Category Archives: Life

Video: George Monbiot on rewilding the world

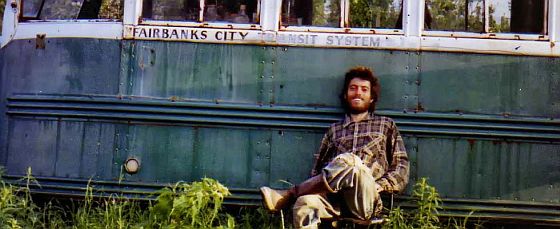

How Christopher McCandless died

Jon Krakauer writes: Twenty-one years ago this month, on September 6, 1992, the decomposed body of Christopher McCandless was discovered by moose hunters just outside the northern boundary of Denali National Park. He had died inside a rusting bus that served as a makeshift shelter for trappers, dog mushers, and other backcountry visitors. Taped to the door was a note scrawled on a page torn from a novel by Nikolai Gogol:

ATTENTION POSSIBLE VISITORS.

S.O.S.

I NEED YOUR HELP. I AM INJURED, NEAR DEATH, AND TOO WEAK TO HIKE OUT OF HERE. I AM ALL ALONE, THIS IS NO JOKE. IN THE NAME OF GOD, PLEASE REMAIN TO SAVE ME. I AM OUT COLLECTING BERRIES CLOSE BY AND SHALL RETURN THIS EVENING. THANK YOU,

CHRIS McCANDLESS

AUGUST ?From a cryptic diary found among his possessions, it appeared that McCandless had been dead for nineteen days. A driver’s license issued eight months before he perished indicated that he was twenty-four years old and weighed a hundred and forty pounds. After his body was flown out of the wilderness, an autopsy determined that it weighed sixty-seven pounds and lacked discernible subcutaneous fat. The probable cause of death, according to the coroner’s report, was starvation.

In “Into the Wild,” the book I wrote about McCandless’s brief, confounding life, I came to a different conclusion. I speculated that he had inadvertently poisoned himself by eating seeds from a plant commonly called wild potato, known to botanists as Hedysarum alpinum. According to my hypothesis, a toxic alkaloid in the seeds weakened McCandless to such a degree that it became impossible for him to hike out to the highway or hunt effectively, leading to starvation. Because Hedysarum alpinum is described as a nontoxic species in both the scientific literature and in popular books about edible plants, my conjecture was met with no small amount of derision, especially in Alaska.

I’ve received thousands of letters from people who admire McCandless for his rejection of conformity and materialism in order to discover what was authentic and what was not, to test himself, to experience the raw throb of life without a safety net. But I’ve also received plenty of mail from people who think he was an idiot who came to grief because he was arrogant, woefully unprepared, mentally unbalanced, and possibly suicidal. Most of these detractors believe my book glorifies a senseless death. As the columnist Craig Medred wrote in the Anchorage Daily News in 2007,

“Into the Wild” is a misrepresentation, a sham, a fraud. There, I’ve finally said what somebody has needed to say for a long time …. Krakauer took a poor misfortunate prone to paranoia, someone who left a note talking about his desire to kill the “false being within,” someone who managed to starve to death in a deserted bus not far off the George Parks Highway, and made the guy into a celebrity. Why the author did that should be obvious. He wanted to write a story that would sell.

The debate over why McCandless perished, and the related question of whether he is worthy of admiration, has been smoldering, and occasionally flaring, for more than two decades now. But last December, a writer named Ronald Hamilton posted a paper on the Internet that brings fascinating new facts to the discussion. Hamilton, it turns out, has discovered hitherto unknown evidence that appears to close the book on the cause of McCandless’s death. [Continue reading…]

Video: The meaning of death

Meaning is healthier than happiness

Emily Esfahani Smith writes: For at least the last decade, the happiness craze has been building. In the last three months alone, over 1,000 books on happiness were released on Amazon, including Happy Money, Happy-People-Pills For All, and, for those just starting out, Happiness for Beginners.

One of the consistent claims of books like these is that happiness is associated with all sorts of good life outcomes, including — most promisingly — good health. Many studies have noted the connection between a happy mind and a healthy body — the happier you are, the better health outcomes we seem to have. In a meta-analysis (overview) of 150 studies on this topic, researchers put it like this: “Inductions of well-being lead to healthy functioning, and inductions of ill-being lead to compromised health.”

But a new study, just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) challenges the rosy picture. Happiness may not be as good for the body as researchers thought. It might even be bad.

Of course, it’s important to first define happiness. A few months ago, I wrote a piece called “There’s More to Life Than Being Happy” about a psychology study that dug into what happiness really means to people. It specifically explored the difference between a meaningful life and a happy life. [Continue reading…]

Spiders have personalities

Wired: Armed with branch cutters, pillowcases, and a vibrator, a team of scientists has discovered how social spiders in India assign chores within their colonies – and they say it has to do with spider personalities.

Big and bold? Go get that grasshopper! Slightly more timid? Maybe stay home, take care of the brood, and clean the nest or something.

“Bolder individuals were the ones that engaged in prey attack,” said Lena Grinsted, now a postdoc at the University of Sussex, and coauthor of the study describing the spiders that appeared July 30 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. “We hypothesize that the ones who don’t participate in prey attack participate in brood care, but it’s something we haven’t tested yet.”

The researchers say their findings support the idea that spiders have personalities. Sure, they’re not as complex as human personalities, but they’re defined by behavior differences that are consistent over time and context. In this study, scientists tested whether the division of labor was related to personality in the social spiders Stegodyphus sarasinorum. [Continue reading…]

Dolphins gain unprecedented protection in India

Deutsche Welle reports: India has officially recognized dolphins as non-human persons, whose rights to life and liberty must be respected. Dolphin parks that were being built across the country will instead be shut down.

India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests has advised state governments to ban dolphinariums and other commercial entertainment that involves the capture and confinement of cetacean species such as orcas and bottlenose dolphins. In a statement, the government said research had clearly established cetaceans are highly intelligent and sensitive, and that dolphins “should be seen as ‘non-human persons’ and as such should have their own specific rights.”

The move comes after weeks of protest against a dolphin park in the state of Kerala and several other marine mammal entertainment facilities which were to be built this year. Animal welfare advocates welcomed the decision.

“This opens up a whole new discourse of ethics in the animal protection movement in India,” said Puja Mitra from the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organizations (FIAPO). Mitra is a leading voice in the Indian movement to end dolphin captivity.

“The scientific evidence we provided during the campaign talked about cetacean intelligence and introduced the concept of non-human persons,” she said in an interview with DW.

Indiais the fourth country in the world to ban the capture and import of cetaceans for the purpose of commercial entertainment – along with Costa Rica, Hungary, and Chile. [Continue reading…]

The slaughter of migrating songbirds

If there was a league table of suffering, designed to remind us of the issues that deserve the greatest share of human concern, the plight of songbirds might not come high on the list.

Yet rather than attempting to adjudicate how concern should be sliced and apportioned, maybe we should instead reflect on the insidious effects of indifference.

Looking at the world often feels like staring at a raw wound — our instincts tell us to turn away. But this turning away, quickly becomes a habit and the desire to insulate ourselves from pain ends up as a way of shutting out life.

Jonathan Franzen writes: In a bird market in the Mediterranean tourist town of Marsa Matruh, Egypt, I was inspecting cages crowded with wild turtledoves and quail when one of the birdsellers saw the disapproval in my face and called out sarcastically, in Arabic: “You Americans feel bad about the birds, but you don’t feel bad about dropping bombs on someone’s homeland.”

I could have answered that it’s possible to feel bad about both birds and bombs, that two wrongs don’t make a right. But it seemed to me that the birdseller was saying something true about the problem of nature conservation in a world of human conflict, something not so easily refuted. He kissed his fingers to suggest how good the birds tasted, and I kept frowning at the cages.

To a visitor from North America, where bird hunting is well regulated and only naughty farm boys shoot songbirds, the situation in the Mediterranean is appalling: Every year, from one end of it to the other, hundreds of millions of songbirds and larger migrants are killed for food, profit, sport, and general amusement. The killing is substantially indiscriminate, with heavy impact on species already battered by destruction or fragmentation of their breeding habitat. Mediterraneans shoot cranes, storks, and large raptors for which governments to the north have multimillion-euro conservation projects. All across Europe bird populations are in steep decline, and the slaughter in the Mediterranean is one of the causes.

Italian hunters and poachers are the most notorious; for much of the year, the woods and wetlands of rural Italy crackle with gunfire and songbird traps. The food-loving French continue to eat ortolan buntings illegally, and France’s singularly long list of huntable birds includes many struggling species of shorebirds. Songbird trapping is still widespread in parts of Spain; Maltese hunters, frustrated by a lack of native quarry, blast migrating raptors out of the sky; Cypriots harvest warblers on an industrial scale and consume them by the plateful, in defiance of the law. [Continue reading…]

Video: Birds of paradise

The cancer of optimism

Haider Javed Warraich writes: Physicians are thought to be the harbingers of bad tidings, the people who use cold words like “prognosis.” But studies show that they are just as capable of emotions as their patients are. According to a study published in 2000 in the British medical journal BMJ, about two-thirds of doctors overestimate the survival of terminally ill patients.

A study of cancer patients and their doctors in the Annals of Internal Medicine a year later found that many doctors didn’t quite tell patients the truth about their prognosis. Doctors were up front about their patients’ estimated survival 37 percent of the time; refused to give any estimate 23 percent of the time; and told patients something else 40 percent of the time. Around 70 percent of the discrepant estimates were overly optimistic.

This optimism is far from harmless. It drives doctors to endorse treatments that most likely won’t save patients’ lives, but may cause them unnecessary suffering and inch their families toward medical bankruptcy.

One source of this optimism is pop culture, which frequently depicts heroic recoveries from seemingly life-threatening situations. Another is the medical school experience. What motivates weary medical students is the hope that one day interventions they perform will save lives, heal families and enact cosmic good.

Later, our judgment becomes clouded as we build relationships with patients, share their fears and anxieties, cherish their small victories and celebrations and hope that there may still be a way, however unlikely, they can make it to their grandson’s bar mitzvah.

And yet studies have shown that patients almost universally prefer to be told the truth. If physicians cannot deliver the hard facts, not only do they deprive their patients of crucial information, but they also delay the conversation about introducing palliative care.

Modern palliative care originated in response to the proliferation of new treatments and resuscitation technologies. Keeping a patient “alive” became easier. And yet the definition of “alive” suffered — with quality of life frequently being usurped by length of life. [Continue reading…]

The scope and the scale of animal intelligence

Ayumu

As everyone knows (or should know), you don’t have to be smart to get rich. The aggregation of power is not coterminous with the concentration of talent — that is, other than the talent for accumulating power.

In spite of this, there is a human prejudice which, observing our species’ dominion across the world, assumes that given that human beings exert so much power — enough to have set in train the Anthropocene, a new epoch in the planet’s history — it goes without saying that our intelligence exceeds that of every other creature.

Even so, given that we seem to be intent on setting our own home on fire, that’s reason enough to question our intelligence. It also turns out that based on our own metrics, we can be outwitted by animals that we otherwise regard as having lesser intelligence.

Frans de Waal writes: Who is smarter: a person or an ape? Well, it depends on the task. Consider Ayumu, a young male chimpanzee at Kyoto University who, in a 2007 study, put human memory to shame. Trained on a touch screen, Ayumu could recall a random series of nine numbers, from 1 to 9, and tap them in the right order, even though the numbers had been displayed for just a fraction of a second and then replaced with white squares. [See video below.]

I tried the task myself and could not keep track of more than five numbers—and I was given much more time than the brainy ape. In the study, Ayumu outperformed a group of university students by a wide margin. The next year, he took on the British memory champion Ben Pridmore and emerged the “chimpion.”

How do you give a chimp — or an elephant or an octopus or a horse — an IQ test? It may sound like the setup to a joke, but it is actually one of the thorniest questions facing science today. Over the past decade, researchers on animal cognition have come up with some ingenious solutions to the testing problem. Their findings have started to upend a view of humankind’s unique place in the universe that dates back at least to ancient Greece.

Aristotle’s idea of the scala naturae, the ladder of nature, put all life-forms in rank order, from low to high, with humans closest to the angels. During the Enlightenment, the French philosopher René Descartes, a founder of modern science, declared that animals were soulless automatons. In the 20th century, the American psychologist B.F. Skinner and his followers took up the same theme, painting animals as little more than stimulus-response machines. Animals might be capable of learning, they argued, but surely not of thinking and feeling. The term “animal cognition” remained an oxymoron.

A growing body of evidence shows, however, that we have grossly underestimated both the scope and the scale of animal intelligence. Can an octopus use tools? Do chimpanzees have a sense of fairness? Can birds guess what others know? Do rats feel empathy for their friends? Just a few decades ago we would have answered “no” to all such questions. Now we’re not so sure. [Continue reading…]

For gangsta gardeners, growing your own food is like printing your own money

Video: On being wrong

There’s more to life than being happy

Emily Esfahani Smith writes: In September 1942, Viktor Frankl, a prominent Jewish psychiatrist and neurologist in Vienna, was arrested and transported to a Nazi concentration camp with his wife and parents. Three years later, when his camp was liberated, most of his family, including his pregnant wife, had perished — but he, prisoner number 119104, had lived. In his bestselling 1946 book, Man’s Search for Meaning, which he wrote in nine days about his experiences in the camps, Frankl concluded that the difference between those who had lived and those who had died came down to one thing: Meaning, an insight he came to early in life. When he was a high school student, one of his science teachers declared to the class, “Life is nothing more than a combustion process, a process of oxidation.” Frankl jumped out of his chair and responded, “Sir, if this is so, then what can be the meaning of life?”

As he saw in the camps, those who found meaning even in the most horrendous circumstances were far more resilient to suffering than those who did not. “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing,” Frankl wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning, “the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Frankl worked as a therapist in the camps, and in his book, he gives the example of two suicidal inmates he encountered there. Like many others in the camps, these two men were hopeless and thought that there was nothing more to expect from life, nothing to live for. “In both cases,” Frankl writes, “it was a question of getting them to realize that life was still expecting something from them; something in the future was expected of them.” For one man, it was his young child, who was then living in a foreign country. For the other, a scientist, it was a series of books that he needed to finish. Frankl writes:

This uniqueness and singleness which distinguishes each individual and gives a meaning to his existence has a bearing on creative work as much as it does on human love. When the impossibility of replacing a person is realized, it allows the responsibility which a man has for his existence and its continuance to appear in all its magnitude. A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the “why” for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any “how.”

In 1991, the Library of Congress and Book-of-the-Month Club listed Man’s Search for Meaning as one of the 10 most influential books in the United States. It has sold millions of copies worldwide. Now, over twenty years later, the book’s ethos — its emphasis on meaning, the value of suffering, and responsibility to something greater than the self — seems to be at odds with our culture, which is more interested in the pursuit of individual happiness than in the search for meaning. “To the European,” Frankl wrote, “it is a characteristic of the American culture that, again and again, one is commanded and ordered to ‘be happy.’ But happiness cannot be pursued; it must ensue. One must have a reason to ‘be happy.'”

According to Gallup, the happiness levels of Americans are at a four-year high — as is, it seems, the number of best-selling books with the word “happiness” in their titles. At this writing, Gallup also reports that nearly 60 percent all Americans today feel happy without a lot of stress or worry. On the other hand, according to the Center for Disease Control, about 4 out of 10 Americans have not discovered a satisfying life purpose. Forty percent either do not think their lives have a clear sense of purpose or are neutral about whether their lives have purpose. Nearly a quarter of Americans feel neutral or do not have a strong sense of what makes their lives meaningful. Research has shown that having purpose and meaning in life increases overall well-being and life satisfaction, improves mental and physical health, enhances resiliency, enhances self-esteem, and decreases the chances of depression. On top of that, the single-minded pursuit of happiness is ironically leaving people less happy, according to recent research. “It is the very pursuit of happiness,” Frankl knew, “that thwarts happiness.” [Continue reading…]

Inside the mind of an octopus

Sy Montgomery: “Meeting an octopus,” writes [professor of philosophy, Peter] Godfrey-Smith, “is like meeting an intelligent alien.” Their intelligence sometimes even involves changing colors and shapes. One video online shows a mimic octopus alternately morphing into a flatfish, several sea snakes, and a lionfish by changing color, altering the texture of its skin, and shifting the position of its body. Another video shows an octopus materializing from a clump of algae. Its skin exactly matches the algae from which it seems to bloom — until it swims away.

For its color palette, the octopus uses three layers of three different types of cells near the skin’s surface. The deepest layer passively reflects background light. The topmost may contain the colors yellow, red, brown, and black. The middle layer shows an array of glittering blues, greens, and golds. But how does an octopus decide what animal to mimic, what colors to turn? Scientists have no idea, especially given that octopuses are likely colorblind.

But new evidence suggests a breathtaking possibility. Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory and University of Washington researchers found that the skin of the cuttlefish Sepia officinalis, a color-changing cousin of octopuses, contains gene sequences usually expressed only in the light-sensing retina of the eye. In other words, cephalopods — octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid — may be able to see with their skin.

The American philosopher Thomas Nagel once wrote a famous paper titled “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” Bats can see with sound. Like dolphins, they can locate their prey using echoes. Nagel concluded it was impossible to know what it’s like to be a bat. And a bat is a fellow mammal like us — not someone who tastes with its suckers, sees with its skin, and whose severed arms can wander about, each with a mind of its own. Nevertheless, there are researchers still working diligently to understand what it’s like to be an octopus.

Jennifer Mather spent most of her time in Bermuda floating facedown on the surface of the water at the edge of the sea. Breathing through a snorkel, she was watching Octopus vulgaris — the common octopus. Although indeed common (they are found in tropical and temperate waters worldwide), at the time of her study in the mid-1980s, “nobody knew what they were doing.”

In a relay with other students from six-thirty in the morning till six-thirty at night, Mather worked to find out. Sometimes she’d see an octopus hunting. A hunting expedition could take five minutes or three hours. The octopus would capture something, inject it with venom, and carry it home to eat. “Home,” Mather found, is where octopuses spend most of their time. A home, or den, which an octopus may occupy only a few days before switching to a new one, is a place where the shell-less octopus can safely hide: a hole in a rock, a discarded shell, or a cubbyhole in a sunken ship. One species, the Pacific red octopus, particularly likes to den in stubby, brown, glass beer bottles.

One octopus Mather was watching had just returned home and was cleaning the front of the den with its arms. Then, suddenly, it left the den, crawled a meter away, picked up one particular rock and placed the rock in front of the den. Two minutes later, the octopus ventured forth to select a second rock. Then it chose a third. Attaching suckers to all the rocks, the octopus carried the load home, slid through the den opening, and carefully arranged the three objects in front. Then it went to sleep. What the octopus was thinking seemed obvious: “Three rocks are enough. Good night!”

The scene has stayed with Mather. The octopus “must have had some concept,” she said, “of what it wanted to make itself feel safe enough to go to sleep.” And the octopus knew how to get what it wanted: by employing foresight, planning — and perhaps even tool use. Mather is the lead author of Octopus: The Ocean’s Intelligent Invertebrate, which includes observations of octopuses who dismantle Lego sets and open screw-top jars. Coauthor Roland Anderson reports that octopuses even learned to open the childproof caps on Extra Strength Tylenol pill bottles — a feat that eludes many humans with university degrees.

In another experiment, Anderson gave octopuses plastic pill bottles painted different shades and with different textures to see which evoked more interest. Usually each octopus would grasp a bottle to see if it were edible and then cast it off. But to his astonishment, Anderson saw one of the octopuses doing something striking: she was blowing carefully modulated jets of water from her funnel to send the bottle to the other end of her aquarium, where the water flow sent it back to her. She repeated the action twenty times. By the eighteenth time, Anderson was already on the phone with Mather with the news: “She’s bouncing the ball!”

This octopus wasn’t the only one to use the bottle as a toy. Another octopus in the study also shot water at the bottle, sending it back and forth across the water’s surface, rather than circling the tank. Anderson’s observations were reported in the Journal of Comparative Psychology. “This fit all the criteria for play behavior,” said Anderson. “Only intelligent animals play — animals like crows and chimps, dogs and humans.” [Continue reading…]