Edward Mendelson writes: Every technological revolution coincides with changes in what it means to be a human being, in the kinds of psychological borders that divide the inner life from the world outside. Those changes in sensibility and consciousness never correspond exactly with changes in technology, and many aspects of today’s digital world were already taking shape before the age of the personal computer and the smartphone. But the digital revolution suddenly increased the rate and scale of change in almost everyone’s lives. Elizabeth Eisenstein’s exhilaratingly ambitious historical study The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (1979) may overstate its argument that the press was the initiating cause of the great changes in culture in the early sixteenth century, but her book pointed to the many ways in which new means of communication can amplify slow, preexisting changes into an overwhelming, transforming wave.

In The Changing Nature of Man (1956), the Dutch psychiatrist J.H. van den Berg described four centuries of Western life, from Montaigne to Freud, as a long inward journey. The inner meanings of thought and actions became increasingly significant, while many outward acts became understood as symptoms of inner neuroses rooted in everyone’s distant childhood past; a cigar was no longer merely a cigar. A half-century later, at the start of the digital era in the late twentieth century, these changes reversed direction, and life became increasingly public, open, external, immediate, and exposed.

Virginia Woolf’s serious joke that “on or about December 1910 human character changed” was a hundred years premature. Human character changed on or about December 2010, when everyone, it seemed, started carrying a smartphone. For the first time, practically anyone could be found and intruded upon, not only at some fixed address at home or at work, but everywhere and at all times. Before this, everyone could expect, in the ordinary course of the day, some time at least in which to be left alone, unobserved, unsustained and unburdened by public or familial roles. That era now came to an end.

Many probing and intelligent books have recently helped to make sense of psychological life in the digital age. Some of these analyze the unprecedented levels of surveillance of ordinary citizens, others the unprecedented collective choice of those citizens, especially younger ones, to expose their lives on social media; some explore the moods and emotions performed and observed on social networks, or celebrate the Internet as a vast aesthetic and commercial spectacle, even as a focus of spiritual awe, or decry the sudden expansion and acceleration of bureaucratic control.

The explicit common theme of these books is the newly public world in which practically everyone’s lives are newly accessible and offered for display. The less explicit theme is a newly pervasive, permeable, and transient sense of self, in which much of the experience, feeling, and emotion that used to exist within the confines of the self, in intimate relations, and in tangible unchanging objects — what William James called the “material self” — has migrated to the phone, to the digital “cloud,” and to the shape-shifting judgments of the crowd. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Attention to the Unseen

RIP Bob Paine, a keystone among ecologists

Ed Yong writes: I’m deeply saddened to learn that Bob Paine, a giant of ecology, passed away yesterday. You may not know his name, but you almost certainly know the ideas that he pioneered.

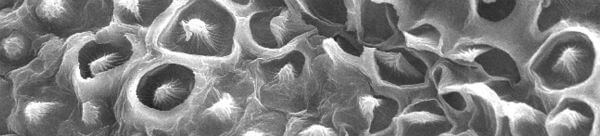

Back in 1963, Paine began prying ochre starfish off a rocky beach in Washington and hurling them into the sea. After a year, the mussels that the starfish would normally have eaten had overrun the beach, turning a wonderland of limpets, anemones, and barnacles into a monoculture of black gaping shells.

The experiment was ground-breaking. It showed that not all species are equal, and that some — like the starfish—are secret lynchpins of the natural world. Their absence can ripple outwards, triggering the rise and fall of connected species and can even reshape the landscape. For example, when sea otters vanish, the sea urchins they eat transform lush forests of kelp into desolate barrens, dooming the fish, crabs, and other animals that once lived there. Paine called these ripples “trophic cascades”, and he billed the animals behind them — the starfish, otters, and others — as “keystone species”, after the central stone that stops an arch from collapsing. These concepts are so familiar today that we take them for granted, but we didn’t always know about them. We only do because of Paine. [Continue reading…]

Theophrastus: The unsung hero of Western Science

Andrea Wulf writes: In 345 B.C.E., two men took a trip that changed the way we make sense of the natural world. Their names were Theophrastus and Aristotle, and they were staying on Lesbos, the Greek island where tens of thousands of Syrian refugees have recently landed.

Theophrastus and Aristotle were two of the greatest thinkers in ancient Greece. They set out to bring order to nature by doing something very unusual for the time: they examined living things and got their hands dirty. They turned away from Plato’s idealism and looked at the real world. Both Aristotle and Theophrastus believed that the study of nature was as important as metaphysics, politics, or mathematics. Nothing was too small or insignificant. “There is something awesome in all natural things.” Aristotle said, “inherent in each of them there is something natural and beautiful.”

Aristotle is the more famous of the two men, but Theophrastus deserves equal bidding in any history of naturalism. Born around 372 B.C.E. in Eresos, a town on the southwestern coast of Lesbos, Theophrastus was 13 years younger than Aristotle. According to Diogenes Laërtius — a biographer who wrote his Eminent Philosophers more than 400 years afterwards but who is the main source for what we know about Theophrastus’ life — Theophrastus was one of Aristotle’s pupils at Plato’s Academy. For many years they worked closely together until Aristotle’s death in 322 B.C.E. when Theophrastus became his successor at the Lyceum school in Athens and inherited his magnificent library. [Continue reading…]

Vast medieval cities hidden beneath the jungle discovered in Cambodia

The Guardian reports: Archaeologists in Cambodia have found multiple, previously undocumented medieval cities not far from the ancient temple city of Angkor Wat, the Guardian can reveal, in groundbreaking discoveries that promise to upend key assumptions about south-east Asia’s history.

The Australian archaeologist Dr Damian Evans, whose findings will be published in the Journal of Archaeological Science on Monday, will announce that cutting-edge airborne laser scanning technology has revealed multiple cities between 900 and 1,400 years old beneath the tropical forest floor, some of which rival the size of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh.

Some experts believe that the recently analysed data – captured in 2015 during the most extensive airborne study ever undertaken by an archaeological project, covering 734 sq miles (1,901 sq km) – shows that the colossal, densely populated cities would have constituted the largest empire on earth at the time of its peak in the 12th century.

Evans said: “We have entire cities discovered beneath the forest that no one knew were there – at Preah Khan of Kompong Svay and, it turns out, we uncovered only a part of Mahendraparvata on Phnom Kulen [in the 2012 survey] … this time we got the whole deal and it’s big, the size of Phnom Penh big.” [Continue reading…]

Schooled in nature

Jay Griffiths writes: In Mexico City, the cathedral – this stentorian thug of a cathedral – is sinking. Built to crush the indigenous temple beneath it, while its decrees pulverised indigenous thinking, Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral is sinking under the weight of its own brutal imposition.

Walking nearby late one night, I was captivated by music. Closer, now, and I came upon an indigenous, pre-Hispanic ceremony being danced on the pavement hard by the cathedral. Copal tree resin was burning, marigolds were scattered like living coins, people in feather headdresses and jaguar masks danced to flutes, drums, rattles and shell-bells. While each cathedral column was a Columbus colonising the site, the ceremony seemed to say: We’re still here.

A young man watched me awhile, as I was taking notes, and then approached me smiling.

‘Do you understand Nahuatl?’ he asked.

Head-shaking smile.

‘Do you want me to explain?’

‘Yes!’

He spent an hour gently unfurling each word. Abjectly poor, his worn-out shoes no longer even covered his feet and his clothes were rags, but he shone with an inner wealth, a light that was his gift, to respect the connections of the world, between people, animals, plants and the elements. He spoke of the importance of not losing the part of ourselves that touches the heart of the Earth; of listening within, and also to the natural world. Two teachers. No one has ever said it better.

‘Your spirit is your maestro interno. Your spirit brought you here. You have your gift and destiny to complete in this world. You have to align yourself in the right direction and carry on.’ And he melted away, leaving me with tears in my eyes as if I had heard a lodestar singing its own quiet truthsong.

A few days earlier, I’d been invited to the Centre for Indigenous Arts in Papantla, in the Mexican state of Veracruz, 300km east of Mexico City. The centre was celebrating the anniversary of its founding (in 2006), and promoting indigenous education: decolonised schooling. Not by chance, it is 12 October, the day when, in 1492, Christopher Columbus arrived in the so-called New World. Here, they come not to praise Columbus but to bury his legacy because – as an act of pointed protest – this date is now widely honoured as the day of indigenous resistance. [Continue reading…]

Should chimps be considered people under the law?

Jay Schwartz writes: In late 2013, the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) filed a first-ever lawsuit to free a pet chimpanzee named Tommy from the inadequate conditions provided by his owner. The NhRP, a legal group focused on animal protection, argued that Tommy is an autonomous being who is held against his will and that he is entitled to a common-law writ of habeas corpus, a legal means of determining the legality of imprisonment. Granting habeas corpus to a chimpanzee would mean viewing chimpanzees as legal persons with rights, rather than as mere things, so this case was rather controversial.

The Tommy case came to a close on December 4, 2014, as the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court’s five-judge panel ruled against the NhRP. (The state’s highest court is the Court of Appeals.) Justice Karen K. Peters, the presiding judge, wrote: “Needless to say, unlike human beings, chimpanzees cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities or be held legally accountable for their actions. In our view, it is this incapability to bear any legal responsibilities and societal duties that renders it inappropriate to confer upon chimpanzees the legal rights … that have been afforded to human beings.” [Continue reading…]

A lot of people will regard the effort to confer legal rights to non-humans as being driven by anthropomorphism. But consider the court’s argument. Could not the exact same line of reasoning be used to argue that small children or adults with developmental disabilities be deprived of legal rights? Of course, such an argument would rightly be decried as inhuman and barbaric.

Earliest evidence of fire making by prehumans in Europe found

Science News reports: Prehumans living around 800,000 years ago in what’s now southeastern Spain were, literally, trailblazers. They lit small, controlled blazes in a cave, a new study finds.

Discoveries in the cave provide the oldest evidence of fire making in Europe and support proposals that members of the human genus, Homo, regularly ignited fires starting at least 1 million years ago, say paleontologist Michael Walker of the University of Murcia in Spain and his colleagues. Fire making started in Africa (SN: 5/5/12, p. 18) and then moved north to the Middle East (SN: 5/1/04, p. 276) and Europe, the researchers conclude in the June Antiquity.

If the age estimate for the Spain find holds up, the new report adds to a “surprising number” of sites from deep in the Stone Age that retain evidence of small, intentionally lit fires, says archaeologist John Gowlett of the University of Liverpool in England.

Excavations conducted since 2011 at the Spanish cave, Cueva Negra del Estrecho del Río Quípar, have uncovered more than 165 stones and stone artifacts that had been heated, as well as about 2,300 animal-bone fragments displaying signs of heating and charring. Microscopic and chemical analyses indicate that these finds had been heated to between 400° and 600° Celsius, consistent with having been burned in a fire. [Continue reading…]

Has the quantum era has begun?

IDG News Service reports: Quantum computing’s full potential may still be years away, but there are plenty of benefits to be realized right now.

So argues Vern Brownell, president and CEO of D-Wave Systems, whose namesake quantum system is already in its second generation.

Launched 17 years ago by a team with roots at Canada’s University of British Columbia, D-Wave introduced what it called “the world’s first commercially available quantum computer” back in 2010. Since then the company has doubled the number of qubits, or quantum bits, in its machines roughly every year. Today, its D-Wave 2X system boasts more than 1,000.

The company doesn’t disclose its full customer list, but Google, NASA and Lockheed-Martin are all on it, D-Wave says. In a recent experiment, Google reported that D-Wave’s technology outperformed a conventional machine by 100 million times. [Continue reading…]

Universe is expanding up to 9% faster than we thought, say scientists

The Guardian reports: The universe is expanding faster than anyone had previously measured or calculated from theory. This is a discovery that could test part of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, a pillar of cosmology that has withstood challenges for a century.

Nasa and the European Space Agency jointly announced the universe is expanding 5% to 9% faster than predicted, a finding they reached after using the Hubble space telescope to measure the distance to stars in 19 galaxies beyond theMilky Way.

The rate of expansion did not match predictions based on measurements of radiation left over from the Big Bang that gave rise to the known universe 13.8bn years ago.

Physicist and lead author Adam Riess said: “You start at two ends, and you expect to meet in the middle if all of your drawings are right and your measurements are right.

“But now the ends are not quite meeting in the middle and we want to know why.” [Continue reading…]

Teaching ‘grit’ is bad for children, and bad for democracy

Nicholas Tampio writes: According to the grit narrative, children in the United States are lazy, entitled and unprepared to compete in the global economy. Schools have contributed to the problem by neglecting socio-emotional skills. The solution, then, is for schools to impart the dispositions that enable American children to succeed in college and careers. According to this story, politicians, policymakers, corporate executives and parents agree that kids need more grit.

The person who has arguably done more than anyone else to elevate the concept of grit in academic and popular conversations is Angela Duckworth, professor at the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania. In her new book, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, she explains the concept of grit and how people can cultivate it in themselves and others.

According to Duckworth, grit is the ability to overcome any obstacle in pursuit of a long-term project: ‘To be gritty is to hold fast to an interesting and purposeful goal. To be gritty is to invest, day after week after year, in challenging practice. To be gritty is to fall down seven times and rise eight.’ Duckworth names musicians, athletes, coaches, academics and business people who succeed because of grit. Her book will be a boon for policymakers who want schools to inculcate and measure grit.

There is a time and place for grit. However, praising grit as such makes no sense because it can often lead to stupid or mean behaviour. Duckworth’s book is filled with gritty people doing things that they, perhaps, shouldn’t. [Continue reading…]

How Neanderthal DNA helps humanity

Emily Singer writes: Early human history was a promiscuous affair. As modern humans began to spread out of Africa roughly 50,000 years ago, they encountered other species that looked remarkably like them — the Neanderthals and Denisovans, two groups of archaic humans that shared an ancestor with us roughly 600,000 years earlier. This motley mix of humans coexisted in Europe for at least 2,500 years, and we now know that they interbred, leaving a lasting legacy in our DNA. The DNA of non-Africans is made up of roughly 1 to 2 percent Neanderthal DNA, and some Asian and Oceanic island populations have as much as 6 percent Denisovan DNA.

Over the last few years, scientists have dug deeper into the Neanderthal and Denisovan sections of our genomes and come to a surprising conclusion. Certain Neanderthal and Denisovan genes seem to have swept through the modern human population — one variant, for example, is present in 70 percent of Europeans — suggesting that these genes brought great advantage to their bearers and spread rapidly.

“In some spots of our genome, we are more Neanderthal than human,” said Joshua Akey, a geneticist at the University of Washington. “It seems pretty clear that at least some of the sequences we inherited from archaic hominins were adaptive, that they helped us survive and reproduce.”

But what, exactly, do these fragments of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA do? What survival advantage did they confer on our ancestors? Scientists are starting to pick up hints. Some of these genes are tied to our immune system, to our skin and hair, and perhaps to our metabolism and tolerance for cold weather, all of which might have helped emigrating humans survive in new lands.

“What allowed us to survive came from other species,” said Rasmus Nielsen, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “It’s not just noise, it’s a very important substantial part of who we are.” [Continue reading…]

How philosophy came to disdain the wisdom of oral cultures

Justin E H Smith writes: A poet, somewhere in Siberia, or the Balkans, or West Africa, some time in the past 60,000 years, recites thousands of memorised lines in the course of an evening. The lines are packed with fixed epithets and clichés. The bard is not concerned with originality, but with intonation and delivery: he or she is perfectly attuned to the circumstances of the day, and to the mood and expectations of his or her listeners.

If this were happening 6,000-plus years ago, the poet’s words would in no way have been anchored in visible signs, in text. For the vast majority of the time that human beings have been on Earth, words have had no worldly reality other than the sound made when they are spoken.

As the theorist Walter J Ong pointed out in Orality and Literacy: Technologizing the Word (1982), it is difficult, perhaps even impossible, now to imagine how differently language would have been experienced in a culture of ‘primary orality’. There would be nowhere to ‘look up a word’, no authoritative source telling us the shape the word ‘actually’ takes. There would be no way to affirm the word’s existence at all except by speaking it – and this necessary condition of survival is important for understanding the relatively repetitive nature of epic poetry. Say it over and over again, or it will slip away. In the absence of fixed, textual anchors for words, there would be a sharp sense that language is charged with power, almost magic: the idea that words, when spoken, can bring about new states of affairs in the world. They do not so much describe, as invoke.

As a consequence of the development of writing, first in the ancient Near East and soon after in Greece, old habits of thought began to die out, and certain other, previously latent, mental faculties began to express themselves. Words were now anchored and, though spellings could change from one generation to another, or one region to another, there were now physical traces that endured, which could be transmitted, consulted and pointed to in settling questions about the use or authority of spoken language.

Writing rapidly turned customs into laws, agreements into contracts, genealogical lore into history. In each case, what had once been fundamentally temporal and singular was transformed into something eternal (as in, ‘outside of time’) and general. Even the simple act of making everyday lists of common objects – an act impossible in a primary oral culture – was already a triumph of abstraction and systematisation. From here it was just one small step to what we now call ‘philosophy’. [Continue reading…]

Genes are overrated

Nathaniel Comfort writes: In the Darwinian struggle of scientific ideas, the gene is surely among the select. It has become the foundation of medicine and the basis of vigorous biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. Media coverage of recent studies touts genes for crime, obesity, intelligence — even the love of bacon. We treat our genes as our identity. Order a home genetic-testing kit from the company 23andMe, and the box arrives proclaiming, “Welcome to you.” Cheerleaders for crispr, the new, revolutionarily simple method of editing genes, foretell designer babies, the end of disease, and perhaps even the transformation of humanity into a new and better species. When we control the gene, its champions promise, we will be the masters of our own destiny.

The gene has now found a fittingly high-profile chronicler in Siddhartha Mukherjee, the oncologist-author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning The Emperor of All Maladies, a history of cancer. The Gene’s dominant traits are historical breadth, clinical compassion, and Mukherjee’s characteristic graceful style. He calls it “an intimate history” because he shares with us his own dawning awareness of heredity and his quest to make meaning of it. The curtain rises on Kolkata, where he has gone to visit Moni, his paternal cousin, who has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. In addition to Moni, two of the author’s uncles were afflicted with “various unravelings of the mind.” Asked for a Bengali term for such inherited illness, Mukherjee’s father replies, “Abheder dosh” — a flaw in identity. Schizophrenia becomes a troubling touchstone throughout the book. But the Indian interludes are tacked onto an otherwise conventional triumphalist account of European-American genetics, written from the winners’ point of view: a history of the emperor of all molecules. [Continue reading…]

A skeptic bashing Skeptics

John Horgan, in a slightly edited version of a talk he gave recently at Northeast Conference on Science and Skepticism, writes: I hate preaching to the converted. If you were Buddhists, I’d bash Buddhism. But you’re skeptics, so I have to bash skepticism.

I’m a science journalist. I don’t celebrate science, I criticize it, because science needs critics more than cheerleaders. I point out gaps between scientific hype and reality. That keeps me busy, because, as you know, most peer-reviewed scientific claims are wrong.

So I’m a skeptic, but with a small S, not capital S. I don’t belong to skeptical societies. I don’t hang out with people who self-identify as capital-S Skeptics. Or Atheists. Or Rationalists.

When people like this get together, they become tribal. They pat each other on the back and tell each other how smart they are compared to those outside the tribe. But belonging to a tribe often makes you dumber.

Here’s an example involving two idols of Capital-S Skepticism: biologist Richard Dawkins and physicist Lawrence Krauss. Krauss recently wrote a book, A Universe from Nothing. He claims that physics is answering the old question, Why is there something rather than nothing?

Krauss’s book doesn’t come close to fulfilling the promise of its title, but Dawkins loved it. He writes in the book’s afterword: “If On the Origin of Species was biology’s deadliest blow to supernaturalism, we may come to see A Universe From Nothing as the equivalent from cosmology.”

Just to be clear: Dawkins is comparing Lawrence Krauss to Charles Darwin. Why would Dawkins say something so foolish? Because he hates religion so much that it impairs his scientific judgment. He succumbs to what you might call “The Science Delusion.” [Continue reading…]

Whatever you think, you don’t necessarily know your own mind

Keith Frankish writes: Do you think racial stereotypes are false? Are you sure? I’m not asking if you’re sure whether or not the stereotypes are false, but if you’re sure whether or not you think that they are. That might seem like a strange question. We all know what we think, don’t we?

Most philosophers of mind would agree, holding that we have privileged access to our own thoughts, which is largely immune from error. Some argue that we have a faculty of ‘inner sense’, which monitors the mind just as the outer senses monitor the world. There have been exceptions, however. The mid-20th-century behaviourist philosopher Gilbert Ryle held that we learn about our own minds, not by inner sense, but by observing our own behaviour, and that friends might know our minds better than we do. (Hence the joke: two behaviourists have just had sex and one turns to the other and says: ‘That was great for you, darling. How was it for me?’) And the contemporary philosopher Peter Carruthers proposes a similar view (though for different reasons), arguing that our beliefs about our own thoughts and decisions are the product of self-interpretation and are often mistaken.

Evidence for this comes from experimental work in social psychology. It is well established that people sometimes think they have beliefs that they don’t really have. For example, if offered a choice between several identical items, people tend to choose the one on the right. But when asked why they chose it, they confabulate a reason, saying they thought the item was a nicer colour or better quality. Similarly, if a person performs an action in response to an earlier (and now forgotten) hypnotic suggestion, they will confabulate a reason for performing it. What seems to be happening is that the subjects engage in unconscious self-interpretation. They don’t know the real explanation of their action (a bias towards the right, hypnotic suggestion), so they infer some plausible reason and ascribe it to themselves. They are not aware that they are interpreting, however, and make their reports as if they were directly aware of their reasons. [Continue reading…]

Eagles take down drones

The New York Times reports: Its wings beating against a gathering breeze, the eagle moves gracefully through a cloudy sky, then swoops, talons outstretched, on its prey below.

The target, however, is not another bird but a small drone, and when the eagle connects, there is a metallic clunk. With the device in its grasp, the bird of prey returns to the ground.

At a disused military airfield in the Netherlands, hunting birds like the eagle are being trained to harness their instincts to help combat the security threats stemming from the proliferation of drones.

The birds of prey learn to intercept small, off-the-shelf drones — unmanned aerial vehicles — of the type that can pose risks to aircraft, drop contraband into jails, conduct surveillance or fly dangerously over public events.

The thought of terrorists using drones haunts security officials in Europe and elsewhere, and among those who watched the demonstration at Valkenburg Naval Air Base this month was Mark Wiebes, a detective chief superintendent in the Dutch police.

Mr. Wiebes described the tests as “very promising,” and said that, subject to a final assessment, birds of prey were likely to be deployed soon in the Netherlands, along with other measures to counter drones. The Metropolitan Police Service in London is also considering using trained birds to fight drones. [Continue reading…]

This has been described as a “a low-tech solution for a high-tech problem” but, on the contrary, what it highlights is the fact that in terms of maneuverability, the flying skills of an eagle (and most other flying creatures) are vastly superior to any form of technology.

In this, as in so many other instances, technology crudely imitates nature.

Here ‘lies’ Aristotle, archaeologist declares — and this is why we should care

Amy Ellis Nutt writes: For starters, he is the father of Western science and Western philosophy. He invented formal logic and the scientific method and wrote the first books about biology, physics, astronomy and psychology. Freedom and democracy, justice and equality, the importance of a middle class and the dangers of credit — they’re just a sampling of Aristotle’s political and economic principles. And, yes, Christianity, Islam and our Founding Fathers also owe him a lot.

Nearly 2-1/2 millennia after Aristotle’s birth, we now know where his ashes most likely were laid to rest: in the city of his birth, Stagira, on a small, picturesque peninsula in northern Greece.

“We have no [concrete] evidence, but very strong indications reaching almost to certainty,” archaeologist Kostas Sismanidis said through a translator at this week’s World Congress celebrating “Aristotle 2400 Years.” [Continue reading…]

The void of the float tank stops time, strips ego and unleashes the mind

M M Owen writes: The floatation tank was invented in 1954. Amid debates over whether consciousness was a purely reactive phenomenon or generated by resources of its own making in the mind, the neuroscientist John Lilly arrived at a novel way to examine the problem: isola te the mind from all sources of external stimulation, and see how it behaved. Serendipitously, Lilly’s place of work, the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, possessed a sealed, soundproof tank, built during the Second World War to facilitate Navy experiments on the metabolisms of deep-sea divers. The first floatation tank was born. It resembled a large upright coffin, in which the floater was suspended in water, head engulfed in a rubber breathing mask. Despite this grim setup, during his floats Lilly perceived that the mind was far from merely reactive, and that ‘many, many states of consciousness’ emerged from total isolation. He was hooked.

Lilly was the sort of scientist it’s hard to imagine rising to prominence today. Alongside inventing the first floatation tank, he was an evangelist of psychedelics fascinated by human-dolphin communication and convinced that a council of invisible cosmic entities governed reality. Despite a mixed reputation among his scientific peers, Lilly’s almost single-handed promotion of floating in the 1960s caused it to catch on. In 1972, the computer programmer Glenn Perry attended one of Lilly’s floating workshops, and was so taken with the tank experience that, over the following year, he designed the first inexpensive tanks for home use. To this day, his so-called ‘Samadhi’ tanks (after the ultimate stage in meditation) remain among the most popular, with retail prices starting at around $11,000.

Cultural notables such as the polymath Gregory Bateson and the self-help guru Werner Erhard visited Lilly’s Malibu home and tried out his tank. Word spread. In 1979, Perry opened the first commercial float centre in Beverly Hills.[Continue reading…]