Anne Applebaum writes: “How did he do it?” That’s the question I was asked more than once by European friends the day after Alabama’s Senate election: How did Doug Jones win? The question was not idle. In many ways, the electoral challenge Jones faced in Alabama was strikingly similar to the challenge facing European politicians of the center-left and even — or maybe especially — the center-right: How to defeat racist, xenophobic or homophobic candidates who are supported by a passionate, unified minority? Or, to put it differently: How to get the majority — which is often complacent rather than passionate, and divided rather than unified — to vote?

This was the same question asked after the victory of Emmanuel Macron in the French elections, and part of the answer, in both cases, was luck. Nobody predicted a Roy Moore sex scandal. Nobody predicted that the French political establishment would fold so quickly either. France’s previous, center-left president was so unpopular that he discredited his party; France’s center-right leader, François Fillon, was knocked out of the race by a scandal. Macron wound up as the leader of a new centrist coalition, the electoral arithmetic was in his favor, and he won.

But beyond luck, both Macron and Jones also tried to reach across some traditional lines, in part by appealing to traditional values. Macron, fighting a nationalist opponent in the second round of the elections, openly promoted patriotism. Instead of fear and anger, he projected optimism about France and its international role. He spoke of the opportunities globalization brought to France instead of focusing on the dangers, and he declared himself proud to be both French and a citizen of the world.

He wasn’t the only European to take this route: Alexander Van der Bellen, the former Green Party leader who is now president of Austria, used a similar kind of campaign to beat a nationalist opponent. Van der Bellen’s posters featured beautiful Alpine scenes, the Austrian flag and the slogan “Those who love their homeland do not divide it.”

In Alabama, Jones used remarkably similar language. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: anti-globalism

Trump’s ‘America first’ looks more and more like ‘America alone’

The Washington Post reports: On his third day in office, President Trump signed an executive memorandum withdrawing the United States from a 12-nation Asia-Pacific trade accord that had been painstakingly negotiated over a decade by two of his White House predecessors.

“Everyone knows what that means, right?” Trump asked rhetorically in the Oval Office. It meant, he said, that the country would start winning again in the face of unchecked globalization that had harmed ordinary Americans.

But on the 295th day of his presidency — during a trip to the region where the trade pact was most vital — a competing narrative emerged. Trump’s “America first” slogan has, in many ways, begun to translate into something more akin to “America alone.”

As the president’s motorcade wove up a mountain road Saturday to a regional summit in the Vietnamese city of Danang, news broke that the 11 nations that had once looked to U.S. leadership to seal the deal on the Trans-Pacific Partnership had moved on without the United States and announced a tentative agreement among themselves.

It marked a stunning turnabout that foreign-policy analysts warned could further erode U.S. standing at a time when China is embarked on a major economic expansion and further undermine global confidence in the United States’ ability to organize the world around its own liberal values. [Continue reading…]

The ‘Paradise Papers’ expose Trump’s fake populism

Ishaan Tharoor writes: President Trump entered the White House on a platform of populist rage. He channeled ire against the perceived perfidy and corruption of a shadowy world of cosmopolitan elites. He labeled his opponent Hillary Clinton a “globalist” — an establishment apparatchik supposedly motivated more by her ties to wealthy concerns elsewhere than by true patriotic sentiment.

“We will no longer surrender this country, or its people, to the false song of globalism,” Trump declared in a campaign speech in 2016, setting the stage for his “America First” agenda. The message was effective, winning over voters who felt they had lost out in an age defined by globalization, free trade and powerful multinational corporations.

Fast-forward a year, though, and it’s worth asking whether Trump — a scion of metropolitan privilege and a jet-setting tycoon who has long basked in his private world of gilded excess — ever seriously believed any of his own populist screeds. Little he has done since coming to power suggests a meaningful interest in uplifting the working class or addressing widening social inequities. Indeed, much of the legislation that he and his Republican allies are seeking to push through suggests the exact opposite. [Continue reading…]

China ascendant, U.S. floundering

Keith B. Richburg writes: Chinese President Xi Jinping could not have written a better script.

As China begins its 19th Communist Party Congress, with Xi set to be anointed to a second five-year term and cement his uncontested control, the Chinese leader is perfectly poised to look outward and exert global leadership.

He will be doing so precisely as the U.S. is turning inward, its politics appear increasingly dysfunctional, and a new administration, under its “America First” doctrine, is dramatically withdrawing from America’s traditional world leadership role.

Xi can largely thank Donald Trump for his good fortune. The American president began his presidency by withdrawing the U.S. from the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact. It was an accord largely of America’s making that was aimed at drawing the region closer to the U.S. economically, while potentially luring China to liberalize its economy as the price of entry. With the TPP now languishing, Beijing is pushing to conclude a rival trade pact, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or RCEP, by the end of this year.

Like the TPP, the rival pact will also comprise about 40% of the world economy. But the RCEP is dominated by China and India, and does not include any of the TPP’s agreements on labor rights, environmental protections or intellectual property rights. [Continue reading…]

Stephen Miller’s ascent powered by his fluency in the politics of grievance

The New York Times reports: Stephen Miller had their attention. That was reason enough to keep going.

Standing behind the microphone before a hostile amphitheater crowd, Mr. Miller — then a 16-year-old candidate for a student government post, now a 32-year-old senior policy adviser to President Trump — steered quickly into an unlikely campaign plank: ensuring that the janitorial staff was really earning its money.

“Am I the only one,” he asked, “who is sick and tired of being told to pick up my trash when we have plenty of janitors who are paid to do it for us?”

It appeared he was. Boos consumed the grounds of the left-leaning Santa Monica High School campus. Mr. Miller was forcibly escorted from the lectern, shouting inaudibly as he was tugged away.

But offstage, any anger seemed to fade instantly. Students were uncertain whether Mr. Miller had even meant the remarks sincerely. Those who encountered him afterward recalled a tranquillity, and a smile. If he had just lost the election — and he had, the math soon confirmed — he did not seem to feel like it.

“He just seemed really happy,” said Charles Gould, a classmate and friend at the time, “as if that’s how he planned it.”

In the years since, Mr. Miller has rocketed to the upper reaches of White House influence along a distinctly Trumpian arc — powered by a hyper-fluency in the politics of grievance, a gift for nationalist button-pushing after years on the Republican fringe and a long history of being underestimated by liberal forces who dismissed him as a sideshow since his youth.

Across his sun-kissed former home, the so-called People’s Republic of Santa Monica, they have come to regret this initial assessment. To the consternation of many former classmates and a bipartisan coalition of Washington lawmakers, Mr. Miller has become one of the nation’s most powerful shapers of domestic and even foreign policy. [Continue reading…]

The far right is reeling in professionals, hipsters, and soccer moms

Quartz reports: Following the political earthquakes of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, commentators tried to get a better understanding of who was leading this seismic change in politics. A picture quickly emerged: angry, working class (“left behind”) men were the driving force of right-wing populism. But a year of bruising elections in Europe has highlighted an uncomfortable truth—support for the far right is far more widespread then angry, old, white working class men.

Last Sunday (Sept 24), German voters put a far-right party into parliament for the first time since the Second World War. Right-wing nationalists Alternative for Germany (AFD) won 13% of the vote, easily overcoming the 5% threshold needed to enter the German Bundestag. A previous study (link in German) showed that AFD supporters come from different social classes, including workers, families with above-average incomes, and even academics. The study concluded that what was common among AFD voters was their dislike for Angela Merkel’s so-called open-door policy to refugees.

A snapshot of where AFD voters came from highlighted the party’s ability to win over voters from a wide array of political affiliations. Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (and its sister party the Christian Social Union) lost over one million voters to the AFD. But it wasn’t just right-wing voters who switched to the AFD; the center left Social Democrat lost over 500,000 (or 8.6%) of its 2013 voters to the AFD, the far left Left Party lost 420,000 (11%), and the Greens saw 50,000 defections (0.84%). Polling also showed that the AFD’s received the most votes among voters aged 33 to 44-year-old and that the party had done well with workers, and even managed to win over 10% of support from white-collar workers.

The AFD’s widespread support isn’t particularly surprising or unique. Far-right populism has always been dependent on a fragile coalition of voters—wealthy professionals, disaffected workers, and extremists—to break out of the margins and succeed. While white working class discontent is an important driving force for populism, so is anger from wealthy suburbanites and millennials. [Continue reading…]

The alt-left is real, and it’s helping fascists

Muhammad Idrees Ahmad writes: When Donald Trump used the term “alt-left” to deride the anti-fascists in Charlottesville last week, he was adopting a usage that has gained currency among far right ideologues on Fox News. It was Trump’s attempt to draw moral equivalence between the neo-Nazis and the protestors confronting them.

But the protestors in Charlottesville were traditional anti-fascists with a proud history and defined identity – there is nothing “alt” about them. If the label was being misapplied to them, maybe “alt-left” is nothing more than a right-wing media trope to smear progressive activists.Not quite. Before the right hijacked it, the “alt-left” label was used mainly by progressives to refer to a strain of leftism that sees liberalism rather than fascism as the main enemy. It is distinguished mainly by a reactionary contrarianism, a seething ressentiment, and a conspiracist worldview.

In its preoccupations it is closer to the right: More alarmed by Hillary Clinton winning the primary than by Donald Trump winning the presidency; more concerned with imagined “deep state” conspiracies than with actual Russian subversion of US democracy; eager to prevent a global war no one is contemplating but supportive of a US alliance with Russia for a new “war on terror”.

Like the right it disdains “globalists”, it sees internationalism as liberal frivolity, and its solidarity is confined to repressive regimes overseas.

Though these tendencies have always been a feature of the far left, they were turned into a powerful obstructive force after the last Democratic primary as the “never Hillary” fringe of Bernie Sanders supporters defected to the Green Party (in its worst incarnation under Jill Stein) or chose to sit out the election. Loath to admit mistake, the enablers of Trump now spend their time minimising what he has unleashed. [Continue reading…]

Pro-Trump/anti-Muslim/alt-right rallies in 36 states cancelled

Patch reports: ACT for America, the so-called “national security agency” known most recently for organizing anti-Sharia law rallies across the United States, has canceled 67 pro-Trump “America First” rallies in 36 states, citing “the recent violence in America and in Europe.” Instead the group said the 67 rallies planned for Sept. 9 will be replaced with an online “Day of ACTion.”

The group made the announcement in a statement given exclusively to Breitbart News, which it shared on its website and social media pages. While the group says the rallies were canceled “out of an abundance of caution,” the cancellation also comes at the heels of a “Free Speech” rally in Boston where thousands of counter-protesters drowned out a small group of rally-goers. [Continue reading…]

Right-wing militias are now actively supporting some state and local pro-Trump politicians

The Trace reports: Energized by Donald Trump’s coarsely confrontational nationalism, the armed right-wing fringe is doing more than stepping out of the shadows in 2017. Detachments of armed men in fatigues have become fixtures at liberal protests, forming the vanguard of what’s become known in some quarters as the “counter-resistance.”

Now, in a smattering of states with histories of right-wing extremism, chapters of groups like the Oath Keepers and Three Percenters may be emerging as even more direct political players, providing security for local pro-Trump politicians and Republican organizations. In one case, a Three Percenter was found to be employed on a state lawmaker’s staff.

When self-designated patriot groups first emerged during the early ‘90s, they identified as enemies of the “New World Order” heralded by George H.W. Bush, and tended to oppose the government, regardless of which party was in power. But experts say that the recent activity of some militia members could be evidence of a greater shift in political allegiances.

“You can’t be anti-government if your guy has the top job,” said Mark Pitcavage, who researches far-right extremism for the Anti-Defamation League.

With right-wing extremists who venerate the president looking for new enemies, some state and local politicians who are remaking partisanship in Trump’s image may see militias as a way to tighten their grip on power. The brash political style and “America First” agenda ushered into the Republican Party by Trump appeals to people in the militia movement, drawing them toward the political mainstream, said Amy Cooter, a sociologist at Vanderbilt University. Just as important, Cooter said, groups like the Three Percenters are eager for confrontation with anti-Trump liberals, who are themselves taking to the streets. “On the local level, some Republicans appear to be tapping into that agenda.” [Continue reading…]

The ugly history of Stephen Miller’s ‘cosmopolitan’ epithet

Jeff Greenfield writes: When TV news viewers saw Trump adviser Stephen Miller accuse Jim Acosta of harboring a “cosmopolitan bias” during Wednesday’s news conference, they might have wondered whether he was accusing the CNN White House reporter of an excessive fondness for the cocktail made famous on “Sex and the City.” It’s a term that’s seldom been heard in American political discourse. But to supporters of the Miller-Bannon worldview, it was a cause for celebration. Breitbart, where Steve Bannon reigned before becoming Trump’s chief political strategist, trumpeted Miller’s “evisceration” of Acosta and put the term in its headline. So did white nationalist Richard Spencer, who hailed Miller’s dust-up with Acosta as “a triumph.”

Why does it matter? Because it reflects a central premise of one key element of President Donald Trump’s constituency—a premise with a dark past and an unsettling present.

So what is a “cosmopolitan”? It’s a cousin to “elitist,” but with a more sinister undertone. It’s a way of branding people or movements that are unmoored to the traditions and beliefs of a nation, and identify more with like-minded people regardless of their nationality. (In this sense, the revolutionary pamphleteer Thomas Paine might have been an early American cosmopolitan, when he declared: “The world is my country; all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion.”). In the eyes of their foes, “cosmopolitans” tend to cluster in the universities, the arts and in urban centers, where familiarity with diversity makes for a high comfort level with “untraditional” ideas and lives.

For a nationalist, these are fighting words. Your country is your country; your fellow citizens are your brethren; and your country’s traditions—religious and otherwise— should be yours. A nation whose people—especially influential people—develop other ties undermine national strength, and must be repudiated.

One reason why “cosmopolitan” is an unnerving term is that it was the key to an attempt by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin to purge the culture of dissident voices. In a 1946 speech, he deplored works in which “the positive Soviet hero is derided and inferior before all things foreign and cosmopolitanism that we all fought against from the time of Lenin, characteristic of the political leftovers, is many times applauded.” It was part of a yearslong campaigned aimed at writers, theater critics, scientists and others who were connected with “bourgeois Western influences.” Not so incidentally, many of these “cosmopolitans” were Jewish, and official Soviet propaganda for a time devoted significant energy into “unmasking” the Jewish identities of writers who published under pseudonyms.

What makes this history relevant is that, all across Europe, nationalist political figures are still making the same kinds of arguments—usually but not always stripped of blatant anti-Semitism—to constrict the flow of ideas and the boundaries of free political expression. Russian President Vladimir Putin, for example, has more and more embraced this idea that unpatriotic forces threaten the nation. [Continue reading…]

Trump is ushering in a dark new conservatism

Timothy Snyder writes: In his committed mendacity, his nostalgia for the 1930s, and his acceptance of support from a foreign enemy of the United States, a Republican president has closed the door on conservatism and opened the way to a darker form of politics: a new right to replace an old one.

Conservatives were skeptical guardians of truth. The conservatism of the 18th century was a thoughtful response to revolutionaries who believed that human nature was a scientific problem. Edmund Burke answered that life is not only a matter of adaptations to the environment, but also of the knowledge we inherit from culture. Politics must respect what was and is as well as what might be.

The conservative idea of truth was a rich one.

Conservatives did not usually deny the world of science, but doubted that its findings exhausted all that could be known about humanity. During the terrible ideological battles of the 20th century, American conservatives urged common sense upon liberals and socialists tempted by revolution.

The contest between conservatives and the radical right has a history that is worth remembering. Conservatives qualified the Enlightenment of the 18th century by characterizing traditions as the deepest kind of fact. Fascists, by contrast, renounced the Enlightenment and offered willful fictions as the basis for a new form of politics. The mendacity-industrial complex of the Trump administration makes conservatism impossible, and opens the floodgates to the sort of drastic change that conservatives opposed. [Continue reading…]

Russia’s global anti-libertarian crusade

Cathy Young writes: One of the surreal twists of the past year in American politics has been the rapid realignment in attitudes toward Russia. Democrats, many of whom believe that Russian interference was key to Donald Trump’s unexpected victory last November, are now the ones sounding the alarm about the Russian threat. Meanwhile, quite a few Republicans—previously the keepers of the anti-Kremlin Cold War flame—have taken to praising President Vladimir Putin as a strong leader and Moscow as an ally against radical Islam. A CNN/ORC poll in late April found that 56 percent of Republicans see Russia as either “friendly” or “an ally,” up from 14 percent in 2014. Over the same period, Putin’s favorable rating from Republicans in the Economist/YouGov poll went from 10 percent to a startling 37 percent.

The dominant narrative in the U.S. foreign policy establishment and mainstream media casts Putin as the implacable enemy of the Western liberal order—an autocratic leader at home who wants to weaken democracy abroad, using information warfare and covert activities to subvert liberal values and to promote Russia-friendly politicians and movements around the world.

In this narrative, President Donald Trump is like the French nationalist Marine Le Pen, whose failed presidential campaign this year relied heavily on loans from Russian banks with Kremlin ties: a witting or unwitting instrument of subversion, useful to Putin either as an ideological ally or as an incompetent who will strengthen Russia’s hand by destabilizing American democracy.

At its extremes, the Russian subversion narrative relies on a great deal of conspiratorial thinking. It also far too easily absolves the Western political establishment of responsibility for its failures, from the defeat of European Union supporters in England’s Brexit vote to Hillary Clinton’s loss in last November’s election. Putin makes a convenient boogeyman.

Nonetheless, there is a real Russian effort to counter American—plus NATO and E.U.—influence by supporting authoritarian nationalist movements and groups, such as Le Pen’s National Front, Hungary’s quasi-fascist Jobbik Party, and Greece’s neo-Nazi Golden Dawn. Today’s Russia is no longer just a moderately authoritarian corrupt regime trying to maintain its regional influence. Cloaked in the mantle of religious and nationalist values, the Kremlin positions itself as a defender of tradition and sovereignty against the godless progressivism and the migrant hordes overtaking the West. It has a global propaganda machine and a network of political operatives dedicated to cultivating far-right and sometimes far-left groups in Europe and elsewhere.

Tom Palmer, vice president for international programs at the Atlas Network, has been actively involved in projects promoting liberty in ex-Communist countries since the late 1980s; he has taken to warning against a new “global anti-libertarianism.” Writing for the Cato Policy Report last December, Palmer noted that “Putin, the pioneer in the trend toward authoritarianism, has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into promoting anti-libertarian populism across Europe and through a sophisticated global media empire, including RT and Sputnik News, as well as a network of internet troll factories and numerous made-to-order websites.”

Slawomir Sierakowski of Warsaw’s Institute for Advanced Study and Emma Ashford of the Cato Institute have also warned about the rise of an “Illiberal International” in which Russia plays a key role.

Of course, for many libertarians, the post–Cold War international order that Putin seeks to undo is itself of dubious value. For one thing, that order is based on America’s role as GloboCop, which isn’t very compatible with small government. For another, it enforces its own “progressive” brand of soft authoritarianism, from over-regulation of markets to restrictions on “hate speech” and other undesirable expression. Yet for all the valid criticisms of the Western liberal establishment and its foreign and domestic policies, there is little doubt that the ascendancy of hardcore far-right or far-left authoritarianism would lead to a less freedom-friendly world. And there is little doubt that right now, Russia is a driving force in this ascendancy. [Continue reading…]

‘Our world has never been so divided,’ says French President Macron at close of G-20 summit at which U.S. isolated itself

The Washington Post reports: President Trump and other world leaders on Saturday emerged from two days of talks unable to resolve key differences on core issues such as climate change and globalization, slapping an exclamation point on a divisive summit that left other nations fearing for the future of global alliances in the Trump era.

The scale of disharmony was remarkable for the annual Group of 20 meeting of world economic powers, a venue better known for sleepy bromides about easy-to-agree-on issues. Even as negotiators made a good-faith effort to bargain toward consensus, European leaders said that a chasm has opened between the United States and the rest of the world.

“Our world has never been so divided,” French President Emmanuel Macron said as the talks broke up. “Centrifugal forces have never been so powerful. Our common goods have never been so threatened.”

The divisions were most bitter on climate change, where 19 leaders formed a unified front against Trump. But even in areas of nominal compromise, such as trade, top European leaders said they have little faith that an agreement forged today could hold tomorrow.

Macron said world leaders found common ground on terrorism but were otherwise split on numerous important topics. He also said there were rising concerns about “authoritarian regimes, and even within the Western world, there are real divisions and uncertainties that didn’t exist just a few short years ago.”

“I will not concede anything in the direction of those who are pushing against multilateralism,” Macron said, without directly referring to Trump. “We need better coordination, more coordination. We need those organizations that were created out of the Second World War. Otherwise, we will be moving back toward narrow-minded nationalism.” [Continue reading…]

The white nationalist roots of Donald Trump’s Warsaw speech

Jamelle Bouie writes: “The fundamental question of our time is whether the West has the will to survive,” said the president, before posing a series of questions: “Do we have the confidence in our values to defend them at any cost? Do we have enough respect for our citizens to protect our borders? Do we have the desire and the courage to preserve our civilization in the face of those who would subvert and destroy it?”

In the context of terrorism specifically, a deadly threat but not an existential one, this is overheated. But it’s clear Trump has something else in mind: immigration. He’s analogizing Muslim migration to a superpower-directed struggle for ideological conquest. It’s why he mentions “borders,” why he speaks of threats from “the South”—the origin point of Hispanic immigrants to the United States and Muslim refugees to Europe—and why he warns of internal danger.

This isn’t a casual turn. In these lines, you hear the influence of [Steve] Bannon and [Stephen] Miller. The repeated references to Western civilization, defined in cultural and religious terms, recall Bannon’s 2014 presentation to a Vatican conference, in which he praised the “forefathers” of the West for keeping “Islam out of the world.” Likewise, the prosaic warning that unnamed “forces” will sap the West of its will to defend itself recalls Bannon’s frequent references to the Camp of the Saints, an obscure French novel from 1973 that depicts a weak and tolerant Europe unable to defend itself from a flotilla of impoverished Indians depicted as grotesque savages and led by a man who eats human feces.

For as much as parts of Trump’s speech fit comfortably in a larger tradition of presidential rhetoric, these passages are clear allusions to ideas and ideologies with wide currency on the white nationalist right.

Defenders of the Warsaw speech call this reading “hysterical,” denying any ties between Trump’s rhetoric in Poland and white nationalism. But to deny this interpretation of the speech, one has to ignore the substance of Trump’s campaign, the beliefs of his key advisers, and the context of Poland itself and its anti-immigrant, ultranationalist leadership. One has to ignore the ties between Bannon, Miller, and actual white nationalists, and disregard the active circulation of those ideas within the administration. And one has to pretend that there isn’t a larger intellectual heritage that stretches back to the early 20th century, the peak of American nativism, when white supremacist thinkers like Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard penned works with language that wouldn’t feel out of place in Trump’s address. [Continue reading…]

Once dominant, the United States finds itself isolated at G-20

Trump was shunted to the far left and placed under Emmanuel Macron’s close supervision.

The New York Times reports: For years the United States was the dominant force and set the agenda at the annual gathering of the leaders of the world’s largest economies.

But on Friday, when President Trump met with 19 other leaders at the Group of 20 conference, he found the United States isolated on everything from trade to climate change, and faced with the prospect of the group’s issuing a statement on Saturday that lays bare how the United States stands alone.

Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, the host of the meeting, opened it by acknowledging the differences between the United States and the rest of the countries. While “compromise can only be found if we accommodate each other’s views,” she said, “we can also say, we differ.”

Ms. Merkel also pointed out that most of the countries supported the Paris accord on climate change, while Mr. Trump has abandoned it. “It will be very interesting to see how we formulate the communiqué tomorrow and make clear that, of course, there are different opinions in this area because the United States of America regrettably” wants to withdraw from the pact, she said.

Mr. Trump seemed to relish his isolation. For him, the critical moment of Friday was his long meeting with the Russian president, Vladimir V. Putin, which seemed to mark the reset in relations that Mr. Trump has been desiring for some time. It also provided Mr. Putin the respect and importance he has long demanded as a global partner to Washington.

Where previous American leaders saw their power as a benevolent force, and were intent on spreading prosperity through open markets and multilateral cooperation, Mr. Trump has portrayed himself as a nationalist, a unilateralist and a protectionist, eager to save American jobs.

What recent events have underscored, though — and especially at the G-20 — is that no nation is today large or powerful enough to impose rules on everyone else. In advancing his views, Mr. Trump has alienated allies and made the United States seem like its own private island. [Continue reading…]

What happens when the whole world becomes selfish

David Ignatius writes: When the leader of the global system proclaims that he won’t be bound by foreign restraints, the spirit becomes infectious. Call the global zeitgeist what you will: The new realism. Eyes on the prize. Winning isn’t the most important thing, it’s the only thing.

Middle East leaders have been notably more aggressive in asserting their own versions of national interest. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates defied pleas from Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to stop escalating their blockade against Qatar for allegedly supporting extremism. Their argument was simple self-interest: If Qatar wants to ally with the Gulf Arabs, then it must accept our rules. Otherwise, Qatar is out.

For the leaders of Iraqi Kurdistan, the issue has been whether to wait on their dream of independence. They decided to go ahead with their referendum, despite worries among top U.S. officials that it could upset American efforts to hold Iraq together and thereby destabilize the region. The implicit Kurdish answer: That’s not our problem. We need to do what’s right for our people.

Trump has at least been consistent. His aides cite a benchmark speech he made April 27, 2016, at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, in which he offered an early systematic “America first” pitch. He argued that the country had been blundering around the world with half-baked, do-gooder schemes “since the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union.”

Trump explained: “It all began with a dangerous idea that we could make Western democracies out of countries that had no experience or interest in becoming a Western democracy. We tore up what institutions they had and then were surprised at what we unleashed.”

What’s interesting is that this same basic critique has been made, almost word for word, by Russian President Vladimir Putin. That’s not a conspiracy-minded argument that Trump is Putin’s man, but simply an observation that our president embraces the same raw cynicism about values-based foreign policy as does the leader of Russia. [Continue reading…]

The French presidency goes to Macron. But it’s only a reprieve

Timothy Garton Ash writes: Like someone who has narrowly escaped a heart attack, Europe can raise a glass and give thanks for the victory of Emmanuel Macron. But the glass is less than half full, and if Europe doesn’t change its ways it will only have postponed the fateful day.

The next president of France will be a brilliant product of that country’s elite, with a clear understanding of France’s deep structural problems, some good ideas about how to tackle them, a strong policy team, and a deep commitment to the European Union. When a centrist pro-European government has been formed in Berlin after the German election this autumn, there is a chance for these two nations to lead a consolidatory reform of the EU.

Savour those drops of champagne while you can, because you’ve already drained the glass. Now for the sobering triple espresso of reality. First shot: more than a third of those who turned out in the second round voted for Marine Le Pen (at the time of writing we don’t have the final figures). What times are these when we celebrate such a result?

Thanks to France’s superior electoral system and strong republican tradition, the political outcome is better than the victories of Donald Trump and Brexit, but the underlying electoral reality is in some ways worse. Trump came from the world of buccaneer capitalism, not from a long-established party of the far right; and most of the 52% who voted for Brexit were not voting for Nigel Farage. After Le Pen’s disgusting, mendacious, jeering performance in last Wednesday’s television debate, no one could have any doubt who they were voting for. She makes Farage look almost reasonable. [Continue reading…]

The French elections showed the strength of the European far-right — and its limits

Zack Beauchamp writes: To understand what France’s election means, and what it tells us about the rise of far-right movements around Europe, you need to understand two fundamental truths about the results.

The first is that it’s a historic victory for the far-right Marine Le Pen and her Front National party. Le Pen was one of two candidates who qualified for the second round, soundly beating the standard-bearers both of France’s traditional establishment parties — the center-right Republicans and center-left Socialists. The once-reviled Front has clearly entered the mainstream of French politics.

At the same time, the election seemed to demonstrate the very clear limits of Le Pen’s popularity — and, potentially, European far-right politics more broadly.

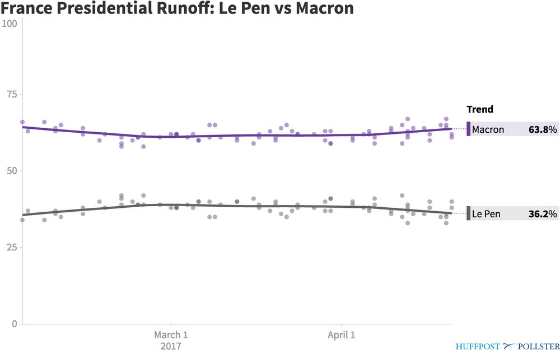

Le Pen came in second in Sunday’s election, with 21.7 percent of the vote. The plurality winner, upstart centrist Emmanuel Macron, won with 23.9 percent. He’s her polar opposite in virtually every respect. She wants to restrict immigration to France and pull France out of the EU; he supports keeping the borders open and proudly waved the EU flag at his final campaign rally. And when these two face each other one-on-one in a runoff in two weeks, he’s very likely to win — every poll that’s been taken so far has him up by massive margins:

The tolerant center, in France, appears likely to hold.What we’re seeing in France mirrors what’s happening in much of Europe. After the twin shocks of Brexit and Trump, the far-right has seen a series of setbacks. From elections in Austria and the Netherlands to polls in all-important Germany, the far-right is performing far less well than many have expected.

What these numbers suggest is that the far-right has a political ceiling: That while its supporters may be hard-core, the majority of Europeans still recoil from its vision — at least for now. [Continue reading…]