Richard Hamilton writes: My first job was as a lawyer. I was not a very happy or inspired lawyer. One night I was driving home listening to a radio report, and there is something very intimate about radio: a voice comes out of a machine and into the listener’s ear. With rain pounding the windscreen and only the dashboard lights and the stereo for company, I thought to myself, ‘This is what I want to do.’ So I became a radio journalist.

As broadcasters, we are told to imagine speaking to just one person. My tutor at journalism college told me that there is nothing as captivating as the human voice saying something of interest (he added that radio is better than TV because it has the best pictures). We remember where we were when we heard a particular story. Even now when I drive in my car, the memory of a scene from a radio play can be ignited by a bend in a country road or a set of traffic lights in the city.

But potent as radio seems, can a recording device ever fully replicate the experience of listening to a live storyteller? The folklorist Joseph Bruchac thinks not. ‘The presence of teller and audience, and the immediacy of the moment, are not fully captured by any form of technology,’ he wrote in a comment piece for The Guardian in 2010. ‘Unlike the insect frozen in amber, a told story is alive… The story breathes with the teller’s breath.’ And as devoted as I am to radio, my recent research into oral storytelling makes me think that Bruchac may be right. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Language/Communication

Talking to animals

As a child, I was once taken to a small sad zoo near the Yorkshire seaside town of Scarborough. There were only a handful of animals and my attention was quickly drawn by a solitary chimpanzee.

We soon sat face-to-face within arm’s reach, exchanging calls and became absorbed in what seemed like communication — even if there were no words. Before the eyes of another primate we see mirrors of inquiry. Just as much as I wanted to talk to the chimp, it seemed like he wanted to talk to me. His sorrow, like that of all captives, could not be held tight by silence.

The rest of my family eventually tired of my interest in learning how to speak chimpaneze. After all, talking to animals is something that only small children are willing to take seriously. Supposedly, it is just another childish exercise of the imagination — the kind of behavior that as we grow older we grow out of.

This notion of outgrowing a sense of kinship with other creatures implies an upward advance, yet in truth we don’t outgrow these experiences of connection, we simply move away from them. We imagine we are leaving behind something we no longer need, whereas in fact we are losing something we have forgotten how to appreciate.

Like so many other aspects of maturation, the process through which adults forget their connections to the non-human world involves a dulling of the senses. As we age, we become less alive, less attuned and less receptive to life’s boundless expressions. The insatiable curiosity we had as children, slowly withers as the mental constructs which form a known world cut away and displace our passion for exploration.

Within this known and ordered world, the idea that an adult would describe herself as an animal communicator, naturally provokes skepticism. Is this a person living in a fantasy world? Or is she engaged in a hoax, cynically exploiting the longings of others such as the desire to rediscover a lost childhood?

Whether Anna Breytenbach (who features in the video below) can see inside the minds of animals, I have no way of knowing, but that animals have minds and that they can have what we might regard as intensely human experiences — such as the feeling of loss — I have no doubt.

The cultural impact of science which is often more colored by belief than reason, suggests that whenever we reflect on the experience of animals we are perpetually at risk of falling into the trap of anthropomorphization. The greater risk, however, is that we unquestioningly accept this assumption: that even if as humans we are the culmination of an evolutionary process that goes all the way back to the formation of amino acids, at the apex of this process we somehow stand apart. We can observe the animal kingdom and yet as humans we have risen above it.

But instead, what actually sets us apart in the most significant way is not the collection of attributes that define human uniqueness, but rather it is this very idea of our separateness — the idea that we are here and nature is out there.

How computers are making people stupid

The pursuit of artificial intelligence has been driven by the assumption that if human intelligence can be replicated or advanced upon by machines then this accomplishment will in various ways serve the human good. At the same time, thanks to the technophobia promoted in some dystopian science fiction, there is a popular fear that if machines become smarter than people we will end up becoming their slaves.

It turns out that even if there are some irrational fears wrapped up in technophobia, there are good reasons to regard computing devices as a threat to human intelligence.

It’s not that we are creating machines that harbor evil designs to take over the world, but simply that each time we delegate a function of the brain to an external piece of circuitry, our mental faculties inevitably atrophy.

Use it or lose it applies just as much to the brain as it does to any other part of the body.

Carolyn Gregoire writes: Take a moment to think about the last time you memorized someone’s phone number. Was it way back when, perhaps circa 2001? And when was the last time you were at a dinner party or having a conversation with friends, when you whipped out your smartphone to Google the answer to someone’s question? Probably last week.

Technology changes the way we live our daily lives, the way we learn, and the way we use our faculties of attention — and a growing body of research has suggested that it may have profound effects on our memories (particularly the short-term, or working, memory), altering and in some cases impairing its function.

The implications of a poor working memory on our brain functioning and overall intelligence levels are difficult to over-estimate.

“The depth of our intelligence hinges on our ability to transfer information from working memory, the scratch pad of consciousness, to long-term memory, the mind’s filing system,” Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What The Internet Is Doing To Our Brains, wrote in Wired in 2010. “When facts and experiences enter our long-term memory, we are able to weave them into the complex ideas that give richness to our thought.”

While our long-term memory has a nearly unlimited capacity, the short-term memory has more limited storage, and that storage is very fragile. “A break in our attention can sweep its contents from our mind,” Carr explains.

Meanwhile, new research has found that taking photos — an increasingly ubiquitous practice in our smartphone-obsessed culture — actually hinders our ability to remember that which we’re capturing on camera.

Concerned about premature memory loss? You probably should be. Here are five things you should know about the way technology is affecting your memory.

1. Information overload makes it harder to retain information.

Even a single session of Internet usage can make it more difficult to file away information in your memory, says Erik Fransén, computer science professor at Sweden’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology. And according to Tony Schwartz, productivity expert and author of The Way We’re Working Isn’t Working, most of us aren’t able to effectively manage the overload of information we’re constantly bombarded with. [Continue reading…]

As I pointed out in a recent post, the externalization of intelligence long preceded the creation of smart phones and personal computers. Indeed, it goes all the way back to the beginning of civilization when we first learned how to transform language into a material form as the written word, thereby creating a substitute for memory.

Plato foresaw the consequences of writing.

In Phaedrus, he describes an exchange between the god Thamus, king and ruler of all Egypt, and the god Theuth, who has invented writing. Theuth, who is very proud of what he has created says: “This invention, O king, will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memories; for it is an elixir of memory and wisdom that I have discovered.” But Thamus points out that while one man has the ability to invent, the ability to judge an invention’s usefulness or harmfulness belongs to another.

If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks. What you have discovered is a recipe not for memory, but for reminder. And it is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only its semblance, for by telling them of many things without teaching them you will make them seem to know much, while for the most part they know nothing, and as men filled, not with wisdom, but with the conceit of wisdom, they will be a burden to their fellows.

Bedazzled by our ingenuity and its creations, we are fast forgetting the value of this quality that can never be implanted in a machine (or a text): wisdom.

Plato foresaw the danger of automation

Automation takes many forms and as members of a culture that reveres technology, we generally perceive automation in terms of its output: what it accomplishes, be that through manufacturing, financial transactions, flying aircraft, and so forth.

But automation doesn’t merely accomplish things for human beings; it simultaneously changes us by externalizing intelligence. The intelligence required by a person is transferred to a machine with its embedded commands, allowing the person to turn his intelligence elsewhere — or nowhere.

Automation is invariably sold on the twin claims that it offers greater efficiency, while freeing people from tedious tasks so that — at least in theory — they can give their attention to something more fulfilling.

There’s no disputing the efficiency argument — there could never have been such a thing as mass production without automation — but the promise of freedom has always been oversold. Automation has resulted in the creation of many of the most tedious, soul-destroying forms of labor in human history.

Automated systems are, however, never perfect, and when they break, they reveal the corrupting effect they have had on human intelligence — intelligence whose skilful application has atrophied through lack of use.

Nicholas Carr writes: On the evening of February 12, 2009, a Continental Connection commuter flight made its way through blustery weather between Newark, New Jersey, and Buffalo, New York. As is typical of commercial flights today, the pilots didn’t have all that much to do during the hour-long trip. The captain, Marvin Renslow, manned the controls briefly during takeoff, guiding the Bombardier Q400 turboprop into the air, then switched on the autopilot and let the software do the flying. He and his co-pilot, Rebecca Shaw, chatted — about their families, their careers, the personalities of air-traffic controllers — as the plane cruised uneventfully along its northwesterly route at 16,000 feet. The Q400 was well into its approach to the Buffalo airport, its landing gear down, its wing flaps out, when the pilot’s control yoke began to shudder noisily, a signal that the plane was losing lift and risked going into an aerodynamic stall. The autopilot disconnected, and the captain took over the controls. He reacted quickly, but he did precisely the wrong thing: he jerked back on the yoke, lifting the plane’s nose and reducing its airspeed, instead of pushing the yoke forward to gain velocity. Rather than preventing a stall, Renslow’s action caused one. The plane spun out of control, then plummeted. “We’re down,” the captain said, just before the Q400 slammed into a house in a Buffalo suburb.

The crash, which killed all 49 people on board as well as one person on the ground, should never have happened. A National Transportation Safety Board investigation concluded that the cause of the accident was pilot error. The captain’s response to the stall warning, the investigators reported, “should have been automatic, but his improper flight control inputs were inconsistent with his training” and instead revealed “startle and confusion.” An executive from the company that operated the flight, the regional carrier Colgan Air, admitted that the pilots seemed to lack “situational awareness” as the emergency unfolded.

The Buffalo crash was not an isolated incident. An eerily similar disaster, with far more casualties, occurred a few months later. On the night of May 31, an Air France Airbus A330 took off from Rio de Janeiro, bound for Paris. The jumbo jet ran into a storm over the Atlantic about three hours after takeoff. Its air-speed sensors, coated with ice, began giving faulty readings, causing the autopilot to disengage. Bewildered, the pilot flying the plane, Pierre-Cédric Bonin, yanked back on the stick. The plane rose and a stall warning sounded, but he continued to pull back heedlessly. As the plane climbed sharply, it lost velocity. The airspeed sensors began working again, providing the crew with accurate numbers. Yet Bonin continued to slow the plane. The jet stalled and began to fall. If he had simply let go of the control, the A330 would likely have righted itself. But he didn’t. The plane dropped 35,000 feet in three minutes before hitting the ocean. All 228 passengers and crew members died.

The first automatic pilot, dubbed a “metal airman” in a 1930 Popular Science article, consisted of two gyroscopes, one mounted horizontally, the other vertically, that were connected to a plane’s controls and powered by a wind-driven generator behind the propeller. The horizontal gyroscope kept the wings level, while the vertical one did the steering. Modern autopilot systems bear little resemblance to that rudimentary device. Controlled by onboard computers running immensely complex software, they gather information from electronic sensors and continuously adjust a plane’s attitude, speed, and bearings. Pilots today work inside what they call “glass cockpits.” The old analog dials and gauges are mostly gone. They’ve been replaced by banks of digital displays. Automation has become so sophisticated that on a typical passenger flight, a human pilot holds the controls for a grand total of just three minutes. What pilots spend a lot of time doing is monitoring screens and keying in data. They’ve become, it’s not much of an exaggeration to say, computer operators.

And that, many aviation and automation experts have concluded, is a problem. Overuse of automation erodes pilots’ expertise and dulls their reflexes, leading to what Jan Noyes, an ergonomics expert at Britain’s University of Bristol, terms “a de-skilling of the crew.” No one doubts that autopilot has contributed to improvements in flight safety over the years. It reduces pilot fatigue and provides advance warnings of problems, and it can keep a plane airborne should the crew become disabled. But the steady overall decline in plane crashes masks the recent arrival of “a spectacularly new type of accident,” says Raja Parasuraman, a psychology professor at George Mason University and a leading authority on automation. When an autopilot system fails, too many pilots, thrust abruptly into what has become a rare role, make mistakes. Rory Kay, a veteran United captain who has served as the top safety official of the Air Line Pilots Association, put the problem bluntly in a 2011 interview with the Associated Press: “We’re forgetting how to fly.” The Federal Aviation Administration has become so concerned that in January it issued a “safety alert” to airlines, urging them to get their pilots to do more manual flying. An overreliance on automation, the agency warned, could put planes and passengers at risk.

The experience of airlines should give us pause. It reveals that automation, for all its benefits, can take a toll on the performance and talents of those who rely on it. The implications go well beyond safety. Because automation alters how we act, how we learn, and what we know, it has an ethical dimension. The choices we make, or fail to make, about which tasks we hand off to machines shape our lives and the place we make for ourselves in the world. That has always been true, but in recent years, as the locus of labor-saving technology has shifted from machinery to software, automation has become ever more pervasive, even as its workings have become more hidden from us. Seeking convenience, speed, and efficiency, we rush to off-load work to computers without reflecting on what we might be sacrificing as a result. [Continue reading…]

Now if we think of automation as a form of forgetfulness, we will see that it extends much more deeply into civilization than just its modern manifestations through mechanization and digitization.

In the beginning was the Word and later came the Fall: the point at which language — the primary tool for shaping, expressing and sharing human intelligence — was cut adrift from the human mind and given autonomy in the form of writing.

Through the written word, thought can be immortalized and made universal. No other mechanism could have ever had such a dramatic effect on the exchange of ideas. Without writing, there would have been no such thing as humanity. But we also incurred a loss and because we have such little awareness of this loss, we might find it hard to imagine that preliterate people possessed forms of intelligence we now lack.

Plato described what writing would do — and by extension, what would happen to pilots.

In Phaedrus, he describes an exchange between the god Thamus, king and ruler of all Egypt, and the god Theuth, who has invented writing. Theuth, who is very proud of what he has created says: “This invention, O king, will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memories; for it is an elixir of memory and wisdom that I have discovered.” But Thamus points out that while one man has the ability to invent, the ability to judge an invention’s usefulness or harmfulness belongs to another.

If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks. What you have discovered is a recipe not for memory, but for reminder. And it is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only its semblance, for by telling them of many things without teaching them you will make them seem to know much, while for the most part they know nothing, and as men filled, not with wisdom, but with the conceit of wisdom, they will be a burden to their fellows.

Bedazzled by our ingenuity and its creations, we are fast forgetting the value of this quality that can never be implanted in a machine (or a text): wisdom.

Even the word itself is beginning to sound arcane — as though it should be reserved for philosophers and storytellers and is no longer something we should all strive to possess.

The inexact mirrors of the human mind

Douglas Hofstadter, author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (GEB), published in 1979, and one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence (AI), gained prominence right at a juncture when the field was abandoning its interest in human intelligence.

James Somers writes: In GEB, Hofstadter was calling for an approach to AI concerned less with solving human problems intelligently than with understanding human intelligence — at precisely the moment that such an approach, having borne so little fruit, was being abandoned. His star faded quickly. He would increasingly find himself out of a mainstream that had embraced a new imperative: to make machines perform in any way possible, with little regard for psychological plausibility.

Take Deep Blue, the IBM supercomputer that bested the chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov. Deep Blue won by brute force. For each legal move it could make at a given point in the game, it would consider its opponent’s responses, its own responses to those responses, and so on for six or more steps down the line. With a fast evaluation function, it would calculate a score for each possible position, and then make the move that led to the best score. What allowed Deep Blue to beat the world’s best humans was raw computational power. It could evaluate up to 330 million positions a second, while Kasparov could evaluate only a few dozen before having to make a decision.

Hofstadter wanted to ask: Why conquer a task if there’s no insight to be had from the victory? “Okay,” he says, “Deep Blue plays very good chess—so what? Does that tell you something about how we play chess? No. Does it tell you about how Kasparov envisions, understands a chessboard?” A brand of AI that didn’t try to answer such questions—however impressive it might have been—was, in Hofstadter’s mind, a diversion. He distanced himself from the field almost as soon as he became a part of it. “To me, as a fledgling AI person,” he says, “it was self-evident that I did not want to get involved in that trickery. It was obvious: I don’t want to be involved in passing off some fancy program’s behavior for intelligence when I know that it has nothing to do with intelligence. And I don’t know why more people aren’t that way.”

One answer is that the AI enterprise went from being worth a few million dollars in the early 1980s to billions by the end of the decade. (After Deep Blue won in 1997, the value of IBM’s stock increased by $18 billion.) The more staid an engineering discipline AI became, the more it accomplished. Today, on the strength of techniques bearing little relation to the stuff of thought, it seems to be in a kind of golden age. AI pervades heavy industry, transportation, and finance. It powers many of Google’s core functions, Netflix’s movie recommendations, Watson, Siri, autonomous drones, the self-driving car.

“The quest for ‘artificial flight’ succeeded when the Wright brothers and others stopped imitating birds and started … learning about aerodynamics,” Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig write in their leading textbook, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. AI started working when it ditched humans as a model, because it ditched them. That’s the thrust of the analogy: Airplanes don’t flap their wings; why should computers think?

It’s a compelling point. But it loses some bite when you consider what we want: a Google that knows, in the way a human would know, what you really mean when you search for something. Russell, a computer-science professor at Berkeley, said to me, “What’s the combined market cap of all of the search companies on the Web? It’s probably four hundred, five hundred billion dollars. Engines that could actually extract all that information and understand it would be worth 10 times as much.”

This, then, is the trillion-dollar question: Will the approach undergirding AI today — an approach that borrows little from the mind, that’s grounded instead in big data and big engineering — get us to where we want to go? How do you make a search engine that understands if you don’t know how you understand? Perhaps, as Russell and Norvig politely acknowledge in the last chapter of their textbook, in taking its practical turn, AI has become too much like the man who tries to get to the moon by climbing a tree: “One can report steady progress, all the way to the top of the tree.”

Consider that computers today still have trouble recognizing a handwritten A. In fact, the task is so difficult that it forms the basis for CAPTCHAs (“Completely Automated Public Turing tests to tell Computers and Humans Apart”), those widgets that require you to read distorted text and type the characters into a box before, say, letting you sign up for a Web site.

In Hofstadter’s mind, there is nothing to be surprised about. To know what all A’s have in common would be, he argued in a 1982 essay, to “understand the fluid nature of mental categories.” And that, he says, is the core of human intelligence. [Continue reading…]

Audio: Proto-Indo-European reconstructed

Here’s a story in English:

A sheep that had no wool saw horses, one of them pulling a heavy wagon, one carrying a big load, and one carrying a man quickly. The sheep said to the horses: “My heart pains me, seeing a man driving horses.” The horses said: “Listen, sheep, our hearts pain us when we see this: a man, the master, makes the wool of the sheep into a warm garment for himself. And the sheep has no wool.” Having heard this, the sheep fled into the plain.

And here is “a very educated approximation” of how that story might have sounded if spoken in Proto-Indo-European about 6,500 years ago:

(Read more at Archeology.)

The vexing question of how to sign off from an email

Ben Pobjie writes: The world of modern technology is filled with potential pitfalls to snare the unwary: how to keep sexting discreet; how to commit libel on Twitter without adverse consequence; how to stop playing the game Candy Crush.

But there are few elements of modernity as vexing as the question of how to sign off from an email. It’s an easy task if you want to look like a passive-aggressive tosser, but if you don’t, it’s one of the most fraught decisions you’ll make – and you have to make it over and over again, every day, knowing that if you slip up you might find yourself on the end of a workplace harassment complaint or scathing mockery from colleagues.

Like many people, I most often go for the safe option: the “cheers”. “Cheers, Ben” my emails tend to conclude. The trouble with “cheers” is, first of all, what does it actually mean? Am I literally cheering the person I’m writing to? Am I saying, “hooray!” at the end of my message? Or is it a toast – am I drinking to their health and electronically clinking e-glasses with them? Of course, it’s neither. “Cheers” doesn’t actually mean anything, and it’s also mind-bogglingly unoriginal: all that says to your correspondent is “I have neither the wit nor the inclination to come up with any meaningful way to end this”. [Continue reading…]

A village invents a language all its own

The New York Times reports: There are many dying languages in the world. But at least one has recently been born, created by children living in a remote village in northern Australia.

Carmel O’Shannessy, a linguist at the University of Michigan, has been studying the young people’s speech for more than a decade and has concluded that they speak neither a dialect nor the mixture of languages called a creole, but a new language with unique grammatical rules.

The language, called Warlpiri rampaku, or Light Warlpiri, is spoken only by people under 35 in Lajamanu, an isolated village of about 700 people in Australia’s Northern Territory. In all, about 350 people speak the language as their native tongue. Dr. O’Shannessy has published several studies of Light Warlpiri, the most recent in the June issue of Language.

“Many of the first speakers of this language are still alive,” said Mary Laughren, a research fellow in linguistics at the University of Queensland in Australia, who was not involved in the studies. One reason Dr. O’Shannessy’s research is so significant, she said, “is that she has been able to record and document a ‘new’ language in the very early period of its existence.” [Continue reading…]

Our conflicting interests in knowing what others think

Tim Kreider writes: Recently I received an e-mail that wasn’t meant for me, but was about me. I’d been cc’d by accident. This is one of the darker hazards of electronic communication, Reason No. 697 Why the Internet Is Bad — the dreadful consequence of hitting “reply all” instead of “reply” or “forward.” The context is that I had rented a herd of goats for reasons that aren’t relevant here and had sent out a mass e-mail with photographs of the goats attached to illustrate that a) I had goats, and b) it was good. Most of the responses I received expressed appropriate admiration and envy of my goats, but the message in question was intended not as a response to me but as an aside to some of the recipient’s co-workers, sighing over the kinds of expenditures on which I was frittering away my uncomfortable income. The word “oof” was used.

I’ve often thought that the single most devastating cyberattack a diabolical and anarchic mind could design would not be on the military or financial sector but simply to simultaneously make every e-mail and text ever sent universally public. It would be like suddenly subtracting the strong nuclear force from the universe; the fabric of society would instantly evaporate, every marriage, friendship and business partnership dissolved. Civilization, which is held together by a fragile web of tactful phrasing, polite omissions and white lies, would collapse in an apocalypse of bitter recriminations and weeping, breakups and fistfights, divorces and bankruptcies, scandals and resignations, blood feuds, litigation, wholesale slaughter in the streets and lingering ill will.

This particular e-mail was, in itself, no big deal. Tone is notoriously easy to misinterpret over e-mail, and my friend’s message could have easily been read as affectionate head shaking rather than a contemptuous eye roll. It’s frankly hard to parse the word “oof” in this context. And let’s be honest — I am terrible with money, but I’ve always liked to think of this as an endearing foible. What was surprisingly wounding wasn’t that the e-mail was insulting but simply that it was unsympathetic. Hearing other people’s uncensored opinions of you is an unpleasant reminder that you’re just another person in the world, and everyone else does not always view you in the forgiving light that you hope they do, making all allowances, always on your side. There’s something existentially alarming about finding out how little room we occupy, and how little allegiance we command, in other people’s heads. [Continue reading…]

The essayification of everything

Christy Wampole writes: Lately, you may have noticed the spate of articles and books that take interest in the essay as a flexible and very human literary form. These include “The Wayward Essay” and Phillip Lopate’s reflections on the relationship between essay and doubt, and books such as “How to Live,” Sarah Bakewell’s elegant portrait of Montaigne, the 16th-century patriarch of the genre, and an edited volume by Carl H. Klaus and Ned Stuckey-French called “Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time.”

It seems that, even in the proliferation of new forms of writing and communication before us, the essay has become a talisman of our times. What is behind our attraction to it? Is it the essay’s therapeutic properties? Because it brings miniature joys to its writer and its reader? Because it is small enough to fit in our pocket, portable like our own experiences?

I believe that the essay owes its longevity today mainly to this fact: the genre and its spirit provide an alternative to the dogmatic thinking that dominates much of social and political life in contemporary America. In fact, I would advocate a conscious and more reflective deployment of the essay’s spirit in all aspects of life as a resistance against the zealous closed-endedness of the rigid mind. I’ll call this deployment “the essayification of everything.”

What do I mean with this lofty expression?

Let’s start with form’s beginning. The word Michel de Montaigne chose to describe his prose ruminations published in 1580 was “Essais,” which, at the time, meant merely “Attempts,” as no such genre had yet been codified. This etymology is significant, as it points toward the experimental nature of essayistic writing: it involves the nuanced process of trying something out. Later on, at the end of the 16th century, Francis Bacon imported the French term into English as a title for his more boxy and solemn prose. The deal was thus sealed: essays they were and essays they would stay. There was just one problem: the discrepancy in style and substance between the texts of Michel and Francis was, like the English Channel that separated them, deep enough to drown in. I’ve always been on Team Michel, that guy who would probably show you his rash, tell you some dirty jokes, and ask you what you thought about death. I imagine, perhaps erroneously, that Team Francis tends to attract a more cocksure, buttoned-up fan base, what with all the “He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune; for they are impediments to great enterprises,” and whatnot. [Continue reading…]

Linguists identify words that have changed little in 15,000 years

You, hear me! Give this fire to that old man. Pull the black worm off the bark and give it to the mother. And no spitting in the ashes!

It’s an odd little speech but if it were spoken clearly to a band of hunter-gatherers in the Caucasus 15,000 years ago, there’s a good chance the listeners would know what you were saying. That’s because all the nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs in the four sentences are words that have descended largely unchanged from a language that died out as the glaciers were retreating at the end of the last Ice Age.

The traditional view is that words can’t survive for more than 8000 to 9000 years. Evolution, linguistic “weathering” and the adoption of replacements from other languages eventually drive ancient words to extinction, just like the dinosaurs of the Jurassic era.

But new research suggests a few words survive twice as long. Their existence suggests there was a “proto-Eurasiatic” language that was the common ancestor of about 700 languages used today – and many others that have died out over the centuries.

The descendant tongues are spoken from the Arctic to the southern tip of India. Their speakers are as apparently different as the Uighurs of western China and the Scots of the Outer Hebrides. [Continue reading…]

Evidence of universal grammar being unique to humans

Medical Xpress: How do children learn language? Many linguists believe that the stages that a child goes through when learning language mirror the stages of language development in primate evolution. In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Charles Yang of the University of Pennsylvania suggests that if this is true, then small children and non-human primates would use language the same way. He then uses statistical analysis to prove that this is not the case. The language of small children uses grammar, while language in non-human primates relies on imitation.

Yang examines two hypotheses about language development in children. One of these says that children learn how to put words together by imitating the word combinations of adults. The other states that children learn to combine words by following grammatical rules.

Linguists who support the idea that children are parroting refer to the fact that children appear to combine the same words in the same ways. For example, an English speaker can put either the determiner “a” or the determiner “the” in front of a singular noun. “A door” and “the door” are both grammatically correct, as are “a cat” and “the cat.” However, with most singular nouns, children tend to use either “a” or “the” but not both. This suggests that children are mimicking strings of words without understanding grammatical rules about how to combine the words.

Yang, however, points out that the lack of diversity in children’s word combinations could reflect the way that adults use language. Adults are more likely to use “a” with some words and “the” with others. “The bathroom” is more common than “a bathroom.” “A bath” is more common than “the bath.”

To test this conjecture, Yang analyzed language samples of young children who had just begun making two-word combinations. He calculated the number of different noun-determiner combinations someone would make if they were combining nouns and determiners independently, and found that the diversity of the children’s language matched this profile. He also found that the children’s word combinations were much more diverse than they would be if they were simply imitating word strings.

Yang also studied language diversity in Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who knows American Sign Language. Nim’s word combinations are much less diverse than would be expected if he were combining words independently. This indicates that he is probably mimicking, rather than using grammar.

This difference in language use indicates that human children do not acquire language in the same way that non-human primates do. Young children learn rules of grammar very quickly, while a chimpanzee who has spent many years learning language continues to imitate rather than combine words based on grammatical rules.

How can we stlil raed words wehn teh lettres are jmbuled up?

The Economic and Social Research Council: Researchers in the UK have taken an important step towards understanding how the human brain ‘decodes’ letters on a page to read a word. The work, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), will help psychologists unravel the subtle thinking mechanisms involved in reading, and could provide solutions for helping people who find it difficult to read, for example in conditions such as dyslexia.

In order to read successfully, readers need not only to identify the letters in words, but also to accurately code the positions of those letters, so that they can distinguish words like CAT and ACT. At the same time, however, it’s clear that raeders can dael wtih wodrs in wihch not all teh leettrs aer in thier corerct psotiions.

“How the brain can make sense of some jumbled sequences of letters but not others is a key question that psychologists need to answer to understand the code that the brain uses when reading,” says Professor Colin Davis of Royal Holloway, University of London, who led the research.

For many years researchers have used a standard psychological test to try to work out which sequences of letters in a word are important cues that the brain uses, where jumbled words are flashed momentarily on a screen to see if they help the brain to recognise the properly spelt word.

But, this technique had limitations that made it impossible to probe more extreme rearrangements of sequences of letters. Professor Davis’s team used computer simulations to work out that a simple modification to the test would allow it to question these more complex changes to words. This increases the test’s sensitivity significantly and makes it far more valuable for comparing different coding theories.

“For example, if we take the word VACATION and change it to AVACITNO, previously the test would not tell us if the brain recognises it as VACATION because other words such as AVOCADO or AVIATION might start popping into the person’s head,” says Professor Davis. “With our modification we can show that indeed the brain does relate AVACITNO to VACATION, and this starts to give us much more of an insight into the nature of the code that the brain is using – something that was not possible with the existing test.”

The modified test should allow researchers not only to crack the code that the brain uses to make sense of strings of letters, but also to examine differences between individuals – how a ‘good’ reader decodes letter sequences compared with someone who finds reading difficult.

“These kinds of methods can be very sensitive to individual differences in reading ability and we are starting to get a better idea of some of the issues that underpin people’s difficulty in reading,” says Professor Davis. Ultimately, this could lead to new approaches to helping people to overcome reading problems.

We are what we quote

Speech is quotation. That is unless someone chooses to construct a language of their own and is content to be understood by no one else.

There is in practice only so far we can go in making words our own, since a word’s ability to possess meaning depends on it being shared. And virtually all of these meanings come used — rare is the word and meaning freshly minted. And yet from this supply of endlessly re-used terms, we can construct a limitless number of novel pieces of language. Duplication and uniqueness get wrapped together.

Out of this endless supply of new sentences however, some turn out so well-formed they demand repetition.

Geoffrey O’Brien asks: What is the use of quotations? They have of, course, their practical applications for after-dinner speakers or for editorialists looking to buttress their arguments. They also make marvelous filler for otherwise uninspired conversations. But the gathering of such fragments responds to a much deeper compulsion. It resonates with the timeless desire to seize on the minimal remnant — the tiniest identifiable gesture — out of which the world could, in a pinch, be reconstructed. Libraries may go under, cultures may go under, but single memorizable bits of rhyme and discourse persist over centuries. Shattered wholes reach us in small disconnected pieces, like the lines of the poet Sappho preserved in ancient treatises. To collect those pieces, to extrapolate lost worlds from them, to create a larger map of the human universe by laying many such pieces side by side: this can become a fever, and one that has afflicted writers of all eras.

Anyone, of course, might develop a passion for quotes, but for a writer it’s a particularly intimate connection. A good quotation can serve as a model for one’s own work, a perpetual challenge with the neatness and self-sufficiency of its structure laid bare in the mind. How does it work? How might a quotation be done differently, with the materials and urgencies of a different moment? Perhaps writers should begin, in fact, by inwardly uttering again what has already been uttered, to get the feel of it and to savor its full power.

Quotes are the actual fabric with which the mind weaves: internalizing them, but also turning them inside out, quarreling with them, adding to them, wandering through their architecture as if a single sentence were an expansible labyrinthine space.

Evidence of innate language capabilities: discrimination of syllables three months prior to birth

Medical Xpress: A team of French researchers has discovered that the human brain is capable of distinguishing between different types of syllables as early as three months prior to full term birth. As they describe in their paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team found via brain scans that babies born up to three months premature are capable of some language processing. Many studies have been conducted on full term babies to try to understand the degree of mental capabilities at birth. Results from such studies have shown that babies are able to distinguish their mother’s voice from others, for example, and can even recognize the elements of short stories. Still puzzling however, is whether some of what newborns are able to demonstrate is innate, or learned immediately after birth. To learn more, the researchers enlisted the assistance of several parents of premature babies and their offspring. Babies born as early as 28 weeks (full term is 37 weeks) had their brains scanned using bedside functional optical imaging, while sounds (soft voices) were played for them. Three months prior to full term, the team notes, neurons in the brain are still migrating to what will be their final destination locations and initial connections between the upper brain regions are still forming—also neural linkages between the ears and brain are still being created. All of this indicates a brain that is still very much in flux and in the process of becoming the phenomenally complicated mass that humans are known for, which would seem to suggest that very limited if any communication skills would have developed.

The researchers found, however, that even at a time when the brain hasn’t fully developed, the premature infants were able to tell the difference between female versus male voices, and to distinguish between the syllables “ba” and “ga”. They noted also that the same parts of the brain were used by the infants to process sounds as adults. This, the researchers conclude, shows that linguistic connections in the brain develop before birth and because of that do not need to be acquired afterwards, suggesting that at least some abilities are innate.

The language of Jesus, close to vanishing

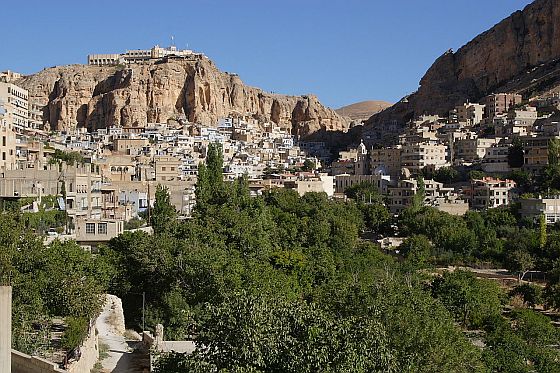

The Christian village of Maaloula, in the hills outside Damascus, Syria, the last remaining community where Aramaic is maintained as an everyday language.

Aramaic, once the common language of the entire Middle East, is one or two generations away from extinction. Ariel Sabar writes: It was a sunny morning in May, and I was in a car with a linguist and a tax preparer trolling the suburbs of Chicago for native speakers of Aramaic, the 3,000-year-old language of Jesus.

The linguist, Geoffrey Khan of the University of Cambridge, was nominally in town to give a speech at Northwestern University, in Evanston. But he had another agenda: Chicago’s northern suburbs are home to tens of thousands of Assyrians, Aramaic-speaking Christians driven from their Middle Eastern homelands by persecution and war. The Windy City is a heady place for one of the world’s foremost scholars of modern Aramaic, a man bent on documenting all of its dialects before the language — once the tongue of empires — follows its last speakers to the grave.

The tax preparer, Elias Bet-shmuel, a thickset man with a shiny pate, was a local Assyrian who had offered to be our sherpa. When he burst into the lobby of Khan’s hotel that morning, he announced the stops on our two-day trek in the confidential tone of a smuggler inventorying the contents of a shipment.

“I got Shaqlanaye, I have Bebednaye.” He was listing immigrant families by the names of the northern Iraqi villages whose dialects they spoke. Several of the families, it turned out, were Bet-shmuel’s clients.

As Bet-shmuel threaded his Infiniti sedan toward the nearby town of Niles, Illinois, Khan, a rangy 55-year-old, said he was on safari for speakers of “pure” dialects: Aramaic as preserved in villages, before speakers left for big, polyglot cities or, worse, new countries. This usually meant elderly folk who had lived the better part of their lives in mountain enclaves in Iraq, Syria, Iran or Turkey. “The less education the better,” Khan said. “When people come together in towns, even in Chicago, the dialects get mixed. When people get married, the husband’s and wife’s dialects converge.”

We turned onto a grid of neighborhood streets, and Bet-shmuel announced the day’s first stop: a 70-year-old widow from Bebede who had come to Chicago just a decade earlier. “She is a housewife with an elementary education. No English.”

Khan beamed. “I fall in love with these old ladies,” he said.

Aramaic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew and Arabic, was the common tongue of the entire Middle East when the Middle East was the crossroads of the world. People used it for commerce and government across territory stretching from Egypt and the Holy Land to India and China. Parts of the Bible and the Jewish Talmud were written in it; the original “writing on the wall,” presaging the fall of the Babylonians, was composed in it. As Jesus died on the cross, he cried in Aramaic, “Elahi, Elahi, lema shabaqtani?” (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”)

But Aramaic is down now to its last generation or two of speakers, most of them scattered over the past century from homelands where their language once flourished. In their new lands, few children and even fewer grandchildren learn it. (My father, a Jew born in Kurdish Iraq, is a native speaker and scholar of Aramaic; I grew up in Los Angeles and know just a few words.) This generational rupture marks a language’s last days. For field linguists like Khan, recording native speakers — “informants,” in the lingo — is both an act of cultural preservation and an investigation into how ancient languages shift and splinter over time.

In a highly connected global age, languages are in die-off. Fifty to 90 percent of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken today are expected to go silent by century’s end. We live under an oligarchy of English and Mandarin and Spanish, in which 94 percent of the world’s population speaks 6 percent of its languages. Yet among threatened languages, Aramaic stands out. Arguably no other still-spoken language has fallen farther. [Continue reading…]

Dolphins may call each other by name

Wired: What might dolphins be saying with all those clicks and squeaks? Each other’s names, suggests a new study of the so-called signature whistles that dolphins use to identify themselves.

Whether the vocalizations should truly be considered names, and whether dolphins call to compatriots in a human-like manner, is contested among scientists, but the results reinforce the possibility. After all, to borrow the argot of animal behavior studies, people often greet friends by copying their individually distinctive vocal signatures.

“They use these when they want to reunite with a specific individual,” said biologist Stephanie King of Scotland’s University of St. Andrews. “It’s a friendly, affiliative sign.”

In their new study, published Feb. 19 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, King and fellow St. Andrews biologist Vincent Janik investigate a phenomenon they first described in 2006: bottlenose dolphins recognizing the signature whistles of other dolphins they know.

Signature whistles are taught to dolphins by their mothers, and the results were soon popularized as evidence of dolphin names. Many questions remained, though, about the whistles’ function, and in particular about the tendency of dolphins to copy each others’ signatures.

Were they simply challenging each other, like birds matching each other’s songs in displays of territorial aggression? Or using the copied signals deceptively, perhaps allowing males to court females guarded by other males? Or was a more information-rich exchange occurring, a back-and-forth between animals who knew each other and were engaging in something like a dialog?

To investigate these possibilities, King and Janik’s team analyzed recordings made over several decades by the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, a Florida-based monitoring project in which pairs of dolphins are captured and held in separate nets for a few hours as researchers photograph and study them.

During the captures, the dolphins can’t see each other, but can hear each other and continue to communicate. In their analysis, King and Janik showed that some of the communications are copies of captured compatriots’ signature whistles — and, crucially, that the dolphins most likely to make these were mothers and calves or closely allied males.

They seemed to be using the whistles to keep in touch with the dolphins they knew best, just as two friends might if suddenly and unexpectedly separated while walking down a street. Moreover, copying wasn’t exact, but involved modulations at the beginning and end of each call, perhaps allowing dolphins to communicate additional information, such as the copier’s own identity.

That possibility hints at what linguists call referential communication with learned signals, or the use of learned rather than instinctively understood sounds to mentally represent other objects and individuals. As of now, only humans are known to do this naturally. [Continue reading…]

The reluctance to posit human traits in animals — for fear that one might be anthropomorphizing what are intrinsically non-human behaviors — is itself the expression of a prevailing anthropocentric superstition: that human beings are fundamentally different from all other animals.

When it comes to discerning human-like communication in non-human species there is an additional bias: scientific researchers tend to over-emphasize the function language has as a system of symbolic representation and understate its importance as a means for engaging in emotional exchanges.

Even though our understanding of dolphin communication is very rudimentary, I’d be inclined to believe not only that dolphins do call each other by name, but that they are also keenly attuned and adept in the combination of name and tone.

After all, the utterance of an individual’s name generally signifies much less than the way the name is called — unless that is one is sitting in a waiting room and being hailed by a nameless official. Lucky for dolphins their exchanges never need to be straight-jacketed like that.

How languages shape our understanding of the world

Pormpuraaw, Queensland, Australia

There are currently about 7,000 languages spoken around the world. It is estimated that by the end of this century as many as 90% of them will have become extinct.

Some people might think that the fewer languages there are spoken, the more readily people will understand each other and that ideally we should all speak the same language. The divisions of Babel would be gone. But as rational as this perspective might sound, it overlooks the degree to which humanity is further impoverished each time a language is lost — each time a unique way of seeing the world vanishes.

To understand the value of language diversity it’s necessary to recognize the ways in which each language serves as a radically different prism through which its speakers engage with life.

Lera Boroditsky, an assistant professor of psychology at Stanford, talks about how the languages we speak, shape the way we think. The excerpt below comes a video presentation which can be viewed at John Brockman’s Edge:

Let me give you three of my favorite examples on how speakers of different languages think differently in important ways. I’m going to give you an example from space; how people navigate in space. That ties into how we think about time as well. Second, I’m going to give you an example on color; how we are able to discriminate colors. Lastly, I’m going to give you an example on grammatical gender; how we’re able to discriminate objects. And I might throw in an extra example on causality.

Let’s start with one of my favorite examples, this comes from the work of Steve Levinson and John Haviland, who first started describing languages that have the following amazing property: there are some languages that don’t use words like “left” and “right.” Instead, everything in the language is laid out in absolute space. That means you have to say things like, “There is an ant on your northwest leg,” Or “can you move the cup to the south southeast a little bit?” Now to speak a language like this, you have to stay oriented. You have to always know which way you’re facing. And it’s not just that you have to stay oriented in the moment, all your memories of your past have to be oriented as well, so that you can say things like “Oh, I must have left my glasses to the southwest of the telephone.” That is a memory that you have to be able to generate. You have to have represented your experience in absolute space with cardinal directions.

What Steve Levinson and John Haviland found is that folks who speak languages like this indeed stay oriented remarkably well. There are languages like this around the world; they’re in Australia, they’re in China, they’re in South America. Folks who speak these languages, even young kids, are able to orient really well.

I had the opportunity to work with a group like this in Australia in collaboration with Alice Gaby. This was an Aboriginal group, the Kuuk Thaayorre. One of my first experiences there was standing next to a five year old girl. I asked her the same question that I’ve asked many eminent scientists and professors, rooms full of scholars in America. I ask everyone, “Close your eyes, and now point southeast.” When I ask people to do this, usually they laugh because they think, “well, that’s a silly question. How am I supposed to know that?” Often a lot of people refuse to point. They don’t know which way it is. When people do point, it takes a while, and they point in every possible direction. I usually don’t know which way southeast is myself, but that doesn’t preclude me from knowing that not all of the possible given answers are correct, because people point in every possible direction.

But here I am standing next to a five year old girl in Pormpuraaw, in this Aboriginal community, and I ask for her to point southeast, and she’s able to do it without hesitation, and she’s able to do it correctly. That’s the case for people who live in this community generally. That’s just a normal thing to be able to do. I had to take out a compass to make sure that she was correct, because I couldn’t remember. [Continue reading…]