Hamas and Israel: Conflicting strategies of group-based politics

By Dr. Sherifa D. Zuhur, United States Army War College, December 23, 2008

Summary

The conflict between Palestinians and Israelis has heightened since 2001, even as any perceived threat to Israel from Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, or even Syria, has declined. Israel, according to Chaim Herzog, Israel’s sixth President, had been “born in battle” and would be “obliged to live by the sword.” Yet, the Israeli government’s conquest and occupation of the West Bank and Gaza brought about a very difficult challenge, although armed resistance on a mass basis was only taken up years later in the Intifadha. Israel could not tolerate Palestinian Arabs’ resistance of their authority on the legal basis of denial of self-determination, and eventually preferred to grant some measures of self-determination while continuing to consolidate control of the Occupied Territories, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza. However, a comprehensive peace, shimmering in the distance, has eluded all, even as inter-Israeli and inter-Palestinian divisions deepened as peace danced closer before retreating.

Israel’s stance towards the democratically-elected Palestinian government headed by Hamas in 2006, and towards Palestinian national coherence–legal, territorial, political, and economic–has been a major obstacle to substantive peacemaking. The reasons for recalcitrant Israeli and Hamas stances illustrate both continuities and changes in the dynamics of conflict since the Oslo period (roughly 1994 to the al-Aqsa Intifadha of 2000). Now, more than ever, a long-term truce and negotiations are necessary. These could lead in stages to that mirage-like peace, and a new type of security regime.

The rise in popularity and strength of the Hamas (Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya, or Movement of the Islamic Resistance) Organization and its interaction with Israel is important to an understanding of Israel’s “Arab” policies and its approach to counterterrorism and counterinsurgency. The crisis brought about by the electoral success of Hamas in 2006 also challenged Western powers’ commitment to democratic change in the Middle East because Palestinians had supported the organization in the polls. Thus, the viability of a two-state solution rested on an Israeli acknowledgement of the Islamist movement, Hamas, and on Fatah’s ceding power to it.

Shifts in Israel’s stated national security objectives (and dissent over them) reveal Hamas’ placement at the nexus of Israel’s domestic, Israeli-Palestinian, and regional objectives. Israel has treated certain enemies differently than others: Iran, Hizbullah, and Islamist Palestinians (whether Hamas, supporters of Islamic Jihad, or the Islamic Movement inside Israel) all fall into a particular rubric in which Islamism–the most salient and enduring socio-religious movement in the Middle East in the wake of Arab nationalism–is identified with terrorism and insurgency rather than with group politics and identity. The antipathy to religious fervor was somewhat ironic in light of Israel’s own expanding “religious” (haredim) groups. In Israel’s earlier decades, Islamic identity politics were understood and successfully repressed, as Israelis did not want to allow any repetition of the Palestinian Mufti’s nationalism or the Qassamiyya (the armed brigades in the 1936-39 rebellion).

Yet at the same time, identity politics and religious attitudes were not eradicated, but were inside of Israel, bringing about great inequality as well as physical and psychological separation of the Jewish and non-Jewish populations. This represented efforts to control politically and physically the now 20 percent Arab minority, and dealt with the demographic threat constantly spoken of in Israel by warding off intermarriage, limiting property control and rights, and physical access. Still today, some Israeli politicians call for an exodus by Palestinian-Israelis (so-called Arab-Israelis) in some areas, who they wish would resettle in the West Bank, in the permitted areas of course.

For decades, Muslim religious properties and institutions were managed under Jewish supervision–substantial inter-Israeli conflict over that supervision notwithstanding–and this allowed for a continuing stereotype of the recalcitrant, anti-modern Muslims and Arabs who were punished for any expression of Palestinian (or Arab) nationalism by replacing them–imams or qadis, for instance–with more quiescent Israeli Muslims, and by retaining Jewish control over endowment (waqf) properties and income.

Contemporary Islamism took hold in Palestinian society, as it has throughout the Middle East and has, to a great degree, supplanted secular nationalism. This is problematic in terms of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians because the official Israeli position towards key Islamists–Iran, Hizbullah, and the Palestinian groups like Hamas, Islamic Jihad, or Hizb al-Tahrir–characterizes them as Israel-haters and terrorists. They have become the existential threat to Israel (along with Iran) since the demise of Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

Israel steadfastly rejected diplomacy and truce offers by Hamas for 8 months in 2008, despite an earlier truce that held for several years. By the spring of 2008, continued rejection of a truce was politically risky as Prime Minister Ehud Olmert teetered on the edge of indictment by his own party and finally had to announce his resignation in the summer. In fact, on his way out the door, Olmert announced a peace plan that ignores Hamas and many demands of the Palestinian Authority as a whole ever since Oslo. If the plan was merely to create a sense of Olmert’s legacy, it is not altogether clear why it offered so little compromise.

On the other hand, Israelis have for over a year been discussing the wisdom of reconquering the Gaza strip (a prospect that would aid the Fatah side of the Palestinian Authority) and also engage in “preemptive deterrence” or attacks on other states in the region. This could happen at any time if the truce between Israel and Hamas breaks down, although the risks of any of these enterprises would be high. A deal with Syria was also announced by Olmert, similarly, perhaps, to stave off his own resignation, and Syria made a counteroffer. Turkish-mediated indirect talks were to continue at the time of this writing, though they might be rescheduled. Support for an Israeli attack on Iran continues to play well in the Israeli media, despite the fact that Israelis argue fiercely about the wisdom of such a course. All of this shows flux in the region, with Israel in its customary strong, but concerned position.

Hamas emerged as the chief rival to the secularist-nationalist framework of Fatah, the dominant member of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). This occurred as Palestinians rebelled against the worsening conditions they experienced following the Oslo Peace Accords. Hamas’ political and strategic development has been both ignored and misreported in Israeli and Western sources which villainizes the group, much as the PLO was once characterized as an anti-Semitic terrorist group. Relatively few detailed treatments in English counter the media blitz that reduces Hamas to its early, now defunct, 1988 charter.

Disagreements within the Israeli military and political establishments over the national security objectives of that country reveal Hamas’ placement at the nexus of Israel’s domestic, Palestinian, and regional objectives. This process can be traced back to Ariel Sharon’s formation of the KADIMA Party and decision to withdraw unilaterally from Gaza without engaging in a peace process with Palestinians. This reflected a new understanding that Arab armies were unlikely to launch any successful attack against Israel, but Israel should focus instead on protecting its Jewish citizens via barrier methods.

This new thinking coexists alongside the long-standing policies described by Yitzhak Shamir as aggressive defense; in other words, offensives aimed at increasing Israel’s strategic depth, or attacking potential threats in neighboring countries-as in the raid on the nearly completed nuclear power facility at Osirak, Iraq, in 1981, or the mysterious Operation ORCHARD carried out on a weapons cache in Syria in September 2007, or in the invasions and ground wars (1978, 1982, 2006) in Lebanon.

Israelis considered occupied Palestinian territories valuable in land-for-peace negotiations. During the Oslo process, according to Israelis, Israel was ready to withdraw entirely to obtain peace. Actually, the value of land to trade for peace and costs of maintaining security for the settlers there, as well as containing the uprisings, were complicated equations. Palestinians and others argue that, in fact, Israel offered no more in the various proposed exchanges than the less valuable portion of the western West Bank and Gaza, and refused to deal with outstanding issues such as the fate of Palestinian refugees (4,913,993 Palestinians live outside of Israel and the occupied territories; 1,337,388 UNRWA–registered refugees–live in camps, and 3,166,781 live outside of camps), prisoners, water, and the claim of Jerusalem as a capital.

Many Arabs believe that Israel never intended the formation of a Palestinian state, and that its land-settlement policies during the Oslo period provide proof of its true intentions. Either way, the “Oslo optimism” faded away between Israelis and Palestinians with the al-Aqsa (Second) Intifadha in October 2000.

The Israeli Right, and part of its Left, claimed that the diplomatic collapse, plus Arafat’s government’s corruption, showed there was no “partner to peace.” Another segment of the Israeli Left has continued until this day to argue for land-for-peace and complete withdrawal from the territories.

According to Barry Rubin, the Israeli military felt the Palestinian threat would not increase, and that if settlers could be evacuated and a stronger line of defense erected, they might better defend their citizenry. That defense could not be achieved with suicide attacks ongoing in Israeli population centers. When earlier Israeli strategies had not achieved an end to Palestinian Islamist violence, Israelis had pushed this task onto the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Authority in the 1990s. Pointing to the failures of the Palestinian Authority, the new Israeli “securitist” (bitchonist, in Hebrew, or security-focused) strategy moved away from negotiations, and called for further separation and segregation of the Israeli population from Palestinians. Neither a full-blown physical resistance by Palestinians, including suicide attacks, or the missiles launched from Gaza could be dealt with in this manner. The first depended on granting Palestinians rights to partial self-government, and the missile attacks were negotiated in Israel’s June 2008 truce.

Israel claimed significant victories in its war against Palestinians by the use of targeted killings of leadership, boycotts, power cuts, preemptive attacks and detentions, and punishments to militant’s families, relatives, and neighborhoods etc., because its counterterrorism logic is to reduce insurgents’ organizational capability. This particular Israeli analysis rejects the idea that counterterrorist violence can spark more resistance and violence, but also admitted that Israel had not “defeated the will to resistance” [of Palestinians]. This admission suggests that the tactics employed might not be indefinitely manageable, and that Palestinians, despite every possible effort made to weaken or incriminate them, to discourage or prevent their Arab non-Palestinian supporters from defending their interests, and to buy the services of collaborators, could edge Israelis back toward comprehensive negotiations, or rise up again against them. Moshe Sharett, Israel’s second Prime Minister, once asked: “Do people consider that when military reactions outstrip in their severity the events that caused them, grave processes are set in motion which widen the gulf and thrust our neighbors into the extremist camp? How can this deterioration be halted?”

Hamas and its new wave of political thought, which had supported armed resistance along with the aim to create an Islamic society, had overtaken Fatah in popularity. Fatah, with substantial U.S. support edged closer to Israeli positions over 2006-07, promising to diminish Palestinian resistance, although President Mahmud Abbas had no means to do so, and could not even ensure Fatah’s survival in the West Bank without Hamas assent, and had been routed from Gaza.

Negotiating solely with the weaker Palestinian party–Fatah–cannot deliver the security Israel requires. This may lead Israel to reconquer the Gaza strip and continue engaging in “preemptive deterrence” or attacks on other states in the region in the longer term.

The underlying strategies of Israel and Hamas appear mutually exclusive and did not, prior to the summer of 2008, offer much hope of a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian-Arab conflict. Yet each side is still capable of revising its desired endstate and of necessary concessions to establish and preserve a long-term truce, or even a longer-term peace. [See the complete 107-page monograph [PDF]]

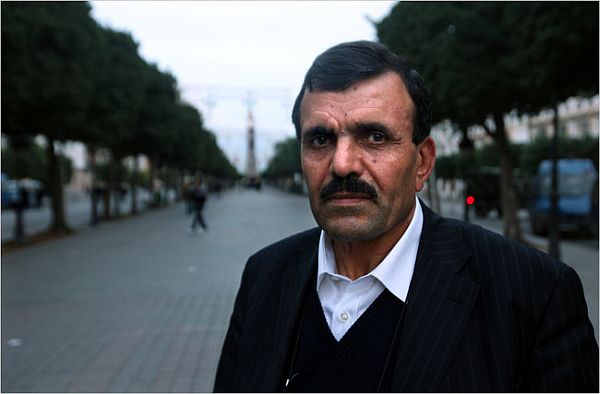

I asked [Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam chief, Maulana Fazlur] Rehman, who used to refer to the Taliban as “our boys,” if he still considered the Taliban, even those who might be firing rockets at his house, his boys. “Definitely,” he replied. “But because of America’s policies, they have gone to the extreme. I am trying to bring them back into the mainstream. We don’t disagree with the mujahedeen’s cause, but we differ over priorities. They prefer to fight, but I believe in politics.”

I asked [Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam chief, Maulana Fazlur] Rehman, who used to refer to the Taliban as “our boys,” if he still considered the Taliban, even those who might be firing rockets at his house, his boys. “Definitely,” he replied. “But because of America’s policies, they have gone to the extreme. I am trying to bring them back into the mainstream. We don’t disagree with the mujahedeen’s cause, but we differ over priorities. They prefer to fight, but I believe in politics.”