The Wall Street Journal reports: At Hospital 601, not far from the presidential palace in Damascus, Syrian guards ran out of space to store the dead and had to use an adjoining warehouse where military vehicles were repaired.

A forensic photographer working for Syria’s military police walked the rows and took pictures of the emaciated and disfigured corpses, most believed to be anti-Assad activists. Numbers written on the bodies and on white cards, the photographer said, told regime bureaucrats the identities of the deceased, when they died and which branch of the Syrian security services had held them.

U.S. investigators who have reviewed many of the photos say they believe at least 10,000 corpses were cataloged this way between 2011 and mid-2013. Investigators believe they weren’t victims of regular warfare but of torture, and that the bodies were brought to the hospital from the Assad regime’s sprawling network of prisons. They were told some appeared to have died on site.

Last year, the Syrian military-police photographer defected to the West. Investigators later gave him the code name Caesar to disguise his identity. He turned over to U.S. law-enforcement agencies earlier this year a vast trove of postmortem photographs from Hospital 601 that he and other military photographers took over the two-year period, which he helped smuggle out of the country on digital thumb drives.

Over the ensuing months, U.S. investigators pored over the photos, which depicted the deaths and the elaborate counting system, and started to debrief Caesar and other activists involved in his defection. U.S. and European investigators have since concluded not only that the images were genuine, but that they offered the best evidence to date of an industrial-scale campaign by the government of Bashar al-Assad against its political opponents. U.S. Ambassador-at-large Stephen Rapp, head of the State Department’s Office of Global Criminal Justice, has compared the pattern to some of the most notorious acts of mass murder of the past century.

This account, based on interviews with war-crimes investigators in the U.S. and Europe, more than a dozen defectors, and opposition leaders working with Caesar, provides fresh details about Syria’s crackdown on its political opponents and the central role of Hospital 601 in processing bodies and documenting the deaths for the government.

Investigators haven’t finished analyzing the entire cache of photographs and are still trying to gather evidence to fully understand the regime’s role in the deaths. Prosecutors must be careful about jumping to conclusions before all the evidence is in, cautioned a senior U.S. official, who noted that investigators are far from finished debriefing Caesar.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation unit that investigates genocide and war crimes, and other agencies, hope to soon get a more detailed account of what happened at Hospital 601 from Caesar, officials said. Some U.S. officials want to use Caesar’s photographs, which show bodies that appear to have been strangled, beaten or disfigured, to build a case for a potential war-crimes prosecution of the Assad regime. It is unclear when, if ever, such a case might be brought. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Feature

Why John Kerry’s Israel-Palestine peace plan failed

The New Republic reports: The depth of Palestinian alienation became clear to Kerry and his team only on February 19, when the two sides met for dinner at Le Maurice Hotel in Paris — the kickoff to a three-day parley. As the Palestinians walked in the door, each American was struck with the same thought: These guys do not look like they’re in a good mood. Following dinner, Kerry met alone with Abbas while [the Palestinians’ chief negotiator Saeb] Erekat and [Kerry’s envoy to the talks, Martin] Indyk spoke in a separate room. Afterward, Kerry and Indyk got in the car that would take them to their rooms at the Grande Hotel. The secretary turned to his envoy: “That was really negative.” At around the same time, Abbas, who was nursing a terrible cold, saw Erekat in the hall and told him that he was going straight to sleep. “It was a difficult meeting,” he said. “I’ll brief you tomorrow.”

The next morning, at around 7:30, Indyk called Erekat. “The secretary wants to see you,” he said. Erekat was surprised at the early time of the summons. This must be important. He put on a suit and took a cab to the Grande. When he and Indyk got to Kerry’s Louis XIII-style suite, the secretary answered the door. He was dressed casually: hotel slippers, no jacket or tie. He looked concerned. After a moment of silence, the first words came out of Kerry’s mouth. “Why is Abu Mazen so angry with me?”

Erekat responded that he hadn’t yet been briefed on the meeting, so Kerry offered to get his notes. “I barely said a word, and he started saying, ‘I cannot accept this,’” Kerry grumbled, going through some of Abbas’s red lines.

“What do you want?” Erekat said. “These are his positions. We are sick and tired of Bibi the Great. He’s taking you for a ride.”

“No one takes me for a ride!”

“He is refusing to negotiate on a map or even say 1967.”

“I’ve moved him,” Kerry said, “I’ve moved him.”

“Where?” Erekat said, raising his voice. “Show me! This is just the impression he’s giving you.”

The next month, Abbas led a Palestinian delegation to Washington. At a March 16 lunch at Kerry’s Georgetown home, the secretary asked Abbas if he’d accept delaying the fourth prisoner release by a few days. Kerry was worried that the Israelis were wavering. “No,” Abbas said. “I cannot do this.” Abbas would later describe that moment as a turning point. If the Americans can’t convince Israel to give me 26 prisoners, he thought then, how will they ever get them to give me East Jerusalem? At the meal, Erekat noticed Abbas displaying some of his telltale signs of discomfort. He was crossing his legs, looking over at him every two minutes. The index cards on which he normally took notes had been placed back in his suit pocket. Abbas was no longer interested in what was being said.

The next day at the White House, Obama tried his luck with the Palestinian leader. He reviewed the latest American proposals, some of which had been tilted in Abbas’s direction. (The document would now state categorically that there would be a Palestinian capital in Jerusalem.) “Don’t quibble with this detail or that detail,” Obama said. “The occupation will end. You will get a Palestinian state. You will never have an administration as committed to that as this one.” Abbas and Erekat were not impressed.

After the meeting, the Palestinian negotiator saw Susan Rice — Abbas’s favorite member of the Obama administration — in the hall. “Susan,” he said, “I see we’ve yet to succeed in making it clear to you that we Palestinians aren’t stupid.” Rice couldn’t believe it. “You Palestinians,” she told him, “can never see the fucking big picture.” [Continue reading…]

How Russian hackers stole the Nasdaq

Bloomberg Businessweek reports: In October 2010, a Federal Bureau of Investigation system monitoring U.S. Internet traffic picked up an alert. The signal was coming from Nasdaq. It looked like malware had snuck into the company’s central servers. There were indications that the intruder was not a kid somewhere, but the intelligence agency of another country. More troubling still: When the U.S. experts got a better look at the malware, they realized it was attack code, designed to cause damage.

As much as hacking has become a daily irritant, much more of it crosses watch-center monitors out of sight from the public. The Chinese, the French, the Israelis — and many less well known or understood players — all hack in one way or another. They steal missile plans, chemical formulas, power-plant pipeline schematics, and economic data. That’s espionage; attack code is a military strike. There are only a few recorded deployments, the most famous being the Stuxnet worm. Widely believed to be a joint project of the U.S. and Israel, Stuxnet temporarily disabled Iran’s uranium-processing facility at Natanz in 2010. It switched off safety mechanisms, causing the centrifuges at the heart of a refinery to spin out of control. Two years later, Iran destroyed two-thirds of Saudi Aramco’s computer network with a relatively unsophisticated but fast-spreading “wiper” virus. One veteran U.S. official says that when it came to a digital weapon planted in a critical system inside the U.S., he’s seen it only once — in Nasdaq.

The October alert prompted the involvement of the National Security Agency, and just into 2011, the NSA concluded there was a significant danger. A crisis action team convened via secure videoconference in a briefing room in an 11-story office building in the Washington suburbs. Besides a fondue restaurant and a CrossFit gym, the building is home to the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC), whose mission is to spot and coordinate the government’s response to digital attacks on the U.S. They reviewed the FBI data and additional information from the NSA, and quickly concluded they needed to escalate.

Thus began a frenzied five-month investigation that would test the cyber-response capabilities of the U.S. and directly involve the president. Intelligence and law enforcement agencies, under pressure to decipher a complex hack, struggled to provide an even moderately clear picture to policymakers. After months of work, there were still basic disagreements in different parts of government over who was behind the incident and why. “We’ve seen a nation-state gain access to at least one of our stock exchanges, I’ll put it that way, and it’s not crystal clear what their final objective is,” says House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Rogers, a Republican from Michigan, who agreed to talk about the incident only in general terms because the details remain classified. “The bad news of that equation is, I’m not sure you will really know until that final trigger is pulled. And you never want to get to that.”

Bloomberg Businessweek spent several months interviewing more than two dozen people about the Nasdaq attack and its aftermath, which has never been fully reported. Nine of those people were directly involved in the investigation and national security deliberations; none were authorized to speak on the record. “The investigation into the Nasdaq intrusion is an ongoing matter,” says FBI New York Assistant Director in Charge George Venizelos. “Like all cyber cases, it’s complex and involves evidence and facts that evolve over time.”

While the hack was successfully disrupted, it revealed how vulnerable financial exchanges—as well as banks, chemical refineries, water plants, and electric utilities—are to digital assault. One official who experienced the event firsthand says he thought the attack would change everything, that it would force the U.S. to get serious about preparing for a new era of conflict by computer. He was wrong. [Continue reading…]

I, spy: Edward Snowden in exile

The Guardian reports: Fiction and films, the nearest most of us knowingly get to the world of espionage, give us a series of reliable stereotypes. British spies are hard-bitten, libidinous he-men. Russian agents are thickset, low-browed and facially scarred. And defectors end up as tragic old soaks in Moscow, scanning old copies of the Times for news of the Test match.

Such a fate was anticipated for Edward Snowden by Michael Hayden, a former NSA and CIA chief, who predicted last September that the former NSA analyst would be stranded in Moscow for the rest of his days – “isolated, bored, lonely, depressed… and alcoholic”.

But the Edward Snowden who materialises in our hotel room shortly after noon on the appointed day seems none of those things. A year into his exile in Moscow, he feels less, not more, isolated. If he is depressed, he doesn’t show it. And, at the end of seven hours of conversation, he refuses a beer. “I actually don’t drink.” He smiles when repeating Hayden’s jibe. “I was like, wow, their intelligence is worse than I thought.”

Oliver Stone, who is working on a film about the man now standing in room 615 of the Golden Apple hotel on Moscow’s Malaya Dmitrovka, might struggle to make his subject live up to the canon of great movie spies. The American director has visited Snowden in Moscow, and wants to portray him as an out-and-out hero, but he is an unconventional one: quiet, disciplined, unshowy, almost academic in his speech. If Snowden has vices – and God knows they must have been looking for them – none has emerged in the 13 months since he slipped away from his life as a contracted NSA analyst in Hawaii, intent on sharing the biggest cache of top-secret material the world has ever seen.

Since arriving in Moscow, Snowden has been keeping late and solitary hours – effectively living on US time, tapping away on one of his three computers (three to be safe; he uses encrypted chat, too). If anything, he appears more connected and outgoing than he could be in his former life as an agent. Of his life now, he says, “There’s actually not that much difference. You know, I think there are guys who are just hoping to see me sad. And they’re going to continue to be disappointed.” [Continue reading…]

When chance surpasses reason

Michael Schulson writes: In the 1970s, a young American anthropologist named Michael Dove set out for Indonesia, intending to solve an ethnographic mystery. Then a graduate student at Stanford, Dove had been reading about the Kantu’, a group of subsistence farmers who live in the tropical forests of Borneo. The Kantu’ practise the kind of shifting agriculture known to anthropologists as swidden farming, and to everyone else as slash-and-burn. Swidden farmers usually grow crops in nutrient-poor soil. They use fire to clear their fields, which they abandon at the end of each growing season.

Like other swidden farmers, the Kantu’ would establish new farming sites ever year in which to grow rice and other crops. Unlike most other swidden farmers, the Kantu’ choose where to place these fields through a ritualised form of birdwatching. They believe that certain species of bird – the Scarlet-rumped Trogon, the Rufous Piculet, and five others – are the sons-in-law of God. The appearances of these birds guide the affairs of human beings. So, in order to select a site for cultivation, a Kantu’ farmer would walk through the forest until he spotted the right combination of omen birds. And there he would clear a field and plant his crops.

Dove figured that the birds must be serving as some kind of ecological indicator. Perhaps they gravitated toward good soil, or smaller trees, or some other useful characteristic of a swidden site. After all, the Kantu’ had been using bird augury for generations, and they hadn’t starved yet. The birds, Dove assumed, had to be telling the Kantu’ something about the land. But neither he, nor any other anthropologist, had any notion of what that something was.

He followed Kantu’ augurers. He watched omen birds. He measured the size of each household’s harvest. And he became more and more confused. Kantu’ augury is so intricate, so dependent on slight alterations and is-the-bird-to-my-left-or-my-right contingencies that Dove soon found there was no discernible correlation at all between Piculets and Trogons and the success of a Kantu’ crop. The augurers he was shadowing, Dove told me, ‘looked more and more like people who were rolling dice’. [Continue reading…]

Kurdish independence: Harder than it looks

Joost Hiltermann writes: The jihadist blitz through northwestern Iraq has ended the fragile peace that was established after the 2007-2008 US surge. It has cast grave doubt on the basic capacity of the Iraqi army—reconstituted, trained and equipped at great expense by Washington—to control the country, and it could bring down the government of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, whose eight-year reign has been marred by mismanagement and sectarian polarization. But for Iraqi Kurds, the offensive by the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) and other groups has offered a dramatic opportunity: a chance to expand their own influence beyond Iraqi Kurdistan and take possession of other parts of northern Iraq they’ve long claimed as theirs.

At the heart of these “disputed areas” is the strategic city of Kirkuk, which the disciplined and highly motivated Kurdish Peshmerga took over in mid-June, after Iraqi soldiers stationed there fled in fear of advancing jihadists. A charmless city of slightly less than one million people, Kirkuk betrays little of its past as an important Ottoman garrison town. The desolate ruin of an ancient citadel, sitting on a mound overlooking the dried-out Khasa River, is one of the few hints of the city’s earlier glory. Yet Kirkuk lies on top of one of Iraq’s largest oil fields, and with its crucial location directly adjacent to the Kurdish region, the city is the prize in the Kurds’ long journey to independence, a town they call their Jerusalem. When their Peshmerga fighters easily took over a few weeks ago, there was loud rejoicing throughout the Kurdish land.

But while the Kurds believe Kirkuk’s riches give them crucial economic foundations for a sustainable independent state, the city’s ethnic heterogeneity raises serious questions about their claims to it. Not only is Kirkuk’s population—as with that of many other Iraqi cities, including Baghdad itself—deeply intermixed. The disputed status of its vast oil field also stands as a major obstacle to any attempt to divide the country’s oil revenues equitably. To anyone who advocates dividing Iraq into neat ethnic and sectarian groups, Kirkuk shows just how challenging that would be in practice. [Continue reading…]

Iraq illusions

Jessica T. Mathews writes: The story most media accounts tell of the recent burst of violence in Iraq seems clear-cut and straightforward. In reality, what is happening is anything but. The Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), so the narrative goes, a barbaric, jihadi militia, honed in combat in Syria, has swept aside vastly larger but feckless Iraqi army forces in a seemingly unstoppable tide of conquest across northern and western Iraq, almost to the outskirts of Baghdad. The country, riven by ineluctable sectarian conflict, stands on the brink of civil war. The United States, which left Iraq too soon, now has to act fast, choosing among an array of ugly options, among them renewed military involvement and making common cause with Iran. Alternatives include watching Iraq splinter and the creation of an Islamist caliphate spanning eastern Syria and western Iraq.

Much of this is, at best, misleading; some is outright wrong. ISIS, to begin, is only one of an almost uncountable mélange of Sunni militant groups. Besides ISIS, the Sunni insurgency that has risen up against the government of Nouri al-Maliki includes another jihadi group, Ansar al-Islam (Supporters of Islam), as well as the Military Council of the Tribes of Iraq, comprising as many as eighty tribes, and the Army of the Men of the Naqshbandi Order, a group that claims to have Shiite and Kurdish members and certainly includes many Sunni Baathists once loyal to Saddam Hussein.

This is a partial list. The important point is that within the forces that have proven so powerful in recent weeks are groups with profound differences, even mutual hatred. ISIS, for example, has turned on al-Qaeda, its parent, for being too moderate, and considers Baathists to be infidels. These disparate groups are fighting together now, yes, but they won’t be together for long. And they have been fighting in places where local populations are friendly to them. It will be a different matter when they meet the tough and motivated Kurdish peshmerga or Shiite forces in the Shiites’ own regions.

The story, which has seemed to be all about religion and military developments, is actually mostly about politics: access to government revenue and services, a say in decision-making, and a modicum of social justice. True, one side is Sunni and the other Shia, but this is not a theological conflict rooted in the seventh century. ISIS and its allies have triumphed because the Sunni populations of Mosul and Tikrit and Fallujah have welcomed and supported them—not because of ISIS’s disgusting behavior, but in spite of it. The Sunnis in these towns are more afraid of what their government may do to them than of what the Sunni militia might. They have had enough of years of being marginalized while suffering vicious repression, lawlessness, and rampant corruption at the hands of Iraq’s Shia-led government.

What is happening now—not its details, but its essentials—was clearly evident at the time of President Bush’s “surge” seven years ago. The premise for the added American troops then was that insecurity in Iraq blocked political reconciliation. If the violence could be reduced, the administration argued, reconciliation would follow—but it didn’t. The important agreements on the eighteen political “benchmarks” specified by the US never were carried out and haven’t been to this day. (They included, for example, laws that were supposed to distribute oil revenue equitably and reverse the purge of Baathists from government.) When a government is wrenched apart, especially an authoritarian one, a struggle for political power immediately fills the vacuum. In Iraq the struggle has been, and continues to be, within sectarian groups almost as much as between them. [Continue reading…]

The mood in Baghdad

Patrick Cockburn writes: In early June, Abbas Saddam, a private soldier from a Shia district in Baghdad serving in the 11th Division of the Iraqi army, was transferred from Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province in western Iraq, to Mosul in the north. The fighting started not long after he got there. But on the morning of 10 June the commanding officer told his men to stop shooting, hand over their rifles to the insurgents, take off their uniforms and get out of the city. Before they could obey, their barracks were invaded by a crowd of civilians. ‘They threw stones at us,’ Abbas recalled, ‘and shouted: “We don’t want you in our city! You are Maliki’s sons! You are the sons of mutta! You are Safavids! You are the army of Iran!”’

The crowd’s attack on the soldiers shows that the fall of Mosul was the result of a popular uprising as well as a military assault by Isis. The Iraqi army was detested as a foreign occupying force of Shia soldiers, regarded in Mosul – an overwhelmingly Sunni city – as creatures of an Iranian puppet regime led by Nouri al-Maliki. Abbas says there were Isis fighters – always called Daash in Iraq after the Arabic acronym of their name – mixed in with the crowd. They said to the soldiers: ‘You guys are OK: just put up your rifles and go. If you don’t, we’ll kill you.’ Abbas saw women and children with military weapons; local people offered the soldiers dishdashes to replace their uniforms so that they could flee. He made his way back to his family in Baghdad, but he hasn’t told the army he’s here because he’s afraid of being put on trial for desertion, as happened to a friend. He feels this is deeply unjust: after all, he says, it was his officers who ordered him to give up his weapon and uniform. He asks why Generals Ali Ghaidan Majid, commander of ground forces, and Abboud Qanbar, deputy chief of staff, who fled Mosul for Kurdistan in civilian clothes at the same time, haven’t been ‘judged and executed as traitors’.

Shock at the disintegration of the army in Mosul and other Sunni-majority districts of northern Iraq is still determining the mood in Baghdad weeks later. The debacle marks the end of a distinct period in Iraqi history: the period between 2006 and 2014 when the Iraqi Shia under Maliki sought to dominate the country much as the Sunni had done under Saddam Hussein. The Shias’ feeling of disempowerment after the Mosul collapse has been so unexpected that they believe almost any other disaster is possible. [Continue reading…]

The Nazi interrogator who revealed the value of kindness

Eric Horowitz writes: The downed World War II fighter pilot had little reason to be wary. Thus far, his German interrogator had seemed uninterested in extracting military intelligence, and had acted with genuine kindness. He made friendly conversation, shared some of his wife’s delicious baked goods, and took the pilot out for a lovely stroll in the German countryside. So when the interrogator erroneously suggested that a chemical shortage was responsible for American tracer bullets leaving white rather than red smoke, the pilot quickly corrected him with the information German commanders sought. No, there was no chemical shortage; the white smoke was supposed to signal to pilots that they would soon be out of ammunition.

The man prying the information loose was Hanns Scharff, and as Raymond Tolliver chronicles in The Interrogator: The Story of Hanns Joachim Scharff, Master Interrogator of the Luftwaffe, Scharff’s unparalleled success did not come from confrontation or threats, but from simply being nice. With the morality and efficacy of interrogation practices coming under increasing scrutiny, Scharff’s techniques — and questions about the extent to which they work — are taking on greater significance.

The fact that Scharff is even mentioned in criminal justice circles is a historical anomaly. Not only was he never meant be an interrogator, he was never meant to be in the German military at all. In the decade leading up to the war Scharff worked as a businessman in Johannesburg, where he lived with his British wife and two kids. Not exactly a portrait of the threatening Axis enemy Captain America was created to battle. [Continue reading…]

In a grain, a glimpse of the cosmos

Natalie Wolchover writes: One January afternoon five years ago, Princeton geologist Lincoln Hollister opened an email from a colleague he’d never met bearing the subject line, “Help! Help! Help!” Paul Steinhardt, a theoretical physicist and the director of Princeton’s Center for Theoretical Science, wrote that he had an extraordinary rock on his hands, one that he thought was natural but whose origin and formation he could not identify. Hollister had examined tons of obscure rocks over his five-decade career and agreed to take a look.

Originally a dense grain two or three millimeters across that had been ground down into microscopic fragments, the rock was a mishmash of lustrous metal and matte mineral of a yellowish hue. It reminded Hollister of something from Oregon called josephinite. He told Steinhardt that such rocks typically form deep underground at the boundary between Earth’s core and mantle or near the surface due to a particular weathering phenomenon. “Of course, all of that ended up being a false path,” said Hollister, 75. The more the scientists studied the rock, the stranger it seemed.

After five years, approximately 5,000 Steinhardt-Hollister emails and a treacherous journey to the barren arctic tundra of northeastern Russia, the mystery has only deepened. Today, Steinhardt, Hollister and 15 collaborators reported the curious results of a long and improbable detective story. Their findings, detailed in the journal Nature Communications, reveal new aspects of the solar system as it was 4.5 billion years ago: chunks of incongruous metal inexplicably orbiting the newborn sun, a collision of extraordinary magnitude, and the creation of new minerals, including an entire class of matter never before seen in nature. It’s a drama etched in the geochemistry of a truly singular rock. [Continue reading…]

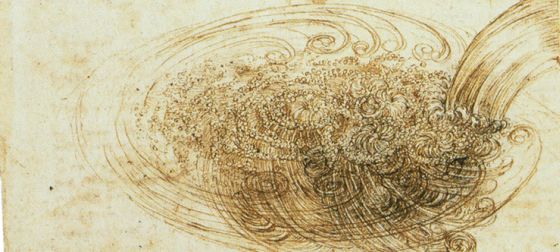

To understand turbulence we need the intuitive perspective of art

Philip Ball writes: When the German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld assigned his most brilliant student a subject for his doctoral thesis in 1923, he admitted that “I would not have proposed a topic of this difficulty to any of my other pupils.” Those others included such geniuses as Wolfgang Pauli and Hans Bethe, yet for Sommerfeld the only one who was up to the challenge of this subject was Werner Heisenberg.

Heisenberg went on to be a key founder of quantum theory and was awarded the 1932 Nobel Prize in physics. He developed one of the first mathematical descriptions of this new and revolutionary discipline, discovered the uncertainty principle, and together with Niels Bohr engineered the “Copenhagen interpretation” of quantum theory, to which many physicists still adhere today.

The subject of Heisenberg’s doctoral dissertation, however, wasn’t quantum physics. It was harder than that. The 59-page calculation that he submitted to the faculty of the University of Munich in 1923 was titled “On the stability and turbulence of fluid flow.”

Sommerfeld had been contacted by the Isar Company of Munich, which was contracted to prevent the Isar River from flooding by building up its banks. The company wanted to know at what point the river flow changed from being smooth (the technical term is “laminar”) to being turbulent, beset with eddies. That question requires some understanding of what turbulence is. Heisenberg’s work on the problem was impressive—he solved the mathematical equations of flow at the point of the laminar-to-turbulent change—and it stimulated ideas for decades afterward. But he didn’t really crack it—he couldn’t construct a comprehensive theory of turbulence.

Heisenberg was not given to modesty, but it seems he had no illusions about his achievements here. One popular story goes that he once said, “When I meet God, I am going to ask him two questions. Why relativity? And why turbulence? I really believe he will have an answer for the first.”

It is probably an apocryphal tale. The same remark has been attributed to at least one other person: The British mathematician and expert on fluid flow, Horace Lamb, is said to have hoped that God might enlighten him on quantum electrodynamics and turbulence, saying that “about the former I am rather optimistic.”

You get the point: turbulence, a ubiquitous and eminently practical problem in the real world, is frighteningly hard to understand. [Continue reading…]

Climate: Will we lose the endgame?

Bill McKibben writes: We may be entering the high-stakes endgame on climate change. The pieces — technological and perhaps political –are finally in place for rapid, powerful action to shift us off of fossil fuel. Unfortunately, the players may well decide instead to simply move pawns back and forth for another couple of decades, which would be fatal. Even more unfortunately, the natural world is daily making it more clear that the clock ticks down faster than we feared. The whole game is very nearly in check.

Let us begin in Antarctica, the least-populated continent, and the one most nearly unchanged by humans. In her book about the region, Gabrielle Walker describes very well current activities on the vast ice sheet, from the constant discovery of new undersea life to the ongoing hunt for meteorites, which are relatively easy to track down on the white ice. For anyone who has ever wondered what it’s like to winter at 70 degrees below zero, her account will be telling. She quotes Sarah Krall, who worked in the air control center for the continent, coordinating flights and serving as “the voice of Antarctica.” From her first view of the landscape, Krall says, she was captivated:

I felt like I had no place to put it…. It was so big, so beautiful. I thought it might seem bare, but that b word didn’t occur to me. Antarctica was just too full of itself.

Describing her walk around the rim of Mount Erebus, the most southerly active volcano on the planet, Krall adds: “It’s visceral. This land makes me feel small. Not diminished, but small. I like that.”

In another sense, though, Antarctica is where we really learned how big we are, if not as individuals then as a species. [Continue reading…]

Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS, Assad, and the Syrian revolution

Rania Abouzeid writes: The eight men, beards trimmed, explosive belts fastened, pistols and grenades concealed in their clothing, waited until nightfall before stealing across the flat, porous Iraqi border. They navigated the berms and trenches along the frontier, traversing two-way smuggling routes used to ferry cigarettes, livestock, weapons — and jihadis to enter the northeastern Syrian province of Hasaka. It was August 2011, the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, and Syria was five months into a still largely peaceful uprising against President Bashar al-Assad.

Their leader was a Syrian emissary from the al Qaeda affiliate forged in the bloody conflict next door. He called himself Abu Mohammad al-Golani, and the young fighter, about whom little is known for sure except that he is a veteran of that war against the Americans in Iraq, had been authorized by his boss, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and al Qaeda’s central command to set up a Syrian offshoot of the notorious group. His mission, made clear in subsequent public statements, was nothing less than to bring down the Assad regime and establish an Islamic state in its place. No one knew it at the time, but that trip across the border would turn out to be a crucial turning point in the Syrian civil war, a key factor in the metastasizing of an internal conflict into a regional conflagration that now threatens the regime in Iraq as well as Syria.

Before Golani’s nighttime trek from Iraq into Syria, al Qaeda was looking increasingly like a spent force. Osama bin Laden had been killed a few months earlier. His successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, had bin Laden’s passion but little of his charisma, and the Middle East was still in the throes of the so-called Arab Spring, experimenting with peaceful protests rather than violence as a means to bring about change.

But over the next few years, at times even aided by the cynical Assad regime, Golani would rejuvenate the al Qaeda brand and establish a firm base in Syria. His group, called Jabhat al-Nusra l’Ahl as-Sham (meaning Support Front for the People of the Sham, an Arabic term encompassing Damascus, Syria and the Levant), would create a whole new generation of jihadists from around the Islamic world, fighters who have become a crucial force in a Syrian civil war that has claimed well over 140,000 lives and displaced nine million Syrians, both internally and into neighboring countries.

Just as dangerously, Nusra’s very success would create a massive rift with its jihadist parent organization, the al Qaeda affiliate known as the Islamic State of Iraq. By April of 2013, that group would rebrand itself as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, or ISIL, a new name that indicated its transnational ambitions. By this June, ISIL (also known as ISIS) had become so powerful that it would brazenly undertake a blitzkrieg-like advance across northern and western Iraq, rapidly capturing the Iraqi cities of Mosul and Tikrit and underscoring the seeming irrelevance of Zawahiri and the old al Qaeda leadership, somewhere in hiding off in South Asia, far from the newest jihadi battlefields.

Now, as a result of ISIL’s victories, U.S. President Barack Obama, a man who campaigned on extricating the United States from “dumb” wars in the Middle East, finds himself potentially embroiled in another one. He is sending a small contingent of special forces to work with the Iraqi military, but many in Washington are urging him to take more decisive action against the ISIL militants sweeping across Iraq, seizing territory and oil facilities and threatening to sow chaos in Baghdad and beyond.

This was not inevitable. The Syrian revolution—and the hesitant, confused international reaction to it—paved the way for the resurrection of a militant Islam that would turn vast regions of Iraq and Syria into borderless jihadi strongholds and inch closer to redrawing the map of the Middle East—in practical terms if not on paper. This is the story, pieced together over several trips into Syria and rare interviews with highly placed jihadi commanders on the front lines, of how it happened. [Continue reading…]

Israel has Egypt over a barrel

David Hearst writes: It took the CIA 60 years to admit its involvement in the overthrow of Mohammad Mossadeq, Iran’s first democratically elected prime minister. The circumstances around the overthrow of Egypt’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, may not take as long to come to light, regardless of whom is behind it.

Mossadeq sealed his fate when he renationalized Iran’s oil production, which had been under the control of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, later to become BP. Morsi’s enemy was gas, and he proved to be a major obstacle to a lucrative deal with Israel – which nobody will be surprised to learn – is about to take place now he has been removed.

Clayton Swisher of Al Jazeera’s investigative unit has spent five months delving into the corrupt sale of Egyptian gas to Israel. His report Egypt’s Lost Power to be broadcast on Monday night reveals that Egypt has lost a staggering amount of money -$11bn , with debts and legal liabilities of another $20bn – selling gas at rock bottom prices to Israel, Spain and Jordan. [Continue reading…]

Stories from an occupation: the Israelis who broke silence

Peter Beaumont reports: The young soldier stopped to listen to the man reading on the stage in Tel Aviv’s Habima Square, outside the tall façade of Charles Bronfman Auditorium. The reader was Yossi Sarid, a former education and environment minister. His text is the testimony of a soldier in the Israel Defence Forces, one of 350 soldiers, politicians, journalists and activists who on Friday – the anniversary of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land in 1967 – recited first-hand soldiers’ accounts for 10 hours straight in Habima Square, all of them collected by the Israeli NGO Breaking the Silence.

When one of the group’s researchers approached the soldier, they chatted politely out of earshot and then phone numbers were exchanged. Perhaps in the future this young man will give his own account to join the 950 testimonies collected by Breaking the Silence since it was founded 10 years ago.

In that decade, Breaking the Silence has collected a formidable oral history of Israeli soldiers’ highly critical assessments of the world of conflict and occupation. The stories may be specific to Israel and its occupation of the Palestinian territories but they have a wider meaning, providing an invaluable resource that describes not just the nature of Israel’s occupation but of how occupying soldiers behave more generally. They describe how abuses come from boredom; from the orders of ambitious officers keen to advance in their careers; or from the institutional demands of occupation itself, which desensitises and dehumanises as it creates a distance from the “other”. [Continue reading…]

A dangerous method: Syria, Sy Hersh, and the art of mass-crime revisionism

In the LA Review of Books, Muhammad Idrees Ahmad writes: On the day the London Review of Books published a widely circulated article by veteran journalist Seymour Hersh exonerating the Syrian regime for last year’s chemical attack, 118 Syrians, including 19 children, died in aerial bombing and artillery fire. Only the regime has planes and heavy ordnance.

Since last November, Aleppo has been targeted by helicopters dropping explosives-filled barrels from high altitudes. Between last November and the end of March, Human Rights Watch recorded 2,321 civilian deaths by this indiscriminate weapon. Only the regime has helicopters.

For many months after the chemical massacre, the targeted neighborhoods and the Yarmouk refugee camp were kept under a starvation siege. Aid agencies were denied entry. Only the regime controls access.

The regime’s ruthlessness has never been in doubt. Reports by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry, and myriad journalists and on-the-ground witnesses have repeatedly confirmed it. The regime has demonstrated the intent and capability to inflict mass violence. The repression is ongoing.

So when an attack occurred last August, employing a weapon that the regime was known to possess, using a delivery mechanism peculiar to its arsenal, in a place the regime was known to target, and against people the regime was known to loathe, it was not unreasonable to assume regime responsibility. This conclusion was corroborated by first responders, UN investigators, human rights organizations, and independent analysts.

When a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and a respectable literary publication undertake to challenge this consensus, one reasonably expects due diligence. The gravity of the matter demands that a high burden of proof be met. Sources would have to be vetted, claims corroborated, contrary evidence addressed.

But the editors didn’t do that. They gave precedence to storytelling over truth-telling. They disregarded available evidence and, based on the uncorroborated claims of a single unnamed source, absolved the perpetrator of a horrific atrocity, demonized his opponents, and slandered a foreign head of state. Worse, in using Hersh as click bait, they provided a smokescreen for new violations.

Five days after Hersh’s article went live, a military helicopter dropped a barrel bomb on Kafr Zita. This one carried toxic chlorine instead of the usual TNT. The regime, like Hersh, blamed the Islamist group Jabhat al-Nusra. But only the regime has an air force.

In a time of ongoing slaughter, to obfuscate the regime’s well-documented responsibility for a war crime does not just aid the regime today, it aids it tomorrow. As long as doubts remain about previous atrocities, there will be hesitancy to assign new blame. Accountability will be deferred.

Propaganda usually functions on one of two tracks: sometimes it builds support for a desired policy, sometimes it saps support for an undesired one. The former relies on persuasion, the latter on obfuscation. “Doubt is our product” is the assurance PR firms in the 1950s gave to a jittery tobacco industry facing accumulating scientific evidence linking cigarettes to cancer. Energy companies wishing to impede environmental legislation have since invested in the same strategy. This is also Hersh’s method. [Continue reading…]

Should citizens have a right to rebel?

Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez writes: Thailand’s Red-Shirt and Yellow-Shirt factions don’t agree on much, but they do have one thing in common: invoking Section 69 of the now-suspended Thai Constitution, which grants citizens a “right to peacefully resist any act committed to obtain powers to rule the country by means not in accordance with the modus operandi as provided in the Constitution.”

For years, during the slowly escalating crisis of protests and political polarization that eventually precipitated Thailand’s recent coup, leaders of ousted Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra’s ruling party warned against elite plots to subvert the democratic process—an outcome for which the “right to resist” served as a shield. Meanwhile, opponents of Thailand’s former government also invoked the provision, arguing that the real interruption of the constitutional order occurred with the hijacking of national institutions by a harsh and subversive majoritarian populism — one machinated from afar by the exiled billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra and his allies.

Thailand is not alone. In a study I co-authored with Tom Ginsburg of the University of Chicago and Emiliana Versteeg of the University of Virginia, we scoured the world’s constitutions looking for similar rights to resist. At present, 37 countries, representing roughly 20 percent of all nations, have such rights. The percentage is growing, having more than doubled since 1980.

For Americans, who are often by nature suspicious of government, this right may not sound like a bad idea. Granted, there is something paradoxical in the idea of a constitutional provision empowering individuals to resist, or in some cases openly rebel, against the very same authorities and institutions so meticulously established elsewhere in the same document. Nevertheless, it makes sense that the final say on matters of governance should lie with the people, and that such a clause might well serve as a valuable insurance policy in the future. [Continue reading…]

How Bowe Bergdahl went missing

In 2012, reporting for Rolling Stone in “America’s Last Prisoner of War,” Michael Hastings wrote: On June 27th [2009], [Bowe Bergdahl] sent what would be his final e-mail to his parents. It was a lengthy message documenting his complete disillusionment with the war effort. He opened it by addressing it simply to “mom, dad.”

“The future is too good to waste on lies,” Bowe wrote. “And life is way too short to care for the damnation of others, as well as to spend it helping fools with their ideas that are wrong. I have seen their ideas and I am ashamed to even be american. The horror of the self-righteous arrogance that they thrive in. It is all revolting.”

The e-mail went on to list a series of complaints: Three good sergeants, Bowe said, had been forced to move to another company, and “one of the biggest shit bags is being put in charge of the team.” His battalion commander was a “conceited old fool.” The military system itself was broken: “In the US army you are cut down for being honest… but if you are a conceited brown nosing shit bag you will be allowed to do what ever you want, and you will be handed your higher rank… The system is wrong. I am ashamed to be an american. And the title of US soldier is just the lie of fools.” The soldiers he actually admired were planning on leaving: “The US army is the biggest joke the world has to laugh at. It is the army of liars, backstabbers, fools, and bullies. The few good SGTs are getting out as soon as they can, and they are telling us privates to do the same.”

In the second-to-last paragraph of the e-mail, Bowe wrote about his broader disgust with America’s approach to the war – an effort, on the ground, that seemed to represent the exact opposite of the kind of concerted campaign to win the “hearts and minds” of average Afghans envisioned by counterinsurgency strategists. “I am sorry for everything here,” Bowe told his parents. “These people need help, yet what they get is the most conceited country in the world telling them that they are nothing and that they are stupid, that they have no idea how to live.” He then referred to what his parents believe may have been a formative, possibly traumatic event: seeing an Afghan child run over by an MRAP. “We don’t even care when we hear each other talk about running their children down in the dirt streets with our armored trucks… We make fun of them in front of their faces, and laugh at them for not understanding we are insulting them.”

Bowe concluded his e-mail with what, in another context, might read as a suicide note. “I am sorry for everything,” he wrote. “The horror that is america is disgusting.” Then he signed off with a final message to his mother and father. “There are a few more boxes coming to you guys,” he said, referring to his uniform and books, which he had already packed up and shipped off. “Feel free to open them, and use them.”

On June 27th, at 10:43 p.m., Bob Bergdahl responded to his son’s final message not long after he received it. His subject line was titled: OBEY YOUR CONSCIENCE!

“Dear Bowe,” he wrote. “In matters of life and death, and especially at war, it is never safe to ignore ones’ conscience. Ethics demands obedience to our conscience. It is best to also have a systematic oral defense of what our conscience demands. Stand with like minded men when possible.” He signed it simply “dad.”

Ordinary soldiers, especially raw recruits facing combat for the first time, respond to the horror of war in all sorts of ways. Some take their own lives: After years of seemingly endless war and repeat deployments, activeduty soldiers in the U.S. Army are currently committing suicide at a record rate, 25 percent higher than the civilian population. Other soldiers lash out with unauthorized acts of violence: the staff sergeant charged with murdering 17 Afghan civilians in their homes last March; the notorious “Kill Team” of U.S. soldiers who went on a shooting spree in 2010, murdering civilians for sport and taking parts of their corpses for trophies. Many come home permanently traumatized, unable to block out the nightmares.

Bowe Bergdahl had a different response. He decided to walk away. [Continue reading…]