Category Archives: Attention to the Unseen

In brain surgery, experience reveals the importance of luck

Henry Marsh writes: I often have to cut into the brain and it is something I hate doing. With a pair of short-wave diathermy forceps I coagulate a few millimetres of the brain’s surface, turning the living, glittering pia arachnoid – the transparent membrane that covers the brain – along with its minute and elegant blood vessels, into an ugly scab. With a pair of microscopic scissors I then cut the blood vessels and dig downwards with a fine sucker. I look down the operating microscope, feeling my way through the soft white substance of the brain, trying to find the tumour. The idea that I am cutting and pushing through thought itself, that memories, dreams and reflections should have the consistency of soft white jelly, is simply too strange to understand and all I can see in front of me is matter. Nevertheless, I know that if I stray into the wrong area, into what neurosurgeons call eloquent brain, I will be faced with a damaged and disabled patient afterwards. The brain does not come with helpful labels saying ‘Cut here’ or ‘Don’t cut there’. Eloquent brain looks no different from any other area of the brain, so when I go round to the Recovery Ward after the operation to see what I have achieved, I am always anxious.

There are various ways in which the risk of doing damage can be reduced. There is a form of GPS for brain surgery called Computer Navigation where, instead of satellites orbiting the Earth, there are infrared cameras around the patient’s head which show the surgeon on a computer screen where his instruments are on the patient’s brain scan. You can operate with the patient awake The idea that . . . memories, dreams and reflections should have the consistency of soft white jelly, is simply too strange to understand under local anaesthetic: the eloquent areas of the brain can then be identified by stimulating the brain with an electrode and by giving the patient simple tasks to perform so that one can see if one is causing any damage as the operation proceeds. And then there is skill and experience and knowing when to stop. Quite often one must decide that it is better not to start in the first place and declare the tumour inoperable. Despite these methods, however, much still depends on luck, both good and bad. As I become more and more experienced, it seems that luck becomes ever more important.

I had a patient who had a tumour of the pineal gland. The dualist philosopher Descartes, who argued that mind and brain are entirely separate entities, placed the human soul in the pineal gland. It was here, he said, that the material brain in some magical and mysterious way communicated with the mind and with the immaterial soul. I wonder what he would have said if he could have seen my patients looking at their own brains on a video monitor, as some of them do when I operate under local anaesthetic.

Pineal tumours are very rare. They can be benign and they can be malignant. The benign ones do not necessarily need treatment. The malignant ones are treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy but can prove fatal nevertheless. In the past they were considered to be inoperable but with modern microscopic neurosurgery this is no longer the case: it is usually now considered necessary to operate at least to obtain a biopsy – to remove a small part of the tumour for a precise diagnosis of the type so that you can then decide how best to treat it. The biopsy result will tell you whether to remove all of the tumour or whether to leave most of it in place, and whether the patient needs radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Since the pineal is buried deep in the middle of the brain the operation is, as surgeons say, a technical challenge; neurosurgeons look with awe and excitement at brain scans showing pineal tumours, like mountaineers looking up at a great peak that they hope to climb. To make matters worse, this particular patient – a very fit and athletic man in his thirties who had developed severe headaches as the tumour obstructed the normal circulation of cerebro-spinal fluid around his brain – had found it very hard to accept that he had a life-threatening illness and that his life was now out of his control. I had had many anxious conversations and phone calls with him over the days before the operation. I explained that the risks of the surgery, which included death or a major stroke, were ultimately less than the risks of not operating. He laboriously typed everything I said into his smartphone, as if taking down the long words – obstructive hydrocephalus, endoscopic ventriculostomy, pineocytoma, pineoblastoma – would somehow put him back in charge and save him. Anxiety is contagious – it is one of the reasons surgeons must distance themselves from their patients – and his anxiety, combined with my feeling of profound failure about an operation I had carried out a week earlier meant that I faced the prospect of operating upon him with dread. I had seen him the night before the operation. When I see my patients the night before surgery I try not to dwell on the risks of the operation ahead, which I will already have discussed in detail at an earlier meeting. His wife was sitting beside him, looking quite sick with fear. [Continue reading…]

The optimism of accepting the inevitability of death

TED talks that should have been censored? Not if you want to know how to tie your shoes

“With all the fuss over TED’s self-censorship, we searched through hours of footage to find 10 talks the organizers really should have excised” writes Foreign Policy associate editor Joshua Keating.

Why? Just so that Foreign Policy readers could waste their time watching TED talks that in Keating’s view aren’t worth watching?

Curious to find out whether I happened to have already made the mistake of watching one of these scrappable talks I browsed the list. I had indeed watched the second one: Terry Moore’s presentation on how to tie your shoes.

Maybe Keating only wears loafers or maybe he happened to learn the strong knot when he first learned to tie laces, but for anyone like Moore or me who has gone fifty or more years with shoes laces that with irritating frequency have habit of coming loose, this lesson in shoe lace tying is of immense value. It also demonstrates how easy it is to move through life thinking you know something only to discover you were ignorant.

Video: Reuben Margolin — Sculpting waves in wood and time

In meditative mindfulness, Rep. Tim Ryan sees a cure for many American ills

The Washington Post reports: Rep. Tim Ryan (D) is a five-term incumbent from the heartland. His Ohio district includes Youngstown and Warren and part of Akron and smaller places. He’s 38, Catholic, single. He was a star quarterback in high school. He lives a few houses down from his childhood home in Niles. He’s won three of his five elections with about 75 percent of the vote.

So when he starts talking about his life-changing moment after the 2008 race, you’re not expecting him to lean forward at the lunch table and tell you, with great sincerity, that this little story of American politics is about (a) a raisin and (b) nothing else.

“You hold this one raisin right up to your mouth, but you don’t put it in, and after a moment your mouth starts to water,” he says, describing an exercise during a five-day retreat into the meditative technique of mindfulness, developed from centuries of Buddhist practice. “The teaching point is that your body responds to things outside of it, that there’s a mind-body connection. It links to how we take on situations and how this results in a great deal of stress.”

For Ryan, the raisin was the beginning of a transformation. The retreat, conducted by Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, led Ryan on a search into how the practice of mindfulness — sitting in silence, losing oneself in the present moment — could be a tonic for what ails the body politic.

In “A Mindful Nation,” published last week, Ryan details his travels across the country, to schools and companies and research facilities, documenting how mindfulness is relieving stress, improving performance and showing potential to reduce health-care costs. It is a prescription, he says, that can help the nation better deal with the constant barrage of information that the Internet age delivers.

“I think when you realize that U.S. Marines are using this that it’s already in the mainstream of our culture,” he says. “It’s a real technique that has real usefulness that has been scientifically documented. . . . Why wouldn’t we have this as part of our health-care program to prevent high levels of stress that cause heart disease and ulcers and Type 2 diabetes and everything else?”

Video: Learning from failure

Music: Michal Levy — One

Bashnia Tatlina Tower Bawher:

IBM smashes Moore’s Law, cuts bit size to 12 atoms

Computerworld reports: IBM announced Thursday that after five years of work, its researchers have been able to reduce from about one million to 12 the number of atoms required to create a bit of data.

The breakthrough may someday allow data storage hardware manufacturers to produce products with capacities that are orders of magnitude greater than today’s hard disk and flash drives.

“Looking at this conservatively … instead of 1TB on a device you’d have 100TB to 150TB. Instead of being able to store all your songs on a drive, you’d be able to have all your videos on the device,” said Andreas Heinrich, IBM Research Staff Member and lead investigator on this project.

Today, storage devices use ferromagnetic materials where the spin of atoms are aligned or in the same direction.

The IBM researchers used an unconventional form of magnetism called antiferromagnetism, where atoms spin in opposite directions, allowing scientists to create an experimental atomic-scale magnet memory that is at least 100 times denser than today’s hard disk drives and solid-state memory chips.

The Earth is one among a trillion planets in the Milky Way

PopSci reports: Each star in the Milky Way shines its light upon at least one companion planet, according to a new analysis that suddenly renders exoplanets commonplace, the rule rather than the exception. This means there are billions of worlds just in our corner of the cosmos. This is a major shift from just a few years ago, when many scientists thought planets were tricky to make, and therefore special things. Now we know they’re more common than stars themselves.

“Planets are like bunnies; you don’t just get one, you get a bunch,” said Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the SETI Institute who was not involved in this research. “So really, the number of planets in the Milky Way is probably like five or 10 times the number of stars. That’s something like a trillion planets.”

Of course there’s no way to know, at least not yet, how many of these worlds could be hospitable to forms of life as we know it. But the odds alone are tantalizing, Shostak said.

“It’s not unreasonable at this point to say there are literally billions of habitable worlds in our galaxy, probably as a lower limit,” he said. “Maybe they’re all sterile as an autoclave, but it doesn’t seem very likely, does it? That would make us very odd.”

Attention to the unseen

Regular readers of War in Context might be perplexed about some of the items that have been popping up here lately — particularly those that appear under my generic and cryptic byline: Attention to the Unseen.

Here’s another one — but this isn’t just another seemingly “off-topic” post. It also illustrates one of the reasons I am picking out such items.

In Intelligent Life, Ian Leslie writes: One day in 1945, a man named Percy Spencer was touring one of the laboratories he managed at Raytheon in Waltham, Massachusetts, a supplier of radar technology to the Allied forces. He was standing by a magnetron, a vacuum tube which generates microwaves, to boost the sensitivity of radar, when he felt a strange sensation. Checking his pocket, he found his candy bar had melted. Surprised and intrigued, he sent for a bag of popcorn, and held it up to the magnetron. The popcorn popped. Within a year, Raytheon made a patent application for a microwave oven.

The history of scientific discovery is peppered with breakthroughs that came about by accident. The most momentous was Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928, prompted when he noticed how a mould that floated into his Petri dish killed off the surrounding bacteria. Spencer and Fleming didn’t just get lucky. Spencer had the nous and the knowledge to turn his observation into innovation; only an expert on bacteria would have been ready to see the significance of Fleming’s stray spore. As Louis Pasteur wrote, “In the field of observation, chance favours only the prepared mind.”

The word that best describes this subtle blend of chance and agency is “serendipity”. It was coined by Horace Walpole, man of letters and aristocratic dilettante. Writing to a friend in 1754, Walpole explained an unexpected discovery he had just made by reference to a Persian fairy tale, “The Three Princes of Serendip”. The princes, he told his correspondent, were “always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of…now do you understand Serendipity?” These days, we tend to associate serendipity with luck, and we neglect the sagacity. But some conditions are more conducive to accidental discovery than others.

Today’s world wide web has developed to organise, and make sense of, the exponential increase in information made available to everyone by the digital revolution, and it is amazingly good at doing so. If you are searching for something, you can find it online, and quickly. But a side-effect of this awesome efficiency may be a shrinking, rather than an expansion, of our horizons, because we are less likely to come across things we are not in quest of.

To some extent, War in Context reflects this web-wide narrowing of attention in its focus on Middle East politics. But now, in my own attempt to buck this wider trend and also reflect the fact that my own interests are not limited to the enduring political reverberations of 9/11, I am using “attention to the unseen” as an amorphous theme where I will call attention to gleanings from the web covering topics as diverse as endangered cultures and neuroscience, or the social organization of bees and avant-garde accordion music.

The paralyzing effect of choice

Professor Renata Salecl explores the paralyzing anxiety and dissatisfaction surrounding limitless choice. Her unedited, unanimated talk can be viewed here.

Pinker’s dirty war on prehistoric peace

Christopher Ryan challenges Steven Pinker’s dubious claim that we live in the most peaceful of times. Pinker bases his argument on a comparison of male deaths due to war using what he treats as modern tribal correlates of our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

The seven cultures listed on Pinker’s chart are the Jivaro, two branches of Yanomami, the Mae Enga, Dugum Dani, Murngin, Huli, and Gebusi.

Are these societies actually representative of our hunter-gatherer ancestors?

No.

Are they even hunter-gatherers at all?

Hell no.

Only the Murngin even approach being an immediate-return hunter-gatherer society like our prehistoric ancestors, and they had been living with missionaries, guns, and aluminum powerboats for decades by 1975, when the data Pinker cites were collected.

None of the other societies cited by Pinker are even arguably immediate-return hunter-gatherers like our ancestors. They cultivate yams, bananas, or sugarcane in village gardens while raising domesticated pigs, llamas, or chickens. This is crucial, because societies are far more likely to wage war when they have things worth fighting over (pigs, gardens, settled villages), but tend to be far less conflictive when living as nomadic hunter-gatherers, with little to plunder or defend. Any first-year anthropology student knows this. Presumably, so does Pinker.

Beyond the fact that these societies are not remotely representative of our nomadic hunter-gatherer ancestors, there are more problems with the data Pinker cites. Among the Yanomami, true levels of warfare are subject to passionate debate among anthropologists. The Murngin are not typical even of Australian native cultures, representing a bloody exception to the typical pattern of little to no intergroup conflict. Nor does Pinker get the Gebusi right. Bruce Knauft, the anthropologist whose research is cited on this chart, reports that warfare is “rare” among the Gebusi, writing, “Disputes over territory or resources are extremely infrequent and tend to be easily resolved.”

To make matters even worse, Pinker juxtaposes these bogus “hunter-gatherer” mortality rates with a tiny bar showing the relatively few “war-related deaths of males in twentieth-century United States and Europe.” This is a false comparison because the twentieth century gave birth to “total war” between nations, in which civilians were targeted (Dresden, Hiroshima, Nagasaki… ), so counting only male military deaths requires ignoring all the millions of civilians victimized by war.

Deb Roy: The birth of a word

How many friends does one person need?

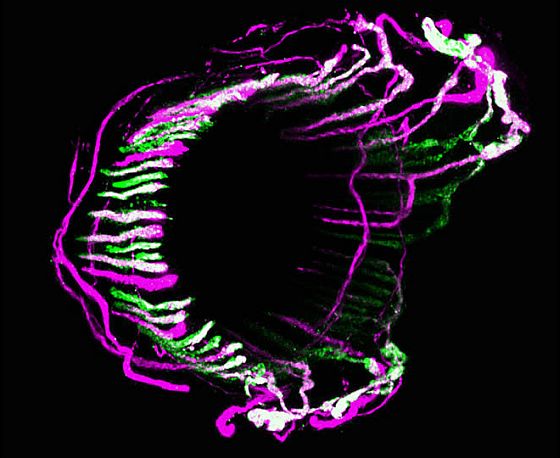

The intricate circuitry revealed in new mapping of the neurons of touch

Guard hair palisade neural endings cell in a mouse.

Wired reports on a study [PDF] mapping tactile neurons, co-authored by Jeff Woodbury of the University of Wyoming: To untangle the wiring, Woodbury and other researchers led by neuroscientist David Ginty of Johns Hopkins University began with mouse nervous systems. They focused on a class of nerve endings called low-threshold mechanosensory receptors, or LTMRs, which are sensitive to the slightest of sensations: a mosquito’s footsteps, a hint of breeze.

The researchers identified genes active only in types of LTMRs at the base of ultra-sensitive hairs. Then, in mouse embryos, they tagged those genes with fluorescent proteins. The result: an engineered mouse strain illuminating the full, precise paths of LTMR cells.

Under a microscope, the researchers tracked three different types of LTMRs in never-before-seen detail, plus a fourth well-studied type. “This enabled us, for the first time, to nail down and tie specialized nerve endings to functions,” Woodbury said.

By following LTMRs all the way into ganglia and out the other side into the spinal cord, the researchers discovered a layering pattern that resembles the organization of neurons in the cerebral cortex — the outermost layer of the brain with major roles in consciousness, memory, attention and other roles.

With four of the two dozen different nerve ending types now traceable, the researchers are now working to tag the rest. Someday, perhaps, their technique could lead to complete neural maps of touch.