Gary Anderson, a retired US Marine colonel, says that Julian Assange is an enemy combatant and is “as much an enemy to the United States as any Al Qaeda operative.”

Not long ago an Esquire headline writer posed the question: “Should we execute Julian Assange?” “We” being the national American vigilante?

“Lives are at risk” is one of those fire-alarm imperatives that drains blood from the brain. It sets arms and legs and vocal chords in motion, fixes the mind on red-light conclusions and turns quiet deliberation into an unaffordable luxury.

A few years ago in Reader’s Digest, Michael Crowley rang the same alarm bell when he demanded that life-threatening websites like Cryptome (a sibbling of WikiLeaks) be shutdown.

To understand what nuts and zealots can do with this sort of information [available through sites like Cryptome], recall what happened in the early 1990s when three abortion doctors were killed after pro-life extremists created “wanted” posters displaying the physicians’ names and photographs. A few years later, a website showed pictures of other abortion doctors, and listed the murdered ones with their names crossed out. Eventually the site’s Web server shut it down.

Having been an outlet for State Department and CIA propaganda in the 1940s and 50s, Reader’s Digest was already on shaky ground positioning itself as a champion of public interest, but it was the Department of Justice which revealed that on occasions Reader’s Digest itself had been a source of dangerous information.

A 1997 DoJ report on the availability of bombmaking information made it evident that the necessary know-how was not hard to come by.

Stories of crimes contained in popular literature and magazines also constitute a rich source of bombmaking information. For example, the August 1993 edition of Reader’s Digest contains an account of efforts by law enforcement officers to track down the killer of United States Court of Appeals Judge Robert S. Vance and attorney Robert Robinson. That article contained a detailed description of the explosive devices used by the bomber in committing the murders, including such information as the size of the pipe bombs, how the bombs were constructed, and what type of smokeless powder was used in their construction. According to the Arson and Explosives Division of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, in a bombing case originating in Topeka, Kansas, the devices were patterned after the bomb used to kill Judge Vance. Upon questioning, the suspect admitted to investigators that he constructed the bomb based on information contained in the Reader’s Digest article.

As Daniel Ellsberg notes, in its efforts to clamp down on embarrassing leaks, the government’s first recourse is invariably to declare that “lives are at stake”

That’s a script that they roll out — every administration rolls out — every time there’s a leak of any sort. The best justification they can find for secrecy is that lives are at stake. Actually lives are at stake as a result of silence and lies which a lot of these leaks reveal.

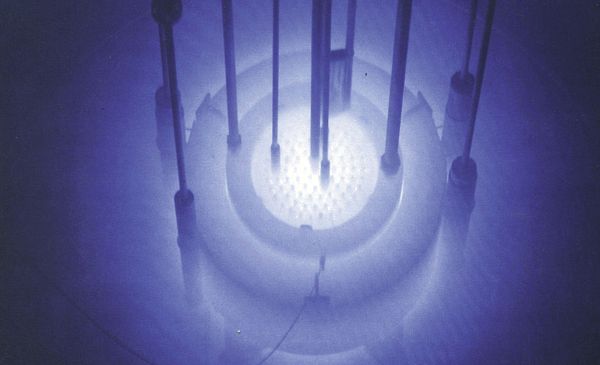

In the latest revelations from WikiLeaks, the dangers of secrecy are no more clearly evident than in what we now learn about the vulnerability of Pakistan’s nuclear stockpiles — an issue we have previously been repeatedly assured poses no immediate risk. Secretly, we now learn, America’s leading diplomats in Pakistan did not share the confidence that the administration wanted to instill among Americans whose ignorance it preferred to guard.

Less than a month after President Obama testily assured reporters in 2009 that Pakistan’s nuclear materials “will remain out of militant hands,” his ambassador here sent a secret message to Washington suggesting that she remained deeply worried.

The ambassador’s concern was a stockpile of highly enriched uranium, sitting for years near an aging research nuclear reactor in Pakistan. There was enough to build several “dirty bombs” or, in skilled hands, possibly enough for an actual nuclear bomb.

In the cable, dated May 27, 2009, the ambassador, Anne W. Patterson, reported that the Pakistani government was yet again dragging its feet on an agreement reached two years earlier to have the United States remove the material.

She wrote to senior American officials that the Pakistani government had concluded that “the ‘sensational’ international and local media coverage of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons made it impossible to proceed at this time.” A senior Pakistani official, she said, warned that if word leaked out that Americans were helping remove the fuel, the local press would certainly “portray it as the United States taking Pakistan’s nuclear weapons.”

The fuel is still there.

It may be the most unnerving evidence of the complex relationship — sometimes cooperative, often confrontational, always wary — between America and Pakistan nearly 10 years into the American-led war in Afghanistan. The cables, obtained by WikiLeaks and made available to a number of news organizations, make it clear that underneath public reassurances lie deep clashes over strategic goals on issues like Pakistan’s support for the Afghan Taliban and tolerance of Al Qaeda, and Washington’s warmer relations with India, Pakistan’s archenemy.

The issue here, however, is more complex than transparency vs secrecy. While the dangers posed by nuclear stockpiles in Pakistan — and for that matter anywhere else — should concern everyone, the overbearing relationship between the US and a client state which it has turned into a theater for remote war, has fed popular and well-founded suspicion about the intentions of the US government. Pakistanis widely believe that the United States is intent on stealing the Islamic republic’s nuclear crown jewels. Those suspicions will now be further compounded as Pakistan’s government struggles to placate competing international and domestic fears.

If transparency is the buzzword of this political moment, maybe it should be seen as a signal that a larger issue is in desperate need of remedying — an issue that WikiLeaks cannot address: that the need for transparency is symptomatic of a global deficit in trust.

We have repeatedly been given reason to expect that government leaders, corporations and other powerful institutions cannot be trusted. WikiLeaks now fuels that mistrust and those who feel threatened can either shrink behind the barricades of secrecy or acknowledge that they must address the monumental task of building confidence in the fragile idea of public service.