Reuters reports: The Israeli intelligence minister said on Monday that President Bashar al-Assad was ready to permit Iran to set up military bases in Syria that would pose a long-term threat to neighbouring Israel.

While formally neutral on the six-year-old Syrian civil war, Israel worries that Assad’s recent gains have given his Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah allies a foothold on its northern front.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has lobbied Russia, Assad’s most powerful backer, and the United States to curb the Iranian presence in Syria — as well as hinting that Israel could launch preemptive strikes against its arch-foe there.

In July, Moscow ratified a deal under which Damascus allowed the Russian air base in Syria’s Latakia Province to remain for almost half a century. Israeli Intelligence Minister Israel Katz said Iran could soon gain similar rights. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Lebanon

Israel’s forthcoming security dilemma

Nadav Pollak writes: In recent weeks Israel and Hizballah continued a time-honored tradition that tends to flare up in the hot months of summer: exchanging harsh words and threats regarding what each side will do to the other in the next war. These are not empty threats. Each side has the ability to inflict tremendous damage on the other. But even though both sides are ready for a war, neither Israel nor Hizballah wants one now. The main purpose of their heated rhetoric is the maintenance of deterrence and alertness. However, a recent development might raise the temperature even more.

In a speech at the Herzliya Conference on June 22, Israel’s head of military intelligence, Maj. Gen. Herzi Halevi, basically confirmed prior reports in Arab media that the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is working to establish an independent weapons industry in Lebanon focused on advanced missiles. This worrying development reportedly had become the focus of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the Israeli cabinet in recent weeks, with some wondering if there will be a point at which Israel will need to execute a preemptive strike in Lebanon that might spark a war.

In recent years Israel attacked numerous arms shipments on their way to Hizballah. These advanced arms shipments reportedly included anti-ship missiles, surface-to-air missiles, and surface-to-surface ballistic missiles. Some of these missiles are accurate and can hit strategic sites in Israel, such as military bases and important civilian infrastructure. The Israeli prime minister and minister of defense time and time again said such capabilities in the hands of Hizballah would be a red line and insisted that Israel will act to prevent the flow of advanced weapons to the militant group. According to some estimates, Israel was able to destroy 60 percent of these advanced arms shipments. This might be cause for celebration, but it seems that these airstrikes changed something in Iran’s thinking.

Israeli media reported this week that the IRGC is pushing for a Hizballah-controlled advanced weapons industrial base because this would make Israel’s interdiction operations obsolete. Tehran likely hopes that Israel will avoid attacking Hizballah in Lebanon, fearing that such a direct attack might lead to war. As such, the closer the production line is to the customer, the better.

Iran’s calculus has some merit. It appears that Israel and Hizballah have an unspoken understanding: As long as Israel does not attack Hizballah on Lebanese soil and its attacks do not result in Hizballah casualties, the organization usually chooses not to retaliate. [Continue reading…]

How the Syrian civil war has transformed Hezbollah

Jesse Rosenfeld writes: The rattle of tracer fire jolts a cellphone camera resting in the gun hole of an upper-level apartment on a shelled-out east Aleppo street. Moments after the Hezbollah fighter has fired incendiary ammunition into the neighborhood below, it’s enveloped in flames.

In another fighter’s video from the battle of Aleppo last fall, a burst of machine-gun fire erupts as Hezbollah militiamen charge forward and take up positions behind pockmarked walls. They shoot indiscriminately at an unseen enemy, which they say is the rebel force Jaysh al-Islam.

In stills taken by a Hezbollah fighter on the front lines of the Aleppo countryside just before the cease-fire was declared on December 30, fighters from Hezbollah (the Party of God) operate tanks flying the flag of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Damascus. The images provide a glimpse at how the most consequential battle of the Syrian war looked through the eyes of the conquering forces—and they indicate how crucial Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia has been in defending the Assad regime.

The destruction the Syrian government and its allies brought to east Aleppo changed the course of the nearly six-year civil war. Indeed, it could mark the beginning of the end of what started in 2011 as a popular revolution against an authoritarian regime. By laying siege to the unofficial capital of the revolution—indiscriminately bombarding it into rubble, starving and displacing its residents, and committing massacres—Assad’s counter-revolution seems to have ensured the government’s future.

Abu Hussein has been on the front lines of Assad’s strategy and features prominently in the footage and photos from Aleppo that he flips through on his phone. He is a Hezbollah commander in charge of a rapid-intervention unit of 200 fighters. They participated in the regime’s retaking of Aleppo last year as well as the ongoing fighting around Palmyra. The boisterous militant, who uses a nom de guerre because he is not authorized to speak to the media, contends that Hezbollah has been the Assad regime’s backbone, changing the course of the war on the ground. [Continue reading…]

For Syrian refugees, there is no going home

The New York Times reports: In the makeshift tent settlements that dot fields and villages in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon, Syrian refugees are digging in, pouring concrete floors, installing underground sewerage and electric wires, and starting businesses and families.

What they are not doing is packing up en masse to leave, despite exhortations from Syrian and Lebanese officials, who have declared that safety and security are on the march in neighboring Syria and that it is time for refugees to go home.

But as a new round of peace talks convened Thursday in Geneva, Syrians interviewed at a randomly selected camp in the Bekaa Valley this week offered a unanimous reality check. Their old homes are either destroyed or unsafe, they fear arrest by security forces and they know that despite recent victories by pro-government forces, the fighting and bombing are far from over. They are not going anywhere.

About 1.5 million Syrians have sought refuge in Lebanon, making up about a quarter of the population, according to officials and relief groups, and there is a widely held belief in Lebanon that refugees are a burden on the country’s economy and social structure.

Nearly six years into a war that began with a security crackdown on protests against President Bashar al-Assad, countries once eager to see him ousted are now more focused on containing the migrant crisis and defeating the Islamic State, and are willing to consider a settlement that allows Mr. Assad to remain in power.

That leaves many governments invested in vague hopes that such a settlement, however rickety or superficial, will somehow stop the metastasis of the Syrian crisis and ease fears of Islamic State terrorism — often conflated with concerns about ordinary Syrian refugees — that have fueled the rise of right-wing politicians.

And it gives many countries a strong stake in declaring Syria safe for return, even without resolving the political issues that started the conflict, including human rights abuses by the Syrian government.

Mr. Assad, Syrian officials and their allies in Lebanon are reading that mood. The Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah, has called for the return of migrants, and Lebanon’s president, Michel Aoun, has called on global powers to facilitate it.

But in a tent settlement in the village of Souairi, Syrians made clear that neither a fig-leaf deal nor an outright government victory would send many of them home.

Every family interviewed had at least one member who had disappeared after being arrested or forcibly drafted by the government. The refugees said they cared less about whether Mr. Assad stayed or went than about reforms of the security system. Without an end to torture, disappearances and arbitrary arrests, they said, they would remain wary of going back.

Virtually all said that they dreamed of going back, but that it was increasingly a dream for the next generation. [Continue reading…]

How Trump may help Hezbollah

The Times of Israel reports: Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah said he was “optimistic” now that the “fool” US President Donald Trump is in the White House, presenting what Nasrallah described as new opportunities for the Lebanon-based terror group.

Nasrallah made the comments during a televised speech broadcast on the Hezbollah terror group’s affiliate satellite channel, al-Manar.

“Neither Trump nor any other of these racists will damage the faith of children and our elders,” he said. “We are very optimistic that when a fool settles in the White House and boasts about his foolishness, this is the beginning of relief for the oppressed around the world.”

“Trump revealed the true face of the ugly, racist and unjust US administration, and we thank him for that,” Nasrallah added. [Continue reading…]

VOA reports: Hezbollah hopes that Trump is so busy pursuing his “America first” policy that he will leave a lighter U.S. footprint in the Middle East, perhaps even setting the stage for a withdrawal from the region.

“The more the U.S. policy turns toward isolationism, the more relieved the world would be from its troubles,” Nawwaf Moussawi, a member of Hezbollah in the Lebanese parliament, said last month.

Some analysts believe Hezbollah has reasons for optimism and that Trump’s possible policy in the region could, by default, strengthen the militant group.

“Trump’s reluctance toward the fight in Syria will practically provide more room for Hezbollah, a major player in Syria, to grow and flourish,” said U.K.-based Middle East scholar Scott Lucas, an editor at the EA Worldview research organization.

Others argue that Hezbollah doesn’t have the resources to create further instability in the region. [Continue reading…]

Trump’s plan for refugee zones in and around Syria will not materialize

Yezid Sayigh writes: U.S. President Donald Trump appeared to fulfill one of his many campaign promises last week. A draft of his executive order on immigration appeared on January 25 and raised the possibility of U.S. action to set up safe zones for displaced Syrians. Trump confirmed this in a television interview the same day, saying “I’ll absolutely do safe zones in Syria for the people.”

Reactions varied. Members of the Syrian opposition cautiously welcomed anything that would reduce the bloodshed in their country, while in Moscow a Kremlin spokesperson warned the proposal might “further aggravate the situation with refugees.”

The flurry of excitement was cut short, however, as the final version of the executive order published on January 27 dropped all mention of safe zones. And yet Trump returned to the theme two days later during phone calls to Saudi Arabia’s King Salman and Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Mohammad bin Zayed, in which he requested their support for safe zones in Syria (and Yemen) according to an official White House statement.

What are Trump’s real intentions? More importantly, who will police a safe zone if one is established?

The initial draft of the executive order gave some clues. Most significant was the proposal “to provide safe areas in Syria and in the surrounding region.” This suggested a rebranding exercise, in which refugee concentrations in countries such as Jordan and Lebanon or their absorption in Gulf states would be labeled “safe zones.” Expediently for Trump, this would remove the burden of financial outlay from U.S. shoulders, while precluding any need for military action to protect refugees inside Syria.

Furthermore, even if the original draft of the executive order had been preserved, it only directed the secretaries of state and defense to “produce a plan.” But contingency planning does not commit the U.S. administration to any course of action, nor does it make action probable. [Continue reading…]

Middle East Eye reports: Lebanon’s president has insisted that President Bashar al-Assad of Syria will remain in office, saying he wants Syrian refugees currently in his country to go home.

“President Assad will stay, and those who are asking for his departure are ignoring Syria,” newly elected Lebanese President Michel Aoun told French TV channel LCI on Monday.

Aoun, a former army general during the country’s civil war, was elected president in October, ending a 29-month presidential vacuum as part of a political deal that made Sunni leader Saad al-Hariri prime minister.

“We were facing the prospect of a second Libya here, but for the Assad regime that represents the only power that through its capacities restored the regime, a restoration that has united everyone and the government,” Aoun said.

Aoun is an ally of Hezbollah, Lebanon’s Iran-backed party, which is fighting in Syria on Assad’s behalf.

The Lebanese militia and political party were critical to Aoun’s ascendancy to the presidency.

“Lebanon cannot take in Syrian refugees indefinitely on its territory,” the 81-year-old said. “We hosted them for humanitarian reasons, and they must return to their country.” [Continue reading…]

Iran’s man in Beirut

Alex Rowell writes: On the morning of 13 October, 1990, the Syrian Air Force launched fighter jet strikes on the Lebanese presidential palace in Baabda, southeast of Beirut. Their target was a General Michel Aoun, an army commander appointed two years previously by an outgoing president to lead a temporary cabinet until elections could be held, who instead went rogue, moving himself into Baabda Palace and effectively declaring himself ruler of the republic — and happy to fight anyone who said otherwise.

His reign, such as it was, saw thousands killed in quixotic military campaigns against rival warlords and the Syrian army then occupying Lebanon. By October 1990, the Syrians were determined to finish him off, and the United States — of whom he had also managed to make an enemy — was willing to let them, not least as a nod of gratitude for Damascus’ assistance in the liberation of Kuwait from Saddam Hussein. “I am ready to die on the battlefield of honor rather than surrender — be sure I shall die fighting,” Aoun told a crowd of supporters on the 12th, when it was clear a final Syrian push was imminent. By noon the following day, Aoun had surrendered without firing a shot and fled to the French embassy, leaving scores of his men massacred in the ground and air onslaught, and the presidential palace in ruins. Lebanon’s fifteen-year civil war was over.

Today, the same Michel Aoun — now 81 years old — was elected to return as president to the same Baabda Palace, ending Lebanon’s thirty-month leadership vacuum after spending over a quarter of a century between exile in France and Lebanon, tirelessly plotting his eventual comeback with near-Shakespearean ambition. “I can add colours to the chameleon,” boasts the rapacious Richard III in Henry VI; “Change shapes with Proteus for advantages/ And set the murd’rous Machiavel to school.” Aoun’s long life has seen him morph from a Fort Hill-trained commander in a US-backed army (once even photographed in Israeli company) to an anti-American proxy of the Iraqi Baath regime to a Bush-supporting neoconservative fellow traveler (speaking at the Hudson Institute in favor of the Iraq War on a 2003 tour of Washington, during which he also testified to Congress in support of the Syria Accountability and Lebanese Sovereignty Restoration Act) to, most recently, a stalwart comrade of the Iranian-Syrian “Axis of Resistance.” His election today came after he and his Hezbollah ally boycotted all electoral sessions for more than two years, bluntly refusing to attend unless and until his victory was guaranteed in advance. Earlier in the month, the last of his major remaining opponents — Saad al-Hariri of the Saudi Arabia-backed Future Movement — caved in, endorsing Aoun in what he called a “sacrifice […] for the nation, the state, and stability.” [Continue reading…]

Rashida Jones: The only scary thing about Syria’s refugees is that they’re just like us

Rashida Jones writes: Immigration has become an unavoidable part of our global conversation. In part, because since 2011, the war in Syria has perpetuated a devastating refugee crisis, many fleeing the country by any means possible, putting a strain on many countries all over the world. We’ve all seen the pictures: a child trying to flee war, washing ashore in Turkey, dead. Rescued children who survived an air strike in Aleppo, covered in ash and blood. Babies rescued from the rubble. Unfortunately, as long as the war continues, heartbreaking photos of people enduring and escaping war will permeate our media.

Like a lot of us, I have been confused but concerned by the present discussion surrounding refugees. Here’s what I knew, probably similar to what you all know: we are witnessing the largest global refugee crisis in history. There is an ongoing civil war in Syria that has displaced 13.5 million people. All over the world, there is philosophical and practical conflict over borders: Do we close them, do we open them, how much, how many, etc.? And the U.S. has recently welcomed the last of its promised 10,000 Syrian refugees to our soil. Oh, yeah, and there is pretty dangerous propaganda floating around that all refugees are terrorists. Perpetuated by many unnamed international politicians, including a presidential candidate whose name rhymes with Cronald Blump.

What else did I know? I knew that the passing of the Brexit was partially inspired by the false promise of blocking entry for refugees, immigrants, and anyone who falls into the “other” category. I knew that the European countries that opened their borders have struggled with the influx of refugees. I knew that the European countries that closed their borders have struggled with bad international P.R. for being inhumane.

As a descendant of black slaves and Jewish immigrants, it’s inherently hard for me to understand why it’s acceptable for a closed-borders, anti-foreigners viewpoint to be influencing policy and popular opinion. But I try to understand. If I’m being generous, I guess I could speculate that people worldwide are scared? Scared of what they don’t know, scared of what’s next, scared of losing their comfortable lives, of having to find a way to cohabit with people whose culture, language, and religious orientation is unfamiliar. And, yes, they are irrationally scared of inviting in violent extremism. Of course we all understand the instinct to protect what is ours, but at what cost to our humanity? [Continue reading…]

In Lebanon deal, Iran wins and Saudi retreats

Reuters reports: A veteran Christian leader is set to fill Lebanon’s long-vacant presidency in a deal that underlines the ascendancy of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah movement and the diminished role of Saudi Arabia in the country.

It appears all but certain that Michel Aoun will become president next week under an unlikely proposal tabled by Sunni leader Saad al-Hariri, whose Saudi-backed coalition opposed Hezbollah for years.

Parliament will likely elect Aoun on Oct. 31. This will end one element of a paralyzing political crisis: the 29-month-long presidential vacuum. But it is also creating new tensions that may disrupt the formation of a new government expected to be led by Hariri under a deal with Aoun.

Aoun’s election will also raise questions over Western policy toward Lebanon. Lebanon’s army, guarantor of the country’s internal peace, depends on aid from the United States, which deems Hezbollah a terrorist group.

Hariri’s proposal, unthinkable a few weeks ago, appears to have been forced on him by problems at his Saudi-based construction firm, Saudi Oger, the financial backbone of his political network in Lebanon.

It marks the death throes of the Hariri-led alliance that struggled with Hezbollah for more than a decade, only to see the heavily armed Shi’ite group go from strength to strength in Lebanon and the wider region. [Continue reading…]

Amid Syrian chaos, Iran’s game plan emerges: A path to the Mediterranean

Martin Chulov reports: Not far from Mosul, a large military force is finalising plans for an advance that has been more than three decades in the making. The troops are Shia militiamen who have fought against the Islamic State, but they have not been given a direct role in the coming attack to free Iraq’s second city from its clutches.

Instead, while the Iraqi army attacks Mosul from the south, the militias will take up a blocking position to the west, stopping Isis forces from fleeing towards their last redoubt of Raqqa in Syria. Their absence is aimed at reassuring the Sunni Muslims of Mosul that the imminent recapture of the city is not a sectarian push against them. However, among Iraq’s Shia-dominated army the militia’s decision to remain aloof from the battle of Mosul is being seen as a rebuff.

Yet among the militias’ backers in Iran there is little concern. Since their inception, the Shia irregulars have made their name on the battlefields of Iraq, but they have always been central to Tehran’s ambitions elsewhere. By not helping to retake Mosul, the militias are free to drive one of its most coveted projects – securing an arc of influence across Iraq and Syria that would end at the Mediterranean Sea.

The strip of land to the west of Mosul in which the militias will operate is essential to that goal. After 12 years of conflict in Iraq and an even more savage conflict in Syria, Iran is now closer than ever to securing a land corridor that will anchor it in the region – and potentially transform the Islamic Republic’s presence on Arab lands. “They have been working extremely hard on this,” said a European official who has monitored Iran’s role in both wars for the past five years. “This is a matter of pride for them on one hand and pragmatism on the other. They will be able to move people and supplies between the Mediterranean and Tehran whenever they want, and they will do so along safe routes that are secured by their people, or their proxies.”

Interviews during the past four months with regional officials, influential Iraqis and residents of northern Syria have established that the land corridor has slowly taken shape since 2014. It is a complex route that weaves across Arab Iraq, through the Kurdish north, into Kurdish north-eastern Syria and through the battlefields north of Aleppo, where Iran and its allies are prevailing on the ground. It has been assembled under the noses of friend and foe, the latter of which has begun to sound the alarm in recent weeks. Turkey has been especially opposed, fearful of what such a development means for Iran’s relationship with the PKK (the Kurdistan Workers’ party), the restive Kurds in its midst, on whom much of the plan hinges. [Continue reading…]

Sectarian fighters mass for battle to capture east Aleppo

The Guardian reports: As the most intensive air bombardment of the war has rained down on opposition-held east Aleppo this week, an army of some 6,000 pro-government fighters has gathered on its outskirts for what they plan will be an imminent, decisive advance.

Among those poised to attack are hundreds of Syrian troops who have eyed the city from distant fixed positions since it was seized by Syrian rebels in mid-2012.

But in far greater numbers are an estimated 5,000 foreign fighters who will play a defining role in the battle – and take a lead stake in what emerges from the ruins.

The coming showdown for Aleppo is a culmination of plans made far from the warrooms of Damascus. Shia Islamic fighters have converged on the area from Iraq, Iran, Lebanon and Afghanistan to prepare for a clash that they see as a pre-ordained holy war that will determine the future of the region. [Continue reading…]

Lebanon indicts Syrian officers for twin 2013 mosque bombings

Reuters reports: Lebanon indicted two Syrian intelligence officers on Friday in connection with twin bombings at mosques in Tripoli in 2013, state media said, the deadliest attack in the city since the end of Lebanon’s civil war in 1990.

The two blasts, at the Sunni Muslim Taqwa and al-Salam mosques in the northern Lebanese city, happened within minutes of each other in August 2013 and killed more than 40 people and injured hundreds.

A Lebanese military court accused Syrian intelligence officers Muhammad Ali Ali, of the “Palestine Branch”, and Nasser Jubaan, of the “Political Security Directorate,” of planning and overseeing the attacks, Lebanon’s National News Agency said.

The court ruling announcing the indictment said investigators were still trying to uncover the names of the officials responsible for giving the two officers their orders.

According to NNA, the ruling said “the order was issued from a high-level security body within the Syrian intelligence service”. [Continue reading…]

An aristocrat’s view of Beirut

Michael Specter writes: The Sursocks are among the oldest and richest of the Christian families in Lebanon. And at the age of 94, Lady Cochrane, a Sursock by birth, may be the last great dame of the Levant. Lucid and acerbic, she seems like a cross between the Dowager Countess of Grantham and one of the less savory Mitford sisters. We had tea late one afternoon in her library, which, because it is the “coziest” place in the house, also serves as her sitting room. (This particular cozy room has 33-foot ceilings and mahogany walls and enormous 17th-century paintings. A collection of Flemish tapestries lines the entrance vestibule and dining room.)

Lady Cochrane, dressed crisply in a brown blouse, silk salmon foulard and houndstooth skirt, met me in the middle of the great hall, which features a double flight of marble stairs at its center. I asked the most obvious question first: Were you here during the civil war?

“Always,” she replied, as if my question was slightly insulting. “It’s where I live.”

Even today it is hard to walk three blocks in Beirut without seeing a building pockmarked with machine gun fire or mortar rounds, and yet the Sursock Palace was pristine. I wondered how that was possible.

“ I believe we were somehow respected,” she said matter-of-factly. “Because one day I was in the middle of the hall where you came in.” A crowd of what she referred to as “young ruffians” walked into the house. “I knew that these people would go from house to house, burgle and ruin them,” she said. (I wondered whether the words “ruffian,” and “burgle” had ever before been used to describe the vengeful packs of murderers that held sway in Beirut during the war.)

“I was alone,” she said, “and I thought, this is terrible. There must have been 50 of them. With big guns. I thought, they are just going to murder me. They saw me at a distance, and then they all went upstairs,” she said. “I tried to stay calm as best I could. After a time, they came down and I thought they must have just destroyed everything or stolen things.” She said this all with a kind of effortless serenity.

“But they did not pinch one single thing,” she continued, shaking her head in amazement 30 years later. “Except for an old poniard that had been hanging on the wall. There were two of them with exquisite Chinese handles. Very rare. They stole one and left the other where it was. I have always felt quite certain they didn’t care about the handle. Probably threw it away. They only wanted the dagger itself.”

Lady Cochrane explained that her staff had buried most of the valuables at the start of the hostilities. And there were a lot of them to bury. (“After it was over my own butler had trouble finding everything,” she said. “He hid it all so well.”)

She is horrified by the city she now inhabits. “When I was a child, Beirut was the most beautiful city. Full of gardens. Then bad government got a hold of the place. Now, after years of war and neglect it is nothing but a generalized slum.”

It was perhaps not the most nuanced analysis, but I had to ask one more question: What had happened?

“Democracy, young man,” she said. “Democracy. We never had a proper leader, and eventually the place began to fall apart.” [Continue reading…]

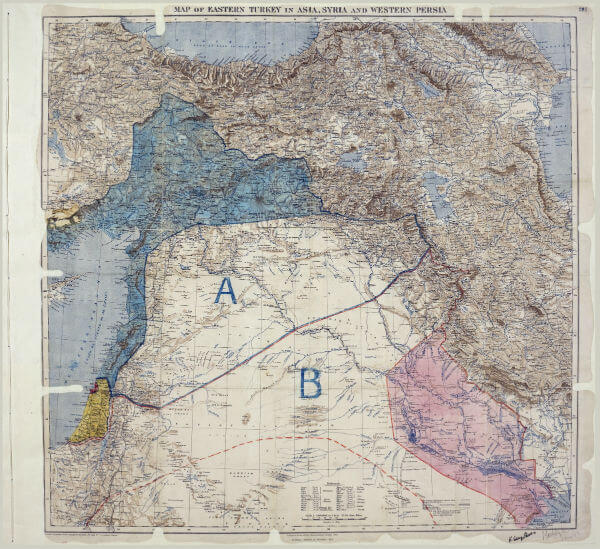

Don’t blame Sykes-Picot for the Middle East’s mess

Steven A. Cook and Amr T. Leheta write: Sometime in the 100 years since the Sykes-Picot agreement was signed, invoking its “end” became a thing among commentators, journalists, and analysts of the Middle East. Responsibility for the cliché might belong to the Independent’s Patrick Cockburn, who in June 2013 wrote an essay in the London Review of Books arguing that the agreement, which was one of the first attempts to reorder the Middle East after the Ottoman Empire’s demise, was itself in the process of dying. Since then, the meme has spread far and wide: A quick Google search reveals more than 8,600 mentions of the phrase “the end of Sykes-Picot” over the last three years.

The failure of the Sykes-Picot agreement is now part of the received wisdom about the contemporary Middle East. And it is not hard to understand why. Four states in the Middle East are failing — Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. If there is a historic shift in the region, the logic goes, then clearly the diplomatic settlements that produced the boundaries of the Levant must be crumbling. History seems to have taken its revenge on Mark Sykes and his French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, who hammered out the agreement that bears their name.

The “end of Sykes-Picot” argument is almost always followed with an exposition of the artificial nature of the countries in the region. Their borders do not make sense, according to this argument, because there are people of different religions, sects, and ethnicities within them. The current fragmentation of the Middle East is thus the result of hatreds and conflicts — struggles that “date back millennia,” as U.S. President Barack Obama said — that Sykes and Picot unwittingly released by creating these unnatural states. The answer is new borders, which will resolve all the unnecessary damage the two diplomats wrought over the previous century.

Yet this focus on Sykes-Picot is a combination of bad history and shoddy social science. And it is setting up the United States, once again, for failure in the Middle East.

For starters, it is not possible to pronounce that the maelstrom of the present Middle East killed the Sykes-Picot agreement, because the deal itself was stillborn. Sykes and Picot never negotiated state borders per se, but rather zones of influence. And while the idea of these zones lived on in the postwar agreements, the framework the two diplomats hammered out never came into existence.

Unlike the French, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s government actively began to undermine the accord as soon as Sykes signed it — in pencil. The details are complicated, but as Margaret Macmillan makes clear in her illuminating book Paris 1919, the alliance between Britain and France in the fight against the Central Powers did little to temper their colonial competition. Once the Russians dropped out of the war after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the British prime minister came to believe that the French zone that Sykes and Picot had outlined — comprising southeastern Turkey, the western part of Syria, Lebanon, and Mosul — was no longer a necessary bulwark between British positions in the region and the Russians.

Nor are the Middle East’s modern borders completely without precedent. Yes, they are the work of European diplomats and colonial officers — but these boundaries were not whimsical lines drawn on a blank map. They were based, for the most part, on pre-existing political, social, and economic realities of the region, including Ottoman administrative divisions and practices. The actual source of the boundaries of the present Middle East can be traced to the San Remo conference, which produced the Treaty of Sèvres in August 1920. Although Turkish nationalists defeated this agreement, the conference set in motion a process in which the League of Nations established British mandates over Palestine and Iraq, in 1920, and a French mandate for Syria, in 1923. The borders of the region were finalized in 1926, when the vilayet of Mosul — which Arabs and Ottomans had long associated with al-Iraq al-Arabi (Arab Iraq), made up of the provinces of Baghdad and Basra — was attached to what was then called the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq.

On a deeper level, critics of the Middle East’s present borders mistakenly assume that national borders have to be delineated naturally, along rivers and mountains, or around various identities in order to endure. It is a supposition that willfully ignores that most, if not all, of the world’s settled borders are contrived political arrangements, more often than not a result of negotiations between various powers and interests. Moreover, the populations inside these borders are not usually homogenous.

The same holds true for the Middle East, where borders were determined by balancing colonial interests against local resistance. These borders have become institutionalized in the last hundred years. In some cases — such as Egypt, Iran, or even Iraq — they have come to define lands that have long been home to largely coherent cultural identities in a way that makes sense for the modern age. Other, newer entities — Saudi Arabia and Jordan, for instance — have come into their own in the last century. While no one would have talked of a Jordanian identity centuries ago, a nation now exists, and its territorial integrity means a great deal to the Jordanian people.

The conflicts unfolding in the Middle East today, then, are not really about the legitimacy of borders or the validity of places called Syria, Iraq, or Libya. Instead, the origin of the struggles within these countries is over who has the right to rule them. The Syrian conflict, regardless of what it has evolved into today, began as an uprising by all manner of Syrians — men and women, young and old, Sunni, Shiite, Kurdish, and even Alawite — against an unfair and corrupt autocrat, just as Libyans, Egyptians, Tunisians, Yemenis, and Bahrainis did in 2010 and 2011.

The weaknesses and contradictions of authoritarian regimes are at the heart of the Middle East’s ongoing tribulations. Even the rampant ethnic and religious sectarianism is a result of this authoritarianism, which has come to define the Middle East’s state system far more than the Sykes-Picot agreement ever did. [Continue reading…]

Mustafa Badreddine, the pyromaniac playboy who led Hezbollah’s fight in Syria

Last August, Alex Rowell wrote: To close friends, he is “Dhu al-Faqar”—the name, meaning, “the cleaver of vertebrae,” of the legendary double-tipped sword given by the Prophet Muhammad to his son-in-law, Ali bin Abi Talib, the patron imam of Shia Islam. To the Kuwaiti government, who sentenced him to death in 1984 for a spate of audacious bombings on targets including the American and French embassies and the airport, he is Elias Fouad Saab. To prosecutors at the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) in The Hague, who are currently trying him in absentia on suspicion of assassinating Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri in 2005, he is Mustafa Amine Badreddine. To genteel dining companions — and multiple mistresses — entertained at his seaside home north of Beirut, he is the boat-owning, Mercedes-driving Christian jeweler, Sami Issa.

Or, rather, he was. The Frank Abagnale Jr. of jihad has found yet another preoccupation in the last few years. According to sources as discrepant as the U.S. Treasury Department and a militantly pro-Hezbollah newspaper in Beirut, the man who also goes by the name Safi Badr is currently leading the Party of God’s military intervention against the Syrian uprising, personally sitting in on meetings between President Bashar al-Assad and Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah. It’s a distinction that earned the “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” a fresh dose of American sanctions just last week. [Continue reading…]

How the curse of Sykes-Picot still haunts the Middle East

Robin Wright writes: In the Middle East, few men are pilloried these days as much as Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. Sykes, a British diplomat, travelled the same turf as T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia), served in the Boer War, inherited a baronetcy, and won a Conservative seat in Parliament. He died young, at thirty-nine, during the 1919 flu epidemic. Picot was a French lawyer and diplomat who led a long but obscure life, mainly in backwater posts, until his death, in 1950. But the two men live on in the secret agreement they were assigned to draft, during the First World War, to divide the Ottoman Empire’s vast land mass into British and French spheres of influence. The Sykes-Picot Agreement launched a nine-year process — and other deals, declarations, and treaties — that created the modern Middle East states out of the Ottoman carcass. The new borders ultimately bore little resemblance to the original Sykes-Picot map, but their map is still viewed as the root cause of much that has happened ever since.

“Hundreds of thousands have been killed because of Sykes-Picot and all the problems it created,” Nawzad Hadi Mawlood, the Governor of Iraq’s Erbil Province, told me when I saw him this spring. “It changed the course of history — and nature.”

May 16th will mark the agreement’s hundredth anniversary, amid questions over whether its borders can survive the region’s current furies. “The system in place for the past one hundred years has collapsed,” Barham Salih, a former deputy prime minister of Iraq, declared at the Sulaimani Forum, in Iraqi Kurdistan, in March. “It’s not clear what new system will take its place.”

The colonial carve-up was always vulnerable. Its map ignored local identities and political preferences. Borders were determined with a ruler — arbitrarily. At a briefing for Britain’s Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, in 1915, Sykes famously explained, “I should like to draw a line from the ‘E’ in Acre to the last ‘K’ in Kirkuk.” He slid his finger across a map, spread out on a table at No. 10 Downing Street, from what is today a city on Israel’s Mediterranean coast to the northern mountains of Iraq.

“Sykes-Picot was a mistake, for sure,” Zikri Mosa, an adviser to Kurdistan’s President Masoud Barzani, told me. “It was like a forced marriage. It was doomed from the start. It was immoral, because it decided people’s future without asking them.” [Continue reading…]

Syrian refugees in Lebanon are falling into slavery and exploitation

By Katharine Jones, Coventry University

Five years after the beginning of the Syrian conflict, Syrians now make up the largest refugee population in the world. Of the 5m women, men and children who fled Syria, more than 1m sought protection in Syria’s neighbour and former “colony”, Lebanon. But safety eludes them: hundreds of thousands of refugees who’ve fled to Lebanon now face abject poverty, living in precarious and often unsafe accommodation, and scraping by with the barest of means.

A new report from the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University, supported by the Freedom Fund, has also found that more and more refugees in Lebanon are falling prey to slavery and exploitation.

One of the biggest problems is child labour. We estimate that 60-70% of Syrian refugee children (those under 18) in Lebanon are working. Rates are even higher in the Beqaa Valley in the east of the country, where children aged as young as five pick beans, figs and potatoes. In towns and cities, Syrian children work on the streets, begging, selling flowers or tissues, shining shoes, and cleaning car windscreens. Children also work in markets, factories, auto repair shops, aluminium factories, grocery and coffee shops, in construction and running deliveries.

Syrian families in Lebanon are increasingly marrying their young teenage daughters to older Syrian men, usually aged in their twenties and thirties. While we did not find evidence of child trafficking as has been reported in the refugee camps of Jordan, girls often do not consent to these marriages, and they cannot realistically choose to leave their husbands. Once married, they very probably have no choice about whether or when to have sex, and are likely to face domestic violence.

Beyond child marriage, sexual exploitation is a growing issue for female refugees in Lebanon. Humanitarian organisations in Lebanon often talk about “survival sex” among refugee populations – for example, sex as a form of payment to people smugglers.

No way out: How Syrians are struggling to find an exit

Eleonora Vio reports: Over the last five years, close to 4.8 million Syrians have fled the conflict in their country by crossing into Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. But as the war drags on, neighbours are sealing their borders. Forced from their homes by airstrikes and fighting on multiple fronts, the vast majority of Syrian asylum seekers now have no legal escape route.

Earlier this week, EU leaders reached a hard-won deal with Turkey aimed at ending a migration crisis that has been building since last year, and that in recent weeks has seen tens of thousands of migrants and refugees stranded in Greece. But the agreement turns a blind eye to the fact that even larger numbers of asylum seekers are stranded back in Syria, unable to reach safety.

Syrians hoping to apply for asylum in Europe first have to physically get there. EU member states closed their embassies in Syria at the start of the conflict, and even embassies and consulates in neighbouring countries have been reluctant to process visa and asylum applications.

When Syria’s war erupted in March 2011, it was initially relatively easy for most refugees to leave the country. Those without the means to fly poured out in waves of tens of thousands across land borders into Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. But one by one, these exits have been restricted or closed off entirely. [Continue reading…]