Micah White writes: I have sometimes been approached by persons that I suspected were either agents or assets of intelligence agencies during the 20 years that I have been a social activist. The tempo of these disconcerting encounters increased when I abruptly relocated to a remote town on the Oregon coast after the defeat of Occupy Wall Street, a movement I helped lead. My physical inaccessibility seemed to provoke a kind of desperation among these shadowy forces.

There was the man purporting to be an internet repair technician who arrived unsolicited at our rural home and then tinkered with our modem. Something felt odd and I was not surprised when CNN later reported that posing as internet repairmen is a known tactic of the FBI.

I’ve had other suspicious encounters. A couple seeking advice on starting a spiritual activist community, for example, but whose story made little sense. And a former Occupy activist who moved to my town to, I felt, undermine my activism and gather information about me.

Those few friends that I confided in dismissed my suspicions as mild paranoia. And perhaps it was. I stopped talking about it and instead became highly selective about the people I met, emails I responded to and invitations I accepted.

I hinted at the situation by adding a section to my book, The End of Protest, warning activists to beware of frontgroups. And, above all, I learned to trust my intuition – if someone gave me a tingly sense then I stayed away. That is why I almost ignored the interview request from Yan Big Davis. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Occupy Wall Street

Occupy activist Cecily McMillan sentenced to three months in prison

The Guardian reports: An Occupy Wall Street activist has been sentenced to three months in prison for assaulting a police officer as he led her out of a protest.

Cecily McMillan, who had been facing a maximum sentence of seven years, was told on Monday morning by Judge Ronald Zweibel that she “must take responsibility for her conduct”.

“A civilised society must not allow an assault to be committed under the guise of civil disobedience,” said Zweibel at Manhattan criminal court. However, he added: “The court finds that a lengthy sentence would not serve the interests of justice in this case.”

McMillan, 25, received a three-month sentence to be followed by community service and five years of probation. Having been remanded at Riker’s Island jail for the past two weeks, she will receive credit for time served. [Continue reading…]

Cecily McMillan’s Occupy trial is a huge test of U.S. civil liberties. Will they survive?

Chase Madar writes: The US constitution’s Bill of Rights is envied by much of the English-speaking world, even by people otherwise not enthralled by The American Way Of Life. Its fundamental liberties – freedom of assembly, freedom of the press, freedom from warrantless search – are a mighty bulwark against overweening state power, to be sure.

But what are these rights actually worth in the United States these days?

Ask Cecily McMillan, a 25-year-old student and activist who was arrested two years ago during an Occupy Wall Street demonstration in Manhattan. Seized by police, she was beaten black and blue on her ribs and arms until she went into a seizure. When she felt her right breast grabbed from behind, McMillan instinctively threw an elbow, catching a cop under the eye, and that is why she is being prosecuted for assaulting a police officer, a class D felony with a possible seven-year prison term. Her trial began this week.

McMillan is one of over 700 protestors arrested in the course of Occupy Wall Street’s mass mobilization, which began with hopes of radical change and ended in an orgy of police misconduct. According to a scrupulously detailed report (pdf) issued by the NYU School of Law and Fordham Law School, the NYPD routinely wielded excessive force with batons, pepper spray, scooters and horses to crush the nascent movement. And then there were the arrests, often arbitrary, gratuitous and illegal, with most charges later dismissed. McMillan’s is the last Occupy case to be tried, and how the court rules will provide a clear window into whether public assembly stays a basic right or becomes a criminal activity. [Continue reading…]

NYPD ‘consistently violated basic rights’ during Occupy protests – study

The Guardian reports: The first systematic look at the New York police department’s response to Occupy Wall Street protests paints a damning picture of an out-of-control and aggressive organization that routinely acted beyond its powers.

In a report that followed an eight-month study (pdf), researchers at the law schools of NYU and Fordham accuse the NYPD of deploying unnecessarily aggressive force, obstructing press freedoms and making arbitrary and baseless arrests.

The study, published on Wednesday, found evidence that police made violent late-night raids on peaceful encampments, obstructed independent legal monitors and was opaque about its policies.

The NYPD report is the first of a series to look at how police authorities in five US cities, including Oakland and Boston, have treated the Occupy movement since it began in September 2011. The research concludes that there now is a systematic effort by authorities to suppress protests, even when these are lawful and pose no threat to the public.

Sarah Knuckey, a professor of law at NYU, said: “All the case studies we collected show the police are violating basic rights consistently, and the level of impunity is shocking”.

To be launched over the coming months, the reports are being done under the Protest and Assembly Rights Project, a national consortium of law school clinics addressing America’s response to Occupy Wall Street.

The NYPD appears to be the worst offender, in large part because it has made little attempt – unlike Oakland, for example – to reassess its practices or open itself up to dialogue or review. [Continue reading…]

Accusations that NYPD tried to spy on Wall St. protesters

The New York Times reports: On Monday, the New York Police Department sent its warrant squads after an unusual set of suspects: people who had old warrants for the lowliest of violations, misconduct too minor, usually, to draw the attention of those squads.

But those who were questioned by the warrant squads said the officers had an ulterior motive: gathering intelligence for the Occupy Wall Street protests scheduled for May 1, or May Day. One person said he was interviewed about his plans for May Day. A second person said the police examined political fliers in his apartment, and then arrested him on a warrant for a 2007 open-container-of-alcohol violation.

Officials have yet to respond to questions about the tactics, but one police official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to reporters about police policy, said the strategy appeared to be an extension of a policy used at events where crowd control could be an issue. Before certain parades that have been marred by shootings, for example, the warrant squads have tracked down gang members who live nearby to execute outstanding warrants, no matter how minor, the official said.

But the department’s use of this tactic as part of its strategy for policing the Occupy Wall Street movement raises new questions about the surveillance efforts by the Police Department, which faces restrictions in monitoring political groups.

Zachary Dempster, 31, said he was wakened at 6:15 a.m. Monday by plainclothes police officers who entered his apartment on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn and herded him and two roommates into the living room. There, Mr. Dempster said, the police announced they were there that morning to serve an open-container warrant on one of the roommates, Joseph Ryan, a musician who goes by the name Joe Crow Ryan. But then one of the officers led Mr. Dempster back to his room for questioning.

“The officer said, ‘What are you doing tomorrow?’ ” Mr. Dempster recalled. “Do you have plans for May Day?”

“I said, ‘I’m not going to talk to you without my lawyer present,’ ” Mr. Dempster said, adding, “It didn’t seem right.” [Continue reading…]

An oral history of Occupy Wall Street

Vanity Fair: On September 17, several hundred people marched to an empty square in Lower Manhattan—a place so dull that the bankers and construction workers in the neighborhood barely knew it was there—and camped out on the bare concrete. They would be joined, over the next two months, by thousands of supporters, who erected tents, built makeshift institutions—a field hospital, a library, a department of sanitation, a free-cigarette dispensary—and did a fair amount of drumming.

It was easy to infer from the signs protesters carried what the grievances that gave rise to Occupy Wall Street were: an ever widening gap between rich and poor; a perceived failure by President Obama to hold the financial industry accountable for the crisis of 2008; and a sense that money had taken over politics.

The amazing thing about the Occupy Wall Street movement is not that it started—America was full of fed-up people at the end of 2011—but that it worked. With a vague agenda, a nonexistent leadership structure (many of the protesters were anarchists and didn’t believe in leaders at all), and a minuscule budget (as of December, they’d raised roughly $650,000—one-eighth of Tim Pawlenty’s presidential campaign haul), the occupiers in Zuccotti Park nevertheless inspired similar protests in hundreds of cities around the country and the world. What they created was, depending on whom you asked, either the most important protest movement since 1968 or an aimless, unwashed, leftist version of the Tea Party.

Occupy Wall Street quickly attracted intellectual celebrities—and, eventually, actual celebrities—but its founders were an unlikely assortment of stifled activists, part-time provocateurs, and people who simply had no place else to turn. There was Kalle Lasn, who ran an obscure Vancouver-based magazine called Adbusters with just 10 employees and an anti-consumerist agenda. Another key organizer, Vlad Teichberg, was a 39-year-old former derivatives trader who spent his weekends and evenings producing activist video art. David Graeber, an anthropologist at the University of London, quickly emerged as the movement’s intellectual force. If he was known at all, it was not for his anarchist theories or for his research into the nature of debt, but for being let go by Yale in 2005—in part, he believes, on account of his political leanings.

It is unclear whether the impact of Occupy Wall Street will be lasting or brief. But the story of how these unlikely organizers—and the activists, students, and homeless people who joined them—managed to seize control of the national conversation is remarkable, miraculous even. This is how it happened.

The rise and fall of Zuccotti Park — and the future of the movement it birthed

Christopher Ketcham writes: In the month before the destruction of the encampment in Zuccotti Park, I got in the habit of biking across the Brooklyn Bridge each night to talk with the Wall Street Occupiers and wander among the tents. There was always work to behold—bigger tents going up, new volunteers welcomed, the kitchen doling out free food, the media groups live-streaming, dishes being done, cops being teased—and always conversation to be had and heard.

The protesters liked to work, but they loved to talk, and mostly what they talked about was how to organize to destroy the power of money in America. They were pissed off about it—pissed off at the corporations, the banks, the financiers, the corrupt legislators, the corrupt presidents, the corrupt everything. “It doesn’t matter which party is in power,” Jeff Smith, a 41-year-old former media consultant, told me. “The banks and the corporations own them both.” And President Barack Obama? “He is worse than a corporate whore like Bill Clinton,” Smith said. “He’s like a Trojan Horse for the right-wing agenda. Obama mesmerizes his base of true believers with the skill of a televangelist and then turns around and sells them out in backroom deals with the plutocrats he seems to worship. It’s hard not to realize that his incompetence and/or duplicity is a driving factor behind Occupy Wall Street.”

Such was the talk. When they spoke honestly, the Occupiers admitted that they had no idea what to do about the total corruption of everything—except what they were doing in Zuccotti Park.

So they would occupy the space, hold the ground, and fill it with unwashed humanity, which is the kind of thing that’s not supposed to happen in Manhattan’s Financial District. They came in all races, all ages. There were schoolteachers, professors, ex-servicemen, sculptors, painters, dancers, musicians, writers, at least one retired male stripper, at least one Native American, many college students, some high-schoolers, and the homeless. They carved a community out of the park, a society in miniature, with its own rules and government and infrastructure—a library, kitchen, clinic, a newspaper called The Occupied Wall Street Journal, and even a tobacconist. They marched on Wall Street each day, made trouble, made noise, got arrested, met in a daily “general assembly” and in “working groups,” planned for the winter, and organized, not least, to make more trouble.

“This is not a protest,” one of their signs said. “This is an affirmation of the vitality and idealism erupting from underneath the AMERICAN NIGHTMARE.” The library grew ever larger—it soon had 5,000 titles, the only all-night library in the city—and the signs proliferated. “Jobs, Justice, Education,” they said. And: “End Student Debt.” And: “Reinstate Glass-Steagall; Make Corporate Lobbying Illegal.” The signs said that Wall Street was “the enemy of humanity.” They said, “We need only overthrow the investors—not the government.” More tents sprung up through October and November, the campers packing in by the hundreds, until little space was left. The expanding movement was forced to find nearby offices, at 50 Broadway, where it could now claim to have a bureaucracy. [Continue reading…]

Occupy 2012

John Heilemann writes: In just two months of existence, OWS had scored plenty of victories: spreading from New York to more than 900 cities worldwide; introducing to the vernacular a potent catchphrase, “We are the 99 percent”; injecting into the national conversation the topic of income inequality. But OWS had also suffered setbacks. The less savory aspects of the occupations had provided the right with fuel for feral slander (Drudge: “Death, Disease Plague ‘Occupy’ Protests”) and casual caricature. Even among some protesters, there was a sense that stagnation had set in. Then came the Zuccotti clampdown—and the popular perception that it meant the end of OWS.

It’s perfectly possible that this perception will be borne out, that the raucous events of November 17 were the last gasps of a rigor-mortizing rebellion. But no one seriously involved in OWS buys a word of it. What they believe instead is that, after a brief period of retrenchment, the protests will be back even bigger and with a vengeance in the spring—when, with the unfurling of the presidential election, the whole world will be watching. Among Occupy’s organizers, there is fervid talk about occupying both the Democratic and Republican conventions. About occupying the National Mall in Washington, D.C. About, in effect, transforming 2012 into 1968 redux.

The people plotting these maneuvers are the leaders of OWS. Now, you may have heard that Occupy is a leaderless uprising. Its participants, and even the leaders themselves, are at pains to make this claim. But having spent the past month immersed in their world, I can report that a cadre of prime movers—strategists, tacticians, and logisticians; media gurus, technologists, and grand theorists—has emerged as essential to guiding OWS. For some, Occupy is an extension of years of activism; for others, their first insurrectionist rodeo. But they are now united by a single purpose: turning OWS from a brief shining moment into a bona fide movement.

That none of these people has yet become the face of OWS—its Tom Hayden or Mark Rudd, its Stokely Carmichael or H. Rap Brown—owes something to its newness. But it is also due to the way that Occupy operates. Since the sixties, starting with the backlash within the New Left against those same celebrities, the political counterculture has been ruled by loosey-goosey, bottom-up organizational precepts: horizontal and decentralized structures, an antipathy to hierarchy, a fetish for consensus. And this is true in spades of OWS. In such an environment, formal claims to leadership are invariably and forcefully rejected, leaving the processes for accomplishing anything in a state of near chaos, while at the same time opening the door to (indeed compelling) ad hoc reins-taking by those with the force of personality to gain ratification for their ideas about how to proceed. “In reality,” says Yotam Marom, one of the key OWS organizers, “movements like this are most conducive to being led by people already most conditioned to lead.”

And so in coffee shops and borrowed conference rooms around the city, far from the sound and fury in the park and on the streets, the prime movers have been doing just that—meeting, planning, talking (and talking) about the future of OWS. The debates between them have been fierce. Tensions have been laid bare, factions fomented, and ideological cleavages exposed—all of it a familiar recapitulation of the growing pains experienced by protesters of the past, from those in favor of civil rights and against the Vietnam War in the sixties to those fighting for workers’ rights in the thirties.

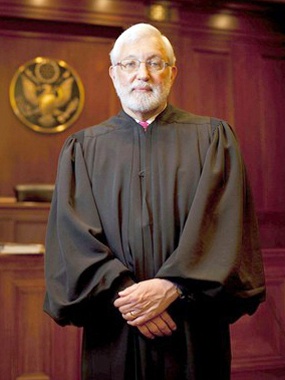

The federal judge who kicked the SEC out of bed with the banks

Matt Taibbi writes: In one of the more severe judicial ass-whippings you’ll ever see, federal Judge Jed Rakoff rejected a slap-on-the-wrist fraud settlement the SEC had cooked up for Citigroup.

I wrote about this story a few weeks back when Rakoff sent signals that he was unhappy with the SEC’s dirty deal with Citi, but yesterday he took this story several steps further.

Rakoff’s 15-page final ruling read like a political document, serving not just as a rejection of this one deal but as a broad and unequivocal indictment of the regulatory system as a whole. He particularly targeted the SEC’s longstanding practice of greenlighting relatively minor fines and financial settlements alongside de facto waivers of civil liability for the guilty – banks commit fraud and pay small fines, but in the end the SEC allows them to walk away without admitting to criminal wrongdoing.

This practice is a legal absurdity for several reasons. By accepting hundred-million-dollar fines without a full public venting of the facts, the SEC is leveling seemingly significant punishments without telling the public what the defendant is being punished for. This has essentially created a parallel or secret criminal justice system, in which both crime and punishment are adjudicated behind closed doors.

This system allows for ugly consequences in both directions. Imagine if normal criminal defendants were treated this way. Say a prosecutor and street criminal combe into a judge’s chamber and explain they’ve cooked up a deal, that the criminal doesn’t have to admit to anything or plead to any crime, but has to spend 18 months in house arrest nonetheless.

What sane judge would sign off on a deal like that without knowing exactly what the facts are? Did the criminal shoot up a nightclub and paralyze someone, or did he just sell a dimebag on the street? Is 18 months a tough sentence or a slap on the wrist? And how is it legally possible for someone to deserve an 18-month sentence without being guilty of anything?

Such deals are logical and legal absurdities, but judges have been signing off on settlements like this with Wall Street defendants for years.

Judge Rakoff blew a big hole in that practice yesterday. His ruling says secret justice is not justice, and that the government cannot hand out punishments without telling the public what the punishments are for. He wrote:

Finally, in any case like this that touches on the transparency of financial markets whose gyrations have so depressed our economy and debilitated our lives, there is an overriding public interest in knowing the truth. In much of the world, propaganda reigns, and truth is confined to secretive, fearful whispers. Even in our nation, apologists for suppressing or obscuring the truth may always be found. But the S.E.C., of all agencies, has a duty, inherent in its statutory mission, to see that the truth emerges; and if it fails to do so, this Court must not, in the name of deference or convenience, grant judicial enforcement to the agency's contrivances.

Notice the reference to how things are “in much of the world,” a subtle hint that the idea behind this ruling is to prevent a slide into third-world-style justice.

The origins and future of Occupy Wall Street

Mattathias Schwartz, writing for the New Yorker, traces the genesis of Occupy Wall Street, identifies a few individuals — such as Adbusters‘ Kalle Lasn and Micah M White — who certainly had a catalytic role in the movement’s formation, but finds that so far, it remains leaderless.

Those who were around at the beginning of the Occupy Wall Street movement talk about the old “vertical” left versus the new “horizontal” one. By “vertical,” they mean hierarchy and its trappings—leaders, demands, and issue-specific rallies. They mean social change as laid out by Saul Alinsky’s “Rules for Radicals” and Barack Obama’s “Dreams from My Father,” where outside organizers spur communities to action. “Horizontal” means leaderless—like the 1999 W.T.O. protests in Seattle, the Arab Spring, and even the Tea Party. Anyone can show up at a general assembly and claim a piece of the movement. This lets people feel important immediately, and gives them implicit permission to take action. It also gives a disproportionate amount of power to people like Sage [a homeless New Yorker who scornfully calls his fellow Zuccotti Park occupants, “tourists”].

One influence that is often cited by the movement is open-source software, such as Linux, an operating system that competes with Microsoft Windows and Apple’s OS but doesn’t have an owner or a chief engineer. A programmer named Linus Torvalds came up with the idea. Thousands of unpaid amateurs joined him and then eventually organized into work groups. Some coders have more influence than others, but anyone can modify the software and no one can sell it. According to Justine Tunney, who continues to help run OccupyWallSt.org, “There is leadership in the sense of deference, just as people defer to Linus Torvalds. But the moment people stop respecting Torvalds, they can fork it”—meaning copy what’s been built and use it to build something else.

In mid-October, supporters in Tokyo, Sydney, Madrid, and London held rallies; encampments sprang up in almost every major American city. Nearly all of them modelled themselves on the New York City General Assembly: with no official leaders, rotating facilitators, and no fixed set of demands. Today, endorsements of the Occupy movement can be found everywhere, from anarchist graffiti on bank walls to Al Gore’s Twitter feed. On a rain-smeared cardboard sign near the shattered window of an Oakland coffee shop that had been destroyed by a cadre of anarchists during a nighttime clash with police, someone wrote, “We’re sorry, this does not represent us.” Below that, someone else wrote, “Speak for yourself.”

At times, horizontalism can feel like utopian theatre. Its greatest invention is the “people’s mike,” which starts when someone shouts, “Mike check!” Then the crowd shouts, “Mike check!,” and then phrases (phrases!) are transmitted (are transmitted!) through mass chanting (through mass chanting!). In the same way that poker ritualizes capitalism and North Korea’s mass games ritualize totalitarianism, the people’s mike ritualizes horizontalism. The problem, though, comes when multiple people try to summon the mike simultaneously. Then it can feel a lot like anarchy.

The politics of the occupation run parallel to the mainstream left—the people’s mike was used to shout down Michele Bachmann and Governor Scott Walker, of Wisconsin, in early November. But, in the end, the point of Occupy Wall Street is not its platform so much as its form: people sit down and hash things out instead of passing their complaints on to Washington. “We are our demands,” as the slogan goes. And horizontalism seems made for this moment. It relies on people forming loose connections quickly—something that modern technology excels at.

Events in New York seemed to bear out Lasn’s hunch that the temporary eviction of the protesters from Zuccotti Park was an opportunity rather than a defeat. The organizers were quickly able to regroup and agree that they should return to the park, despite the newly enforced ban on tents. Last Thursday, the movement mounted one of its largest protests to date. Demonstrators tried to shut down the New York Stock Exchange (they failed), organized a sit-in at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge, and tussled with police in Zuccotti Park. More than two hundred people were arrested. Similar Day of Action protests temporarily blocked bridges in Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Houston, Milwaukee, Portland, and Philadelphia.

No matter what happens next, the movement’s center is likely to shift from the N.Y.C.G.A. [New York City General Assembly], just as it shifted from Adbusters, and form somewhere else, around some other circle of people, ideas, and plans. “This could be the greatest thing that I work on in my life,” Justine Tunney, of OccupyWallSt.org, said. “But the movement will have other Web sites. Over the coming weeks and months, as other occupations become more prominent, ours will slowly become irrelevant.” She sounded as though the irrelevance of her project were both inevitable and desirable. “We can’t hold on to any of that authority,” she continued. “We don’t want to.”

#OWS: Movement surges 10% online since Zuccotti eviction

Micah Sifry writes: A week ago, early Tuesday morning November 15th, New York City police forcibly evicted the Occupy Wall Street protest encampment at Zuccotti Park. Since then, there’s been an interesting shift in how some key observers in the mainstream media talk about the movement. For example, David Carr, an influential media columnist for the New York Times, wrote yesterday as if the Occupy movement had essentially ended, with no recognition that there are still many other cities and campuses with physical occupations underway. “A tipping point is at hand,” he intoned about the movement, “now that it is not gathered around campfires.” He added, darkly, “When the spectacle disappears reporters often fold up their tents as well.”

Not to pick on Carr, whose column and work I often enjoy, but since when did reporters treat political movements like passing fads? The Times, like many other newspapers, has given plenty of coverage to the Tea Party movement–even when the available data suggested that the Tea Party had nowhere as big a following on the ground as its media presence and polling numbers suggested.

Interestingly enough, since last Tuesday’s eviction in NYC, support for the overall Occupy Wall Street movement has risen significantly online.

News organizations complain about treatment during protests

The New York Times reports: A cross-section of 13 news organizations in New York City lodged complaints on Monday about the New York Police Department’s treatment of journalists covering the Occupy Wall Street movement. Separately, 10 press clubs, unions and other groups that represent journalists called for an investigation and said they had formed a coalition to monitor police behavior going forward.

Monday’s actions were prompted by a rash of incidents on Nov. 15, when police officers impeded and even arrested reporters during and after the evictions of Occupy Wall Street protesters from Zuccotti Park, the birthplace of the two-month-old movement.

At a news conference after the park was cleared that day, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg defended the police behavior, saying that the media were kept away “to prevent a situation from getting worse and to protect members of the press.”

The news organizations said in a joint letter to the Police Department that officers had clearly violated their own procedures by threatening, arresting and injuring reporters and photographers. The letter said there were “numerous inappropriate, if not unconstitutional, actions and abuses” by the police against both “credentialed and noncredentialed journalists in the last few days.” It requested an immediate meeting with the city’s police commissioner, Raymond W. Kelly, and his chief spokesman, Paul J. Browne.

The letter was written by George Freeman, vice president and assistant general counsel for The New York Times Company, and signed by representatives for The Associated Press, The New York Post, The Daily News, Thomson Reuters, Dow Jones & Company, and three local television stations, WABC, WCBS and WNBC. It was also signed by representatives for the National Press Photographers Association, New York Press Photographers Association, Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, and the New York Press Club.

Life after occupation

Arun Gupta visits Mobile, Alabama and Chicago, and asks: Can an occupation movement survive if it no longer occupies a space?

Emily Schuler, a Mobile native and college student, says the Occupy movement made her rethink her place in society, calling it “one of the best things that has ever happened to me.” Schuler says, “I love Mobile, but it’s ultra-conservative.” She explains, “I always felt like the black sheep because I sensed that the way the world was working was not good … There is a lot of pain and suffering. I think it has a lot to do with the way the system works. Because right now it’s profit over people. And it should be people over profit.”

To the world-weary in New York, a silent protest and proposition that the American system values “profit over people” may seem prosaic. And it would be prosaic were it not happening in a place like Mobile, Ala., and all over the United States. Dozens of occupiers have told us this movement is an “awakening” for them or for others.

One eye-opening aspect of our evening with Occupy Mobile was that none of these people knew each other a month before. The movement has created a new political community virtually overnight.

“We all felt alone,” Chelsy Wilson says. “Now we know that’s not the case. We’re going to try to reach out to other people who feel this wa … People say they have a new hope for Mobile. A lot of us were looking for jobs outside the city, we wanted to move away as fast as we could, and a lot of us have changed our minds. We want to stay here now.”

In smaller, conservative cities, the creation of a new community may be success enough for the movement, enabling a new network to consolidate and spread its message without a public encampment. But for larger cities that already have a strong progressive presence, the experience of Occupy Chicago is more relevant — and more sobering.

Occupy Chicago is forging ahead with maintaining a public presence despite never having established an occupation in the first place. It’s not for lack of trying. On two consecutive Saturdays in mid-October, Occupy Chicago tried to take Grant Park, known for Chicago’s head-bashing police plying their trade during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

On the day of the second action, Oct. 22, we caught up with the protest as it was marching to the horse, a statue that provided the rally cry, “Take the horse.” It was impressive compared to New York. A march some 3,000 strong, bullhorns, banners, resounding chants and marshals providing a buffer from the police. Occupy Chicago felt like any of hundreds of demonstrations I’ve been on in the last 20 years. To be fair, the energy and stakes were higher, but it seemed like protest as usual. It was far better organized than Occupy Wall Street’s chaotic peregrinations — and that was the problem.

In New York, Occupy Wall Street actions surge with electricity. No one quite seems in control because everyone is in control. Amoebic blobs of protesters break off and take the streets. Chants are thrown out, and the hive mind picks a winner. It is atavistic, often lacking signs, denied sound systems and shunning permits, but powered by hearts, lungs and passion. Exciting and unpredictable, it attracted greenhorns, drove the cops nuts, paralyzed Bloomberg for weeks and captured the world’s attention. That was why it worked and why the boot came down in the end.

In Chicago, the first time protesters tried to take the space on Oct. 15, 175 people were arrested. We were there for the second round of arrests of about 130 people. I talked to Jan Rodolfo, a 36-year-old oncology nurse and National Nurses United staff member. While preparing to be arrested along with other union members and scores of others, Rodolfo said Occupy Chicago needed “a permanent encampment because it allows the movement to grow by creating a central place for people to come. ”

Another activist said, “It would have been a big victory for the students, unions and other groups putting their efforts into the movement.”

It wouldn’t have just been a victory; it would have created a different movement. What made occupations in New York City and other cities so successful is that they brought new people into the movement in droves. Chicago has strong networks of activists, unionists and community groups, which are all involved in the Occupy movement. What they were missing was crucial: the people who were previously non-political.

The threat of solidarity — when power becomes afraid of the people

Martin Luther King Jr leading civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, 1965

Students lock arms before police assault, University of California at Berkeley, November 9, 2011

After a police assault (shown in the video above) on non-violent student protesters — whose only arms were the ones they interlocked — Robert Birgeneau, the chancellor at Berkeley, issued a statement saying:

It is unfortunate that some protesters chose to obstruct the police by linking arms and forming a human chain to prevent the police from gaining access to the tents. This is not non-violent civil disobedience. By contrast, some of the protesters chose to be arrested peacefully; they were told to leave their tents, informed that they would be arrested if they did not, and indicated their intention to be arrested. They did not resist arrest or try physically to obstruct the police officers’ efforts to remove the tent. These protesters were acting in the tradition of peaceful civil disobedience, and we honor them.

What Birgeneau objects to is resistance in any form and interlocking arms in defiance of an advancing line of police is indeed an act of resistance.

But more than that, it is an act of solidarity and nothing threatens institutional power more than unity among ordinary people.

When burly police officers thrust night sticks into the chests of young students, this is not simply what is euphemistically called a “show of force,” but instead seems to be a display of “forward panic.”

In the kind of police violence that sociologist Randall Collins has dubbed forward panic, a cauldron of pent up tension suddenly erupts. Among Collins’ insights is that because people (including police and soldiers) universally have high-threshold inhibitions that restrain them from becoming violent, when those inhibitions suddenly fall away, the targets of violence will most often be those who are perceived as weak, unwilling or incapable of hitting back. Fear targets the easiest opponent.

This is the micro-social context in which the police lash out, but at the same time there is a broader context that fuels the fear of those who have been invested with the power of the state.

In the face of mass resistance, the primary line of defense for the police is not their weapons or shields — it is an idea already under challenge: that the state is more powerful than the people. And once the fault-lines in that idea have been exposed, the power equation is in jeopardy of suddenly being reversed.

Over the last twelves months, in the Middle East, in Europe, and now in the United States, the seeds have already been planted which could grow into the most dangerous idea that ever swept the world: that we have a greater interest in uniting than we do in being set apart; that what we might gain together will far exceed what we can achieve alone.

Human solidarity — this is what now threatens governments, corporations and every concentration of power.

* * *

Protesters in New York today were joined by one former police officer who sees that it his duty to stand with the people: Retired Police Captain Raymond Lewis from Philadelphia.

This afternoon, Captain Lewis was marched away in cuffs after being arrested by the NYPD.

Who is Occupy Wall Street? Protesters speak out on why they joined

Matthew Bolton, 30, professor of political science at Pace University:

Nicole Carty, 23, content manager for a website:

Charles Jenkins, 52, an officer with the Transport Workers Union Local 100:

Was the New York Times embedded with the NYPD prior to the #OWS raid?

Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism writes: A longstanding NC reader and lower Manhattan resident e-mailed me:

I was curious about the first couple of pictures in this set from the NY Times. How were they able to get pictures of the NYPD gathering by South Street Seaport, before the raid?

I was following the events closely on Twitter last night. the first notice of the pending love came from a tweet by the muscian Questo, who announced he had just driven by thousands of police in riot gear by South Street.

Various tweets among #OWS folks debated the significance of this and then the NYPD was spotted moving, the emergency #OWS tweet went out and I also got an email on it. At that point, no press were anywhere near Zuccotti Park nor were any covering it on Twitter. After the #OWS emergency notice, all sorts of people rushed to the scene, including the press.

Seems strange, then, that the NY Times photographer knew to be at this secret location.

Also strange, this article by the NY Times on the chain of events leading up to the raid includes a number of factual details that don’t appear to come from any quotes or press conferences, such as the secret planning that only the top brass knew about. This article has details about where the NYPD gathered pre-raid and details about the status of the park as the raid was beginning. How did the report get this information? Was he or she there? Were they tipped off before any of the other press?

If so, what does this say about the relationship between the NY Times and the Bloomberg administration, as well as the independence of the NY Times reporting?

In the photo series, the high resolution image from South Street Seaport is indeed a bit sus, unless the NYPD has started memorializing its operations for the benefit of posterity and favored media outlets. And in the background story on the raid, I was troubled by how fawning it was, a classic example of stenography masquerading as reporting. The brilliant tactical execution by New York’s finest! And the only people who were manhandled clearly deserved it! This characterization of a raid deliberately staged well out of public view, where there have been reports of the use of tear gas, pepper spray, and unnecessary roughing up, was indirectly confirmed by the punching of a woman on camera today whose offense seemed to be demanding access to the park loudly and having court papers to back her stance.

A Raid on the First Amendment: New York’s assault on press freedom

John Nichols writes: The dark-of-night raid on New York City’s Zuccotti Park was not merely an assault on the Occupy Wall Street movement. It was an assault on the underpinnings of the First Amendment to the Constitution, an amendment that was outlined and approved by the First Congress of the United States at No. 26 Wall Street in 1789.

That amendment, which was written to empower citizens to challenge and prevent the rise of a totalitarian state, recognized basic freedoms that were essential to the defense of liberty. Among these are, of course, the right to speak freely and to embrace the religious ideals of one’s choice.

But from a standpoint of pushing back against power, however, the rights to assemble and to petition for the redress of grievances are fundamental. And those rights were clearly assaulted early Tuesday morning.

So, too, was another right: the right to a free press.

Why does the right to a free press matter so much? Because, as the founders knew, no experiment in democracy could ever be anything more than that—an experiment—if the people don’t know what is being done in their name by those in positions of authority. “A popular Government without popular information or the means of acquiring it,” observed James Madison, “is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy or perhaps both.”

Reporting from inside the “frozen zone”

Josh Harkinson describes what he witnessed at Zuccotti Part in the early hours this morning: Nobody bothered to stop me as I strode up to the park’s northern entrance and stopped against a wall, a few yards from where police in helmets surrounded the the remaining occupiers.

Next to me, an officer was telling an important-looking guy named Eddie about “the intel we’ve had over the past couple of months” about “the severely mentally retarded, the ones that are real fucked up in the head, and have been violent in the past.” He went on: “They are a little off kilter. They’re off their meds. They haven’t had meds in 30 days.”

“I’m only 24 hours off mine,” Eddie joked.

“It’s good for you, Eddie,” the cop said. “You’ve got to come clean every once in a while.”

As the two men talked, a sweaty-faced man wearing a neon vest over a business suit walked up and started tearing protest signs off the wall.”I couldn’t wait,” he said. “Destroying things never felt so good.”

“Really,” someone said, almost inflecting the word as a question.

“They’re fucking assholes,” the guy in the suit shot back.

Another guy came up to Eddie. “How are we about hooking up the fire hydrants?” he asked. “We talkin’ to somebody?”

“Do it. Do it,” Eddie said over the roar of a garbage truck.

A few yards away, the last occupiers took turns waving a large American flag. Huddled inside the park’s makeshift kitchen, they seemed as diverse as Occupy Wall Street: There was a shaggy punk in a spiky leather jacket. A young girl in a red sweatshirt that read “Unity.” Clean-shaven guys wearing glasses. A shirtless occupier named Ted Hall, who has led an effort to hone the movement’s “visions and goals.” All of them surrounded a smaller group of occupiers who’d chained their necks to a pole.

A white-shirted officer moved in with a bullhorn. “If you don’t leave the park you are subject to arrest. Now is your opportunity to leave the park.”

Nobody budged. As a lone drum pounded, I climbed up on the wall to get a better view.

“Can I help you?” an burly officer asked me, his helpfulness belied by his scowl.

“I’m a reporter,” I told him.

“This is a frozen zone, all right?” he said, using a term I’d never heard before. “Just like them, you have to leave the area. If you do not, you will be subject to arrest.”

By then, riot police were moving in, indiscriminately dousing the peaceful protesters with what looked like pepper spray or some sort of gas. As people yelled and screamed and cried, I tried to stay calm.

“I promise to leave once the arrests are done,” I replied.

“No, you are going to leave now.”

He grabbed my arm and began dragging me off. My shoes skidded across the park’s slimy granite floor. All around me, zip-cuffed occupiers writhed on the ground beneath a fog of chemicals.

“I just want to witness what is going on here,” I yelped.

“You can witness it with the rest of the press,” he said. Which, of course, meant not witnessing it.

“Why are you excluding the press from observing this?” I asked.

“Because this is a frozen zone.”