Vasant Dhar writes: Remember Watson, IBM’s Jeopardy champion? A couple years ago, Watson beat the top two human champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter at a game where even interpreting the cue is complex with language nuances. Not to mention finding answers at lightning speed on any subject matter.

Yet after the initial excitement, most people (except for a notable few) forgot about Watson. But we need to pay attention, and now. Because Watson heralds the emergence of “thinking machines” capable of knowledge creation that will trump today’s knowledge retrieval machines. And this could be the beginning of a serious challenge to Google, whose most ambitious initiatives — from wearables to cars to aging — are funded through its thriving advertising business.

Watson was arguably the first computer ever to pass the “Turing Test,” a test designed by British mathematician Alan Turing, to determine whether a computer could think. Turing argued that it was too hard to define “thinking,” but a computer could be considered “intelligent” if a human interlocutor is unable to distinguish which of two entities being questioned is a machine and which is a human.

If you had a choice between asking a question to a Jeopardy champion and a search engine, which would you choose; that is, who has the upper hand — Watson or PageRank? One obvious answer is that it depends on what people value more: retrieving information or solving problems. But information retrieval is part of problem solving. If IBM did search, Watson would do much better than Google on the tough problems, and they could still resort to a simple PageRank-like algorithm as a last resort. Which means there would be no reason for anyone to start their searches on Google. All the search traffic that makes Google seemingly invincible now could begin to shrink over time.

To put this in perspective: We were pleasantly surprised when the computer returned anything even remotely related to what we wanted when we typed a query into search engines like Altavista, Lycos, or Excite. But that was because our expectations for computers were very low back in the 1990s. When Google came along with its PageRank algorithm for gauging relevance of a free-form text query to web pages, it cornered the search market.

Today, more than 90 percent of Google’s current revenues are from sponsored search. Advertisers want to be where people search.

Google continues to top the search game with the mission of “organiz[ing] the world’s information and mak[ing] it universally accessible and useful.” But this mission is limited given how rapidly artificial intelligence has pushed the boundaries of what’s possible (Siri is just one such instance): It’s raised expectations of what we expect from computers. In this new mindset, Google is basically a gigantic database with rich access and retrieval mechanisms without the ability to create new knowledge. The company may have embellished PageRank with “semantic” knowledge that enables it to return incrementally better results — but it cannot solve problems.

But Watson can. It can solve problems through its ability to reason about its store of information, and it can do it by conversing with people in natural language. It can create new knowledge from the ever-increasing store of human and computer-generated information on the Internet.

In other words: Google can retrieve, but Watson can create. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Science/Technology

For scientists in a democracy, to dissent is to be reasonable

George Monbiot writes: It’s as clear and chilling a statement of intent as you’re likely to read. Scientists should be “the voice of reason, rather than dissent, in the public arena”. Vladimir Putin? Kim Jong-un? No, Professor Ian Boyd, chief scientific adviser at the UK’s Department for Environment.

Boyd’s doctrine is a neat distillation of government policy in Britain, Canada and Australia. These governments have suppressed or misrepresented inconvenient findings on climate change, pollution, pesticides, fisheries and wildlife. They have shut down programmes that produce unwelcome findings and sought to muzzle scientists. This is a modern version of Soviet Lysenkoism: crushing academic dissent on behalf of bad science and corporate power.

Writing in an online journal, Boyd argued that if scientists speak freely, they create conflict between themselves and policymakers, leading to a “chronically deep-seated mistrust of scientists that can undermine the delicate foundation upon which science builds relevance”. This, in turn, “could set back the cause of science in government”. So they should avoid “suggesting that policies are either right or wrong”. If they must speak out, they should do so through “embedded advisers (such as myself), and by being the voice of reason, rather than dissent, in the public arena”.

Shut up, speak through me, don’t dissent – or your behaviour will ensure that science becomes irrelevant. Note that the conflicts between science and policy are caused by scientists, rather than by politicians ignoring or abusing the evidence. Or by chief scientific advisers. [Continue reading…]

The banality of ‘don’t be evil’

Julian Assange writes: “The New Digital Age” is a startlingly clear and provocative blueprint for technocratic imperialism, from two of its leading witch doctors, Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen, who construct a new idiom for United States global power in the 21st century. This idiom reflects the ever closer union between the State Department and Silicon Valley, as personified by Mr. Schmidt, the executive chairman of Google, and Mr. Cohen, a former adviser to Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton who is now director of Google Ideas.

The authors met in occupied Baghdad in 2009, when the book was conceived. Strolling among the ruins, the two became excited that consumer technology was transforming a society flattened by United States military occupation. They decided the tech industry could be a powerful agent of American foreign policy.

The book proselytizes the role of technology in reshaping the world’s people and nations into likenesses of the world’s dominant superpower, whether they want to be reshaped or not. The prose is terse, the argument confident and the wisdom — banal. But this isn’t a book designed to be read. It is a major declaration designed to foster alliances.

“The New Digital Age” is, beyond anything else, an attempt by Google to position itself as America’s geopolitical visionary — the one company that can answer the question “Where should America go?” It is not surprising that a respectable cast of the world’s most famous warmongers has been trotted out to give its stamp of approval to this enticement to Western soft power. The acknowledgments give pride of place to Henry Kissinger, who along with Tony Blair and the former C.I.A. director Michael Hayden provided advance praise for the book.

In the book the authors happily take up the white geek’s burden. A liberal sprinkling of convenient, hypothetical dark-skinned worthies appear: Congolese fisherwomen, graphic designers in Botswana, anticorruption activists in San Salvador and illiterate Masai cattle herders in the Serengeti are all obediently summoned to demonstrate the progressive properties of Google phones jacked into the informational supply chain of the Western empire. [Continue reading…]

A new theory of everything

New Scientist: Physicists have a problem, and they will be the first to admit it. The two mathematical frameworks that govern modern physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, just don’t play nicely together despite decades of attempts at unification. Eric Weinstein, a consultant at a New York City hedge fund with a background in mathematics and physics, says the solution is to find beauty before seeking truth.

Weinstein hit the headlines last week after mathematician Marcus du Sautoy at the University of Oxford invited him to give a lecture detailing his new theory of the universe, dubbed Geometric Unity. Du Sautoy also provided an overview of Weinstein’s theory on the website of The Guardian newspaper to “promote, perhaps, a new way of doing science”.

For a number of reasons, few physicists attended Weinstein’s initial lecture, and with no published equations to review, the highly public airing of his theory has generated heated controversy. Today, Weinstein attempted to rectify the situation by repeating his lecture at Oxford. This time a number of physicists were in the lecture hall. Most remain doubtful.

Most physicists working on unification are trying to create a quantum version of general relativity, informed by the list of particles in the standard model of physics. Weinstein believes we should instead start with the basic geometric tools of general relativity and work at extending the equations in mathematically natural ways, without worrying whether they fit with the observable universe. Once you have such equations in hand, you can try to match them up with reality. [Continue reading…]

James Lovelock: A man for all seasons

John Gray writes: A resolute independence has shaped James Lovelock’s life as a scientist. On the occasions over the past decade or so when I visited him at his home in a remote and wooded part of Devon to discuss his work and share our thoughts, I found him equipped with a mass of books and papers and a small outhouse where he was able to perform experiments and devise the inventions that have supported him through much of his long career. That is all he needed to carry on his work as an independent scientist. Small but sturdily built, often laughing, animated and highly sociable, he is, at the age of 93, far from being any kind of recluse. But he has always resisted every kind of groupthink, and followed his own line of inquiry.

At certain points in his life Lovelock worked in large organisations. In 1941, he took up a post as a junior scientist at the National In – stitute for Medical Research, an offshoot of the Medical Research Council, and in 1961 he was invited to America to join a group of scientists interested in exploring the moon who were based at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa). It was during his time at Nasa that Lovelock had the first inklings of what would become the Gaia theory – according to which the earth is a planet that behaves like a living being, controlling its surface and atmosphere to keep the environment hospitable to life. He has since worked closely with other scientists, including his former doctoral student Andrew Watson, who is now a professor of environmental science, and the late American microbiologist Lynn Margulis, in developing the theory.

Lovelock has always cherished the freedom to follow his own ideas and stood aside from institutions in which science is conducted as a vast collective enterprise. Partly this is an expression of his ingrained individualism, but it also reflects his radically empiricist view of science as a direct engagement with the world and his abiding mistrust of consensual thinking. In these and other respects, he has more in common with thinkers such as Darwin and Einstein, who were able to transform our view of the world because they did not work under any kind of external direction, than he does with most of the scientists who are at work today. [Continue reading…]

Technology without borders

The Washington Post reports: Measured in millimeters, the tiny device was designed to allow drones, missiles and rockets to hit targets without satellite guidance. An advanced version was being developed secretly for the U.S. military by a small company and L-3 Communications, a major defense contractor.

On Monday, Sixing Liu, a Chinese citizen who worked at L-3’s space and navigation division, was sentenced in federal court here to five years and 10 months for taking thousands of files about the device, called a disk resonator gyroscope, and other defense systems to China in violation of a U.S. arms embargo.

The case illustrates what the FBI calls a growing “insider threat” that hasn’t drawn as much attention as Chinese cyber operations. But U.S. authorities warned that this type of espionage can be just as damaging to national security and American business.

“The reason this technology is on the State Department munitions list, and controlled . . . is it can navigate, control and position missiles, aircraft, drones, bombs, lasers and targets very accurately,” said David Smukowski, president of Sensors in Motion, the small company in Bellvue, Wash., developing the technology with L-3. “While it saves lives, it can also be very strategic. It is rocket science.”

Smukowski estimated that the loss of this tiny piece of technology alone could ultimately cost the U.S. military hundreds of millions of dollars. [Continue reading…]

A new view of the universe

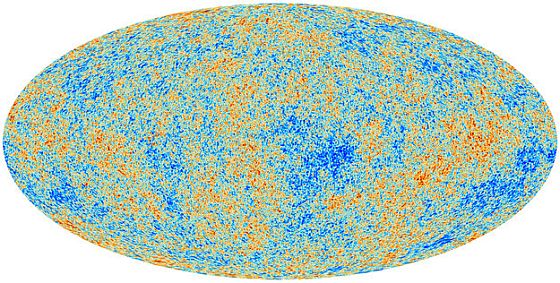

Slate: The Universe is a wee bit older than we thought. Not only that, but turns out the ingredients are a little bit different, too. And not only that, but the way they’re mixed isn’t quite what we expected, either. And not only that, but there are hints and whispers of something much grander going on as well.

So what’s going on?

The European Space Agency’s Planck mission is what’s going on. Planck has been scanning the entire sky, over and over, peering at the radio and microwaves pouring out of the Universe. Some of this light comes from stars, some from cold clumps of dust, some from exploding stars and galaxies. But a portion of it comes from farther away… much farther away. Billions of light years, in fact, all the way from the edge of the observable Universe.

This light was first emitted when the Universe was very young, about 380,000 years old. It was blindingly bright, but in its eons-long travel to us has dimmed and reddened. Fighting the expansion of the Universe itself, the light has had its wavelength stretched out until it gets to us in the form of microwaves. Planck gathered that light for over 15 months, using instruments far more sensitive than ever before.

The light from the early Universe shows it’s not smooth. If you crank the contrast way up you see slightly brighter and slightly dimmer spots. These correspond to changes in temperature of the Universe on a scale of 1 part in 100,000. That’s incredibly small, but has profound implications. We think those fluctuations were imprinted on the Universe when it was only a trillionth of a trillionth of a second old, and they grew with the Universe as it expanded. They were also the seeds of the galaxies and the clusters and galaxies we see today.

What started out as quantum fluctuations when the Universe was smaller than a proton have now grown to be the largest structures in the cosmos, hundreds of millions of light years across. Let that settle in your brain a moment. [Continue reading…]

Searching for a smartphone not soaked in blood

George Monbiot writes: If you are too well connected, you stop thinking. The clamour, the immediacy, the tendency to absorb other people’s thoughts, interrupt the deep abstraction required to find your own way. This is one of the reasons why I have not yet bought a smartphone. But the technology is becoming ever harder to resist. Perhaps this year I will have to succumb. So I have asked a simple question: can I buy an ethical smartphone?

There are dozens of issues, such as starvation wages, bullying, abuse and 60-hour weeks in the sweatshops manufacturing them, the debt bondage into which some of the workers are pressed, the energy used, the hazardous waste produced. But I will concentrate on just one: are the components soaked in the blood of people from the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo? For 17 years, rival armies and militias have been fighting over the region’s minerals. Among them are metals critical to the manufacture of electronic gadgets, without which no smartphone would exist: tantalum, tungsten, tin and gold.

While these elements are by no means the only reason for conflict there, they help to fund it, supporting a fragmented war that – through direct killings, displacement, disease and malnutrition – has now killed several million people. Rival armies have forced local people to dig in extremely dangerous conditions, have extorted minerals and money from self-employed miners, have tortured, mutilated and murdered those who don’t comply, and have spread terror and violence – including gang rape and child abduction – through the rest of the population. I do not want to participate. [Continue reading…]

Higgs ‘God’ particle a big let-down say physicists

Reuters reports: Scientists’ hopes that last summer’s triumphant trapping of the particle that shaped the post-Big Bang universe would quickly open the way into exotic new realms of physics like string theory and new dimensions have faded this past week.

Five days of presentations on the particle, the Higgs boson, at a scientific conference high in the Italian Alps point to it being the last missing piece in a 30-year-old cosmic blueprint and nothing more, physicists following the event say.

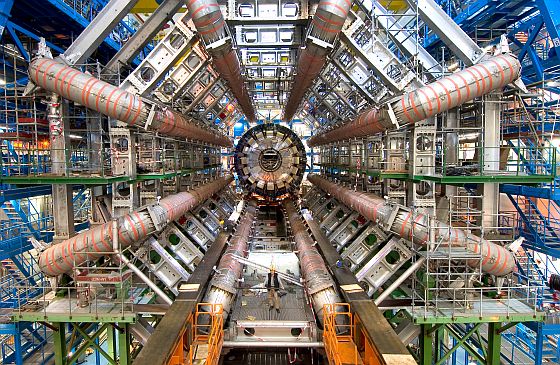

“The chances are getting slimmer and slimmer that we are going to see something else exciting anytime soon,” said physicist Pauline Gagnon from CERN near Geneva in whose Large Hadron Collider (LHC) the long-sought particle was found.

And U.S. scientist Peter Woit said in his blog that the particle was looking “very much like a garden variety SM (Standard Model) Higgs”, discouraging for researchers who were hoping for glimpses of breathtaking vistas beyond.

That conclusion, shared among analysts of vast volumes of data gathered in the LHC over the past three years, would push to well beyond 2015 any chance of sighting exotica like dark matter or super symmetric particles in the giant machine.

That is when the LHC, where particles are smashed together at light speed to create billions of mini-Big Bangs that are traced in vast detectors, resumes operation with its power doubled after a two-year shutdown from last month.

The Higgs – still not claimed as a scientific discovery because its exact nature has yet to be established – was postulated in the early 1960s as the element that gave mass to flying matter after the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago.

It was incorporated tentatively into the Standard Model when that was compiled in the 1980s, and its discovery in the LHC effectively completed that blueprint. But there are mysteries of the universe, like gravity, that remain outside it.

Some physicists have been hoping that the particle as finally found would be something beyond a “Standard Model Higgs” – offering a passage onwards into a science fiction world of “New Physics” and a zoo of new particles.

Google Glass — the next Segway to rock the world?

Since American culture measures success in dollars and since Silicon Valley leads the world in technological innovation, the industry’s leaders have a rarely questioned status as not only the richest but also the smartest entrepreneurs in the world. As co-founder of the $250 billion search giant Google, the 39 year-old Sergey Brin surely ranks as a visionary promoting a revolutionary new product: Google Glass. Or maybe not.

In terms of commercial aspirations, Brin’s TED marketing pitch made it clear that Google hopes to leapfrog over Apple by creating a device that ends up replacing the cell phone — that’s no small ambition given that cell phones have penetrated global markets more deeply than any other technology ever created. But for someone with this kind of megalomania, it was amazing to see that Brin could be so dumb as to alienate half the world by saying that cell phone use is “emasculating.”

As Wharton business ethics professor Andrea Matwyshyn noted: “a marketing strategy that positions Google Glass as a ‘man gadget’ potentially alienates half of the consumer base who might have been keenly interested in purchasing the product in the future.”

Even if the product’s marketers manage to recover from this misstep, there’s a more fundamental problem they face: whether worn by men or women, Glass is inherently a socially dysfunctional device.

Wearing this thing is a sure way to alienate yourself from everyone around you (unless you happen to be part of Google’s product development team) as Mark Hurst explains:

The key experiential question of Google Glass isn’t what it’s like to wear them, it’s what it’s like to be around someone else who’s wearing them. I’ll give an easy example. Your one-on-one conversation with someone wearing Google Glass is likely to be annoying, because you’ll suspect that you don’t have their undivided attention. And you can’t comfortably ask them to take the glasses off (especially when, inevitably, the device is integrated into prescription lenses). Finally – here’s where the problems really start – you don’t know if they’re taking a video of you.

Now pretend you don’t know a single person who wears Google Glass… and take a walk outside. Anywhere you go in public – any store, any sidewalk, any bus or subway – you’re liable to be recorded: audio and video. Fifty people on the bus might be Glassless, but if a single person wearing Glass gets on, you – and all 49 other passengers – could be recorded. Not just for a temporary throwaway video buffer, like a security camera, but recorded, stored permanently, and shared to the world.

Now, I know the response: “I’m recorded by security cameras all day, it doesn’t bother me, what’s the difference?” Hear me out – I’m not done. What makes Glass so unique is that it’s a Google project. And Google has the capacity to combine Glass with other technologies it owns.

First, take the video feeds from every Google Glass headset, worn by users worldwide. Regardless of whether video is only recorded temporarily, as in the first version of Glass, or always-on, as is certainly possible in future versions, the video all streams into Google’s own cloud of servers.

And Hurst goes on to illustrate the cascade of privacy pitfalls that will ensue.

So how world-shaking will the consumer release of Google Glass become as it rolls out later this year?

Remember what these breathless predictions were about?

“Cities will be built around this device,” predicted Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. “As big a deal as the PC, said Steve Jobs; maybe bigger than the Internet, said John Doerr, the venture capitalist behind Netscape, Amazon”.

That was before the owner of the revolutionary two-wheeled vehicle, Jimi Heselden, met an untimely death after driving over a cliff on his own Segway.

How many road accidents or fatalities will there be before Google Glass gains a reputation for not only undermining relationships but also posing a threat to life?

The perils of perfection

Evgeny Morozov: “When your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting” is the reassuring slogan greeting visitors at the Web site for LivesOn, a soon-to-launch service that promises to tweet on your behalf even after you die. By analyzing your earlier tweets, the service would learn “about your likes, tastes, syntax” and add a personal touch to all those automatically composed scribblings from the world beyond.

LivesOn may yet prove to be a parody, or it may fizzle for any number of reasons, but as an idea it highlights the dominant ideology of Silicon Valley today: what could be disrupted should be disrupted — even death.

Barriers and constraints — anything that imposes artificial limits on the human condition — are being destroyed with particular gusto. Superhuman, another mysterious start-up that could enliven any comedy show, promises to offer, as its co-founder recently put it, an unspecified service that “helps people be superhuman.” Well, at least they had the decency not to call it The Übermensch.

Recent debates about Twitter revolutions or the Internet’s impact on cognition have mostly glossed over the fact that Silicon Valley’s technophilic gurus and futurists have embarked on a quest to develop the ultimate patch to the nasty bugs of humanity. If they have their way, no individual foibles would go unpunished — ideally, technology would even make such foibles obsolete.

Even boredom seems to be in its last throes: designers in Japan have found a way to make our train trips perpetually fun-filled. With the help of an iPhone, a projector, a GPS module and Microsoft’s Kinect motion sensor, their contrivance allows riders to add new objects to what they see “outside,” thus enlivening the bleak landscape in their train windows. This could be a big hit in North Korea — and not just on trains.

Or, if you tend to forget things, Silicon Valley wants to give you an app to remember everything. If you occasionally prevaricate in order to meet your clashing obligations as a parent, friend or colleague, another app might spot inconsistencies in your behavior and inform your interlocutors if you are telling the truth. If you experience discomfort because you encounter people and things that you do not like, another app or gadget might spare you the pain by rendering them invisible.

Sunny, smooth, clean: with Silicon Valley at the helm, our life will become one long California highway. [Continue reading…]

Easier isn’t better

Google co-founder Sergey Brin accessorized with augmented-reality headset.

Google co-founder Sergey Brin recently showed off Google Glass, the company’s hands-free, voice-activated augmented-reality headset.

TED Blog: To take a picture while you’re wearing Glass, say “take picture.” Done.

“When we started Google 15 years ago,” Brin says, “my vision was that information would come to you as you need it. You wouldn’t have to search query at all.” But for now, we get information by disconnecting from other people, looking down into our smartphone. Brin asks: “Is this the way you’re meant to interact with other people?” Is the future of connection just people walking around hunched up, looking down, rubbing a featureless piece of glass? In an intimate moment, he says, “It’s kind of emasculating. Is this what you’re meant to do with your body?”

Working on this project, Brin says, was revealing: “I have a nervous tic. The cell phone is a nervous habit — If I smoked, I’d probably smoke instead, It’d look cooler. But I whip this out and look as if I have something important to do. It really opened my eyes to how much of my life I spent secluding myself away in email.”

Emasculating? That’s a telling choice of word coming from one of the leaders of the boys world of Silicon Valley.

Are people meant to interact with each other through handheld devices, Brin asks. That sounds like a reasonable question — but not if the answer is that we’d be better off using devices attached to our heads.

Brin might be able to strike a manly cyborg pose, but just as I prefer not to talk to people who hide behind dark glasses, I would find it hard to fully engage with someone whose attention is simultaneously being drawn to passing digital interlopers.

“He doesn’t seem to be all here,” used to be a way of describing loss of sanity. Now it’s the new normal, thanks to the ever-expanding means through which we can conjure illusions of connection.

Presumably Google hopes that in its pursuit of world domination, Google Glass will be the tool that allows the search giant to leap ahead of Apple as their arch rival remains trapped in the emasculating world of handheld devices.

No doubt smartphones separate individuals from the people around them by providing access to a social world untethered from space and time. But the separation results from being disembodied — not because the vehicle of disembodiment is attached to the hand instead of the head.

At the same time, behind this innovation — like so many other purported advances — there is a false governing premise: easier is better.

The smarter Google gets, the dumber we become.

This isn’t just a Luddite sentiment; it’s what Google itself has discovered. Google learns how to improve its search algorithms by studying the way people use its software, but it turns out that this creates a kind of negative feedback loop. The better Google becomes in figuring out what people are looking for, the clumsier people become in framing their questions.

Tim Adams talked to Amit Singhal, head of Google Search, who described how Google can learn from user behavior and infer the quality of search results based on the speed and frequency with which a user returns to a search results page.

I imagine, I say, that along the way he has been assisted in this work by the human component. Presumably we have got more precise in our search terms the more we have used Google?

He sighs, somewhat wearily. “Actually,” he says, “it works the other way. The more accurate the machine gets, the lazier the questions become.”

Is smart making us dumb?

Evgeny Morozov writes: Would you like all of your Facebook FB -0.56% friends to sift through your trash? A group of designers from Britain and Germany think that you might. Meet BinCam: a “smart” trash bin that aims to revolutionize the recycling process.

BinCam looks just like your average trash bin, but with a twist: Its upper lid is equipped with a smartphone that snaps a photo every time the lid is shut. The photo is then uploaded to Mechanical Turk, the Amazon-run service that lets freelancers perform laborious tasks for money. In this case, they analyze the photo and decide if your recycling habits conform with the gospel of green living. Eventually, the photo appears on your Facebook page.

You are also assigned points, as in a game, based on how well you are meeting the recycling challenge. The household that earns the most points “wins.” In the words of its young techie creators, BinCam is designed “to increase individuals’ awareness of their food waste and recycling behavior,” in the hope of changing their habits.

BinCam has been made possible by the convergence of two trends that will profoundly reshape the world around us. First, thanks to the proliferation of cheap, powerful sensors, the most commonplace objects can finally understand what we do with them—from umbrellas that know it’s going to rain to shoes that know they’re wearing out—and alert us to potential problems and programmed priorities. These objects are no longer just dumb, passive matter. With some help from crowdsourcing or artificial intelligence, they can be taught to distinguish between responsible and irresponsible behavior (between recycling and throwing stuff away, for example) and then punish or reward us accordingly — in real time.

And because our personal identities are now so firmly pegged to our profiles on social networks such as Facebook and Google, our every interaction with such objects can be made “social”—that is, visible to our friends. This visibility, in turn, allows designers to tap into peer pressure: Recycle and impress your friends, or don’t recycle and risk incurring their wrath.

These two features are the essential ingredients of a new breed of so-called smart technologies, which are taking aim at their dumber alternatives. Some of these technologies are already catching on and seem relatively harmless, even if not particularly revolutionary: smart watches that pulsate when you get a new Facebook poke; smart scales that share your weight with your Twitter followers, helping you to stick to a diet; or smart pill bottles that ping you and your doctor to say how much of your prescribed medication remains.

But many smart technologies are heading in another, more disturbing direction. A number of thinkers in Silicon Valley see these technologies as a way not just to give consumers new products that they want but to push them to behave better. Sometimes this will be a nudge; sometimes it will be a shove. But the central idea is clear: social engineering disguised as product engineering.

In 2010, Google Chief Financial Officer Patrick Pichette told an Australian news program that his company “is really an engineering company, with all these computer scientists that see the world as a completely broken place.” Just last week in Singapore, he restated Google’s notion that the world is a “broken” place whose problems, from traffic jams to inconvenient shopping experiences to excessive energy use, can be solved by technology. The futurist and game designer Jane McGonigal, a favorite of the TED crowd, also likes to talk about how “reality is broken” but can be fixed by making the real world more like a videogame, with points for doing good. From smart cars to smart glasses, “smart” is Silicon Valley’s shorthand for transforming present-day social reality and the hapless souls who inhabit it. [Continue reading…]

A cyborg who sees color through sound

Long before the term cyborg had been coined, Henry David Thoreau — who saw few if any advances in our inexorable movement away from our natural condition — declared: “men have become the tool of their tools.”

Creating the means for someone with total color blindness to be able to hear color, seems like an amazing idea, but we glimpse the dystopian potential of such technology when the beneficiary says the sounds coming from the strident colors of cleaning products displayed on the aisle of a supermarket are more enjoyable than the sound-color of the ocean.

Singularity Hub: What would your world be like if you couldn’t see color? For artist Neil Harbisson, a rare condition known as achromatopsia that made him completely color blind rendered that question meaningless. Not being able to see color at all meant that there was no blue in the sky or green in grass, and these descriptions were merely something to be taken on faith or memorized to get the correct answers in school.

But Neil’s life would change drastically when he met computer scientist Adam Montandon and with help from a few others, they developed the eyeborg, an electronic eye that transforms colors into sounds. Colors became meaningful for Neil in an experiential way, but one that was fundamentally different than how others described them.

This augmentation device wasn’t like a set of headphones that he could put on when he wanted to “listen” to the world around him, but became a permanent part of who he was. Though he had to memorize how the sounds corresponded to certain colors, in time the sounds became part of his perception and the way he “sees” the world. He even started to expand the range of what he could “see”, so that wavelengths of light outside of the visible range could be perceived.

In other words, he became cybernetic…

Neil boldly paints a picture of what the future holds where augmentation devices will alter how we experience the world. Whether for corrective or elective motives, people will someday adopt these technologies routinely, perhaps choosing artificial synesthesia as a means of seeing the world in a broader or deeper way.

In color theory, color is described in terms of three attributes: hue, saturation, and value. Hue is what we generally refer to with color terms — red, green, purple etc. Saturation is the intensity of a color — pale yellow, for instance, has less saturation than lemon yellow. And value refers to the lightness or darkness of a color. In moonlight, all we can perceive is color value, without any ability to register hues or saturation.

When color is understood in these terms, achromatopsia does not have to be viewed as a lack of color vision since, at least in some cases, it can actually lead to the experience of a refinement of sight.

As much as Neil Harbisson might feel that technology has enhanced his perception of the world, I find it depressing that anyone would fail to see that in order to value this kind of nominal extension of the senses requires first that we underestimate the subtlety of human perception.

In An Anthropologist On Mars, Oliver Sacks describes the experience of Jonathan I., a 65-year old artist who suddenly lost his color vision as a result of concussion sustained in a car accident.

As an artist, the loss was devastating.

He knew the colors of everything, with an extraordinary exactness (he could give not only the names but the numbers of colors as these were listed in a Pantone chart of hues he had used for many years). He could identify the green of van Gogh’s billiard table in this way unhesitatingly. He knew all the colors in his favorite paintings, but could no longer see them, either when he looked or in his mind’s eye…

As the months went by, he particularly missed the brilliant colors of spring — he had always loved flowers, but now he could only distinguish them by shape or smell. The blue jays were brilliant no longer, — their blue, curiously, was now seen as pale grey. He could no longer see the clouds in the sky, their whiteness, or off-whiteness as he saw them, being scarcely distinguishable from the azure, which seemed bleached to a pale grey…

His initial sense of helplessness started to give way to a sense of resolution — he would paint in black and white, if he could not paint in color; he would try to live in a black-and-white world as fully as he could. This resolution was strengthened by a singular experience, about five weeks after his accident, as he was driving to the studio one morning. He saw the sunrise over the highway, the blazing reds all turned into black: “The sun rose like a bomb, like some enormous nuclear explosion”, he said later. “Had anyone ever seen a sunrise in this way before?”

Inspired by the sunrise, he started painting again—he started, indeed, with a black-and-white painting that he called Nuclear Sunrise, and then went on to the abstracts he favored, but now painting in black and white only. The fear of blindness continued to haunt him but, creatively transmuted, shaped the first “real” paintings he did after his color experiments. Black-and-white paintings he now found he could do, and do very well. He found his only solace working in the studio, and he worked fifteen, even eighteen, hours a day. This meant for him a kind of artistic survival: “I felt if I couldn’t go on painting”, he said later, “I wouldn’t want to go on at all.”…

Color perception had been an essential part not only of Mr. I.’s visual sense, but his aesthetic sense, his sensibility, his creative identity, an essential part of the way he constructed his world — and now color was gone, not only in perception, but in imagination and memory as well. The resonances of this were very deep. At first he was intensely, furiously conscious of what he had lost (though “conscious”, so to speak, in the manner of an amnesiac). He would glare at an orange in a state of rage, trying to force it to resume its true color. He would sit for hours before his (to him) dark grey lawn, trying to see it, to imagine it, to remember it, as green. He found himself now not only in an impoverished world, but in an alien, incoherent, and almost nightmarish one. He expressed this soon after his injury, better than he could in words, in some of his early, desperate paintings.

But then, with the “apocalyptic” sunrise, and his painting of this, came the first hint of a change, an impulse to construct the world anew, to construct his own sensibility and identity anew. Some of this was conscious and deliberate: retraining his eyes (and hands) to operate, as he had in his first days as an artist. But much occurred below this level, at a level of neural processing not directly accessible to consciousness or control. In this sense, he started to be redefined by what had happened to him — redefined physiologically, psychologically, aesthetically — and with this there came a transformation of values, so that the total otherness, the alienness of his V1 world, which at first had such a quality of horror and nightmare, came to take on, for him, a strange fascination and beauty…

At once forgetting and turning away from color, turning away from the chromatic orientation and habits and strategies of his previous life, Mr. I., in the second year after his injury, found that he saw best in subdued light or twilight, and not in the full glare of day. Very bright light tended to dazzle and temporarily blind him — another sign of damage to his visual systems—but he found the night and nightlife peculiarly congenial, for they seemed to be “designed”, as he once said, “in terms of black and white.”

He started becoming a “night person”, in his own words, and took to exploring other cities, other places, but only at night. He would drive, at random, to Boston or Baltimore, or to small towns and villages, arriving at dusk, and then wandering about the streets for half the night, occasionally talking to a fellow walker, occasionally going into little diners: “Everything in diners is different at night, at least if it has windows. The darkness comes into the place, and no amount of light can change it. They are transformed into night places. I love the nighttime”, Mr. I. said. “Gradually I am becoming a night person. It’s a different world: there’s a lot of space — you’re not hemmed in by streets, by people — It’s a whole new world.”…

Most interesting of all, the sense of profound loss, and the sense of unpleasantness and abnormality, so severe in the first months following his head injury, seemed to disappear, or even reverse. Although Mr. I. does not deny his loss, and at some level still mourns it, he has come to feel that his vision has become “highly refined”, “privileged”, that he sees a world of pure form, uncluttered by color. Subtle textures and patterns, normally obscured for the rest of us because of their embedding in color, now stand out for him…

He feels he has been given “a whole new world”, which the rest of us, distracted by color, are insensitive to. He no longer thinks of color, pines for it, grieves its loss. He has almost come to see his achromatopsia as a strange gift, one that has ushered him into a new state of sensibility and being.

Perhaps the greatest ability we are endowed with by nature resides in none of our individual senses but in our surprising powers of adaptation.

In the current technology-worshiping milieu we are indeed becoming the tools of our tools, but in a more literal sense than Thoreau might have imagined. Unwitting slaves, chained to machines — through devices that supposedly form indispensable connections to the world we are gradually becoming disconnected from what it means to be human.

Searching for truth in a post-green world

Paul Kingsnorth writes: Etymology can be interesting. Scythe, originally rendered sithe, is an Old English word, indicating that the tool has been in use in these islands for at least a thousand years. But archaeology pushes that date much further out; Roman scythes have been found with blades nearly two meters long. Basic, curved cutting tools for use on grass date back at least ten thousand years, to the dawn of agriculture and thus to the dawn of civilizations. Like the tool, the word, too, has older origins. The Proto-Indo-European root of scythe is the word sek, meaning to cut, or to divide. Sek is also the root word of sickle, saw, schism, sex, and science.

I’VE RECENTLY BEEN reading the collected writings of Theodore Kaczynski. I’m worried that it may change my life. Some books do that, from time to time, and this is beginning to shape up as one of them.

It’s not that Kaczynski, who is a fierce, uncompromising critic of the techno-industrial system, is saying anything I haven’t heard before. I’ve heard it all before, many times. By his own admission, his arguments are not new. But the clarity with which he makes them, and his refusal to obfuscate, are refreshing. I seem to be at a point in my life where I am open to hearing this again. I don’t know quite why.

Here are the four premises with which he begins the book:

- Technological progress is carrying us to inevitable disaster.

- Only the collapse of modern technological civilization can avert disaster.

- The political left is technological society’s first line of defense against revolution.

- What is needed is a new revolutionary movement, dedicated to the elimination of technological society.

Kaczynski’s prose is sparse, and his arguments logical and unsentimental, as you might expect from a former mathematics professor with a degree from Harvard. I have a tendency toward sentimentality around these issues, so I appreciate his discipline. I’m about a third of the way through the book at the moment, and the way that the four arguments are being filled out is worryingly convincing. Maybe it’s what scientists call “confirmation bias,” but I’m finding it hard to muster good counterarguments to any of them, even the last. I say “worryingly” because I do not want to end up agreeing with Kaczynski. There are two reasons for this.

Firstly, if I do end up agreeing with him — and with other such critics I have been exploring recently, such as Jacques Ellul and D. H. Lawrence and C. S. Lewis and Ivan Illich — I am going to have to change my life in quite profound ways. Not just in the ways I’ve already changed it (getting rid of my telly, not owning a credit card, avoiding smartphones and e-readers and sat-navs, growing at least some of my own food, learning practical skills, fleeing the city, etc.), but properly, deeply. I am still embedded, at least partly because I can’t work out where to jump, or what to land on, or whether you can ever get away by jumping, or simply because I’m frightened to close my eyes and walk over the edge.

I’m writing this on a laptop computer, by the way. It has a broadband connection and all sorts of fancy capabilities I have never tried or wanted to use. I mainly use it for typing. You might think this makes me a hypocrite, and you might be right, but there is a more interesting observation you could make. This, says Kaczynski, is where we all find ourselves, until and unless we choose to break out. In his own case, he explains, he had to go through a personal psychological collapse as a young man before he could escape what he saw as his chains. He explained this in a letter in 2003:

I knew what I wanted: To go and live in some wild place. But I didn’t know how to do so. . . . I did not know even one person who would have understood why I wanted to do such a thing. So, deep in my heart, I felt convinced that I would never be able to escape from civilization. Because I found modern life absolutely unacceptable, I grew increasingly hopeless until, at the age of 24, I arrived at a kind of crisis: I felt so miserable that I didn’t care whether I lived or died. But when I reached that point a sudden change took place: I realized that if I didn’t care whether I lived or died, then I didn’t need to fear the consequences of anything I might do. Therefore I could do anything I wanted. I was free!

At the beginning of the 1970s, Kaczynski moved to a small cabin in the woods of Montana where he worked to live a self-sufficient life, without electricity, hunting and fishing and growing his own food. He lived that way for twenty-five years, trying, initially at least, to escape from civilization. But it didn’t take him long to learn that such an escape, if it were ever possible, is not possible now. More cabins were built in his woods, roads were enlarged, loggers buzzed through his forests. More planes passed overhead every year. One day, in August 1983, Kaczynski set out hiking toward his favorite wild place:

The best place, to me, was the largest remnant of this plateau that dates from the Tertiary age. It’s kind of rolling country, not flat, and when you get to the edge of it you find these ravines that cut very steeply in to cliff-like drop-offs and there was even a waterfall there. . . . That summer there were too many people around my cabin so I decided I needed some peace. I went back to the plateau and when I got there I found they had put a road right through the middle of it. . . . You just can’t imagine how upset I was. It was from that point on I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge.

I can identify with pretty much every word of this, including, sometimes, the last one. This is the other reason that I do not want to end up being convinced by Kaczynski’s position. Ted Kaczynski was known to the FBI as the Unabomber during the seventeen years in which he sent parcel bombs from his shack to those he deemed responsible for the promotion of the technological society he despises. In those two decades he killed three people and injured twenty-four others. His targets lost eyes and fingers and sometimes their lives. He nearly brought down an airplane. Unlike many other critics of the technosphere, who are busy churning out books and doing the lecture circuit and updating their anarcho-primitivist websites, Kaczynski wasn’t just theorizing about being a revolutionary. He meant it.

BACK TO THE SCYTHE. It’s an ancient piece of technology; tried and tested, improved and honed, literally and metaphorically, over centuries. It’s what the green thinkers of the 1970s used to call an “appropriate technology” — a phrase that I would love to see resurrected — and what the unjustly neglected philosopher Ivan Illich called a “tool for conviviality.” Illich’s critique of technology, like Kaczynski’s, was really a critique of power. Advanced technologies, he explained, created dependency; they took tools and processes out of the hands of individuals and put them into the metaphorical hands of organizations. The result was often “modernized poverty,” in which human individuals became the equivalent of parts in a machine rather than the owners and users of a tool. In exchange for flashing lights and throbbing engines, they lost the things that should be most valuable to a human individual: Autonomy. Freedom. Control.

Illich’s critique did not, of course, just apply to technology. It applied more widely to social and economic life. A few years back I wrote a book called Real England, which was also about conviviality, as it turned out. In particular, it was about how human-scale, vernacular ways of life in my home country were disappearing, victims of the march of the machine. Small shops were crushed by supermarkets, family farms pushed out of business by the global agricultural market, ancient orchards rooted up for housing developments, pubs shut down by developers and state interference. What the book turned out to be about, again, was autonomy and control: about the need for people to be in control of their tools and places rather than to remain cogs in the machine.

Critics of that book called it nostalgic and conservative, as they do with all books like it. They confused a desire for human-scale autonomy, and for the independent character, quirkiness, mess, and creativity that usually results from it, with a desire to retreat to some imagined “golden age.” It’s a familiar criticism, and a lazy and boring one. Nowadays, when I’m faced with digs like this, I like to quote E. F. Schumacher, who replied to the accusation that he was a “crank” by saying, “A crank is a very elegant device. It’s small, it’s strong, it’s lightweight, energy efficient, and it makes revolutions.” [Continue reading…]

Hacking the president’s DNA

Andrew Hessel, Marc Goodman and Steven Kotler write: This is how the future arrived. It began innocuously, in the early 2000s, when businesses started to realize that highly skilled jobs formerly performed in-house, by a single employee, could more efficiently be crowd-sourced to a larger group of people via the Internet. Initially, we crowd-sourced the design of T‑shirts (Threadless.com) and the writing of encyclopedias (Wikipedia.com), but before long the trend started making inroads into the harder sciences. Pretty soon, the hunt for extraterrestrial life, the development of self-driving cars, and the folding of enzymes into novel proteins were being done this way. With the fundamental tools of genetic manipulation—tools that had cost millions of dollars not 10 years earlier — dropping precipitously in price, the crowd-sourced design of biological agents was just the next logical step.

In 2008, casual DNA-design competitions with small prizes arose; then in 2011, with the launch of GE’s $100 million breast-cancer challenge, the field moved on to serious contests. By early 2015, as personalized gene therapies for end-stage cancer became medicine’s cutting edge, virus-design Web sites began appearing, where people could upload information about their disease and virologists could post designs for a customized cure. Medically speaking, it all made perfect sense: Nature had done eons of excellent design work on viruses. With some retooling, they were ideal vehicles for gene delivery.

Soon enough, these sites were flooded with requests that went far beyond cancer. Diagnostic agents, vaccines, antimicrobials, even designer psychoactive drugs — all appeared on the menu. What people did with these bio-designs was anybody’s guess. No international body had yet been created to watch over them.

So, in November of 2016, when a first-time visitor with the handle Cap’n Capsid posted a challenge on the viral-design site 99Virions, no alarms sounded; his was just one of the 100 or so design requests submitted that day. Cap’n Capsid might have been some consultant to the pharmaceutical industry, and his challenge just another attempt to understand the radically shifting R&D landscape — really, he could have been anyone — but the problem was interesting nonetheless. Plus, Capsid was offering $500 for the winning design, not a bad sum for a few hours’ work.

Later, 99Virions’ log files would show that Cap’n Capsid’s IP address originated in Panama, although this was likely a fake. The design specification itself raised no red flags. Written in SBOL, an open-source language popular with the synthetic-biology crowd, it seemed like a standard vaccine request. So people just got to work, as did the automated computer programs that had been written to “auto-evolve” new designs. These algorithms were getting quite good, now winning nearly a third of the challenges.

Within 12 hours, 243 designs were submitted, most by these computerized expert systems. But this time the winner, GeneGenie27, was actually human — a 20-year-old Columbia University undergrad with a knack for virology. His design was quickly forwarded to a thriving Shanghai-based online bio-marketplace. Less than a minute later, an Icelandic synthesis start‑up won the contract to turn the 5,984-base-pair blueprint into actual genetic material. Three days after that, a package of 10‑milligram, fast-dissolving microtablets was dropped in a FedEx envelope and handed to a courier.

Two days later, Samantha, a sophomore majoring in government at Harvard University, received the package. Thinking it contained a new synthetic psychedelic she had ordered online, she slipped a tablet into her left nostril that evening, then walked over to her closet. By the time Samantha finished dressing, the tab had started to dissolve, and a few strands of foreign genetic material had entered the cells of her nasal mucosa.

Some party drug — all she got, it seemed, was the flu. Later that night, Samantha had a slight fever and was shedding billions of virus particles. These particles would spread around campus in an exponentially growing chain reaction that was—other than the mild fever and some sneezing — absolutely harmless. This would change when the virus crossed paths with cells containing a very specific DNA sequence, a sequence that would act as a molecular key to unlock secondary functions that were not so benign. This secondary sequence would trigger a fast-acting neuro-destructive disease that produced memory loss and, eventually, death. The only person in the world with this DNA sequence was the president of the United States, who was scheduled to speak at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government later that week. Sure, thousands of people on campus would be sniffling, but the Secret Service probably wouldn’t think anything was amiss.

It was December, after all—cold-and-flu season.

The scenario we’ve just sketched may sound like nothing but science fiction — and, indeed, it does contain a few futuristic leaps. Many members of the scientific community would say our time line is too fast. But consider that since the beginning of this century, rapidly accelerating technology has shown a distinct tendency to turn the impossible into the everyday in no time at all. Last year, IBM’s Watson, an artificial intelligence, understood natural language well enough to whip the human champion Ken Jennings on Jeopardy. As we write this, soldiers with bionic limbs are returning to active duty, and autonomous cars are driving down our streets. Yet most of these advances are small in comparison with the great leap forward currently under way in the biosciences — a leap with consequences we’ve only begun to imagine.

More to the point, consider that the DNA of world leaders is already a subject of intrigue. According to Ronald Kessler, the author of the 2009 book In the President’s Secret Service, Navy stewards gather bedsheets, drinking glasses, and other objects the president has touched — they are later sanitized or destroyed — in an effort to keep would‑be malefactors from obtaining his genetic material. (The Secret Service would neither confirm nor deny this practice, nor would it comment on any other aspect of this article.) And according to a 2010 release of secret cables by WikiLeaks, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton directed our embassies to surreptitiously collect DNA samples from foreign heads of state and senior United Nations officials. Clearly, the U.S. sees strategic advantage in knowing the specific biology of world leaders; it would be surprising if other nations didn’t feel the same.

While no use of an advanced, genetically targeted bio-weapon has been reported, the authors of this piece — including an expert in genetics and microbiology (Andrew Hessel) and one in global security and law enforcement (Marc Goodman) — are convinced we are drawing close to this possibility. Most of the enabling technologies are in place, already serving the needs of academic R&D groups and commercial biotech organizations. And these technologies are becoming exponentially more powerful, particularly those that allow for the easy manipulation of DNA. [Continue reading…]

Higgs boson: A cause for celebration. But will it be our last great discovery?

When 30 years ago the Large Hadron Collider was first proposed, its construction was far from certain. Robin McKie writes: The US was then planning the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC), an underground tunnel – 54 miles in circumference – round which protons would be hurled at energies three times those generated by those in the LHC. Why construct an inferior device, critics asked?

But the SSC proved to be a debacle. Individual congressmen initially backed it because they hoped it would be built in their state. But after Texas was selected, those outside the state lost interest. Costs soared and the SSC, now friendless, was cancelled. So the US put its money into the international space station, a project of no scientific value but which upset no vested interests.

After its rival disappeared, the case for the LHC looked stronger. Yet it still took a decade of negotiations to get Cern’s member nations to agree to build it. Eventually a deal was signed – only for Britain, following its 1993 economic crisis, and Germany, reeling under the cost of reunification, to renege. In both cases, last-minute deals saved the project, although Llewellyn Smith says it had balanced, several times, on the edge of extinction. “It was touch and go on a number of occasions. It could so easily not have happened.”

And that point has clear implications for the LHC. If its giant detectors produce evidence of Higgs bosons and little else in its lifetime, particle physicists will struggle to persuade the world they need a bigger machine to probe even further into the structure of matter, a point stressed by the Nobel prize-winning physicist Steven Weinberg.

“My nightmare is that the LHC’s only important discovery will be the Higgs,” says Weinberg. “Its discovery was important. It confirms existing theory but it does not give us any new ideas. We need to find new things that cry out for further investigation if we are to get money for a next generation collider.”

Candidate discoveries would include particles that could explain the presence of dark matter in the universe. Astronomers know that the quarks, electrons and other forms of normal matter found on Earth can only explain about a sixth of the mass of the universe. There is something else out there. Scientists call it dark matter but cannot agree about its nature. A particle, as yet undetected, that permeates the cosmos, might be responsible.

As Weinberg says: “What could be more exciting than finding a particle that makes up most of the universe’s mass?” Certainly, finding hints of dark matter would help scientists get the billions they will need for a next generation collider. But if they find no exotic fare like this, they will flounder.

This point is backed by [Sir Christopher] Llewellyn Smith [Cern’s director general in the 1990s]. “The only real case for a next generation device would be the discovery of a phenomenon that the LHC could only just detect but could not study properly. We will have to wait and see if something like that happens. Certainly, it will give scientists plenty to do at the LHC for the next few years.”

As to the nature of that next generation device, by far the most likely candidate would be a linear – as opposed to a circular – accelerator which would fire electrons in straight lines for miles before smashing them together. A world consortium of experts, including Lyn Evans, has already been set up to create plans. But until the LHC produces results, its design will remain uncertain. “It is quite conceivable that we have reached the end of the line,” adds Llewellyn Smith. “Certainly, unless someone comes up with an unexpected breakthrough, it is hard not to conclude we have come about as far as we can with accelerator technology.” After 50 years of whizzing sub-atomic particles along tunnels before battering them together, we appear to be approaching the limits of this technology.

And even if the technical hurdles can be overcome, the political issues may be insurmountable. Battles over local interests will inevitably strike again. Scientists will then have to use other methods to study the fabric of the cosmos: powerful, space-based telescopes that could peer back into the early universe. On their own, these are unlikely to produce major breakthroughs. As a result, when LHC has completed its work next decade, we may face a long pause in our progress in unravelling the universe’s structure.

Why try to understand the nature of the universe?

Rhett Allain, an Associate Professor of Physics at Southeastern Louisiana University, talks about how to discuss the Higgs boson announcement in the classroom — especially with non-science majors.

Given that those of us who don’t understand particle physics have not spent years wondering whether a missing piece to the Standard Model would ever be discovered, it’s discovery will lead many to question the value of finding this elusive particle.

This could be the question the students start with. It is a great opportunity to talk about the nature of science. In short, the answer is that the Higgs boson isn’t used for anything.

Chad Orzel (@orzelc) likes to say “Science is the most fundamental human activity.” I like to change this around and say “We do science, because we are human.” This is really part of my favorite quote from Robert Heinlein:

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly.”

Looking for the pieces of Standard Model is a human activity – just like painting the Mona Lisa. Why is just about everyone interested in black holes? Is there a practical use for black hole technology? Ok – maybe there could be, … [but] I doubt it is in the near future. We (humans) are interested in black holes because we are humans and that’s what we do.

Will there be “spin off” technologies from these high energy particle accelerators? Of course – but that’s not the goal. Will there be technologies based on the Higgs boson? Possibly, but that’s not the reason (and it will be a long way away).

To legitimize science by saying we do science because we are human, doesn’t to my mind go to the heart of the issue of value.

One can say — as many have — that we fight wars because we are human. But this doesn’t give value to war — it merely suggests that war might be unavoidable. (Whether it is unavoidable is a debate for another occasion.)

Instead of addressing the question about the value of science by just talking about science, it might be better to talk about the nature of value.

From the materialistic vantage point of American culture, the value of science is invariably measured through its utility. Will it provide us with faster computers, more fuel-efficient cars, new medicines or new materials? Will it make us wealthier?

The assumption about value is that the value of A is the fact that it can produce B.

This notion of productive value is insidious and it blinds us to something we all instinctively know but easily forget: the things of greatest value have intrinsic value — they need no justification.

We don’t dance to go somewhere. A song doesn’t rush to its conclusion. Beauty is not enhanced by ownership. Curiosity should not be extinguished by knowledge.

To want to understand the nature of the universe is to possess a desire that needs no justification.