Yahoo News reports: The Republican Governors Association met this week in Florida to give GOP state executives a chance to rejuvenate, strategize and team-build. But during a plenary session on Wednesday, one question kept coming up: How can Republicans do a better job of talking about Occupy Wall Street?

“I’m so scared of this anti-Wall Street effort. I’m frightened to death,” said Frank Luntz, a Republican strategist and one of the nation’s foremost experts on crafting the perfect political message. “They’re having an impact on what the American people think of capitalism.”

Luntz offered tips on how Republicans could discuss the grievances of the Occupiers, and help the governors better handle all these new questions from constituents about “income inequality” and “paying your fair share.”

Yahoo News sat in on the session, and counted 10 do’s and don’ts from Luntz covering how Republicans should fight back by changing the way they discuss the movement.

1. Don’t say ‘capitalism.’

“I’m trying to get that word removed and we’re replacing it with either ‘economic freedom’ or ‘free market,’ ” Luntz said. “The public . . . still prefers capitalism to socialism, but they think capitalism is immoral. And if we’re seen as defenders of quote, Wall Street, end quote, we’ve got a problem.”

Category Archives: Occupy Movement

The real meaning of occupation

Occupy economics

Econ4 economists’ statement in support of Occupy Wall Street:

We are economists who oppose ideological cleansing in the economics profession. Equally we oppose political cleansing in the vital debate over the causes and consequences of our current economic crisis.

We support the efforts of the Occupy Wall Street movement across the country and across the globe to liberate the economy from the short-term greed of the rich and powerful one percent.

We oppose cynical and perverse attempts to misuse our police officers and public servants to expel advocates of the public good from our public spaces.

We extend our support to the vision of building an economy that works for the people, for the planet, and for the future, and we declare our solidarity with the Occupiers who are excercising our democratic right to demand economic and social justice.

(The economists who have signed this statement are listed here.)

‘We are the 99 percent’ joins the cultural and political lexicon

The New York Times reports: Most of the biggest Occupy Wall Street camps are gone. But their slogan still stands.

Whatever the long-term effects of the Occupy movement, protesters have succeeded in implanting “We are the 99 percent,” referring to the vast majority of Americans (and its implied opposite, “You are the one percent” referring to the tiny proportion of Americans with a vastly disproportionate share of wealth), into the cultural and political lexicon.

First chanted and blogged about in mid-September in New York, the slogan become a national shorthand for the income disparity. Easily grasped in its simplicity and Twitter-friendly in its brevity, the slogan has practically dared listeners to pick a side.

“We are getting nothing,” read the Tumblr blog “We Are the 99 Percent” that helped popularize the percentages, “while the other one percent is getting everything.”

Within weeks of the first encampment in Zuccotti Park in New York, politicians seized on the phrase. Democrats in Congress began to invoke the “99 percent” to press for passage of President Obama’s jobs act — but also to pursue action on mine safety, Internet access rules and voter identification laws, among others. Republicans pushed back, accusing protesters and their supporters of class warfare; Newt Gingrich this week called the “concept of the 99 and the one” both divisive and “un-American.”

Perhaps most important for the movement, there was a sevenfold increase in Google searches for the term “99 percent” between September and October and a spike in news stories about income inequality throughout the fall, heaping attention on the issues raised by activists.

“The ‘99 percent,’ and the ‘one percent,’ too, are part of our vocabulary now,” said Judith Stein, a professor of history at the City University of New York.

Soon there were income calculators (“What Percent Are You?” asked The Wall Street Journal), music playlists (an album of Woody Guthrie covers, promoted as a “soundtrack for the 99 percent”) and cheap lawn signs. And, inevitably, there were ads: a storefront near Union Square peddles “Gifts for the 99 percent.” A trailer for a Showtime television series about management consultants, “House of Lies,” describes the lead characters as “the one percent sticking it to the one percent.” A Craigslist ad for a three-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn has the come-on “Live Like the One Percent!” (in this case, in Boerum Hill).

These days, the language of the Occupy movement is being reappropriated in new ways seemingly every day. CBS ran a radio spot last that invited viewers to “occupy your couch.” On Thanksgiving, people joked online about occupying the dinner table. Now, on Facebook, holiday revelers are inviting friends to “one percent parties.”

Slogans have emerged from American protest movements, successful and otherwise, throughout history. The American Revolution furnished the world with “Give me liberty or give me death” and the still-popular “No taxation without representation.” The equal rights movement in the 1960s used the phrase “59 cents” to point out the income disparities between women and men. The civil rights movement embraced the song “We Shall Overcome” as a slogan. During the Vietnam War, protesters called on politicians to “Bring ’em Home” and “Stop the Draft.”

Occupy 2012

John Heilemann writes: In just two months of existence, OWS had scored plenty of victories: spreading from New York to more than 900 cities worldwide; introducing to the vernacular a potent catchphrase, “We are the 99 percent”; injecting into the national conversation the topic of income inequality. But OWS had also suffered setbacks. The less savory aspects of the occupations had provided the right with fuel for feral slander (Drudge: “Death, Disease Plague ‘Occupy’ Protests”) and casual caricature. Even among some protesters, there was a sense that stagnation had set in. Then came the Zuccotti clampdown—and the popular perception that it meant the end of OWS.

It’s perfectly possible that this perception will be borne out, that the raucous events of November 17 were the last gasps of a rigor-mortizing rebellion. But no one seriously involved in OWS buys a word of it. What they believe instead is that, after a brief period of retrenchment, the protests will be back even bigger and with a vengeance in the spring—when, with the unfurling of the presidential election, the whole world will be watching. Among Occupy’s organizers, there is fervid talk about occupying both the Democratic and Republican conventions. About occupying the National Mall in Washington, D.C. About, in effect, transforming 2012 into 1968 redux.

The people plotting these maneuvers are the leaders of OWS. Now, you may have heard that Occupy is a leaderless uprising. Its participants, and even the leaders themselves, are at pains to make this claim. But having spent the past month immersed in their world, I can report that a cadre of prime movers—strategists, tacticians, and logisticians; media gurus, technologists, and grand theorists—has emerged as essential to guiding OWS. For some, Occupy is an extension of years of activism; for others, their first insurrectionist rodeo. But they are now united by a single purpose: turning OWS from a brief shining moment into a bona fide movement.

That none of these people has yet become the face of OWS—its Tom Hayden or Mark Rudd, its Stokely Carmichael or H. Rap Brown—owes something to its newness. But it is also due to the way that Occupy operates. Since the sixties, starting with the backlash within the New Left against those same celebrities, the political counterculture has been ruled by loosey-goosey, bottom-up organizational precepts: horizontal and decentralized structures, an antipathy to hierarchy, a fetish for consensus. And this is true in spades of OWS. In such an environment, formal claims to leadership are invariably and forcefully rejected, leaving the processes for accomplishing anything in a state of near chaos, while at the same time opening the door to (indeed compelling) ad hoc reins-taking by those with the force of personality to gain ratification for their ideas about how to proceed. “In reality,” says Yotam Marom, one of the key OWS organizers, “movements like this are most conducive to being led by people already most conditioned to lead.”

And so in coffee shops and borrowed conference rooms around the city, far from the sound and fury in the park and on the streets, the prime movers have been doing just that—meeting, planning, talking (and talking) about the future of OWS. The debates between them have been fierce. Tensions have been laid bare, factions fomented, and ideological cleavages exposed—all of it a familiar recapitulation of the growing pains experienced by protesters of the past, from those in favor of civil rights and against the Vietnam War in the sixties to those fighting for workers’ rights in the thirties.

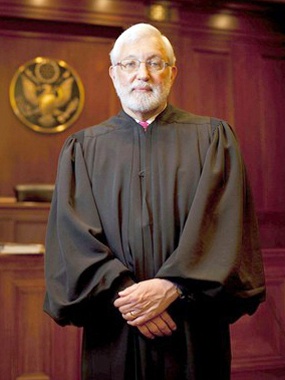

The federal judge who kicked the SEC out of bed with the banks

Matt Taibbi writes: In one of the more severe judicial ass-whippings you’ll ever see, federal Judge Jed Rakoff rejected a slap-on-the-wrist fraud settlement the SEC had cooked up for Citigroup.

I wrote about this story a few weeks back when Rakoff sent signals that he was unhappy with the SEC’s dirty deal with Citi, but yesterday he took this story several steps further.

Rakoff’s 15-page final ruling read like a political document, serving not just as a rejection of this one deal but as a broad and unequivocal indictment of the regulatory system as a whole. He particularly targeted the SEC’s longstanding practice of greenlighting relatively minor fines and financial settlements alongside de facto waivers of civil liability for the guilty – banks commit fraud and pay small fines, but in the end the SEC allows them to walk away without admitting to criminal wrongdoing.

This practice is a legal absurdity for several reasons. By accepting hundred-million-dollar fines without a full public venting of the facts, the SEC is leveling seemingly significant punishments without telling the public what the defendant is being punished for. This has essentially created a parallel or secret criminal justice system, in which both crime and punishment are adjudicated behind closed doors.

This system allows for ugly consequences in both directions. Imagine if normal criminal defendants were treated this way. Say a prosecutor and street criminal combe into a judge’s chamber and explain they’ve cooked up a deal, that the criminal doesn’t have to admit to anything or plead to any crime, but has to spend 18 months in house arrest nonetheless.

What sane judge would sign off on a deal like that without knowing exactly what the facts are? Did the criminal shoot up a nightclub and paralyze someone, or did he just sell a dimebag on the street? Is 18 months a tough sentence or a slap on the wrist? And how is it legally possible for someone to deserve an 18-month sentence without being guilty of anything?

Such deals are logical and legal absurdities, but judges have been signing off on settlements like this with Wall Street defendants for years.

Judge Rakoff blew a big hole in that practice yesterday. His ruling says secret justice is not justice, and that the government cannot hand out punishments without telling the public what the punishments are for. He wrote:

Finally, in any case like this that touches on the transparency of financial markets whose gyrations have so depressed our economy and debilitated our lives, there is an overriding public interest in knowing the truth. In much of the world, propaganda reigns, and truth is confined to secretive, fearful whispers. Even in our nation, apologists for suppressing or obscuring the truth may always be found. But the S.E.C., of all agencies, has a duty, inherent in its statutory mission, to see that the truth emerges; and if it fails to do so, this Court must not, in the name of deference or convenience, grant judicial enforcement to the agency's contrivances.

Notice the reference to how things are “in much of the world,” a subtle hint that the idea behind this ruling is to prevent a slide into third-world-style justice.

Occupy economics

Nancy Folbre writes: The Occupy Wall Street movement, displaced from some key geographic locations, now enjoys a small but significant encampment among economists.

Concerns about the impact of growing economic inequality fit neatly into a larger critique of mainstream economic theory and its deep faith in the efficiency of markets.

Many unbelievers (including me) insist that we inhabit a global capitalist system rather than an efficient market. Willingness to use the C-word (capitalism) often signals concerns about a concentration of economic power that unfairly limits individual choices, undermines political democracy, generates financial and ecological crises and limits access to alternative economic ideas.

We can’t address these concerns effectively without a wider discussion of them.

Seventy Harvard students dramatized dissatisfaction with the economics profession when they walked out of Prof. Gregory Mankiw’s introductory economics class on Nov. 2, protesting, in an open letter to their instructor, that the course “espouses a specific — and limited — view of economics that we believe perpetuates problematic and inefficient systems of economic inequality in our society today.” (Professor Mankiw, a periodic contributor to the Economic View column in the Sunday Business section of The New York Times, discussed the protest in an interview with National Public Radio.)

The event prompted online discussion of conservative bias in introductory economics textbooks, including an anti-Mankiw blog set up by Daniel MacDonald, a graduate student in my own department. Prof. John Davis of the University of Amsterdam and Marquette University posted a video arguing that economic researchers, like fish, engage in herd behavior in order to minimize individual risk.

‘It’s time to stop the bully’: Adbusters editor Kalle Lasn on Occupy Wall Street, the Israel lobby and the New York Times

Mondoweiss interviews the founder of Adbusters: When the Occupy Wall Street protests began to attract attention in the fall, everyone wanted to know where the idea to set up a permanent protest at the heart of Manhattan’s financial district came from. The answer was the mind of Kalle Lasn, the co-editor (along with Micah White) of the anti-consumerist “culture jamming” magazine Adbusters. It was Adbusters, calling for an American “Tahrir moment,” that originally put out the call to occupy Wall Street on September 17.

But not all the attention Lasn and his magazine received was positive, though. It was the New York Times coverage of Adbusters and Lasn’s role in the Occupy movement that caused him the most grief by smearing them as anti-Semitic.

“For me, the New York Times is really important right now, because it was one of the most ugly experiences of my year, where they took a couple of quick swipes at my magazine and me personally,” Lasn told Mondoweiss in a recent phone interview. “I have such huge respect for the New York Times and I subscribe to it and I’ve been reading it every morning for the last ten years of my life.”

Now, Lasn is speaking out about the New York Times‘ refusal to print his response to two articles in the newspaper that alleged Adbusters was anti-Semitic. (Read more about the controversy here, and read this New Yorker article on the origins and future of Occupy Wall Street for more about Lasn and White.)

Mondoweiss recently caught up with Lasn for an extended interview with the sixty-nine year old activist to discuss Occupy Wall Street, Palestine, the Israel lobby and more. [Continue reading…]

The New York Times also features an article on Lasn today which includes this line: “In 2004, Adbusters published an article claiming that a large percentage of neoconservatives behind American foreign policy were Jewish.” This is a classic example of the way the New York Times subtly distorts the truth.

Lasn’s article did indeed make that claim, but to call it a claim is to suspend judgement on whether it has a factual basis. It is to say that Lasn made such an assertion but the journalist reporting it was in no position to verify or refute its validity. If there was a disputable claim it was that the 50 individuals Lasn named were indeed the most influential among the neoconservative — though Lasn himself attached the caveat that “neoconservative” is for some a badge of honor while for others an unwanted label and thus identifying who is and who is not a neoconservative is not that easy. But among those 50, Lasn pointed out that half of them are Jewish.

Now if he was pointing this out because he was conducting some kind of “Jew watch”, then he could reasonably be accused of being antisemtic. But far from doing that, he was instead asserting that the centrality that many neoconservatives give to Israel’s interests is not just coincidentally related to the fact that a disproportionate number of neoconservatives are Jews. The fact that he got attacked for pointing out a fairly obvious connection, rather than indicating that he must have had an insidious motive, much more strongly indicates how easily the neoconservatives feel threatened by anyone who highlights their ties to Israel.

The origins and future of Occupy Wall Street

Mattathias Schwartz, writing for the New Yorker, traces the genesis of Occupy Wall Street, identifies a few individuals — such as Adbusters‘ Kalle Lasn and Micah M White — who certainly had a catalytic role in the movement’s formation, but finds that so far, it remains leaderless.

Those who were around at the beginning of the Occupy Wall Street movement talk about the old “vertical” left versus the new “horizontal” one. By “vertical,” they mean hierarchy and its trappings—leaders, demands, and issue-specific rallies. They mean social change as laid out by Saul Alinsky’s “Rules for Radicals” and Barack Obama’s “Dreams from My Father,” where outside organizers spur communities to action. “Horizontal” means leaderless—like the 1999 W.T.O. protests in Seattle, the Arab Spring, and even the Tea Party. Anyone can show up at a general assembly and claim a piece of the movement. This lets people feel important immediately, and gives them implicit permission to take action. It also gives a disproportionate amount of power to people like Sage [a homeless New Yorker who scornfully calls his fellow Zuccotti Park occupants, “tourists”].

One influence that is often cited by the movement is open-source software, such as Linux, an operating system that competes with Microsoft Windows and Apple’s OS but doesn’t have an owner or a chief engineer. A programmer named Linus Torvalds came up with the idea. Thousands of unpaid amateurs joined him and then eventually organized into work groups. Some coders have more influence than others, but anyone can modify the software and no one can sell it. According to Justine Tunney, who continues to help run OccupyWallSt.org, “There is leadership in the sense of deference, just as people defer to Linus Torvalds. But the moment people stop respecting Torvalds, they can fork it”—meaning copy what’s been built and use it to build something else.

In mid-October, supporters in Tokyo, Sydney, Madrid, and London held rallies; encampments sprang up in almost every major American city. Nearly all of them modelled themselves on the New York City General Assembly: with no official leaders, rotating facilitators, and no fixed set of demands. Today, endorsements of the Occupy movement can be found everywhere, from anarchist graffiti on bank walls to Al Gore’s Twitter feed. On a rain-smeared cardboard sign near the shattered window of an Oakland coffee shop that had been destroyed by a cadre of anarchists during a nighttime clash with police, someone wrote, “We’re sorry, this does not represent us.” Below that, someone else wrote, “Speak for yourself.”

At times, horizontalism can feel like utopian theatre. Its greatest invention is the “people’s mike,” which starts when someone shouts, “Mike check!” Then the crowd shouts, “Mike check!,” and then phrases (phrases!) are transmitted (are transmitted!) through mass chanting (through mass chanting!). In the same way that poker ritualizes capitalism and North Korea’s mass games ritualize totalitarianism, the people’s mike ritualizes horizontalism. The problem, though, comes when multiple people try to summon the mike simultaneously. Then it can feel a lot like anarchy.

The politics of the occupation run parallel to the mainstream left—the people’s mike was used to shout down Michele Bachmann and Governor Scott Walker, of Wisconsin, in early November. But, in the end, the point of Occupy Wall Street is not its platform so much as its form: people sit down and hash things out instead of passing their complaints on to Washington. “We are our demands,” as the slogan goes. And horizontalism seems made for this moment. It relies on people forming loose connections quickly—something that modern technology excels at.

Events in New York seemed to bear out Lasn’s hunch that the temporary eviction of the protesters from Zuccotti Park was an opportunity rather than a defeat. The organizers were quickly able to regroup and agree that they should return to the park, despite the newly enforced ban on tents. Last Thursday, the movement mounted one of its largest protests to date. Demonstrators tried to shut down the New York Stock Exchange (they failed), organized a sit-in at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge, and tussled with police in Zuccotti Park. More than two hundred people were arrested. Similar Day of Action protests temporarily blocked bridges in Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Houston, Milwaukee, Portland, and Philadelphia.

No matter what happens next, the movement’s center is likely to shift from the N.Y.C.G.A. [New York City General Assembly], just as it shifted from Adbusters, and form somewhere else, around some other circle of people, ideas, and plans. “This could be the greatest thing that I work on in my life,” Justine Tunney, of OccupyWallSt.org, said. “But the movement will have other Web sites. Over the coming weeks and months, as other occupations become more prominent, ours will slowly become irrelevant.” She sounded as though the irrelevance of her project were both inevitable and desirable. “We can’t hold on to any of that authority,” she continued. “We don’t want to.”

Van Jones and Democratic Party operatives: You do not represent the Occupy Movement

Kevin Zeese writes: The corporate media is anointing a false leader of the Occupy Movement in Van Jones of Rebuild the Dream.

The former Obama administration official, who received a golden parachute at Princeton and the Democratic think tank Center for American Progress when he left the administration, is doing what Democrats always do—see the energy of an independent movement, race to the front, then lead it down a dead end and essentially destroy it. Jones is doing the dirty work of a Democratic operative and while he and other Dem front groups pretend to support Occupiers, their real mission is to co-opt it.

Glenn Greenwald says in a recent blog, “White House-aligned groups such as the Center for American Progress have made explicity clear that they are going to try to convert OWS into a vote-producing arm for the Obama 2012 campaign.”

Before he ran to the front of the Occupy Movement, Jones’ Rebuild the Dream had been saying that its first task was to elect Democrats. Now he is claiming there will be 2000 “99% candidates” in 2012. These Democrats will be re-branded as part of the 99% movement. Democrats will now be re-labeled and marketed as part of the 99% movement. Republican operatives did the same thing to the Tea Party. Tea Party candidates, who often used to be corporate “Club for Growth” candidates, ran in the Republican Party. See, e.g. Senator Pat Toomey – before and after.

Jones is urging the Occupy Movement to “mature” and move on to an electoral phase. This would only make us a sterile part of the very problem we oppose. The electoral system is a corrupt mirage where only corporate-approved candidates are allowed to be considered seriously. At Occupy Washington, DC, we recognize that putting our time, energy and resources into elections will not produce the change we want to see. What we need to do right now is build a dynamic movement supported by independent media that stands in stark contrast to both corporate-bought-and-paid-for

parties.

The nationally coordinated crackdown on the Occupy movement

Naomi Wolf writes: US citizens of all political persuasions are still reeling from images of unparallelled police brutality in a coordinated crackdown against peaceful OWS protesters in cities across the nation this past week. An elderly woman was pepper-sprayed in the face; the scene of unresisting, supine students at UC Davis being pepper-sprayed by phalanxes of riot police went viral online; images proliferated of young women – targeted seemingly for their gender – screaming, dragged by the hair by police in riot gear; and the pictures of a young man, stunned and bleeding profusely from the head, emerged in the record of the middle-of-the-night clearing of Zuccotti Park.

But just when Americans thought we had the picture – was this crazy police and mayoral overkill, on a municipal level, in many different cities? – the picture darkened. The National Union of Journalists and the Committee to Protect Journalists issued a Freedom of Information Act request to investigate possible federal involvement with law enforcement practices that appeared to target journalists. The New York Times reported that “New York cops have arrested, punched, whacked, shoved to the ground and tossed a barrier at reporters and photographers” covering protests. Reporters were asked by NYPD to raise their hands to prove they had credentials: when many dutifully did so, they were taken, upon threat of arrest, away from the story they were covering, and penned far from the site in which the news was unfolding. Other reporters wearing press passes were arrested and roughed up by cops, after being – falsely – informed by police that “It is illegal to take pictures on the sidewalk.”

In New York, a state supreme court justice and a New York City council member were beaten up; in Berkeley, California, one of our greatest national poets, Robert Hass, was beaten with batons. The picture darkened still further when Wonkette and Washingtonsblog.com reported that the Mayor of Oakland acknowledged that the Department of Homeland Security had participated in an 18-city mayor conference call advising mayors on “how to suppress” Occupy protests.

To Europeans, the enormity of this breach may not be obvious at first. Our system of government prohibits the creation of a federalised police force, and forbids federal or militarised involvement in municipal peacekeeping.

I noticed that rightwing pundits and politicians on the TV shows on which I was appearing were all on-message against OWS. Journalist Chris Hayes reported on a leaked memo that revealed lobbyists vying for an $850,000 contract to smear Occupy. Message coordination of this kind is impossible without a full-court press at the top. This was clearly not simply a case of a freaked-out mayors’, city-by-city municipal overreaction against mess in the parks and cranky campers. As the puzzle pieces fit together, they began to show coordination against OWS at the highest national levels.

How students landed on the front lines of class war

Juan Cole writes: The deliberate pepper-spraying by campus police of nonviolent protesters at UC Davis on Friday has provoked national outrage. But the horrific incident must not cloud the real question: What led comfortable, bright, middle-class students to join the Occupy protest movement against income inequality and big-money politics in the first place?

The University of California system raised tuition by more than 9 percent this year, and the California State University system upped tuition by 12 percent. The UC system is seriously contemplating a humongous 16 percent tuition increase for fall 2012. This year, for the first time, the amount families pay in UC tuition will exceed state contributions to the university system.

University students, who face tuition hikes and state cuts to public education, find themselves victimized by the same neoliberal agenda that has created the current economic crisis, and which profoundly endangers democratic values.

The ideal that California embraced in its 1960 master plan for higher education, that it should be inexpensive and open to all Californians, is being jettisoned without much debate. The master plan exemplified the thinking on education and democracy typical of Founding Fathers such as Thomas Jefferson. In 1786, Jefferson wrote from Europe to a friend:

Preach, my dear Sir, a crusade against ignorance; establish and improve the law for educating the common people. Let our countrymen know that the people alone can protect us against these evils [of tyranny], and that the tax which will be paid for this purpose is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests and nobles who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance. …

That is, Jefferson believed that the alternative to publicly funded education was the rise of an oppressive oligarchy that would manipulate the ignorant majority.

How Occupy stopped the supercommittee

Dean Baker writes: Those who want lower deficits now also want higher unemployment. They may not know this, but that is the reality – since employers are not going to hire people because the government has cut its spending or fired government employees. The world does not work that way.

While this is the reality, the supercommittee was about turning reality on its head. Instead of the problem being a Congress that is too corrupt and/or incompetent to rein in the sort of Wall Street excesses that wrecked the economy, we were told that the problem was a Congress that could not deal with the budget deficit.

To address this invented problem, the supercommittee created an end-run around the normal congressional process. This was a long-held dream of the people financed by investment banker Peter Peterson. Their strategy was derived from the conclusion that it would not be possible to make major cuts to social security and Medicare through the normal congressional process because these programs are too popular.

Both programs enjoy enormous support across the political spectrum. Even large majorities of self-identified conservatives and Republicans are opposed to cuts in social security and Medicare. For this reason, they have wanted to set up a special process that could insulate members of Congress from political pressure. The hope was that both parties would sign on to cuts in these programs, so that voters would have nowhere to go.

However, this effort went down in flames this week. Much of the credit goes to the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement: OWS and the response it has drawn from around the country has hugely altered the political debate. It has put inequality and the incredible upward redistribution of income over the last three decades at the center of the national debate. In this context, it became impossible for Congress to back a package that had cuts to social security and Medicare at its center, while actually lowering taxes for the richest 1%, as the Republican members of the supercommittee were demanding.

Occupy Seattle protester claims police caused her miscarriage

The Guardian reports: A pregnant woman who was pepper sprayed during the Occupy Seattle protests in the US claims she had a miscarriage five days later as a result of injuries allegedly inflicted by the police.

Jennifer Fox, 19, claims that she was also struck in the stomach twice – once by a police officer’s foot and once by an officer’s bicycle – as police moved in to disperse marchers on 15 November.

A picture of Fox being carried away became one of the abiding images of the police crackdown on the Occupy Seattle protests, along with that of 84-year-old Dorli Rainey, who was pictured with pepper spray – and liquid used to treat it – dripping from her chin.

Fox told the Stranger blog: “I was standing in the middle of the crowd when the police started moving in. I was screaming, ‘I am pregnant, I am pregnant. Let me through. I am trying to get out.’ ” It was at that point, she said, that one officer lifted his foot and hit her in the stomach and another pushed his bicycle in the crowd, again hitting her in the stomach. She did not state whether she thought their actions were deliberate.

“Right before I turned, both cops lifted their pepper spray and sprayed me,” she continued. “My eyes puffed up and my eyes swelled shut.”

Video of Fox in distress at the protests was posted online on Tuesday. She can be seen telling people who have come to her assistance “I can’t see” and wailing.

#OWS: Movement surges 10% online since Zuccotti eviction

Micah Sifry writes: A week ago, early Tuesday morning November 15th, New York City police forcibly evicted the Occupy Wall Street protest encampment at Zuccotti Park. Since then, there’s been an interesting shift in how some key observers in the mainstream media talk about the movement. For example, David Carr, an influential media columnist for the New York Times, wrote yesterday as if the Occupy movement had essentially ended, with no recognition that there are still many other cities and campuses with physical occupations underway. “A tipping point is at hand,” he intoned about the movement, “now that it is not gathered around campfires.” He added, darkly, “When the spectacle disappears reporters often fold up their tents as well.”

Not to pick on Carr, whose column and work I often enjoy, but since when did reporters treat political movements like passing fads? The Times, like many other newspapers, has given plenty of coverage to the Tea Party movement–even when the available data suggested that the Tea Party had nowhere as big a following on the ground as its media presence and polling numbers suggested.

Interestingly enough, since last Tuesday’s eviction in NYC, support for the overall Occupy Wall Street movement has risen significantly online.

News organizations complain about treatment during protests

The New York Times reports: A cross-section of 13 news organizations in New York City lodged complaints on Monday about the New York Police Department’s treatment of journalists covering the Occupy Wall Street movement. Separately, 10 press clubs, unions and other groups that represent journalists called for an investigation and said they had formed a coalition to monitor police behavior going forward.

Monday’s actions were prompted by a rash of incidents on Nov. 15, when police officers impeded and even arrested reporters during and after the evictions of Occupy Wall Street protesters from Zuccotti Park, the birthplace of the two-month-old movement.

At a news conference after the park was cleared that day, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg defended the police behavior, saying that the media were kept away “to prevent a situation from getting worse and to protect members of the press.”

The news organizations said in a joint letter to the Police Department that officers had clearly violated their own procedures by threatening, arresting and injuring reporters and photographers. The letter said there were “numerous inappropriate, if not unconstitutional, actions and abuses” by the police against both “credentialed and noncredentialed journalists in the last few days.” It requested an immediate meeting with the city’s police commissioner, Raymond W. Kelly, and his chief spokesman, Paul J. Browne.

The letter was written by George Freeman, vice president and assistant general counsel for The New York Times Company, and signed by representatives for The Associated Press, The New York Post, The Daily News, Thomson Reuters, Dow Jones & Company, and three local television stations, WABC, WCBS and WNBC. It was also signed by representatives for the National Press Photographers Association, New York Press Photographers Association, Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, and the New York Press Club.

Bill McKibben, Keystone XL, and Barack Obama

Jane Mayer writes: Last spring, months before Wall Street was Occupied, civil disobedience of the kind sweeping the Arab world was hard to imagine happening here. But at Middlebury College, in Vermont, Bill McKibben, a scholar-in-residence, was leading a class discussion about Taylor Branch’s trilogy on Martin Luther King, Jr., and he began to wonder if the tactics that had won the civil-rights battle could work in this country again. McKibben, who is an author and an environmental activist (and a former New Yorker staff writer), had been alarmed by a conversation he had had about the proposed Keystone XL oil pipeline with James Hansen, the head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and one of the country’s foremost climate scientists. If the pipeline was built, it would hasten the extraction of exceptionally dirty crude oil, using huge amounts of water and heat, from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, which would then be piped across the United States, where it would be refined and burned as fuel, releasing a vast new volume of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. “What would the effect be on the climate?” McKibben asked. Hansen replied, “Essentially, it’s game over for the planet.”

It seemed a moment when, literally, a line had to be drawn in the sand. Crossing it, environmentalists believed, meant entering a more perilous phase of “extreme energy.” The tar sands’ oil deposits may be a treasure trove second in value only to Saudi Arabia’s, and the pipeline, as McKibben saw it, posed a powerful test of America’s resolve to develop cleaner sources of energy, as Barack Obama had promised to do in the 2008 campaign.

But TransCanada, the Canadian company proposing the project, was already two years into the process of applying for the necessary U.S. permit. The decision, which was expected by the end of this year, would ultimately be made by Obama, but, because the pipeline would cross an international border, the State Department had the lead role in evaluating the project, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had already indicated that she was “inclined” to approve it. Both TransCanada and the Laborers’ International Union of North America touted the construction jobs that the pipeline would create and the national-security bonus that it would confer by replacing Middle Eastern oil with Canadian.

The lineup promoting TransCanada’s interests was a textbook study in modern, bipartisan corporate influence peddling. Lobbyists ranged from the arch-conservative Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform to TransCanada’s in-house lobbyist Paul Elliott, who worked on both Hillary and Bill Clinton’s Presidential campaigns. President Clinton’s former Ambassador to Canada, Gordon Giffin, a major contributor to Hillary Clinton’s Presidential and Senate campaigns, was on TransCanada’s payroll, too. (Giffin says that he has never spoken to Secretary Clinton about the pipeline.) Most of the big oil companies also had a stake in the project. In a recent National Journal poll of “energy insiders,” opinion was virtually unanimous that the project would be approved.

Life after occupation

Arun Gupta visits Mobile, Alabama and Chicago, and asks: Can an occupation movement survive if it no longer occupies a space?

Emily Schuler, a Mobile native and college student, says the Occupy movement made her rethink her place in society, calling it “one of the best things that has ever happened to me.” Schuler says, “I love Mobile, but it’s ultra-conservative.” She explains, “I always felt like the black sheep because I sensed that the way the world was working was not good … There is a lot of pain and suffering. I think it has a lot to do with the way the system works. Because right now it’s profit over people. And it should be people over profit.”

To the world-weary in New York, a silent protest and proposition that the American system values “profit over people” may seem prosaic. And it would be prosaic were it not happening in a place like Mobile, Ala., and all over the United States. Dozens of occupiers have told us this movement is an “awakening” for them or for others.

One eye-opening aspect of our evening with Occupy Mobile was that none of these people knew each other a month before. The movement has created a new political community virtually overnight.

“We all felt alone,” Chelsy Wilson says. “Now we know that’s not the case. We’re going to try to reach out to other people who feel this wa … People say they have a new hope for Mobile. A lot of us were looking for jobs outside the city, we wanted to move away as fast as we could, and a lot of us have changed our minds. We want to stay here now.”

In smaller, conservative cities, the creation of a new community may be success enough for the movement, enabling a new network to consolidate and spread its message without a public encampment. But for larger cities that already have a strong progressive presence, the experience of Occupy Chicago is more relevant — and more sobering.

Occupy Chicago is forging ahead with maintaining a public presence despite never having established an occupation in the first place. It’s not for lack of trying. On two consecutive Saturdays in mid-October, Occupy Chicago tried to take Grant Park, known for Chicago’s head-bashing police plying their trade during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

On the day of the second action, Oct. 22, we caught up with the protest as it was marching to the horse, a statue that provided the rally cry, “Take the horse.” It was impressive compared to New York. A march some 3,000 strong, bullhorns, banners, resounding chants and marshals providing a buffer from the police. Occupy Chicago felt like any of hundreds of demonstrations I’ve been on in the last 20 years. To be fair, the energy and stakes were higher, but it seemed like protest as usual. It was far better organized than Occupy Wall Street’s chaotic peregrinations — and that was the problem.

In New York, Occupy Wall Street actions surge with electricity. No one quite seems in control because everyone is in control. Amoebic blobs of protesters break off and take the streets. Chants are thrown out, and the hive mind picks a winner. It is atavistic, often lacking signs, denied sound systems and shunning permits, but powered by hearts, lungs and passion. Exciting and unpredictable, it attracted greenhorns, drove the cops nuts, paralyzed Bloomberg for weeks and captured the world’s attention. That was why it worked and why the boot came down in the end.

In Chicago, the first time protesters tried to take the space on Oct. 15, 175 people were arrested. We were there for the second round of arrests of about 130 people. I talked to Jan Rodolfo, a 36-year-old oncology nurse and National Nurses United staff member. While preparing to be arrested along with other union members and scores of others, Rodolfo said Occupy Chicago needed “a permanent encampment because it allows the movement to grow by creating a central place for people to come. ”

Another activist said, “It would have been a big victory for the students, unions and other groups putting their efforts into the movement.”

It wouldn’t have just been a victory; it would have created a different movement. What made occupations in New York City and other cities so successful is that they brought new people into the movement in droves. Chicago has strong networks of activists, unionists and community groups, which are all involved in the Occupy movement. What they were missing was crucial: the people who were previously non-political.