Luke Massey writes: Slavoj Žižek is brimming with thought. Each idea sprays out of the controversial Slovenian philosopher and cultural theorist in a jet of words. He is like a water balloon, perforated in so many areas that its content gushes out in all directions.

The result is that, as an interviewer, trying to give direction to the tide is a joyfully hopeless enterprise. Perhaps more significantly, the same seems to be true for Žižek himself.

We meet in a room with one glass wall – an apt setting for a discussion of freedom, ideology, surveillance and ‘80s dystopias on film. Picturehouse HQ is playing host to our discussion, on the launch of Žižek’s new film The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology.

Before I even ask my first question, Slavoj is off: he tells me that I’m better than some interviewers he’s met. The fact that I’ve barely spoken yet doesn’t seem a barrier to that. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Culture

Audio: Proto-Indo-European reconstructed

Here’s a story in English:

A sheep that had no wool saw horses, one of them pulling a heavy wagon, one carrying a big load, and one carrying a man quickly. The sheep said to the horses: “My heart pains me, seeing a man driving horses.” The horses said: “Listen, sheep, our hearts pain us when we see this: a man, the master, makes the wool of the sheep into a warm garment for himself. And the sheep has no wool.” Having heard this, the sheep fled into the plain.

And here is “a very educated approximation” of how that story might have sounded if spoken in Proto-Indo-European about 6,500 years ago:

(Read more at Archeology.)

Americans aren’t exceptional — they are weird

Ethan Watters writes: In the summer of 1995, a young graduate student in anthropology at UCLA named Joe Henrich traveled to Peru to carry out some fieldwork among the Machiguenga, an indigenous people who live north of Machu Picchu in the Amazon basin. The Machiguenga had traditionally been horticulturalists who lived in single-family, thatch-roofed houses in small hamlets composed of clusters of extended families. For sustenance, they relied on local game and produce from small-scale farming. They shared with their kin but rarely traded with outside groups.

While the setting was fairly typical for an anthropologist, Henrich’s research was not. Rather than practice traditional ethnography, he decided to run a behavioral experiment that had been developed by economists. Henrich used a “game”—along the lines of the famous prisoner’s dilemma—to see whether isolated cultures shared with the West the same basic instinct for fairness. In doing so, Henrich expected to confirm one of the foundational assumptions underlying such experiments, and indeed underpinning the entire fields of economics and psychology: that humans all share the same cognitive machinery—the same evolved rational and psychological hardwiring.

The test that Henrich introduced to the Machiguenga was called the ultimatum game. The rules are simple: in each game there are two players who remain anonymous to each other. The first player is given an amount of money, say $100, and told that he has to offer some of the cash, in an amount of his choosing, to the other subject. The second player can accept or refuse the split. But there’s a hitch: players know that if the recipient refuses the offer, both leave empty-handed. North Americans, who are the most common subjects for such experiments, usually offer a 50-50 split when on the giving end. When on the receiving end, they show an eagerness to punish the other player for uneven splits at their own expense. In short, Americans show the tendency to be equitable with strangers—and to punish those who are not.

Among the Machiguenga, word quickly spread of the young, square-jawed visitor from America giving away money. The stakes Henrich used in the game with the Machiguenga were not insubstantial—roughly equivalent to the few days’ wages they sometimes earned from episodic work with logging or oil companies. So Henrich had no problem finding volunteers. What he had great difficulty with, however, was explaining the rules, as the game struck the Machiguenga as deeply odd.

When he began to run the game it became immediately clear that Machiguengan behavior was dramatically different from that of the average North American. To begin with, the offers from the first player were much lower. In addition, when on the receiving end of the game, the Machiguenga rarely refused even the lowest possible amount. “It just seemed ridiculous to the Machiguenga that you would reject an offer of free money,” says Henrich. “They just didn’t understand why anyone would sacrifice money to punish someone who had the good luck of getting to play the other role in the game.”

The potential implications of the unexpected results were quickly apparent to Henrich. He knew that a vast amount of scholarly literature in the social sciences—particularly in economics and psychology—relied on the ultimatum game and similar experiments. At the heart of most of that research was the implicit assumption that the results revealed evolved psychological traits common to all humans, never mind that the test subjects were nearly always from the industrialized West. Henrich realized that if the Machiguenga results stood up, and if similar differences could be measured across other populations, this assumption of universality would have to be challenged.

Henrich had thought he would be adding a small branch to an established tree of knowledge. It turned out he was sawing at the very trunk. He began to wonder: What other certainties about “human nature” in social science research would need to be reconsidered when tested across diverse populations? [Continue reading…]

Long lives made humans human

Laura Helmuth writes: The fundamental structure of human populations has changed exactly twice in evolutionary history. The second time was in the past 150 years, when the average lifespan doubled in most parts of the world. The first time was in the Paleolithic, probably around 30,000 years ago. That’s when old people were basically invented.

Throughout hominid history, it was exceedingly rare for individuals to live more than 30 years. Paleoanthropologists can examine teeth to estimate how old a hominid was when it died, based on which teeth are erupted, how worn down they are, and the amount of a tissue called dentin. Anthropologist Rachel Caspari of Central Michigan University used teeth to identify the ratio of old to young people in Australopithecenes from 3 million to 1.5 million years ago, early Homo species from 2 million to 500,000 years ago, and Neanderthals from 130,000 years ago. Old people — old here means older than 30 (sorry) — were a vanishingly small part of the population. When she looked at modern humans from the Upper Paleolithic, about 30,000 years ago, though, she found the ratio reversed — there were twice as many adults who died after age 30 as those who died young.

The Upper Paleolithic is also when modern humans really started flourishing. That’s one of the times the population boomed and humans created complex art, used symbols, and colonized even inhospitable environments. (The modern humans she studied lived in Europe during some of the bitterest millennia of the last Ice Age.) Caspari says it wasn’t a biological change that allowed people to start living reliably to their 30s and beyond. (When she looked at other populations of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens that lived in the same place and time, the two different species had similar proportions of old people, suggesting the change was not genetic.) Instead, it was culture. Something about how people were living made it possible to survive into old age, maybe the way they found or stored food or built shelters, who knows. That’s all lost — pretty much all we have of them is teeth — but once humans found a way to keep old people around, everything changed.

Old people are repositories of information, Caspari says. They know about the natural world, how to handle rare disasters, how to perform complicated skills, who is related to whom, where the food and caves and enemies are. They maintain and build intricate social networks. A lot of skills that allowed humans to take over the world take a lot of time and training to master, and they wouldn’t have been perfected or passed along without old people. “They can be great teachers,” Caspari says, “and they allow for more complex societies.” Old people made humans human. [Continue reading…]

While life extension allowed culture to blossom, the proliferation of culture long preceded the emergence of civilization which brought with it the extension and entrenching of ownership, the control of language through script, and the institutionalization of inequality.

While culture allowed people to live longer, civilization extended the lives of some while shortening the lives of others.

Ancient climate change and human cultural development

Cardiff University: Rapid climate change during the Middle Stone Age, between 80,000 and 40,000 years ago, during the Middle Stone Age, sparked surges in cultural innovation in early modern human populations, according to new research.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications [21 May], was conducted by a team of scientists from Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, the Natural History Museum in London and the University of Barcelona.

The scientists studied a marine sediment core off the coast of South Africa and reconstructed terrestrial climate variability over the last 100,000 years.

Dr Martin Ziegler, Cardiff University School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, said: “We found that South Africa experienced rapid climate transitions toward wetter conditions at times when the Northern Hemisphere experienced extremely cold conditions.”

These large Northern Hemisphere cooling events have previously been linked to a change in the Atlantic Ocean circulation that led to a reduced transport of warm water to the high latitudes in the North. In response to this Northern Hemisphere cooling, large parts of the sub-Saharan Africa experienced very dry conditions.

“Our new data however, contrasts with sub-Saharan Africa and demonstrates that the South African climate responded in the opposite direction, with increasing rainfall, that can be associated with a globally occurring southward shift of the tropical monsoon belt.”

Professor Ian Hall, Cardiff University School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, said: “When the timing of these rapidly occurring wet pulses was compared with the archaeological datasets, we found remarkable coincidences.

“The occurrence of several major Middle Stone Age industries fell tightly together with the onset of periods with increased rainfall”

“Similarly, the disappearance of the industries appears to coincide with the transition to drier climatic conditions.”

Professor Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum commented “The correspondence between climatic ameliorations and cultural innovations supports the view that population growth fuelled cultural changes, through increased human interactions”.

The South African archaeological record is so important because it shows some of the oldest evidence for modern behavior in early humans. This includes the use of symbols, which has been linked to the development of complex language, and personal adornments made of seashells.

“The quality of the southern African data allowed us to make these correlations between climate and behavioural change, but it will require comparable data from other areas before we can say whether this region was uniquely important in the development of modern human culture” added Professor Stringer.

The new study presents the most convincing evidence so far that abrupt climate change was instrumental in this development.

The research was supported by the UK Natural Environment Research Council and is part of the international Gateways training network, funded by the 7th Framework Programme of the European Union.

Video: On the myth of progress

Ubuntu — the essence of being human

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: A person with Ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good, for he or she has a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole and is diminished when others are humiliated or diminished, when others are tortured or oppressed.

One of the sayings in our country is Ubuntu – the essence of being human. Ubuntu speaks particularly about the fact that you can’t exist as a human being in isolation. It speaks about our interconnectedness. You can’t be human all by yourself, and when you have this quality – Ubuntu – you are known for your generosity.

We think of ourselves far too frequently as just individuals, separated from one another, whereas you are connected and what you do affects the whole world. When you do well, it spreads out; it is for the whole of humanity.

Beer, mushrooms, and civilization

Lascaux Paleolithic cave paintings, estimated to be 17,300 years old.

The psychiatrist, Jeffrey P. Kahn, suggests that the flowering of civilization may have been fueled by the creation of beer, a practice that could have evolved as early as 10,000 years ago providing occasional relief from the constraints of social conformity.

Once the effects of these early brews were discovered, the value of beer (as well as wine and other fermented potions) must have become immediately apparent. With the help of the new psychopharmacological brew, humans could quell the angst of defying those herd instincts. Conversations around the campfire, no doubt, took on a new dimension: the painfully shy, their angst suddenly quelled, could now speak their minds.

But the alcohol would have had more far-ranging effects, too, reducing the strong herd instincts to maintain a rigid social structure. In time, humans became more expansive in their thinking, as well as more collaborative and creative. A night of modest tippling may have ushered in these feelings of freedom — though, the morning after, instincts to conform and submit would have kicked back in to restore the social order.

I don’t find this a particularly persuasive line of speculation. It seems much more likely that beer served a role in sustaining the social order rather than freeing the imagination.

Records from 5,000 years ago show that enslaved farm laborers were being provided by their masters with a staple diet of barley gruel and weak beer — provisions barely sufficient to prevent starvation. The beer — not unlike the most popular watery brews of today — seems like it might have served more as a tool of pacification than a liberator of creativity. Indeed, if the advent of civilization opened up new avenues for exploring the human spirit for a newly emerging creative class, it simultaneously created the need for a new class of workers who would obediently follow directions without plotting insurrections.

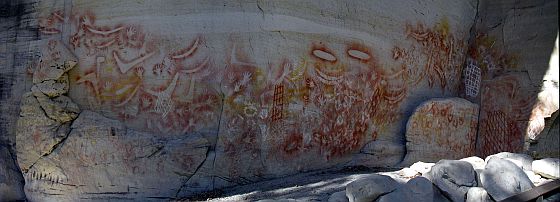

Knowledge about botanical tools for expanding consciousness most likely long preceded civilization. On several continents evidence of the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms can be found in rock art and rock art itself appears to go back as far as 40,000 years. Whatever social, ritual, or religious function such art may have performed it appears to express the kind of creative exuberance suggesting that for these primeval artists the creative act was an end in itself. And whether that creativity was unleashed by hallucinogens is perhaps besides the point. Clearly, human beings required neither civilization nor beer in order to become creative.

Civilization is celebrated because among other things it led to the creation of writing, yet in terms of creativity the transition from rock art to writing was regressive. The former served in enabling a magical transmutation: the ephemeral, intangible stuff of imagination was turned into physical form. Writing, on the other hand, initially served as a tool for exploitation. It allowed claims of ownership and laws to be set in stone. Its function at the beginning of civilization was to shackle the imagination and codify authority.

If beer was essential for pacifying slaves, it may also have functioned in defining a boundary that legitimized alcohol while prohibiting hallucinogens. Just as the U.S. army demonstrated when experimenting with the use of LSD in chemical warfare, the potential such drugs have for undermining conventions of social order suggest they would commonly be perceived as a threat to civilization.

If beer was civilizing this might say less about the socially liberating effect of alcohol than it says about the need for social elites to limit the ambitions of those upon whose labor they depend. A central nervous system depressant could be employed as a way to release slaves from their leg irons by shackling their brains.

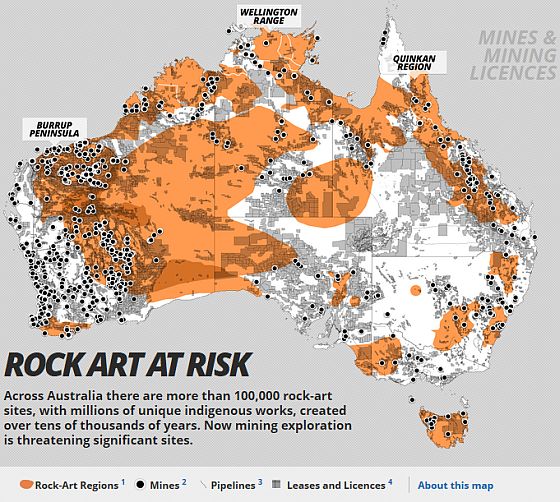

The devastating cost of Australia’s mining boom

Global Mail reports: Tucked away in the sandstone ridges of the rugged tropics near Australia’s north-eastern tip, the ochre “bullymen” with their big penises and staring eyes still cling to the rock.

These are secret paintings, made by Aboriginal men who were driven from their lowlands by colonials hungry for gold, and who were then harassed in the hills by the Native Mounted Police, both black troopers and their white officers.

The locals painted the police, or “bullymen”, onto the rock, in the belief that these works would conquer the enemy through sorcery, as Tommy George, a descendant of the “black trackers” now in his 80s (and the last surviving speaker of Agu Alaya, or Taipan Snake language) has explained to archaeologist Noelene Cole.

The Aboriginal fugitives believed that the paintings were a weapon that gave them power over the armed lawmen, George explained.

“It was so deeply embedded in culture that they could use the rock paintings to kill people – that’s how powerful the art was.

“The paintings were there to kill the police.

“It shows the power of that visual culture. They thought it was as strong as guns,” Cole said.

But now these poignant paintings, along with hundreds of other Aboriginal works in this remote Queensland gallery, which United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has recognised as one of the great rock-art precincts of the globe, are under a new threat from another power source: mining.

Prospectors have targeted the land beneath and around the art because it is rich in exploitable resources. These paintings are emblematic of the perils befalling rock art throughout Australia, where the resources sector has been booming for more than a decade, fuelled by China’s insatiable energy needs.

This is a recurring Australian story, as mining, industry and urbanisation surge across a landscape which harbours millions of images at more than 100,000 rock-art sites. State and territory heritage laws have proved weak in protecting the works, under governments keen to cash in on the mining bonanza. [Continue reading…]

Ode to a flower

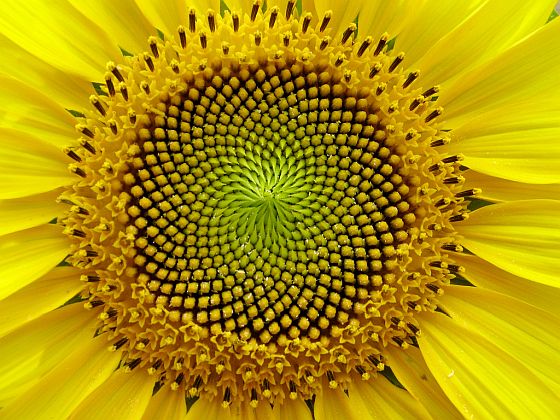

Richard Feynman’s friend should have known better than to bait the scientist — yet Feynman’s response proves the point: an understanding of the flower’s cellular structure, its evolution, and the evolutionary function of its beauty are all steps away from the experience of beholding a flower’s beauty.

When Feynman says he might not be “quite as refined aesthetically” as his friend, he’s marginalizing the value of perception, yet a flower is irreducibly an object of perception.

Drill into the structure of a sunflower petal and you may discover the molecular form of the pigments which are the physical substrate of color but you won’t find the essence of yellow since this is only manifest as light, flower, eye, and sentient awareness intersect. Yellow is an experience.

What serves neither art nor science is to treat either as offering a superior method for the appreciation of nature. An artist can profit from a class in cellular biology and scientists can expand their awareness by finding out what it means to open the doors of perception — to be able to see as if seeing the world for the first time.

Science opens doors of exquisite conceptual detail and leads into fascinating fields of exploration, but it doesn’t embrace the full range of the human experience — an experience in which we can be invigorated by losing our selves.

That a scientist and an artist would even be having the argument Feynman describes, speaks above all to a failed educational system.

Who can look carefully at the photograph below and explain why art, poetry, geometry, and biology are not taught in the very same classroom?

We fragment our world into domains of expertise as though no one should be allowed the privilege of exploring the totality.

Video: Half of humanity’s intellectual, social, and spiritual legacy is being allowed to slip away

Wade Davis: “If human beings are the agents of cultural destruction, we can also be and must be the facilitators of cultural survival.”

Christmas for atheists

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks writes: [Darwin] was puzzled by a phenomenon that seemed to contradict his most basic thesis, that natural selection should favor the ruthless. Altruists, who risk their lives for others, should therefore usually die before passing on their genes to the next generation. Yet all societies value altruism, and something similar can be found among social animals, from chimpanzees to dolphins to leafcutter ants.

Neuroscientists have shown how this works. We have mirror neurons that lead us to feel pain when we see others suffering. We are hard-wired for empathy. We are moral animals.

The precise implications of Darwin’s answer are still being debated by his disciples — Harvard’s E. O. Wilson in one corner, Oxford’s Richard Dawkins in the other. To put it at its simplest, we hand on our genes as individuals but we survive as members of groups, and groups can exist only when individuals act not solely for their own advantage but for the sake of the group as a whole. Our unique advantage is that we form larger and more complex groups than any other life-form.

A result is that we have two patterns of reaction in the brain, one focusing on potential danger to us as individuals, the other, located in the prefrontal cortex, taking a more considered view of the consequences of our actions for us and others. The first is immediate, instinctive and emotive. The second is reflective and rational. We are caught, in the psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s phrase, between thinking fast and slow.

The fast track helps us survive, but it can also lead us to acts that are impulsive and destructive. The slow track leads us to more considered behavior, but it is often overridden in the heat of the moment. We are sinners and saints, egotists and altruists, exactly as the prophets and philosophers have long maintained.

If this is so, we are in a position to understand why religion helped us survive in the past — and why we will need it in the future. It strengthens and speeds up the slow track. It reconfigures our neural pathways, turning altruism into instinct, through the rituals we perform, the texts we read and the prayers we pray. It remains the most powerful community builder the world has known. Religion binds individuals into groups through habits of altruism, creating relationships of trust strong enough to defeat destructive emotions. Far from refuting religion, the Neo-Darwinists have helped us understand why it matters.

No one has shown this more elegantly than the political scientist Robert D. Putnam. In the 1990s he became famous for the phrase “bowling alone”: more people were going bowling, but fewer were joining bowling teams. Individualism was slowly destroying our capacity to form groups. A decade later, in his book “American Grace,” he showed that there was one place where social capital could still be found: religious communities.

While extolling the virtue of the altruistic tendencies of church- or synagogue-goers, Sacks misses an opportunity to make his message more ecumenically inclusive and include mosque-goers. That’s a strange omission given that charity is one of the pillars of Islam. Moreover, he seems to conflate religion and values — a distinction that is clear in most people’s minds since the drift away from organized religion much more often results from a rejection of religious beliefs than religious values.

The problem that we atheists face — and probably one of the many reasons religion survives — is that our disbelief gives us less to celebrate. Of course we can celebrate life, but we can’t so easily contrive occasions where, obedient to the passage of time, we come together and reaffirm our shared values. Religion provides such pretexts for social unity, without discussion, consensus building or the messy process of negotiation that secular, values-based, collective bonding would entail.

The virtue of ritual and celebration is that they invite a form of selfless participation. They are not burdened by association with individual inventors and thus remain untouched by the competing force of reinvention by innovators — those who might insist for instance that it really makes more sense to celebrate Christmas on December 21, the Winter Solstice.

Maybe at some point, secular traditions of celebration will emerge if, in accordance with Jeremy Rifkin’s hope, we succeed in constructing an empathic civilization — but I suspect that if this happens it will be the result of an incremental adaptation of religion and not because Richard Dawkins and others succeeded in persuading the religious to abandon their faith.

Video: Richard Dawkins on religion

Al Jazeera describes this as an interview but it’s more of a debate — the New Statesman‘s Mehdi Hasan doesn’t give Dawkins an easy ride.

The world’s most prominent militant atheist suffers from the same disease that afflicts all other evangelists: a lack of curiosity about the very people they hope to change.

The mission of the new atheists seems akin to wanting to eradicate smallpox yet having little interest in studying the virus.

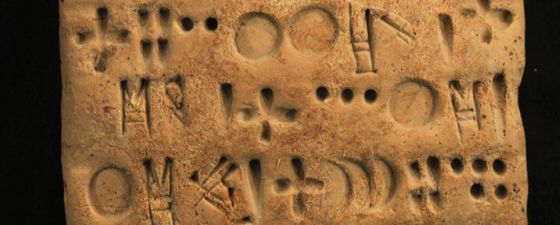

The written word — an ancient tool of oppression

The advent of writing is generally viewed in terms of its significance as a cultural advance — less attention is given to its political implications. Yet it looks like the most important function writing originally served was in the management of slavery and the regulation of society.

The BBC’s Sean Coughlan reports on efforts to understand proto-Elamite, the world’s oldest undeciphered writing system, which was used in an area that is now in south-western Iran over 5,000 years ago. The script was imprinted in clay tablets.

These were among the first attempts by our human ancestors to try to make a permanent record of their surroundings. What we’re doing now – my writing and your reading – is a direct continuation.

But there are glimpses of their lives to suggest that these were tough times. It wasn’t so much a land of milk and honey, but porridge and weak beer.

Even without knowing all the symbols, Dr [Jacob] Dahl [director of the Ancient World Research Cluster at Oxford University] says it’s possible to work out the context of many of the messages on these tablets.

The numbering system is also understood, making it possible to see that much of this information is about accounts of the ownership and yields from land and people. They are about property and status, not poetry.

This was a simple agricultural society, with a ruling household. Below them was a tier of powerful middle-ranking figures and further below were the majority of workers, who were treated like “cattle with names”.

Their rulers have titles or names which reflect this status – the equivalent of being called “Mr One Hundred”, he says – to show the number of people below him.

It’s possible to work out the rations given to these farm labourers.

Dr Dahl says they had a diet of barley, which might have been crushed into a form of porridge, and they drank weak beer.

The amount of food received by these farm workers hovered barely above the starvation level.

However the higher status people might have enjoyed yoghurt, cheese and honey. They also kept goats, sheep and cattle.

For the “upper echelons, life expectancy for some might have been as long as now”, he says. For the poor, he says it might have been as low as in today’s poorest countries.

If we think of writing as an observer’s record-keeping we might imagine some kind of proto-historian assuming the task of creating these first tablets, yet their content as described above makes it clear that these texts had a purely utilitarian function — they were records for the ruling class. Indeed, the creation of writing was likely one of the necessary conditions that facilitated the development and expansion of ownership.

Before the Neolithic Revolution and the first development of agriculture, as wandering hunter-gatherers, our ancestors had virtually no possessions. Without the ability to accrue personal power by being able to control material resources and stockpile food, social groupings — as can still be observed in the last remaining contemporary hunter-gatherer societies — were naturally egalitarian and cooperative.

For inequality to develop we had to stop moving around and start acquiring property and the maintenance of property required writing: a kind of spell-keeping through which an audacious idea — this is mine — could be invested in objects that lay outside the owner’s physical grasp. Writing constituted proof of ownership and the power of writing to codify inequality was no doubt enhanced by a separation between the literate and the illiterate — those who used writing and those who were used by writing.

As the record above reveals, agriculture ‘worked’ by keeping a working class on a starvation diet — fed enough to till the land and harvest the crops, but too weak to rebel against the well-fed land and slave owners. Sustained and pacified with junk food and mild intoxicants — sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

And the order which assigned bountiful rewards to a few and meager provisions for everyone else was enshrined in the written word — the representation of who owned what. Whatever could be written in stone could thereafter be treated as an unalterable fact, not subject to negotiation or easy modification.

A modern echo which also evokes a sense that a dangerous power is contained in writing is offered by the West African shaman, Malidoma Patrice Somé.

At the age of four Somé was kidnapped by Jesuit missionaries who raised and educated him. When he reached twenty, he ran away and returned to his tribal village but struggled to readjust to his native culture because he was now literate. He writes:

As an educated man I had returned [unlike the by-then-common migrant worker], not as a villager who worked for the white man, but as a white man.

It all boiled down to the simple fact that I had been changed in a way unsuitable to village life, and that transformation needed to be tamed if the village was to accept me as I was. People understood my kind of literacy as the business of whites and nontribal people. Even worse, they understood literacy as an eviction of a soul from its body — the taking over of the body by another spirit. Wasn’t the white man notorious in the village for his brutality, his lack of morality and integrity? Didn’t he take without asking and kill ruthlessly? To my people, to be literate meant to be possessed by this devil of brutality. It was not harmful to know a little, but to the elders, the ability to read, however magical it appeared, was dangerous. It made the literate person the bearer of a terrible epidemic. To read was to participate in an alien form of magic that was destructive to the tribe.

If much earlier in human evolution, language liberated imagination, yielding a world of new possibilities, writing served primarily to restrict those possibilities through the creation of laws and codified social structures. Even now, consider who wields more power with the written word: a celebrated author or a Supreme Court justice? Creative writing goes mostly unrewarded while a lawyer can earn $1,000 an hour for producing the most turgid, mind-numbing prose.

If we want to use writing but not be used by it, we must never confuse the rigid form with its fluid content. Writing solidifies language, but the power of language resides in its constant malleability. Words should be chewed, not swallowed whole.

Lewis Lapham’s antidote to the age of BuzzFeed

Ron Rosenbaum writes: The counterrevolution has its embattled forward outpost on a genteel New York street called Irving Place, home to Lapham’s Quarterly. The street is named after Washington Irving, the 19th-century American author best known for creating the Headless Horseman in his short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” The cavalry charge that Lewis Lapham is now leading could be said to be one against headlessness — against the historically illiterate, heedless hordesmen of the digital revolution ignorant of our intellectual heritage; against the “Internet intellectuals” and hucksters of the purportedly utopian digital future who are decapitating our culture, trading in the ideas of some 3,000 years of civilization for…BuzzFeed.

Lapham, the legendary former editor of Harper’s, who, beginning in the 1970s, helped change the face of American nonfiction, has a new mission: taking on the Great Paradox of the digital age. Suddenly thanks to Google Books, JSTOR and the like, all the great thinkers of all the civilizations past and present are one or two clicks away. The great library of Alexandria, nexus of all the learning of the ancient world that burned to the ground, has risen from the ashes online. And yet — here is the paradox — the wisdom of the ages is in some ways more distant and difficult to find than ever, buried like lost treasure beneath a fathomless ocean of online ignorance and trivia that makes what is worthy and timeless more inaccessible than ever. There has been no great librarian of Alexandria, no accessible finder’s guide, until Lapham created his quarterly five years ago with the quixotic mission of serving as a highly selective search engine for the wisdom of the past.

Which is why the spartan quarters of the Quarterly remind me of the role rare and scattered monasteries of the Dark Ages played when, as the plague raged and the scarce manuscripts of classical literature were being burned, dedicated monks made it their sacred mission to preserve, copy, illuminate manuscripts that otherwise might have been lost forever.

In the back room of the Quarterly, Lapham still looks like the striking patrician beau ideal, slender and silvery at 77 in his expensive-looking suit. A sleek black silk scarf gives him the look of a still-potent mafia don (Don Quixote?) whose beautiful manners belie a stiletto-like gaze at contemporary culture. One can sense, reading Lapham’s Quarterly, that its vast array of erudition is designed to be a weapon — one would like to say a weapon of mass instruction. Though its 25,000 circulation doesn’t allow that scale of metaphor yet, it still has a vibrant web presence and it has the backing of a wide range of erudite eminences.

When I asked Lapham about the intent of his project, he replied with a line from Goethe, one of the great little-read writers he seeks to reintroduce to the conversation: “Goethe said that he who cannot draw on 3,000 years [of learning] is living hand to mouth.” Lapham’s solution to this under-nourishment: Give ’em a feast.

Each issue is a feast, so well curated — around 100 excerpts and many small squibs in issues devoted to such relevant subjects as money, war, the family and the future — that reading it is like choosing among bonbons for the brain. It’s a kind of hip-hop mash-up of human wisdom. Half the fun is figuring out the rationale of the order the Laphamites have given to the excerpts, which jump back and forth between millennia and genres: From Euripides, there’s Medea’s climactic heart-rending lament for her children in the “Family” issue. Isaac Bashevis Singer on magic in ’70s New York City. Juvenal’s filthy satire on adulterers in the “Eros” issue. In the new “Politics” issue we go from Solon in ancient Athens to the heroic murdered dissident journalist Anna Politkovskaya in 21st-century Moscow. The issue on money ranges from Karl Marx back to Aristophanes, forward to Lord Byron and Vladimir Nabokov, back to Hammurabi in 1780 B.C.

Lapham’s deeper agenda is to inject the wisdom of the ages into the roiling controversies of the day through small doses that are irresistible reading. In “Politics,” for example, I found a sound bite from Persia in 522 B.C., courtesy of Herodotus, which introduced me to a fellow named Otanes who made what may be the earliest and most eloquent case for democracy against oligarchy. And Ralph Ellison on the victims of racism and oligarchy in the 1930s.

That’s really the way to read the issues of the Quarterly. Not to try reading the latest one straight through, but order a few back issues from its website, Laphamsquarterly.org, and put them on your bedside table. Each page is an illumination of the consciousness, the culture that created you, and that is waiting to recreate you. [Continue reading…]

Video: The Slow Revolution

Remembering the great and irreplaceable, Robert Hughes: 1938-2012

Ken Tucker writes: Robert Hughes, not only one of the greatest art critics, but one of the greatest critics in any medium, has died. He was 74. The Australian-born Hughes was the art critic for Time Magazine starting in 1970, the author of the bestselling history of Australia, The Fatal Shore, and was the writer, producer, and star of one of the finest television documentaries ever aired: The Shock of the New, first broadcast in 1980.

Hughes had a rugged pug face, a resonant voice that could hypnotize you when he narrated or lectured, and was a fiercely combative critic with strong opinions about beauty, the art market, and artists’ technical skills. He had little use for an awful lot of modern art, or what he describes here, in a clip from Shock of the New, as stuff such as “a videotape of some twit from the University of Central Paranoia”:

First broadcast by the BBC and in this country on PBS, The Shock of the New was, for me, a shock on a couple of levels. I’d never seen such a forcefully argued documentary on television; I’d never heard art explained with such clarity; I’d never felt such joy absorbing invective mingled with praise emanating from such a curt, dashing fellow.

What Hughes demonstrated so effectively was that television, in the right hands (which might not be easy to find), was a medium with a much greater capacity than to merely entertain; that it could cultivate and express intelligence. Unfortunately, that capacity has never much overlapped with its even greater capacity: to turn a profit and exploit the tradable value of stupidity.

Here’s the first episode of The Shock of the New. Don’t be put off by the cheesy synthesized music accompanying the titles — in those days the state-funded BBC worked on a tight budget.

Peter Coster writes: Robert Hughes took a long time dying. Not in the Calvary Hospital in New York on Monday. That was the end of a road bearing a cross he carried from a near-fatal car crash in Western Australia.

It was as he lay broken in the wreckage 13 years ago that the art critic and historian first saw death.

This brilliant son of a transplanted Irish Catholic family that achieved so much in Australia saw Death “sitting at a desk like a banker. He made no gesture, but he opened his mouth and I looked right down his throat, which distended to become a tunnel”.

Hughes said it led to the inferno of old Christian art.

He was grievously hurt in that car crash on what seemed an empty road in the Outback when his car and another somehow collided. Had they not seen each other? Were the drivers drunk?

Close to death, on life support, Hughes endured many operations. Catholics never escape their Catholicism, and Hughes thought he experienced a descent into hell as he lay in the wreckage of his car, his flesh torn by demons.

A handsome, powerful hunk of a human being, he was reduced to a shambling wreck as he staggered on over the next 13 years to die, like Christ at Calvary.

The analogy would not have escaped him, knowing the hospital in the Bronx was where life was likely to end.

He had limped away from Australia on sticks, but as always he returned to the country that made him and of which he wrote with such honest clarity.

Australia, too, came from a hell in its convict past, as Hughes wrote in The Fatal Shore, his history of the beginnings of Australia as a convict settlement that was born anew.

Hughes was not some effete to turn his nose away from the taint of the past. But Australia was also a place he had to leave to understand by seeing the world. It was also why he returned.

He hated the Australia that hurt him, but he recovered, though not from his wounds.

The flesh was weak, but the spirit still strong. He was a crumbling figure, a broken Toby Jug, when he was signing his book on the tempestuous Spanish artist Goya while speaking at a Melbourne art gallery.

I asked what he thought of the tens of millions of dollars being splashed then by hedge-fund manipulators and art ignoramuses on the great paintings of the world.

He was in pain, not entirely from his injuries. His great head shook. His cheeks reddened. He described the billionaire buyers of art as investment as “raw” people. He might have been talking about meat. He roared that putting great art before them was “like putting a bucket of blood in front of a pack of dingoes”.

How to think

Chris Hedges writes: Cultures that endure carve out a protected space for those who question and challenge national myths. Artists, writers, poets, activists, journalists, philosophers, dancers, musicians, actors, directors and renegades must be tolerated if a culture is to be pulled back from disaster. Members of this intellectual and artistic class, who are usually not welcome in the stultifying halls of academia where mediocrity is triumphant, serve as prophets. They are dismissed, or labeled by the power elites as subversive, because they do not embrace collective self-worship. They force us to confront unexamined assumptions, ones that, if not challenged, lead to destruction. They expose the ruling elites as hollow and corrupt. They articulate the senselessness of a system built on the ideology of endless growth, ceaseless exploitation and constant expansion. They warn us about the poison of careerism and the futility of the search for happiness in the accumulation of wealth. They make us face ourselves, from the bitter reality of slavery and Jim Crow to the genocidal slaughter of Native Americans to the repression of working-class movements to the atrocities carried out in imperial wars to the assault on the ecosystem. They make us unsure of our virtue. They challenge the easy clichés we use to describe the nation—the land of the free, the greatest country on earth, the beacon of liberty—to expose our darkness, crimes and ignorance. They offer the possibility of a life of meaning and the capacity for transformation.

Human societies see what they want to see. They create national myths of identity out of a composite of historical events and fantasy. They ignore unpleasant facts that intrude on self-glorification. They trust naively in the notion of linear progress and in assured national dominance. This is what nationalism is about—lies. And if a culture loses its ability for thought and expression, if it effectively silences dissident voices, if it retreats into what Sigmund Freud called “screen memories,” those reassuring mixtures of fact and fiction, it dies. It surrenders its internal mechanism for puncturing self-delusion. It makes war on beauty and truth. It abolishes the sacred. It turns education into vocational training. It leaves us blind. And this is what has occurred. We are lost at sea in a great tempest. We do not know where we are. We do not know where we are going. And we do not know what is about to happen to us.

The psychoanalyst John Steiner calls this phenomenon “turning a blind eye.” He notes that often we have access to adequate knowledge but because it is unpleasant and disconcerting we choose unconsciously, and sometimes consciously, to ignore it. He uses the Oedipus story to make his point. He argued that Oedipus, Jocasta, Creon and the “blind” Tiresias grasped the truth, that Oedipus had killed his father and married his mother as prophesized, but they colluded to ignore it. We too, Steiner wrote, turn a blind eye to the dangers that confront us, despite the plethora of evidence that if we do not radically reconfigure our relationships to each other and the natural world, catastrophe is assured. Steiner describes a psychological truth that is deeply frightening. [Continue reading…]