Steven A. Cook and Amr T. Leheta write: Sometime in the 100 years since the Sykes-Picot agreement was signed, invoking its “end” became a thing among commentators, journalists, and analysts of the Middle East. Responsibility for the cliché might belong to the Independent’s Patrick Cockburn, who in June 2013 wrote an essay in the London Review of Books arguing that the agreement, which was one of the first attempts to reorder the Middle East after the Ottoman Empire’s demise, was itself in the process of dying. Since then, the meme has spread far and wide: A quick Google search reveals more than 8,600 mentions of the phrase “the end of Sykes-Picot” over the last three years.

The failure of the Sykes-Picot agreement is now part of the received wisdom about the contemporary Middle East. And it is not hard to understand why. Four states in the Middle East are failing — Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. If there is a historic shift in the region, the logic goes, then clearly the diplomatic settlements that produced the boundaries of the Levant must be crumbling. History seems to have taken its revenge on Mark Sykes and his French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, who hammered out the agreement that bears their name.

The “end of Sykes-Picot” argument is almost always followed with an exposition of the artificial nature of the countries in the region. Their borders do not make sense, according to this argument, because there are people of different religions, sects, and ethnicities within them. The current fragmentation of the Middle East is thus the result of hatreds and conflicts — struggles that “date back millennia,” as U.S. President Barack Obama said — that Sykes and Picot unwittingly released by creating these unnatural states. The answer is new borders, which will resolve all the unnecessary damage the two diplomats wrought over the previous century.

Yet this focus on Sykes-Picot is a combination of bad history and shoddy social science. And it is setting up the United States, once again, for failure in the Middle East.

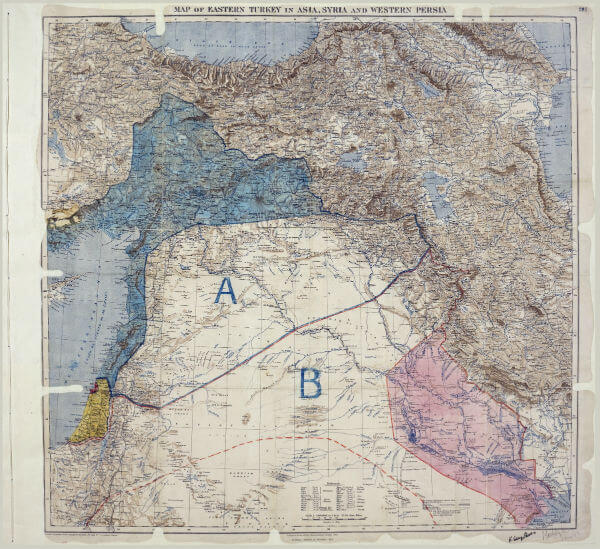

For starters, it is not possible to pronounce that the maelstrom of the present Middle East killed the Sykes-Picot agreement, because the deal itself was stillborn. Sykes and Picot never negotiated state borders per se, but rather zones of influence. And while the idea of these zones lived on in the postwar agreements, the framework the two diplomats hammered out never came into existence.

Unlike the French, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s government actively began to undermine the accord as soon as Sykes signed it — in pencil. The details are complicated, but as Margaret Macmillan makes clear in her illuminating book Paris 1919, the alliance between Britain and France in the fight against the Central Powers did little to temper their colonial competition. Once the Russians dropped out of the war after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the British prime minister came to believe that the French zone that Sykes and Picot had outlined — comprising southeastern Turkey, the western part of Syria, Lebanon, and Mosul — was no longer a necessary bulwark between British positions in the region and the Russians.

Nor are the Middle East’s modern borders completely without precedent. Yes, they are the work of European diplomats and colonial officers — but these boundaries were not whimsical lines drawn on a blank map. They were based, for the most part, on pre-existing political, social, and economic realities of the region, including Ottoman administrative divisions and practices. The actual source of the boundaries of the present Middle East can be traced to the San Remo conference, which produced the Treaty of Sèvres in August 1920. Although Turkish nationalists defeated this agreement, the conference set in motion a process in which the League of Nations established British mandates over Palestine and Iraq, in 1920, and a French mandate for Syria, in 1923. The borders of the region were finalized in 1926, when the vilayet of Mosul — which Arabs and Ottomans had long associated with al-Iraq al-Arabi (Arab Iraq), made up of the provinces of Baghdad and Basra — was attached to what was then called the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq.

On a deeper level, critics of the Middle East’s present borders mistakenly assume that national borders have to be delineated naturally, along rivers and mountains, or around various identities in order to endure. It is a supposition that willfully ignores that most, if not all, of the world’s settled borders are contrived political arrangements, more often than not a result of negotiations between various powers and interests. Moreover, the populations inside these borders are not usually homogenous.

The same holds true for the Middle East, where borders were determined by balancing colonial interests against local resistance. These borders have become institutionalized in the last hundred years. In some cases — such as Egypt, Iran, or even Iraq — they have come to define lands that have long been home to largely coherent cultural identities in a way that makes sense for the modern age. Other, newer entities — Saudi Arabia and Jordan, for instance — have come into their own in the last century. While no one would have talked of a Jordanian identity centuries ago, a nation now exists, and its territorial integrity means a great deal to the Jordanian people.

The conflicts unfolding in the Middle East today, then, are not really about the legitimacy of borders or the validity of places called Syria, Iraq, or Libya. Instead, the origin of the struggles within these countries is over who has the right to rule them. The Syrian conflict, regardless of what it has evolved into today, began as an uprising by all manner of Syrians — men and women, young and old, Sunni, Shiite, Kurdish, and even Alawite — against an unfair and corrupt autocrat, just as Libyans, Egyptians, Tunisians, Yemenis, and Bahrainis did in 2010 and 2011.

The weaknesses and contradictions of authoritarian regimes are at the heart of the Middle East’s ongoing tribulations. Even the rampant ethnic and religious sectarianism is a result of this authoritarianism, which has come to define the Middle East’s state system far more than the Sykes-Picot agreement ever did. [Continue reading…]