income of the top 1 percent of households increased by 275 percent in the 30-year period ending in 2007. American households at the bottom and in the middle, meanwhile, saw income growth of just 18 to 40 percent over the same period

But less attention has been paid to the fact that not only are the numbers bad in America, they’re particularly bad when compared to other developed nations.

A new report (.pdf) by the Bertelsmann Foundation drives this point home. The German think tank used a set of policy analyses to create a Social Justice Index of 31 developed nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The United States came in a dismal 27th in the rankings.

Glenn Greenwald on two-tiered U.S. justice system, Obama’s assassination program & the Arab Spring

Ending the 30-year stranglehold on the human imagination

David Graeber writes: It’s becoming increasingly obvious that the real priority of those running the world for the last few decades has not been creating a viable form of capitalism, but rather, convincing us all that the current form of capitalism is the only conceivable economic system, so its flaws are irrelevant. As a result, we’re all sitting around dumbfounded as the whole apparatus falls apart.

What we’ve learned now is that the economic crisis of the 1970s never really went away. It was fobbed off by cheap credit at home and massive plunder abroad – the latter, in the name of the “third world debt crisis”. But the global south fought back. The “alter-globalisation movement“, was in the end, successful: the IMF has been driven out of East Asia and Latin America, just as it is now being driven from the Middle East. As a result, the debt crisis has come home to Europe and North America, replete with the exact same approach: declare a financial crisis, appoint supposedly neutral technocrats to manage it, and then engage in an orgy of plunder in the name of “austerity”.

The form of resistance that has emerged looks remarkably similar to the old global justice movement, too: we see the rejection of old-fashioned party politics, the same embrace of radical diversity, the same emphasis on inventing new forms of democracy from below. What’s different is largely the target: where in 2000, it was directed at the power of unprecedented new planetary bureaucracies (the WTO, IMF, World Bank, Nafta), institutions with no democratic accountability, which existed only to serve the interests of transnational capital; now, it is at the entire political classes of countries like Greece, Spain and, now, the US – for exactly the same reason. This is why protesters are often hesitant even to issue formal demands, since that might imply recognising the legitimacy of the politicians against whom they are ranged.

When the history is finally written, though, it’s likely all of this tumult – beginning with the Arab Spring – will be remembered as the opening salvo in a wave of negotiations over the dissolution of the American Empire. Thirty years of relentless prioritising of propaganda over substance, and snuffing out anything that might look like a political basis for opposition, might make the prospects for the young protesters look bleak; and it’s clear that the rich are determined to seize as large a share of the spoils as remain, tossing a whole generation of young people to the wolves in order to do so. But history is not on their side.

We might do well to consider the collapse of the European colonial empires. It certainly did not lead to the rich successfully grabbing all the cookies, but to the creation of the modern welfare state. We don’t know precisely what will come out of this round. But if the occupiers finally manage to break the 30-year stranglehold that has been placed on the human imagination, as in those first weeks after September 2008, everything will once again be on the table – and the occupiers of Wall Street and other cities around the US will have done us the greatest favour anyone possibly can.

Global day of rage: Hundreds of thousands march against inequity, big banks as occupy movement grows

From Buenos Aires to Toronto, Kuala Lumpur to London, hundreds of thousands of people rallied on Saturday in a global day of action against corporate greed and budget cutbacks, demanding better living conditions and a more equitable distribution of wealth and resources. Protests reportedly took place in 1,500 cities, including 100 cities in the United States — all in solidarity with the Occupy Wall Street movement that launched one month ago in New York City.

Charting inequality in America

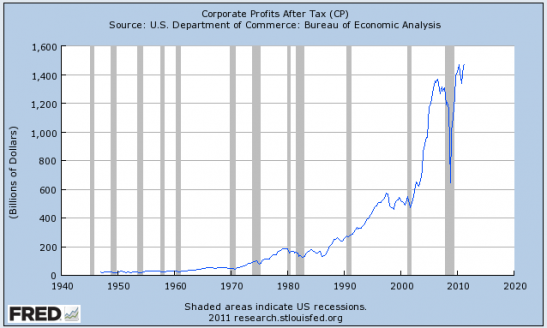

Henry Blodget writes: Inequality in this country has hit a level that has been seen only once in the nation’s history, and unemployment has reached a level that has been seen only once since the Great Depression. And, at the same time, corporate profits are at a record high.

In other words, in the never-ending tug-of-war between “labor” and “capital,” there has rarely—if ever—been a time when “capital” was so clearly winning.

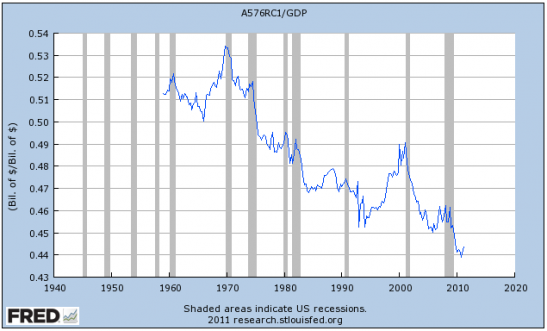

Wages as a percent of the US economy are the lowest they have ever been.

Corporate profits are at an all-time high

See 30 more charts tracking inequality in the United States.

Rebelling against the globalization of corruption

The New York Times reports:

Hundreds of thousands of disillusioned Indians cheer a rural activist on a hunger strike. Israel reels before the largest street demonstrations in its history. Enraged young people in Spain and Greece take over public squares across their countries.

Their complaints range from corruption to lack of affordable housing and joblessness, common grievances the world over. But from South Asia to the heartland of Europe and now even to Wall Street, these protesters share something else: wariness, even contempt, toward traditional politicians and the democratic political process they preside over.

They are taking to the streets, in part, because they have little faith in the ballot box.

“Our parents are grateful because they’re voting,” said Marta Solanas, 27, referring to older Spaniards’ decades spent under the Franco dictatorship. “We’re the first generation to say that voting is worthless.”

Economics have been one driving force, with growing income inequality, high unemployment and recession-driven cuts in social spending breeding widespread malaise. Alienation runs especially deep in Europe, with boycotts and strikes that, in London and Athens, erupted into violence.

But even in India and Israel, where growth remains robust, protesters say they so distrust their country’s political class and its pandering to established interest groups that they feel only an assault on the system itself can bring about real change.

Young Israeli organizers repeatedly turned out gigantic crowds insisting that their political leaders, regardless of party, had been so thoroughly captured by security concerns, ultra-Orthodox groups and other special interests that they could no longer respond to the country’s middle class.

In the world’s largest democracy, Anna Hazare, an activist, starved himself publicly for 12 days until the Indian Parliament capitulated to some of his central demands on a proposed anticorruption measure to hold public officials accountable. “We elect the people’s representatives so they can solve our problems,” said Sarita Singh, 25, among the thousands who gathered each day at Ramlila Maidan, where monsoon rains turned the grounds to mud but protesters waved Indian flags and sang patriotic songs.

“But that is not actually happening. Corruption is ruling our country.”

Increasingly, citizens of all ages, but particularly the young, are rejecting conventional structures like parties and trade unions in favor of a less hierarchical, more participatory system modeled in many ways on the culture of the Web.

In that sense, the protest movements in democracies are not altogether unlike those that have rocked authoritarian governments this year, toppling longtime leaders in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya.

Tunisia is leading the way on women’s rights in the Middle East

Brian Whitaker writes:

Last December, Tunisians rose up against their dictator, triggering a political earthquake that has sent shockwaves through most of the Middle East and north Africa. Now, Tunisia is leading the way once again – this time on the vexed issue of gender equality.

It has become the first country in the region to withdraw all its specific reservations regarding Cedaw – the international convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women.

This may sound a rather obscure and technical matter but it’s actually a very important step. It reverses a long-standing abuse of human rights treaties – especially in the Middle East – where repressive regimes sign up to these treaties for purposes of international respectability but then excuse themselves from some or all of their obligations.

Saudi Arabia, for example, operates the world’s most blatant and institutionalised system of discrimination against women – and yet, along with 17 other Arab states, it is also a party to Cedaw. It attempts to reconcile this position through reservations saying it does not consider itself bound by any part of the treaty which conflicts “with the norms of Islamic law”.

In effect, the Saudi government claims the right to ignore any part of Cedaw it doesn’t like. The “norms of Islamic law” is a meaningless phrase because the Sharia has never been formally codified. There are various methods of interpreting it and scholars often disagree in their interpretations. The “norms of Islamic law” thus means whatever the Saudis choose it to mean.

Revolt without revolution

Slavoj Žižek writes:

Repetition, according to Hegel, plays a crucial role in history: when something happens just once, it may be dismissed as an accident, something that might have been avoided if the situation had been handled differently; but when the same event repeats itself, it is a sign that a deeper historical process is unfolding. When Napoleon lost at Leipzig in 1813, it looked like bad luck; when he lost again at Waterloo, it was clear that his time was over. The same holds for the continuing financial crisis. In September 2008, it was presented by some as an anomaly that could be corrected through better regulations etc; now that signs of a repeated financial meltdown are gathering it is clear that we are dealing with a structural phenomenon.

We are told again and again that we are living through a debt crisis, and that we all have to share the burden and tighten our belts. All, that is, except the (very) rich. The idea of taxing them more is taboo: if we did, the argument runs, the rich would have no incentive to invest, fewer jobs would be created and we would all suffer. The only way to save ourselves from hard times is for the poor to get poorer and the rich to get richer. What should the poor do? What can they do?

Although the riots in the UK were triggered by the suspicious shooting of Mark Duggan, everyone agrees that they express a deeper unease – but of what kind? As with the car burnings in the Paris banlieues in 2005, the UK rioters had no message to deliver. (There is a clear contrast with the massive student demonstrations in November 2010, which also turned to violence. The students were making clear that they rejected the proposed reforms to higher education.) This is why it is difficult to conceive of the UK rioters in Marxist terms, as an instance of the emergence of the revolutionary subject; they fit much better the Hegelian notion of the ‘rabble’, those outside organised social space, who can express their discontent only through ‘irrational’ outbursts of destructive violence – what Hegel called ‘abstract negativity’.

There is an old story about a worker suspected of stealing: every evening, as he leaves the factory, the wheelbarrow he pushes in front of him is carefully inspected. The guards find nothing; it is always empty. Finally, the penny drops: what the worker is stealing are the wheelbarrows themselves. The guards were missing the obvious truth, just as the commentators on the riots have done. We are told that the disintegration of the Communist regimes in the early 1990s signalled the end of ideology: the time of large-scale ideological projects culminating in totalitarian catastrophe was over; we had entered a new era of rational, pragmatic politics. If the commonplace that we live in a post-ideological era is true in any sense, it can be seen in this recent outburst of violence. This was zero-degree protest, a violent action demanding nothing. In their desperate attempt to find meaning in the riots, the sociologists and editorial-writers obfuscated the enigma the riots presented.

The protesters, though underprivileged and de facto socially excluded, weren’t living on the edge of starvation. People in much worse material straits, let alone conditions of physical and ideological oppression, have been able to organise themselves into political forces with clear agendas. The fact that the rioters have no programme is therefore itself a fact to be interpreted: it tells us a great deal about our ideological-political predicament and about the kind of society we inhabit, a society which celebrates choice but in which the only available alternative to enforced democratic consensus is a blind acting out. Opposition to the system can no longer articulate itself in the form of a realistic alternative, or even as a utopian project, but can only take the shape of a meaningless outburst. What is the point of our celebrated freedom of choice when the only choice is between playing by the rules and (self-)destructive violence?

Looting with the lights on

Naomi Klein writes:

I keep hearing comparisons between the London riots and riots in other European cities – window-smashing in Athens or car bonfires in Paris. And there are parallels, to be sure: a spark set by police violence, a generation that feels forgotten.

But those events were marked by mass destruction; the looting was minor. There have, however, been other mass lootings in recent years, and perhaps we should talk about them too. There was Baghdad in the aftermath of the US invasion – a frenzy of arson and looting that emptied libraries and museums. The factories got hit too. In 2004 I visited one that used to make refrigerators. Its workers had stripped it of everything valuable, then torched it so thoroughly that the warehouse was a sculpture of buckled sheet metal.

Back then the people on cable news thought looting was highly political. They said this is what happens when a regime has no legitimacy in the eyes of the people. After watching for so long as Saddam Hussein and his sons helped themselves to whatever and whomever they wanted, many regular Iraqis felt they had earned the right to take a few things for themselves. But London isn’t Baghdad, and the British prime minister, David Cameron, is hardly Saddam, so surely there is nothing to learn there.

How about a democratic example then? Argentina, circa 2001. The economy was in freefall and thousands of people living in rough neighbourhoods (which had been thriving manufacturing zones before the neoliberal era) stormed foreign-owned superstores. They came out pushing shopping carts overflowing with the goods they could no longer afford – clothes, electronics, meat. The government called a “state of siege” to restore order; the people didn’t like that and overthrew the government.

Argentina’s mass looting was called el saqueo – the sacking. That was politically significant because it was the very same word used to describe what that country’s elites had done by selling off the country’s national assets in flagrantly corrupt privatisation deals, hiding their money offshore, then passing on the bill to the people with a brutal austerity package. Argentines understood that the saqueo of the shopping centres would not have happened without the bigger saqueo of the country, and that the real gangsters were the ones in charge. But England is not Latin America, and its riots are not political, or so we keep hearing. They are just about lawless kids taking advantage of a situation to take what isn’t theirs. And British society, Cameron tells us, abhors that kind of behaviour.

Roubini: ‘Karl Marx had it right’

Joseph Lazzaro writes:

There’s an old axiom that goes “wise is the person who appreciates candor almost as much as good news” and with that as a guide, place the forthcoming decidedly in the category of candor.

Economist Nouriel “Dr. Doom” Roubini, the New York University professor who four years ago accurately predicted the global financial crisis, said one of economist Karl Marx’s critiques of capitalism is playing itself out in the current global financial crisis.

Marx, among other theories, argued that capitalism had an internal contradiction that would cyclically lead to crises, and that, at minimum, would place pressure on the economic system.

Companies, Roubini said, are motivated to minimize costs, to save and stockpile cash, but this leads to less money in the hands of employees, which means they have less money to spend and flow back to companies.

Now, in current financial crisis, consumers, in addition to having less money to spend due to the above, are also motivated to minimize costs, to save and stockpile cash, magnifying the effect of less money flowing back to companies.

“Karl Marx had it right,” Roubini said in an interview with wsj.com. “At some point capitalism can self-destroy itself. That’s because you can not keep on shifting income from labor to capital without not having an excess capacity and a lack of aggregate demand. We thought that markets work. They are not working. What’s individually rational…is a self-destructive process.”

It’s the inequality, stupid!

Branko Milanovic writes:

As income inequality increased in the past quarter century in most parts of the world, it was strangely absent from mainstream economic discussions and publications. One would be hard-pressed, for example, to find many macroeconomic models that incorporated income or wealth inequality. Even in the run-up to and immediate aftermath of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, when income inequality returned to levels not seen since the Great Depression, it did not elicit much attention. Since then, however, the growing disparity in incomes between the rich and poor has taken a place at the top of the public agenda. From Tunisia to Egypt, from the United States to Great Britain, inequality is cited as a chief cause of revolution, economic disintegration, and unrest.

This feeling that the incomes of the rich and the poor have diverged in part reflects reality: between the 1980s and mid-2000s, income inequality rose significantly in countries as diverse as China, India, Russia, Sweden, and the United States. The Gini coefficient, a measure of economic inequality that runs from zero (everyone has the same income) to 100 (one person has the entire income of a country), has risen from around 35 to the low 40s in the United States, from 32 to 35 in India, from 30 to 37 in the United Kingdom, from less than 30 to 45 in both Russia and China, and from 22 to 29 in famously egalitarian Sweden. According to the OECD, during the same time frame, the Gini coefficient increased in 16 out of 20 rich countries. The situation was no different in the emerging market economies: in addition to in India and China, it rose in Indonesia, South Africa, and all the post-Communist countries.

For the poor, the gap has been palpable. In much of the world, the size of the economic pie has been shrinking, and the poor’s relative slice has been getting smaller. The poor’s actual income thus declined on two accounts. Despite large increase in global mean income between 1980 and 2005, excluding China, the number of people who live — or, rather, barely subsist — on an income below the absolute poverty line (1 dollar per day) remained constant, at 1.2 billion.

Record levels of unemployment for Europe’s youth

Stefan Steinberg writes:

According to the latest figures from the German Statistical Office and Eurostat, youth unemployment across Europe has increased by a staggering 25 percent in the course of the past two and a half years. The current levels of youth unemployment are the highest in Europe since the regular collection of statistics began.

In the spring of 2008, prior to the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the financial crash of that year, the official unemployment rate for youth in Europe averaged 15 percent. The latest figures from the German Statistical Office reveal that this figure has now risen to over 20 percent.

In total, 20.5 percent of young people between 15 and 24 are seeking work in the 27 states of the European Union. At the same time, these numbers conceal large differences in unemployment levels for individual European nations.

In Spain, where the social-democratc government led by Jose Luis Zapatero has introduced a series of punitive austerity programmes at the behest of the banks and the IMF, youth unemployment has doubled since 2008 and now stands at 46 percent. In second place in the European rankings is Greece, the first country to be bailed out by the European Union and to install austerity measures, with a rate of 40 percent. In third place is Italy (28 percent), followed by Portugal and Ireland (27 percent) and France (23 percent).

In Britain, where youth have taken to the streets in a wave of riots and protests in a number of the country’s main cities, unemployment hovers around 20 percent. A recent report from Britain’s Office of National Statistics reported that joblessness among people between the ages of 16 and 24 has been rising steadily, from 14.0 percent in the first quarter of 2008 to 20 percent in the first quarter of 2011—an enormous 40 percent spike in just three years.

Quantitative easing ‘is good for the rich, bad for the poor’

The Observer reports:

Quantitative easing (QE) – the Bank of England’s recession-busting policy of buying up billions of pounds of bonds – may have contributed to social unrest by exacerbating inequality, according to one City economist.

As the Bank of England considers unleashing a fresh round of QE, Dhaval Joshi, of BCA Research, argues the approach of creating electronic money pushes up share prices and profits without feeding through to wages.

“The evidence suggests that QE cash ends up overwhelmingly in profits, thereby exacerbating already extreme income inequality and the consequent social tensions that arise from it,” Joshi says in a new report.

He points out that real wages – adjusted for inflation – have fallen in both the US and UK, where QE has been a key tool for boosting growth. In Germany, meanwhile, where there has been no quantitative easing, real wages have risen.

As the Bank waded into the financial markets to spend its £200bn of newly created money, mostly on government bonds, the price of many assets, including shares and commodities such as oil, was driven up.

That helped to boost companies’ revenues, but Joshi argues that with the labour market remaining weak, employees have had little hope of bidding up their wages. “The shocking thing is, two years into an ostensible recovery, [UK] workers are actually earning less than at the depth of the recession. Real wages and salaries have fallen by £4bn. Profits are up by £11bn. The spoils of the recovery have been shared in the most unequal of ways.”

Today Maoism speaks to the world’s poor more fluently than ever

Pankaj Mishra writes:

In 2008 in Beijing I met the Chinese novelist Yu Hua shortly after he had returned from Nepal, where revolutionaries inspired by Mao Zedong had overthrown a monarchy. A young Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution, Yu Hua, like many Chinese of his generation, has extremely complicated views on Mao. Still, he was astonished, he told me, to see Nepalese Maoists singing songs from his Maoist youth – sentiments he never expected to hear again in his lifetime.

otto 20/07 Illustration by OttoIn fact, the success of Nepalese Maoists is only one sign of the “return” of Mao. In central India armed groups proudly calling themselves Maoists control a broad swath of territory, fiercely resisting the Indian government’s attempts to make the region’s resource-rich forests safe for the mining operations that, according to a recent report in Foreign Policy magazine, “major global companies like Toyota and Coca-Cola” now rely on.

And – as though not to be outdone by Mao’s foreign admirers – some Chinese have begun to carefully deploy Mao’s still deeply ambiguous memory in China. Texting Mao’s sayings to mobile phones, broadcasting “Red” songs from state-owned radio and television, and sending college students to the countryside, Bo Xilai, the ambitious communist party chief of the southwestern municipality of Chongqing, is leading an unexpected Mao revival in China.

It was the “return” of Marx, rather than of Mao, that was much heralded in academic and journalistic circles after the financial crisis of 2008. And it is true that Marxist theorists, rather than Marx himself, clearly anticipated the problems of excessive capital accumulation, and saw how eager and opportunistic investors cause wildly uneven development across regions and nations, enriching a few and impoverishing many others. But Mao’s “Sinified” and practical Marxism, which includes a blueprint for armed rebellion, appears to speak more directly to many people in poor countries.

The new geopolitics of food

Lester Brown writes:

In the United States, when world wheat prices rise by 75 percent, as they have over the last year, it means the difference between a $2 loaf of bread and a loaf costing maybe $2.10. If, however, you live in New Delhi, those skyrocketing costs really matter: A doubling in the world price of wheat actually means that the wheat you carry home from the market to hand-grind into flour for chapatis costs twice as much. And the same is true with rice. If the world price of rice doubles, so does the price of rice in your neighborhood market in Jakarta. And so does the cost of the bowl of boiled rice on an Indonesian family’s dinner table.

Welcome to the new food economics of 2011: Prices are climbing, but the impact is not at all being felt equally. For Americans, who spend less than one-tenth of their income in the supermarket, the soaring food prices we’ve seen so far this year are an annoyance, not a calamity. But for the planet’s poorest 2 billion people, who spend 50 to 70 percent of their income on food, these soaring prices may mean going from two meals a day to one. Those who are barely hanging on to the lower rungs of the global economic ladder risk losing their grip entirely. This can contribute — and it has — to revolutions and upheaval.

Already in 2011, the U.N. Food Price Index has eclipsed its previous all-time global high; as of March it had climbed for eight consecutive months. With this year’s harvest predicted to fall short, with governments in the Middle East and Africa teetering as a result of the price spikes, and with anxious markets sustaining one shock after another, food has quickly become the hidden driver of world politics. And crises like these are going to become increasingly common. The new geopolitics of food looks a whole lot more volatile — and a whole lot more contentious — than it used to. Scarcity is the new norm.

Until recently, sudden price surges just didn’t matter as much, as they were quickly followed by a return to the relatively low food prices that helped shape the political stability of the late 20th century across much of the globe. But now both the causes and consequences are ominously different.

In many ways, this is a resumption of the 2007-2008 food crisis, which subsided not because the world somehow came together to solve its grain crunch once and for all, but because the Great Recession tempered growth in demand even as favorable weather helped farmers produce the largest grain harvest on record. Historically, price spikes tended to be almost exclusively driven by unusual weather — a monsoon failure in India, a drought in the former Soviet Union, a heat wave in the U.S. Midwest. Such events were always disruptive, but thankfully infrequent. Unfortunately, today’s price hikes are driven by trends that are both elevating demand and making it more difficult to increase production: among them, a rapidly expanding population, crop-withering temperature increases, and irrigation wells running dry. Each night, there are 219,000 additional people to feed at the global dinner table.

More alarming still, the world is losing its ability to soften the effect of shortages. In response to previous price surges, the United States, the world’s largest grain producer, was effectively able to steer the world away from potential catastrophe. From the mid-20th century until 1995, the United States had either grain surpluses or idle cropland that could be planted to rescue countries in trouble. When the Indian monsoon failed in 1965, for example, President Lyndon Johnson’s administration shipped one-fifth of the U.S. wheat crop to India, successfully staving off famine. We can’t do that anymore; the safety cushion is gone.

That’s why the food crisis of 2011 is for real, and why it may bring with it yet more bread riots cum political revolutions. What if the upheavals that greeted dictators Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and Muammar al-Qaddafi in Libya (a country that imports 90 percent of its grain) are not the end of the story, but the beginning of it? Get ready, farmers and foreign ministers alike, for a new era in which world food scarcity increasingly shapes global politics.