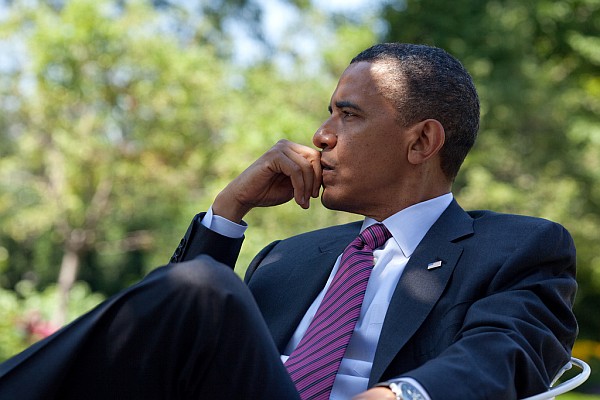

Last fall, President Obama faced criticism in the early months of his presidency during his exhaustive strategic review of the war in Afghanistan. The review had become so drawn out that his detractors claimed it presented an image of indecisiveness. Obama’s defenders responded by saying this was a process of careful and thorough deliberation from a commander in chief who, unlike his predecessor, had the interest and ability to think things through. If Bush was the decider, Obama was the studious deliberator.

The conclusion of those deliberations was less than impressive. Obama took the only idea that for Bush had acquired some brand value, on the assumption it could sell the war in Afghanistan just as it had helped rejuvenate the saleability of the war in Iraq. Obama followed what has become an American presidential tradition, which is to say, when you don’t know where you’re heading, move forward. Escalate the war — but give escalation a palatable name with the Viagra of American war-making: a surge.

This time around, with no counterpart to Iraq’s Sons of the Awakening offering a helping hand, the Pentagon’s latest efforts to prove the war is not being lost have been so unconvincing that the best face the US can now present is to say, “nobody is winning.”

Tom Engelhardt writes:

To all appearances, when it comes to the administration’s two South Asian wars, one open, one more hidden, Obama and his top officials are flailing around. They are evidently trying whatever comes to mind in much the manner of the oil company BP as it repeatedly fails to cap a demolished oil well 5,000 feet under the waves in the Gulf of Mexico. In a sense, when it comes to Washington’s ability to control the situation, Pakistan and Afghanistan might as well be 5,000 feet underwater. Like BP, Obama’s officials, military and civilian, seem to be operating in the dark, using unmanned robotic vehicles. And as in the Gulf, after each new failure, the destruction only spreads.

For all the policy reviews and shuttling officials, the surging troops, extra private contractors, and new bases, Obama’s wars are worsening. Lacking is any coherent regional policy or semblance of real strategy — counterinsurgency being only a method of fighting and a set of tactics for doing so. In place of strategic coherence there is just one knee-jerk response: escalation. As unexpected events grip the Obama administration by the throat, its officials increasingly act as if further escalation were their only choice, their fated choice.

This response is eerily familiar. It permeated Washington’s mentality in the Vietnam War years. In fact, one of the strangest aspects of that war was the way America’s leaders — including President Lyndon Johnson — felt increasingly helpless and hopeless even as they committed themselves to further steps up the ladder of escalation.

The hallmark of a floundering wartime leader is the extent to which whatever he says begins to ring hollow. Jeremy Scahill picked up on one such declaration last week.

During his White House press conference Wednesday with Afghan President Hamid Karzai, President Obama addressed the issue of civilian deaths caused by US operations in Afghanistan. “I take no pleasure in hearing a report that a civilian has been killed,” said Obama. “That’s not why I ran for president, that’s not why I’m Commander in Chief.”

“Let me be very clear about what I told President Karazi: When there is a civilian casualty, that is not just a political problem for me. I am ultimately accountable, just as Gen. McChrystal is accountable, for somebody who is not on the battlefield who got killed,” said Obama.

That statement is quite remarkable for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it is not true. How are President Obama or Gen. McChrystal accountable? Afghans have little, if any, recourse for civilian deaths. They cannot press their case in international courts because the US doesn’t recognize an International Criminal Court with jurisdiction over US forces, Afghan courts have not and will not be given jurisdiction and Attorney General Eric Holder has made clear that the Justice Department will not permit cases against US military officials brought by foreign victims to proceed in US courts. So, what does it mean to be accountable for civilian deaths? Public apology? Press conferences? A handful of courts martial?

Meanwhile, David Ignatius remains convinced that the administration has some kind of strategic process in operation, but with his eyes set on the endgame, he suggests:

As the White House prepares its reconciliation strategy, it should ponder the Pashtun culture that spawned the Taliban insurgency. The United States has often lacked this sense of cultural nuance, which is why we have made so many mistakes in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

One thing that should be obvious by now is that you don’t make much progress with Pashtun leaders by slapping them around in public. This is a culture that prizes dignity and detests humiliation. Attempts to shame people into capitulation usually backfire.

And in which culture is dignity not prized and humiliation tolerated?

Ignatius is correct in suggesting that Washington needs to understand Pashtun culture — though that recommendation might have been more timely if delivered with some force nine years ago. But America’s problem consists equally in a lack of cultural self-awareness.

In a culture so deeply molded by what I will call the advertising gestalt, America’s most crippling deficit is a pervasive lack of interest in distinguishing between appearance and reality. Military campaigns have been turned into marketing campaigns viewed with the uncritical attention that attends most commercial communication.

“We’ve got a government in a box, ready to roll in,” General Stanley McChrystal said on the eve of the Marja offensive. Billed as a “clear and hold” operation, the combat phase was declared a success at the end of February.

As has so often proved to be the case, the American declaration of victory turned out to be premature, McChrystal’s government in a box never got delivered and most of the clearing now taking place is by families clearing out of the battlefield.

Carlotta Gall, reporting from Lashkar Gah, says:

Marja residents arriving here last week, many looking bleak and shell-shocked, said civilians had been trapped by the fighting, running a gantlet of mines laid by insurgents and firefights around government and coalition positions. The pervasive Taliban presence forbids them from having any contact with or taking assistance from the government or coalition forces.

“People are leaving; you see 10 to 20 families each day on the road who are leaving Marja due to insecurity,” said a farmer, Abdul Rahman, 52, who was traveling on his own. “It is now hard to live there in this situation.”

One farmer who was loading his family and belongings onto a tractor-trailer on the edge of Lashkar Gah last week said he had abandoned his whole livelihood in Sistan, Marja, as soon as the harvest, a poor one this year, was done.

“Every day they were fighting and shelling,” said the farmer, Abdul Malook Aka, 55. “We do not feel secure in the village and we decided to leave. Security is getting worse day by day.”

“We thought security would be improving,” he said.

Those who remain in Marja voiced similar complaints in dozens of interviews and repeated visits to Marja over the last month.

“I am sure if I stay in Marja I will be killed one day either by Taliban or the Americans,” said Mir Hamza, 40, a farmer from Loye Charah.

Victory over the Taliban in Marja was supposed to be a prelude to forcing the insurgency out of its largest stronghold, Kandahar. But in light of the indecisive outcome of the earlier operation, US officials are back-pedaling hard in an effort to diminish expectations about what the much larger operation is meant to accomplish. And as they do so, the Taliban have mounted an assassination campaign which guarantees that this time around neither McChrystal nor anyone else will be making any idle promises about early success.

The Los Angeles Times reports:

In recent weeks, Western military officials in Afghanistan have stopped referring to the Kandahar campaign as an offensive.

“What we plan on is mainly an Afghan, politically led process … where you have slowly incremental changes of security, which enables governance and development,” said Army Col. Wayne Shanks, the chief public affairs officer for NATO’s International Security Assistance Force. “So this is not going to be anything that is immediate or quick.”

Such talk leaves many Kandaharis baffled. Rangina Hamidi, who runs a handicraft business that employs Afghan village women in Kandahar province, said it was difficult for local people to understand why the North Atlantic Treaty Organization began talking publicly months ago about Kandahar being the next big target for Western forces.

“Most of the women I work with are illiterate and hardly ever leave their homes — they are not involved in public life,” Hamidi said. “But even these women are saying, ‘If you are going to do an offensive, why are you going to announce it in advance?'”

As U.S. officials seek to emphasize the campaign’s political goals rather than its military ones, insurgent assassins are systematically targeting precisely the kind of people on whom Western planners are relying to help woo the populace to the side of the Afghan government: tribal elders, municipal employees, security officials, aid workers and others.

After an exchange between the UAE ambassador to the US Yousef al-Otaiba and Jeffrey Goldberg on Tuesday we learn that “the UAE would sooner see military action against Iran’s nuclear program than see the program succeed” — at least that’s what Goldberg says.

After an exchange between the UAE ambassador to the US Yousef al-Otaiba and Jeffrey Goldberg on Tuesday we learn that “the UAE would sooner see military action against Iran’s nuclear program than see the program succeed” — at least that’s what Goldberg says.

Every disaster gets a name — Katrina, Exxon Valdez, The Tsunami — and now The Spill?

Every disaster gets a name — Katrina, Exxon Valdez, The Tsunami — and now The Spill?

I claim no special knowledge of the inside workings of the Obama administration — merely an ear that notes the difference between substance and flatulence and to

I claim no special knowledge of the inside workings of the Obama administration — merely an ear that notes the difference between substance and flatulence and to