By Hannah Gurman

As the Second World War drew to a close, George Orwell looked back on the various prognoses of war and peace that had emerged in recent years:

“All political thinking for years past has been vitiated in the same way,” he observed. “People can foresee the future only when it coincides with their own wishes, and the most grossly obvious facts can be ignored when they are unwelcome.”

Over the next several years, Orwell would elaborate a dystopian vision of the emerging Cold War, a vision in which warring superpowers would use distorted and self-serving political rhetoric to battle each other and their citizens.

In recent weeks, we have reached another historic juncture. The Iraq War, or at least the American military’s role in it, is drawing to a symbolic close. To mark this moment, the U.S. Ministry of Information has put its spin machine in high gear. Orwell would have had a field day with this one. He could not have invented a more Orwellian tale than the actual story of the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq.

Here is the official version, championed in its earlier moments by Bush, Petraeus, and other congressional hawks, and now trumpeted almost as loudly by the White House and State Department: Violence is down. Iraqis are finally (it’s about time, guys) taking responsibility for their own security. The March elections were a great step forward. Iraq, we can safely say, is on the path to a brighter future.

This story marks the last chapter in the surge narrative that took root in 2006, a narrative in which General David Petraeus is credited with turning the war around. Proponents of this story know better than to declare victory, a word that has largely fallen out of the official lexicon. But the word success, which has taken its place, is everywhere. And while it doesn’t quite afford that nationalist sense of superiority to which Americans have long been accustomed, success does provide a certain contentment and satisfaction over a job well done. It allows for that perennial optimism that never quite goes out of fashion in the American way of war.

It is telling though not surprising that Obama chose a military audience to deliver his official remarks on the nominal end of America’s seven-year occupation of Iraq. Like all American, and especially all Democratic presidents, Obama rarely misses a moment to pay tribute to the troops — perhaps the only thing that no loyal American can question regardless of how unjust the wars America fights may be. “As we mark the end of America’s combat mission in Iraq,” President Obama declared, “a grateful America must pay tribute to all who served there.”

There is nothing fundamentally new in this story. It is just the latest version of a longstanding nationalist narrative in which, no matter how the story begins, the U.S. always ends up on the right side of history. For the most loyal devotees of this narrative, even Vietnam is not an exception. Were it not for that cheap congress, those pesky journalists, and those traitorous anti-war activists, they insist, we would’ve won that war too. Never mind that we had allied ourselves with a corrupt government that cared little about the people of Vietnam. Never mind that the enemy saw this as just the latest in a decades-long war against foreign occupiers. Never mind that, as Daniel Ellsberg has said, we were not just “on the wrong side” of this war. “We were the wrong side.”

As with the hawk’s version of Vietnam’s ignominious conclusion, the tale of America’s withdrawal from Iraq is characterized by contradictions, half-truths, and huge blind spots. It is a story told by officials with jobs and reputations to protect. It is a myth bought and sold by Americans who want to believe in a benevolent image of their country in the world. And most important of all, it is a fairy tale that systematically elevates the good news about Iraq and avoids any talk of the long-term devastation this war has wreaked on the people there.

In recent months, as the deadline for troop withdrawal has neared, Ambassador Christopher Hill has become a more visible prop in the administration’s official spin machine, deflecting any arrows aimed at the armor that is the official success narrative. When NPR’s Steve Inskeep asked him whether Iraq might still collapse, Hill said that he looked at the situation “in pretty optimistic terms.” That’s easy for Hill to say. He is leaving Iraq this month to become the dean of the international relations program at Denver University.

The success story is a bit harder to feed to the Iraqis who actually experience the realities on the ground in Iraq, and who, unlike Hill, will continue to face these realities on a daily basis. In an interview on Al Jazeera’s “Inside Iraq” television show in April, Jassim Al-Assawi challenged the ambassador’s rosy assessment of the March parliamentary elections, pointing out that a number of elected ex- Baathist officials had been denied seats in parliament. When questioned about the legality of this measure, as well as other serious problems of Iraqi governance, Hill tried to convince his interviewer that he was not the Iraqi government. “I’m just the US ambassador,” he said. “I’m not the prime minister” of Iraq. “I’m not a judge in Baghdad.”

Good thing. Because, according to the most recent Brookings index of Iraq, 135 of 869 judges in Iraq have been removed on charges of corruption. Overall, when it comes to corruption, Iraq ranks 176 out of 180 countries. Thus, it should come as no surprise that nine billion dollars of oil revenue intended for reconstruction has gone missing.

Of course, the state of Iraq’s political and judicial institutions has never been the strongest thread in the success narrative. The security story, on the other hand, is ostensibly on firmer ground, and has therefore figured prominently in the official version of the story. Here’s Obama on the progress of security in Iraq:

Today – even as terrorists try to derail Iraq’s progress – because of the sacrifices of our troops and their Iraqi partners, violence in Iraq continues to be near the lowest it’s been in years. And next month, we will change our military mission from combat to supporting and training Iraqi security forces. In fact, in many parts of the country, Iraqis have already taken the lead for security.

In this effort to play up the security achievements of Iraq, Obama bracketed the spikes in violence in recent months and used the word terrorist to avoid the deeper and more complex political history of both the Sadrist and Sunni insurgencies.

There is no denying that violence is down from its highest levels, and that is a good thing. But the Ministry of Information distorts all reality when it suggests that the Iraqi army and police are ready to “take the lead” in maintaining this security. As of December 2009, there were 664,000 Iraqi security forces. This reflects only the number of authorized personnel, however, and is not an indicator of operational readiness.

In September 2009, the Iraqi Army had close to 250 battalions. But only about 50 of them were deemed capable of planning, executing, and sustaining counterinsurgency operations on their own. The rest were either completely incapable or required assistance from coalition forces. This isn’t news to Iraqi military leaders. Lieutenant General Babker Zerbari, Iraq’s most senior military officer, has said that his security forces won’t be able to take the lead until 2020 and has asked the US to delay its planned withdrawal.

While the weavers of the success story have distorted the security situation in Iraq, they have hardly said a peep about the disaster that is Iraq’s infrastructure and essential services. As of February 2009, 80 percent of the population still lacked access to sanitation services, 55 percent lacked access to potable water, and 50 percent still had serious electricity shortages. As late as May 2010, Brookings estimated that 30,000-50,000 private generators were making up for shortages in the national grid.

Healthcare is also in dire straits. New studies reveal soaring cancer rates in Fallujah and other cities that were heavily targeted by U.S. forces. This news comes against the backdrop of a mass exodus of doctors from the country. Twenty thousand of Iraq’s thirty-four thousand registered physicians left Iraq after the US invasion. As of April 2009, fewer than 2,000 returned, the same as the number who were killed during the course of the war.

The shortage of doctors in Iraq is just one facet of the much bigger population displacement as a result of the war. As of January 2009, there were still 2 million Iraqi refugees living outside of the country, and as of April 2010, there were 2,764,000 internally displaced people living in Iraq.

“War against a foreign country only happens when the moneyed classes think they are going to profit from it.” –George Orwell, New Statesmen (1937)

In 2002, the State Department’s “Future of Iraq” group predicted that the toppling of the Saddam regime would usher in a period of great economic boom. That turned out not to be the case, at least not initially. Iraq’s instability kept multinational corporations out of Iraq for awhile, but in recent years, that’s been changing. In 2008 and 2009, Foreign Direct Investment went up tenfold in Iraq. Not surprisingly, officials have been framing this as great news for the country. In 2009, the website of Operation Iraqi Freedom proudly advertised that the governor of Anbar was named FDI magazine’s “Global Personality of the Year.” What the website does not advertise is that the huge oil and natural gas companies competing for Anbar’s natural resource wealth have little interest in helping the people of Anbar, but are instead focused on their bottom lines. That entails plans for using cheap foreign labor from China and other countries. It is unlikely that anything more than a small portion of their earnings will actually trickle down to ordinary Iraqis.

The oil and gas companies are not the only ones who will profit from the postwar order in Iraq. The United States military and defense industry will make out well too. Despite claims to the contrary, this is not the end of the US military presence in Iraq. In addition to the several bases that will remain active, housing the soldiers and private contractors whose titles will change to advisors, there will be an indefinite state of dependency on US-manufactured weapons and technology. Defense companies, such as ARINC will continue to make hundreds of millions providing Mi-17 helicopters and other military hardware and logistics to Iraq.

While the Ministry of Information does not advertise the reality of America’s enduring military presence in Iraq, it is quick to announce a civilian “surge” in the country. Along these lines, officials have been boasting about the massive US embassy in Baghdad. “Along with the Great Wall of China,” said Ambassador Hill, “its one of those things you can see with the naked eye from outer space. I mean it’s huge.” Indeed. At 104 acres, it is the largest U.S. embassy in the world. In addition to six apartment buildings, it has a luxury pool, as well as a water and sewage treatment plan. Stop for a second and reflect on these last two amenities. They give you some measure of what American officials really know but aren’t saying about the state of drinking water and sanitation in Iraq. The State Department has requested a mini-army to protect this Fortress America — including 24 Black Hawk helicopters and 50 bomb-resistant vehicles. Again, stop for a minute and ask yourself what this says about security in Iraq. This shadow army says a lot about what American officials really think about the state of security in Iraq.

“Who Controls the Past Controls the Future. Who Controls the Present Controls the Past” –George Orwell, 1984 (1949)

Given all the damage that remains in Iraq, it is no wonder that some Iraqis are confused and angry at the rosy pronouncements about Iraq’s path to progress. Without masking his hostility and frustration, Jassim Al-Assawi pressed ambassador Hill to explain why, despite all the problems Iraq is currently experiencing, he remains so optimistic. After waxing poetic about the heroism and drive of the Iraqi people, Hill simply insisted, “There’s no going back, only forward.”

This last statement encapsulates what is perhaps the most important function of the success narrative. All this talk about moving forward is also an insistence on not looking back, especially not to 2003. The U.S. has sought to control the past of the Iraq War by rejecting and effectively erasing it, willfully marginalizing the very act that got this whole story going in the first place. The Bush administration needed to scratch 2003 out in order to minimize its own role in the destruction of Iraq and the suffering of its people. Now, the Obama administration has picked up the eraser in order to convince everyone that this is a “responsible” withdrawal.

No matter how much the U.S government erases the past or predicts the future of Iraq, ordinary Iraqis will continue to face the more messy and complicated realities of the present. I dare Obama and everyone else in the spin machine to go to Iraq and look a child in the eyes. A child who, seven years after the US invasion, still lacks adequate housing, drinking water, sanitation, electricity, and education. Now, tell that child that the war in Iraq was a success.

Hannah Gurman is an Assistant Professor at New York University’s Gallatin School.

As an American, I look at the results of U.S. policies in the Middle East and they remind me of the T-shirt someone once gave me. It said: “Sinatra is dead. Elvis is dead. And me, I don’t feel so good.”

As an American, I look at the results of U.S. policies in the Middle East and they remind me of the T-shirt someone once gave me. It said: “Sinatra is dead. Elvis is dead. And me, I don’t feel so good.”

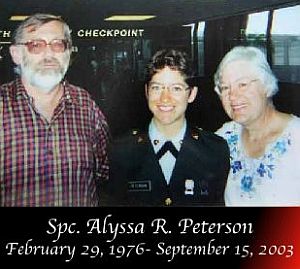

The 27-year-old’s parents didn’t even know their daughter was in Iraq until they were informed of her death. The fact that she committed suicide was concealed by the military for several more years — the most likely reason for the cover-up being that it was Peterson’s unwillingness to participate in torture that drove her to take her own life.

The 27-year-old’s parents didn’t even know their daughter was in Iraq until they were informed of her death. The fact that she committed suicide was concealed by the military for several more years — the most likely reason for the cover-up being that it was Peterson’s unwillingness to participate in torture that drove her to take her own life.