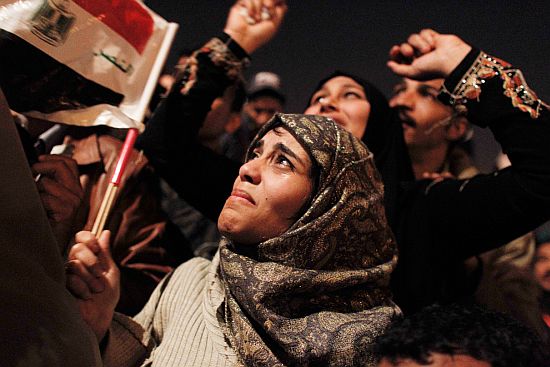

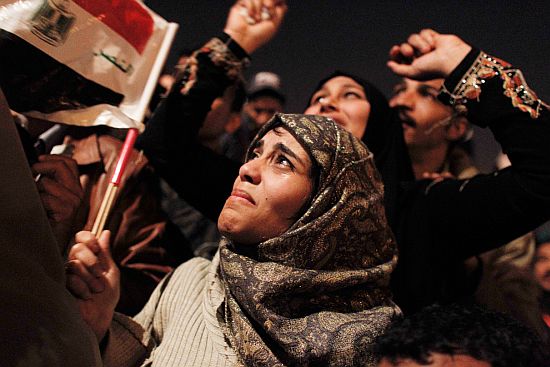

An Egyptian woman cries as she celebrates the news of the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak.

Some think the Middle East isn’t ready for democracy — in truth it’s the West that isn’t ready.

Nicholas Kristof duly notes:

Egyptians triumphed over their police state without Western help or even moral support. During rigged parliamentary elections, the West barely raised an eyebrow. And when the protests began at Tahrir Square, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said that the Mubarak government was “stable” and “looking for ways to respond to the legitimate needs and interests of the Egyptian people.”

Commentators have repeatedly referred to the Obama administration playing catch-up during the Egyptian revolution, yet its seeming inability to track fast-changing events was merely an expression of its unwillingness to embrace the direction those events were heading.

Immediately after Hosni Mubarak resigned, Jake Tapper from ABC News tweeted that he couldn’t find anyone in the administration who thought that whatever comes next would be better for U.S. interests than Mubarak had been.

The dictator’s departure is not being celebrated in Washington. The leaders of the free world have a singular lack of enthusiasm for freedom.

The administration has not merely repeatedly stumbled, but has functioned as a dead weight, attempting to slow the pace of what may become the most significant transformation in world order since the birth of Western colonial power.

America’s friends in Israel have been equally unenthusiastic about the turn of events. After Mubarak’s defiant speech on Thursday night when he insisted he would sit out his term as president, “Israel breathed a sigh of relief,” according to Israeli commentator, Alex Fishman. The respite must have felt dreadfully brief.

But if Americans want to grasp the significance of the Egyptian revolution, they need look no further than this country’s much bloodier assertion of people power: the American revolution.

For the first time in Egypt’s history, the Egyptian people have made a declaration of sovereignty and claimed their right of self-governance. Is that not something that every person on the planet who cherishes life and liberty can joyfully celebrate?

As Western leaders now line up, having no choice but to express their support for the revolution, while sagely offering guidance and assistance in managing an “orderly transition” to a democratic system, they do so with a palpable ambivalence.

People power is in jeopardy of sweeping the Middle East and undoing the carefully constructed “stability” through which for most of the last century the West has managed the control of its most vital resource: oil.

Worse for the United States, the Egyptian revolution now undermines the US government’s ability to sustain an unswerving loyalty to the preeminence of Israel’s security interests.

A democratic Egyptian government will not have the autocratic latitude that until now enabled Mubarak’s complicity in the siege of Gaza or his willingness to participate in the charade of a peace process going nowhere.

Stepping back from the most obvious regional implications of what is now unfolding, there is a more far-reaching dimension.

When in 1990 President George HW Bush used the phrase “new world order”, his words had an ominous ring both because they implied that this would be an American-defined order but also — on the brink of the first Gulf War — a militarily-imposed order. The new order was synonymous with the dubious claim that the collapse of the Soviet Union represented an American “victory” in the Cold War.

A new world order worthy of the name, however, should represent something much more significant than the strategic reapportioning of power on a geopolitical level. It should involve the reapportioning of power through which global affairs become the people’s affairs. It should mean that international relations can no longer be conducted within the confines of intrinsically undemocratic arenas where ordinary people have no voice.

The people-power unleashed in Egypt has the potential to serve as a democratizing force that not only threatens autocratic leaders in the Middle East but also technocratic and nominally democratic leaders in the West — those whose complacent style of governance has depended on the political passivity of the populations they nominally serve while providing ready access for corporate interests to exercise their undemocratic influence.

The West, far from representing a model of democracy ripe for export has instead long been mired in a post-democratic phase where the foundational concept of demos, the people, has withered.

Individual wealth has supplanted the need for social solidarity as citizenship has been substituted by consumerism. Our material self-sufficiency has robbed us of the experience of mutual reliance and worn thin the fabric of society.

In a new world order, a new democracy might spread not just further east but also further west.

There is also a bittersweet note in this moment.

The Western exporters of democracy delivered the war in Iraq and yet as we witness events unfold in Egypt, it’s hard not to wonder what might have been possible had the people of Iraq, without Western help or hindrance, been allowed the same opportunity to claim their own freedom.

Many American academics and pundits from thinktankland should study the way Slavoj Žižek expresses himself. Passionate, emphatic, uninhibited, eccentric, and humorous — above all, a man who knows what it means to speak your mind. This is a display that shows that deep analysis does not need the protection of cover-your-ass-caveats or manicured sobriety. It can be an act of genuine self-expression.

Many American academics and pundits from thinktankland should study the way Slavoj Žižek expresses himself. Passionate, emphatic, uninhibited, eccentric, and humorous — above all, a man who knows what it means to speak your mind. This is a display that shows that deep analysis does not need the protection of cover-your-ass-caveats or manicured sobriety. It can be an act of genuine self-expression.