The Guardian reports: If Joseph and Mary were making their way to Bethlehem today, the Christmas story would be a little different, says Father Ibrahim Shomali, a parish priest in the town. The couple would struggle to get into the city, let alone find a hotel room.

“If Jesus were to come this year, Bethlehem would be closed,” says the priest of Bethlehem’s Beit Jala parish. “He would either have to be born at a checkpoint or at the separation wall. Mary and Joseph would have needed Israeli permission – or to have been tourists.

“This really is the big problem for Palestinians in Bethlehem: what will happen when they close us off completely?”

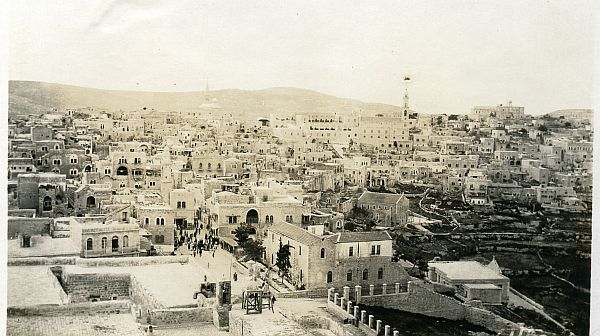

Bethlehem is the heart of Christian Palestine and it swells with pride every Christmas. Manger Square is transformed into a grotto of lights and stalls crowned by a towering Christmas tree. Strings of illuminated angels, stars and bells festoon the streets. But just a few minutes’ drive to the north, the festive atmosphere stops abruptly.

A strip of Israeli settlements built on 18 sq km of what was once northern Bethlehem threatens to cut the city off from its historic twin, Jerusalem. To the Israeli authorities, these have been neighbourhoods of Jerusalem since 1967. One of the settlements, Har Homa, is built on land where angels are said to have announced the birth of Christ to local shepherds. A narrow corridor of land between Har Homa and another settlement, Gilo, still connects Bethlehem to Jerusalem but the construction of Givat Hamatos, a new settlement announced in October, will fill this in a matter of years.

The European Union and United Nations routinely denounce Israel’s unilateral settlement expansion but in October, EU high commissioner Baroness Catherine Ashton warned the construction of Givat Hamatos was “of particular concern as [it] would cut the geographic contiguity between Jerusalem and Bethlehem”.

European concern is not slowing Israel’s progress. Last week, 500 new units were approved for Har Homa and a further 348 in Betar Illit, on Bethlehem’s western boundary. Earlier this month, an additional 267 units were sanctioned for settlements running up to the edge of the city’s southern suburbs, where the Ministry of Defence also gave settlers permission to start a farm on Palestinian land. This is in addition to the 6,782 new apartments already slated for Har Homa, Gilo and Givat Hamatos.

In the short term, the closure won’t make a big difference to everyday life in Bethlehem: the separation wall already prevents Palestinians from entering Jerusalem from the town without an Israeli permit.

But this ring of settlements will permanently change the geography of the biblical landscape: if a peace agreement razes the separation wall, the two cities will remain divided.

Israeli activist Hargit Ofram, director of Peace Now, reads a clear political intention in Israel’s plans: “These efforts are being made to prevent a possible two-state solution because in order for that to work, you would need a viable Palestinian state with its capital in East Jerusalem.

“If that capital is going to be surrounded by settlements, Israel would have to remove them. The more Israel is building, the higher the price of a Palestinian state is becoming.”

A year ago, Mayor Victor Batarseh described the impact of the occupation on the Bethlehem and Palestinian Christians who wish to visit the town to celebrate Christmas.