There was an age when those afraid of dying knew they should, if they could, stay away from war. They could instead, if so inclined, read about war and fantasize about battlefield heroics from the comfort of an armchair. Nowadays, America’s newest class of warriors enjoy the same comfort with as little risk.

The drone is our latest wonder weapon and a bragging point in a set of wars where there has been little enough to brag about.

CIA director Leon Panetta has, for instance, called the Agency’s drones flying over Pakistan “the only game in town” when it comes to destroying al-Qaeda; a typically anonymous U.S. official in a Washington Post report claims of drone missile attacks, “We’re talking about precision unsurpassed in the history of warfare”; or as Gordon Johnson of the Pentagon’s Joint Forces Command told author Peter Singer, speaking of the glories of drones: “They don’t get hungry. They are not afraid. They don’t forget their orders. They don’t care if the guy next to them has been shot. Will they do a better job than humans? Yes.”

Seven thousand of them, the vast majority surveillance varieties, are reportedly already being operated by the military, and that’s before swarms of “mini-drones” come on line. Our American world is being redefined accordingly.

In February, Greg Jaffe of the Washington Post caught something of this process when he spent time with Colonel Eric Mathewson, perhaps the most experienced Air Force officer in drone operations and on the verge of retirement. Mathewson, reported Jaffe, was trying to come up with an appropriately new definition of battlefield “valor” — a necessity for most combat award citations — to fit our latest corps of pilots at their video consoles. “Valor to me is not risking your life,” the colonel told the reporter. “Valor is doing what is right. Valor is about your motivations and the ends that you seek. It is doing what is right for the right reasons. That to me is valor.”

There is a simple calculus upon which American warfare depends: the fewer Americans get killed, the longer the war can continue.

Maimed Americans don’t count. As for dead or maimed non-Americans, they are a variable part of the calculus, problematic or not depending on the circumstances.

The Pentagon’s love of the drone is Washington’s dread of the dead — let’s not pretend that valor has any place in this equation.

When through the press of a button a soldier in an air-conditioned office rains down death and destruction thousands of miles away, whatever military virtues he might possess, there’s no reason to assume they include bravery. Indeed, the risk-free killing of remote warfare is really the most cowardly form of combat, far removed as it is from battlefields that demand courage because the killers risk being killed.

In Shakespeare’s Henry V, as the Battle of Agincourt is about to commence, the king addresses his men — “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers” — heavily outnumbered by the French and facing the risk of imminent slaughter.

Henry — a king who fights with his men and doesn’t simply issue commands — declares:

… he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse;

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

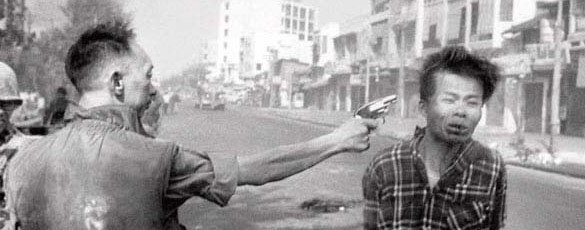

To the extent that there is a noble dimension to warfare it is this: that those willing to kill are also willing to die. Those taking the lives of others do so knowing that just as easily they could lose their own.

The technological advance of war has broken this equation and broken it so thoroughly that not only does the new class of drone-armed killers face no risk of being killed; they may not even lose any sleep.

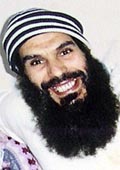

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target.

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target. In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of

In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of

Henry — a king who fights with his men and doesn’t simply issue commands — declares:

Henry — a king who fights with his men and doesn’t simply issue commands — declares: Mr Tal did not exactly conceal his prior affiliations when he appeared on Fox News during the 2006 Lebanon war. He opined then that “this is a war that Israel cannot afford to lose”.

Mr Tal did not exactly conceal his prior affiliations when he appeared on Fox News during the 2006 Lebanon war. He opined then that “this is a war that Israel cannot afford to lose”.