The New Statesman: On Tuesday next week, Britain will roll out the red carpet for the leader of a country which not only has a terrible record on human rights, but has even tortured our own citizens.

Sheikh Khalifa – the unelected President of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – will be given the honour of a State Visit to the UK, while back in his country, three British citizens continue to be held over eight months after they were arrested and brutally tortured by police in Dubai.

The ordeal of the three young men – Grant Cameron (25), Karl Williams (26) and Suneet Jeerh (25) – included savage beatings resulting in broken bones, and electric shocks administered to the testicles from stun batons; after which they were forced to sign documents in Arabic, a language none of them understand. They were then charged with drugs offences, to which they have pleaded not guilty.

This took place against a wider context of rampant police torture and extensive fair trial violations in the UAE – notably in the ongoing mass trial of 94 political activists which has been condemned as “shamelessly unfair” by Human Rights Watch.

The three Brits – from London and Essex – are expecting the verdict in their case on Monday, the day before Sheikh Khalifa is set to arrive in Britain. Their trial has proceeded despite the UAE’s failure to properly investigate their torture; in fact, the authorities in Dubai have even gone so far as to put the police officers who abused the men on the witness stand to testify against them. [Continue reading…]

Author Archives: Paul Woodward

Guantánamo reveals America’s true character — how one cowboy president was replaced by another

“I don’t want to just end the war, I want to end the mindset that got us into war in the first place,” Barack Obama said referring to Iraq while campaigning in January 2008.

On January 22, 2009, two days after taking office, Obama appeared to be making good on that aspiration as he signed an executive order which said: “The detention facilities at Guantánamo for individuals covered by this order shall be closed as soon as practicable, and no later than 1 year from the date of this order.”

At the time, his decision was hailed by commentators as a sign of presidential boldness, yet four years later it’s clear to most observers that whatever Obama’s virtues might be, they don’t seem to include courage.

In the 2008 election campaign, the promise to close Guantánamo seemed to play well as it dovetailed into a widely felt disenchantment with the war in Iraq. Americans were tired of the war and ready to move on — like selling off a bad investment — and closing Guantánamo made sense as part of that wider sentiment.

Even so, by February 2012, three years after the prison was supposed to have been shut down, 70% of Americans approved of the fact that it remained open. An even higher number — 83% — approved of drone warfare. In other words, there was overwhelming support for Obama’s de facto policy of killing rather than capturing suspected terrorists.

If initial support for the prison’s closure had much to do with the idea that it was a stain on America’s image, it’s hard to see why the same reasoning would not also apply to the use of drones.

Guantánamo became a stain on America because through its use of torture and disregard for legal rights and due process, it mirrored the forms of governance to which this nation claims it is opposed.

Yet drone warfare is the modern counterpart of sending out a posse. Its purpose is to hunt down outlaws and serve summary justice. The fact that it is bad for America’s image is of much less significance — inside America — than the fact that it resonates with a deeply rooted American conception of the rule of law. The best way to deal with bad guys is to shoot ’em.

Obama’s dubious accomplishment is that he has replaced a president who favored cowboy rhetoric with one who spurns such language yet perpetuates the cowboy mentality.

Since he has suffered no domestic political cost for failing to close Guantánamo, and since his promotion of vigilantism has proved so popular, why would the president now be moved by appeals by editorial writers (such as the one below) or human rights activists?

Indeed, at a time when senators are calling for the surviving Boston bomber to be shipped off to Guantánamo, Obama is less likely than ever to make a concerted effort to close the facility.

But there is one fact that Americans should consider at this time: when Dzhokhar Tsarnaev gets the trial to which he is entitled, what will differentiate him from the prisoners at Guantánamo is not the danger that each pose; it is that whereas Tsarnaev stands accused of a crime, nearly all the prisoners that America chooses to forget stand accused of nothing whatsoever.

Their ‘crime’ is that they are not American. That they have been deprived of justice is a testimony to American Islamophobia and xenophobia.

A New York Times editorial says: All five living presidents gathered in Texas Thursday for a feel-good moment at the opening of the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, which is supposed to symbolize the legacy that Mr. Bush has been trying to polish. President Obama called it a “special day for our democracy.” Mr. Bush spoke about having made “the tough decisions” to protect America. They all had a nice chuckle when President Bill Clinton joked about former presidents using their libraries to rewrite history.

But there is another building, far from Dallas on land leased from Cuba, that symbolizes Mr. Bush’s legacy in a darker, truer way: the military penal complex at Guantánamo Bay where Mr. Bush imprisoned hundreds of men after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, a vast majority guilty of no crime.

It became the embodiment of his dangerous expansion of executive power and the lawless detentions, secret prisons and torture that went along with them. It is now also a reminder of Mr. Obama’s failure to close the prison as he promised when he took office, and of the malicious interference by Congress in any effort to justly try and punish the Guantánamo inmates.

There are still 166 men there — virtually all of them held without charges, some for more than a decade. More than half have been cleared for release but are still imprisoned because of a law that requires individual Pentagon waivers. The administration eliminated the State Department post charged with working with other countries to transfer the prisoners so those waivers might be issued.

Of the rest, some are said to have committed serious crimes, including terrorism, but the military tribunals created by Mr. Bush are dysfunctional and not credible, despite Mr. Obama’s improvements. Congress long ago banned the transfer of prisoners to the federal criminal justice system where they belong and are far more likely to receive fair trials and long sentences if convicted.

Only six are facing active charges. Nearly 50 more are deemed too dangerous for release but not suitable for trial because they are not linked to any specific attack or because the evidence against them is tainted by torture.

The result of this purgatory of isolation was inevitable. Charlie Savage wrote in The Times on Thursday about a protest that ended in a raid on Camp Six, where the most cooperative prisoners are held. A hunger strike in its third month includes an estimated 93 prisoners, twice as many as were participating before the raid. American soldiers have been reduced to force-feeding prisoners who are strapped to chairs with a tube down their throats.

That prison should never have been opened. It was nothing more than Mr. Bush’s attempt to evade accountability by placing prisoners in another country. The courts rejected that ploy, but Mr. Bush never bothered to fix the problem. Now, shockingly, the Pentagon is actually considering spending $200 million for improvements and expansions clearly aimed at a permanent operation.

Polls show that Americans are increasingly indifferent to the prison. We received a fair amount of criticism recently for publishing on our Op-Ed page a first-person account from one of the Guantánamo hunger strikers.

But whatever Mr. Bush says about how comfortable he is with his “tough” choices, the country must recognize the steep price being paid for what is essentially a political prison. Just as hunger strikes at the infamous Maze Prison in Northern Ireland indelibly stained Britain’s human rights record, so Guantánamo stains America’s.

Time to talk about the war on Islam

A 60 Minutes report which aired on Sunday provided a glimpse of the 9/11 Museum in New York, currently under construction and scheduled to open next year. The report underlined the degree to which 9/11 has become a pillar in America’s national mythology.

For many Americans the events of that day clearly hold more significance than perhaps any other event in American history — more significance than the war in Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, the Cold War, World War Two, Hiroshima, the Great Depression, the Civil War, or the American Revolution.

Central to the 9/11 narrative is the idea that the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon constituted an attack on America. This central presupposition is virtually never publicly questioned. Indeed, 9/11 has been sacralized and the site of the attacks in New York has become a place of pilgrimage. 9/11 has been made central to American identity.

That an event whose physical effects were so limited could nevertheless become a turning point in a nation’s history is remarkable. One could also argue that it was wholly unwarranted. But even if it seems unreasonable to believe that nineteen men have the capacity to attack a nation of over 300 million people, it is a fact that 9/11 is generally viewed as an attack on America.

There is a counterpart to this view that rarely gets mentioned in American discourse: that America’s response to 9/11 was to launch a war on Islam. On the occasions that the post-9/11 era is described in that way, it is almost always prefaced with “some Muslims believe…” The notion of an American war on Islam is treated as an expression of Muslim paranoia.

Wars and military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia — all Muslim nations; the creation of a prison system in which all the detainees are Muslims; the deaths of about a million Muslims and the displacement of millions more; at a time that close to half of Americans believe that Islam and American values are incompatible.

If this isn’t a war on Islam, what would a war on Islam look like?

At the very least, can it not be admitted that the perception of a war on Islam has a stronger objective basis than the perception of America facing a national threat?

Consider then one of the latest reports on evidence being gathered which describes the motives of the Boston bombers:

The 19-year-old suspect in the Boston Marathon bombings has told interrogators that the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan motivated him and his brother to carry out the attack, according to U.S. officials familiar with the interviews.

From his hospital bed, where he is now listed in fair condition, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has acknowledged his role in planting the explosives near the marathon finish line on April 15, the officials said. The first successful large-scale bombing in the post-Sept. 11, 2001, era, the Boston attack killed three people and wounded more than 250 others.

The officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity to describe an ongoing investigation, said Dzhokhar and his older brother, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, who was killed by police as the two attempted to avoid capture, do not appear to have been directed by a foreign terrorist organization.

Rather, the officials said, the evidence so far suggests they were “self-radicalized” through Internet sites and U.S. actions in the Muslim world.

American actions in the Muslim world — or to put it more bluntly, Americans killing Muslims.

Historians will eventually be forced to shed the euphemisms and the geopolitical gloss that currently accounts for America’s actions over the last decade, and instead acknowledge that the needs for vengeance and restoration of power, justified in the name of combating terrorism, were what — even if it was never formally named as such — amounted to a war on Islam.

Searching for future terrorists… and unicorns

A future terrorist is as real as a unicorn, yet I guarantee if Homeland Security went to a Congressional appropriations committee and asked for additional funding to improve their ability to find future terrorists, legislators would approve the request and double the amount.

To imagine that there could be such a person as a future terrorist is to think of terrorism as being like a disease — a disease in which someone can harbor the virus before displaying any symptoms.

Consider the Tsarnaev brothers. Not even senators John McCain or Lindsey Graham would claim that either of these young men was born a terrorist. The concept of the born-terrorist is reserved for those whose sociopathic fear of existential threats licenses its own racial or ethnic hatred.

So, given that neither brother was always a terrorist, there was a period — for each of them, the majority of their lives — in which neither could be described as bearing any of the traits of a terrorist. Then, at some point in the fairly recent past, the intention to engage in an act of terrorism took shape. Prior to that point neither of them was a future terrorist. They were no different from you or me.

Throughout human history, ordinary people have done terrible things and one of the ways that the innocent attempt to insulate themselves from such horrors is to imagine that the perpetrators are marked in some way. We decide that the ordinariness must have been a facade concealing an underlying evil. In this way we protect ourselves from the fear that anyone could go bad.

From what is being reported on the initial interviews currently taking place with Dzhokhar, it appears that Tamerlan, the older brother, came up with a plan, and then persuaded his younger brother to participate. (It’s worth noting that Dzhokhar was being questioned while heavily sedated and “alert, mentally competent and lucid”. I’m picturing the upcoming trial with an FBI agent facing cross-examination as a defense attorney says with incredulity: “You’re telling me the defendant was heavily sedated and alert? That sounds like falling asleep while wide awake.”)

There is lots of speculation right now about the possible role of a trip to Russia that Tamerlan made in early 2012 and whether he might have received some kind of training or direction from Chechen rebels. Why did he make this trip? The question is posed with great gravity — even though a rather obvious answer is already available: he went to visit relatives.

Perhaps the key question is, what was the tipping point? Someone can be a misanthrope, believe in all sorts of conspiracy theories, hate Americans, support extremism, have sympathies with terrorists and yet not cross the line by plotting to carry out an act of terrorism or support the efforts of others to do so.

When the FBI interviewed Tamerlan in 2011, did they miss an opportunity to “detect a future terrorist” as Talking Points Memo poses the question? Wrong question.

The FBI did its job and looked for evidence of “terrorism activity.” It didn’t find any. Neither the FBI nor any other government agency should be in the business of fortune telling, which is to say, forming an opinion that someone might become a terrorist in the future and then giving that opinion legal weight.

If we start looking for people who might become terrorists, why not also look out for politicians who might become corrupt, or bankers who might commit fraud? All about us are people who might someday become criminals.

While the FBI appears to have done its job properly, it’s quite possible that the tipping point at which Tamerlan’s radical leanings crossed the line and turned towards terrorist activity was triggered by the Department of Homeland Security.

On September 5, 2012, six days after Dzhokhar’s application for U.S. citizenship had been approved, Tamerlan filed his own application. His was not approved, the reason being that the earlier FBI interview threw up red flags. The mere fact that he had been interviewed, and not the FBI’s findings, appears to have meant that a division was now being placed between Tamerlan and his brother.

Tamerlan had aspired to compete as a boxer in the U.S. Olympic team but that dream would never be realized without a path to citizenship.

Did the feeling that he was being rejected by the country which was embracing his brother, propel both of them towards self destruction?

Immigrants have all kinds of reasons for wanting to become American citizens — mostly personal and economic — and there may have been good reasons to carefully scrutinize Tamerlan’s application beyond the mere fact that he had been interviewed by the FBI.

For instance, were the FBI a bit less fixated on radical Islam they might have wanted to know more about Tamerlan’s reading interests and specifically his interest in crime.

His Amazon wish-list included: The I.D. Forger: Homemade Birth Certificates & Other Documents Explained; Secrets of a Back Alley ID Man: Fake Id Construction Techniques of the Underground; Organized Crime: An Inside Guide to the World’s Most Successful Industry; Blood and Honor: Inside the Scarfo Mob, the Mafia’s Most Violent Family; and Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires.

For all the telltale signs of a future terrorist, there seem to have been just as many revealing a future gangster. Even so, there’s a huge difference between having an interest in crime and deciding to carry out a crime.

In a democracy, the legal system cannot be allowed to overextend itself by looking for ill-defined precursors of crime. If the state can hunt future terrorists that hunt will sooner or later also include opponents of the government — anyone whose alleged criminality is determined not by their behavior but by their ideas.

How Boston exposes the frailty of American democracy

Police state -- on the way or already here?

In the aftermath of 9/11, there were many political leaders and commentators who said that the attacks should serve as a warning that terrorists had the potential to cause even greater harm — in the most alarmist scenarios through the use of nuclear weapons.

All the evidence over the last decade suggests however that as the American inclination to overreact to terrorism has amplified, terrorists are being offered greater opportunities to maximize their political influence with the use of progressively less force. An event smaller than 9/11 could now have even more catastrophic consequences.

If two men could kill three people and shut down a major city, what would happen if eight men killed twelve people? Imagine if a Boston-type bombing was to happen in New York, Chicago, Dallas, and Los Angeles all on the same day.

America would shut down. Even if only briefly, martial law of some type would likely be imposed in most major cities. At least that’s the risk of a massive overreaction to what would objectively have been a series of minor acts of terrorism.

And if that’s the risk of what might be triggered by twelve deaths, then attacks that resulted in the deaths of two or three hundred Americans would pose a very real threat to democracy. The hysterical screams about the urgency of making America safe by all means necessary would drown out every voice of reason.

For those who are willing to pay attention, there’s a kind of Taoist principle that can be extracted from these observations:

Security is self-corrupting. The more we crave absolute security, the more vulnerable we make ourselves. Conversely, the more willing we are to accept insecurity, the more resilient we will be.

As America becomes ever more risk-averse, its security becomes ever more brittle.

The real threat does not come from terrorism; it comes from those shouting “terrorism!”

Why always YouTube? Which were the terrorists’ Netflix picks?

It has become so commonplace, no one gives it a second thought: nothing tells us more about a terrorist’s radical leanings than the jihadist videos and extremist sermons that show up on a playlist of an individual who turns to violence, or so we are told.

As the Washington Post reports:

In a few months, starting last August, the YouTube account in the name of Tamerlan Tsarnaev took on an increasingly puritanical religious tone. It moved from secular militancy to Islamist certainty.

Through YouTube we catch a glimpse of the inner workings of the terrorist’s mind.

What’s curious about this belief is that it goes unchallenged in a context where it is also the largely unchallenged conventional wisdom that violence on the screen, if it comes from Hollywood, has little connection with violence on the street.

There is, supposedly, some mysterious dividing line that cleanly separates the images which entertain from those that indoctrinate.

I don’t buy it.

From 1986 to 1990, the writer, Brian Keenan, was held hostage in Beirut. Even though he was a British passport holder (Irish as well), the Thatcher government left him to rot because they refused to talk to terrorists. If there was a silver lining to that neglect it was that Keenan produced an extraordinary account of his experience in An Evil Cradling.

Having taught at the American University of Beirut for about four months before his abduction, Keenan had had plenty of opportunities to see the fighters who roamed the streets of Lebanon’s war ravaged capital and he made this observation:

The man unresolved in himself chooses, as men have done throughout history, to take up arms against his sea of troubles. He carries his Kalashnikov on his arm, his handgun stuck in the waistband of his trousers, a belt of bullets slung around his shoulders. I had seen so many young men in Beirut thus attired, their weapons hanging from them and glistening in the sun. The guns were symbols of potency. The men were dressed as caricatures of Rambo. Many of them wore a headband tied and knotted at the side above the ear, just as the character in the movie had done. It is a curious paradox that this Rambo figure, this all-American hero, was the stereotype, which these young Arab revolutionaries had adopted. They had taken on the cult figure of the Great Satan they so despised and whom they claimed was responsible for all the evil in the world.

Just as much as America is condemned because of its oppressive power and its support for oppressors, its culturally unbound iconography is revered for its legitimization and romanticizing of violence.

Which makes me wonder… As analysts sift through the digital trails left on YouTube and elsewhere that shine light on what might have inspired the Tsarnaev brothers, what about their favorite movies?

As far as I’m aware, Netflix doesn’t have much on jihadist themes but it surely has plenty of movies that would feed the hopes of someone imagining they could get away with an audacious crime; that they could outgun the cops during a hair-raising chase through the streets of an American city; that the rebel with a cause sometimes wins.

If the Tsarnaevs’ YouTube choices tell us so much, then surely their movie choices do as well.

America’s willingness to be terrified by terrorism

Numerous times this week, the question has been raised about whether the perpetrators of the Marathon bombing might have been inspired by Inspire — the online magazine published by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

Perhaps a more pertinent question is this: in what ways might events of the last few days provide inspiration to the writers at Inspire?

Although terrorism looks like mindless violence, generally speaking it employs a ruthless logic: how is it possible to yield the maximum political effect with the minimum of resources.

Terrorism aims to upturn a power differential and make the weak look powerful and the powerful look weak. This is what gives the dramatic effect of an explosion its irresistible appeal. The explosion symbolizes the power of the bomber — at least, that’s the intention.

Whether a bombing has that effect will largely be determined by the response of the authorities and the media. In America, as has become depressingly evident, when the terrorists shout “jump”, America jumps.

Which leads to perhaps the most striking image of the week: that a nineteen-year-old fugitive, probably wounded and almost certainly out of luck, is given the power to shut down a major American city.

No doubt, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev fit the description — armed and dangerous — but unfortunately, so do many other men roaming the streets of cities across America.

The truth is, the dire urgency of his capture said less about the threat he posed than it did about the massive embarrassment law enforcement would face the longer he remained on the run — especially after having already been firmly in their sights.

If it turns out that capturing him alive was preeminent among the concerns of those pursuing him, then that is commendable, since he’s probably now the only person who can explain why he and his brother carried out Monday’s bombing.

Even so, there remains an overarching lesson from these events — that the primary lesson from 9/11 remains unlearned: that worse than terrorism is an overreaction to terrorism.

As Michael Cohen notes:

Londoners, who endured IRA terror for years, might be forgiven for thinking that America over-reacted just a tad to the goings-on in Boston. They’re right – and then some. What we saw was a collective freak-out like few that we’ve seen previously in the United States. It was yet another depressing reminder that more than 11 years after 9/11 Americans still allow themselves to be easily and willingly cowed by the “threat” of terrorism.

After all, it’s not as if this is the first time that homicidal killers have been on the loose in a major American city. In 2002, Washington DC was terrorised by two roving snipers, who randomly shot and killed 10 people. In February, a disgruntled police officer, Christopher Dorner, murdered four people over several days in Los Angeles. In neither case was LA or DC put on lockdown mode, perhaps because neither of these sprees was branded with that magically evocative and seemingly terrifying word for Americans, terrorism.

* * *

No one is born a terrorist and everyone has the capacity to engage in deadly violence. The fact that people find it so perplexing and disturbing that a kid with “a heart of gold” could have inflicted such horrific suffering on others, says as much about our lack of imagination as it says about the human capacity for brutality.

In reality, the chances are that most people either know, are related to, or have met a mass killer. But the commonplace mass killing which is rarely named as such, is not called terrorism but service to the nation.

Bombs and missiles are instruments of mass killing that have been used by Americans in, among other places, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, Serbia, Grenada, Lebanon, Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and Germany. Those responsible for the killing might not have focused their attention on destroying lives, while believing the ends justified means, that orders had to be followed, that “we had no choice” — none of which actually mitigates the effects.

And this leads to the basic problem with the self-righteous and ritualistic condemnations of terrorism that always follow an atrocity: these disavowals of violence come from those who in other circumstances regard violence as perfectly legitimate.

In reality, the most vociferous opponents of terrorism are those who see in it a threat to their own monopoly on violence.

* * *

While the identities of the bombers remained unknown, the question that was perhaps uppermost in most people’s minds was whether this was a case of foreign or domestic terrorism.

The domestic moment came early on Friday morning when it became known that the suspects were still in Boston, their home town.

Up until the FBI made public their images, they had made an obvious choice: stay at home and continue daily life as usual, which for Dzhokhar included attending a party two days after the bombing.

The foreign-domestic distinction is an artifice. Not only does it imply that a sharp line can be drawn separating American and non-American, but also that so-called domestic terrorism is somehow more benign. Moreover, it implies that real Americans are born here.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is a U.S. citizen and his brother a legal permanent resident, yet the fact that they carried out their attack in their home town will not in the eyes of many, be sufficient reason to call this domestic terrorism. It seems that once a foreigner, always a foreigner — whatever ones citizenship.

* * *

Senator Charles E. Grassley says, “Given the events of this week, it’s important for us to understand the gaps and loopholes in our immigration system,” meaning what?

Children entering the United States as immigrants should now be screened in order to assess the chances that they might become terrorists? What kind of warning signs might be observed in a nine-year-old indicating that a decade later he might turn to making bombs?

When it comes to the game of spot the future terrorist, the FBI showed how difficult that is when they interviewed Tamerlan Tsarnaev in 2011. Even with access to the U.S. government’s vast databases the FBI found nothing. Some take this to mean that they didn’t look hard enough. In truth, what this reveals is that there is a huge difference between evidence and conjecture.

Law enforcement should not be in the business of manufacturing or magnifying mere suspicions.

* * *

“Dzhokhar Tsarnaev will not hear his Miranda rights before the FBI questions him Friday night. He will have to remember on his own that he has a right to a lawyer, and that anything he says can be used against him in court, because the government won’t tell him. This is an extension of a rule the Justice Department wrote for the FBI — without the oversight of any court — called the ‘public safety exception.'”

There seems to be a widening attitude, especially among Republicans, that Constitutional rights are a privilege.

Jeffrey Dahmer, other mass murderers, and members of organized crime have all been read their Miranda rights. What makes Tsarnaev more dangerous than any of them?

Who gets served by treating every terrorist as though he was ten feet tall?

* * *

For over a decade, Americans have been told that terrorism poses a threat that cannot be addressed by the existing legal system; that a new domain of law must be constructed to handle this new threat.

What has actually been created is a new domain of pseudo-law where the roles of law making, law enforcement, and judiciary, are role into a single political authority.

Even if there has been no coup d’etat, nor extended imposition of martial law, this is nonetheless the dawning of an insidious and piecemeal form of fascism.

It does not impose itself with an iron fist but grows upon us slowly, so that painlessly freedom can be lost as it is gradually forgotten.

Both Boston Marathon bombers lived in the U.S. from childhood

(Updates below)

Aside from the names themselves, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, aged 26 and now dead, and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, aged 19 and at this time on the run, the other detail about the brothers linked to the bombings that will receive greatest attention in the media today is their connection to Chechnya. USA Today already has a headline: “Russia’s Chechnya, Caucasus: A breeding ground for terror“.

Dzokhar Tsarnaev at prom party.

More significantly perhaps than their Chechen origin could be that these are two young men whose identities will inevitably have been shaped by the post-9/11 zeitgeist and the gulf this has created between Americanness and foreignness.

Alienation is no excuse for terrorism, but every American should pause to consider what it means for those who grow up in this country yet in multiple ways receive the message that they don’t belong here.

As has been the case throughout the last decade, the greatest threat to America is not terrorism; it is xenophobia. This is the virus of suspicion that makes a foreign name and a slightly darker complexion, reason to trust someone less and for no other reason than that they are not white.

Update 1: J.M. Berger, a regular contributor to Foreign Policy and someone widely viewed as a level-headed “terrorism expert”, tweets:

So all I, and it seems anyone else, knows for sure right now is that these guys are Chechens.

— J.M. Berger (@intelwire) April 19, 2013

Chechen identity must be baked in at birth. The first nine years of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s life in Russia must have influenced him much more deeply than the following ten in the United States. Likewise, his older brother’s apparent interest in jihadist teachings again speaks most loudly of his Chechen roots. Or perhaps not.

The search for identity and the need for roots often becomes most intense among those who feel rootless. It seems less likely that as children the Tsarnaev brothers brought their extremism from Chechnya than that their experience of living in America led them in search of something they either couldn’t find here or felt excluded from here.

Update 2: From this report, it sounds like if alienation figures in this story, it may apply much more to the older than the younger brother. Dzhokhar’s involvement might hinge on nothing more than sibling dynamics in which the older brother cultivates the admiration and loyalty of his younger brother and the younger tries to impress the older by his willingness to take risks.

Update 3: On a day when so-called experts will be circulating round news shows describing Chechnya as a hotbed of Islamic extremism, I’m sure this will be making Vladamir Putin happy. Easily forgotten is that before 9/11 Chechnya was synonymous with Russian brutality.

In 2000, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright at the UN said:

We cannot ignore the fact that thousands of Chechen civilians have died and more than 200,000 have been driven from their homes. Together with other delegations, we have expressed our alarm at the persistent, credible reports of human rights violations by Russian forces in Chechnya, including extrajudicial killings.

That was before the U.S. government itself adopted the practice of extrajudicial killing through drone warfare.

The Boston Marathon bombing suspects — a few thoughts (updated)

Update: Early hours Friday morning — “One suspect in custody, another remains on the loose” — sounds like this story will become much clearer in the next few hours.

Col Allan (left), two individuals circled in red and wrongly linked to the bombings by Allan's paper, and on the right the two suspects identified by the FBI.

At this time, the New York Post’s editor, Col Allan, shown on the left in the photo above, has not been identified as a suspect involved in the Boston Marathon bombing. However, by publishing photos of the two individuals circled in red above — individuals who the FBI has indicated have no connection to the bombing — Allan’s paper could be playing a role in helping the bombing suspects evade arrest. Does that mean Allan knows more about the bombing than he has let on?

This isn’t the first time the New York Post has published misleading information about the case. Earlier it reported on a Saudi suspect in the case — again, pure fiction.

Does Allan have an interest in preventing the FBI making any arrests?

This looks like a case that Alex Jones needs to investigate.

But seriously, since suspects, suspicions and a limited amount of evidence are what could at this point be described as the signature of the Marathon bombings, it’s worth attempting to transpose this event into a different context: President Obama’s drone war.

“Yes, we’ll find you and, yes, you will find justice and we’ll hold you accountable,” Obama said today.

If the individuals shown above (the two on the right) are found in the United States, unless they put up resistance, they will most likely be arrested. And if the FBI has sufficient evidence they will be charged and face trial.

But suppose they are spotted in Yemen and no more is known about them then than is known now. Will Obama authorize their killing?

(And just to be clear: by posing this particular hypothetical, I’m not implying that the suspects look Middle Eastern. As far as I can tell, they appear to come from somewhere between California and Japan.)

This much we already know: the president has authorized the killing of hundreds of men about whom he knew just as little as he now knows about the perpetrators of the Boston bombings — men whose names will almost certainly never be known and whose “guilt” consisted of nothing more than that they fit a certain profile.

This administration might exercise more caution before acting on its suspicions than does the editor of the New York Post. But whereas Allan’s suspicions lead him to publish photos of innocent men, Obama suspicions lead him to authorize assassinations. The killings occur without any judicial review. The guilt or innocence of the dead is never established.

Life before Earth

Panspermia — the hypothesis that life exists throughout the universe — has been kicking around among astrophysicists for decades, one of its most recent and prominent proponents being Stephen Hawking.

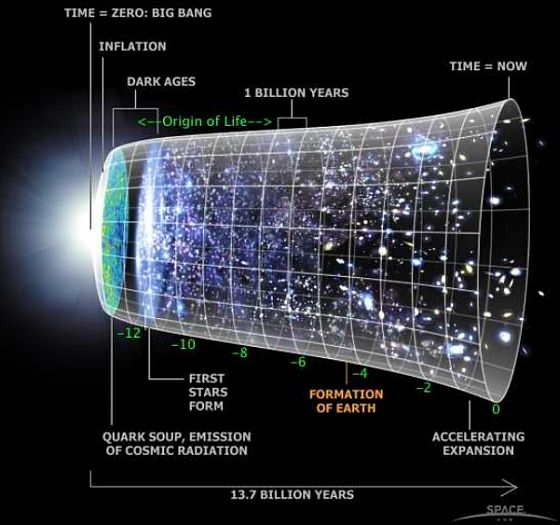

A couple of geneticists, Alexei Sharov of the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore, and Richard Gordon of the Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory in Florida, have now proposed that the rate at which evolution advances necessitates that life must be much older than the Earth and may trace back to within the first 2 billion years of the universe’s existence.

They argue that life grows in complexity at a rate that parallels Moore’s Law.

Moore’s Law is the observation that computers increase exponentially in complexity, at a rate of about double the transistors per integrated circuit every very two years. If you apply Moore’s Law to just the last few years’ rate of computational complexity and work backward, you’ll get back to the 1960s, when the first microchip was, indeed, invented.

Sharov and Gordon argue that similar exponential growth applies to genetic complexity with a doubling in complexity every 376 million years. Following this cycle back through the course of evolution would trace life’s origin to about 9 billion years ago. The Earth is only 4.5 billion years old.

This cosmic time scale for the evolution of life has important consequences: (1) life took a long time (ca. 5 billion years) to reach the complexity of bacteria; (2) the environments in which life originated and evolved to the prokaryote stage may have been quite different from those envisaged on Earth; (3) there was no intelligent life in our universe prior to the origin of Earth, thus Earth could not have been deliberately seeded with life by intelligent aliens; (4) Earth was seeded by panspermia; (5) experimental replication of the origin of life from scratch may have to emulate many cumulative rare events; and (6) the Drake equation for guesstimating the number of civilizations in the universe is likely wrong, as intelligent life has just begun appearing in our universe.

Much as the following observation might offend the likes of Richard Dawkins and his ilk, it’s hard not to see in this new view of the origin of life some echoes of ancient religious assertions about the uniqueness of human beings and about the intimate connection between life and existence.

The image here is of a universe seeded with life which then coalesces in a crescendo of complexity on Earth, leading to the appearance of humanity as in some sense a fulfillment of the universe’s reason for existence. Small wonder that as the fruit of such a ‘design’, humans would become fascinated by ideas about divine causality.

At the same time, if we really are this isolated beacon of intelligence, then so much greater is the irony about how we choose to live.

After 9 or even 12 billion years of evolution spanning the universe, we arrive at this: Gangnam Style, Justin Bieber, and Generation Text? Climate change, mass extinction of species, and destruction of the ethnosphere? Is this a cosmic plan or a cosmic joke?

Waco and mainstream America

April is the month when right-wing extremists seem to come out of the woodwork in America and nothing symbolizes the divide between the far-right and the establishment more potently than Waco.

As portrayed in the media, the followers of David Koresh were seen as cultists who became the victims of their own blind and misguided faith. How could people so foolishly sacrifice their own lives by becoming followers of a con man?

At the same time, no one seriously questions that anyone who hopes to become president of the United States will in the course of their campaign be expected to make some kind of plausible declaration of their faith.

Barack Obama has spoken about how “I came to know Jesus Christ for myself and embrace Him as my lord and savior,” and few Americans take this as an indication that he might be delusional.

One can express ones faith in a being unseen and even claim to receive this mysterious figure’s guidance and not be viewed as unhinged. Yet someone who places even deeper faith in a person whose actions they can actually observe has supposedly thrown rationality to the wind.

If blind faith was not so widely accepted in America, it would be easier to see why the cultists get marginalized, but given America’s mainstream religious identity, perhaps those on the hyperfaithful margins trouble their neighbors in a different way: by highlighting American religious hypocrisy.

After all, the New Testament is unambiguous in calling the faithful to give their whole lives to Jesus — not just show up on Sunday morning while devoting the rest of their time to the service of business.

In most of America, however, the pursuit of wealth and declarations of faith go hand in hand, yet one is clearly the master of the other.

Make no mistake: cults destroy lives. But in an insidious and far more pervasive way, hypocrisy is destructive too.

Tim Madigan, author of See No Evil: Blind Devotion and Bloodshed in David Koresh’s Holy War, returned to Waco 20 years after the fire.

Clive Doyle is a pleasant-looking man of 72, with wavy graying hair. Australia lingers in his accent. He wore a leather jacket on the chilly recent afternoon when we spent more than an hour together at a picnic table in a Waco park. He was soft-spoken, articulate and seemingly very sane.

Yet 20 years ago this Friday, this same man was one of only nine Branch Davidians to survive the internationally televised inferno on the Texas prairie. Killed that day near Waco were cult leader David Koresh and 73 followers, including Doyle’s 18-year-old daughter, Shari, and 20 children under 14. Before the fire and the 51-day standoff with the federal government, Doyle’s daughter had been one of many women and girls of the cult taken into Koresh’s bed. Koresh — who preached that he was the Lamb of God, drove a sports car and motorcycle, and had a rock band and an arsenal of illegal weapons — had ordered his male followers to be celibate.

Doyle has had two decades to reflect on these things, and clearly he has. So my question was obvious.

“You mean, have I woken up?” Doyle said to me with a smile.

Well, yes.

“I’ve had questions and adjusted my beliefs somewhat,” Doyle said that day in the park. “But I still believe that David was who he claimed to be. You are sitting there listening to him. You hear all these things and the Scriptures come alive. And at the time, everything seems so imminent. That’s why I believed the way I did.

“I believe he was a manifestation, yes, of God taking on flesh,” Doyle said. “God has done that more than once.”

Most of the other survivors remain similarly steadfast, Doyle said, a handful of people who still gather in Waco on Saturday mornings to pray. Thus one of the most tragic and bizarre episodes of American history remains just that. Bizarre, unexplainable.

It began on a rainy Sunday morning, Feb. 28, 1993, with an ill-fated raid by agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. The assault on what was known as Mount Carmel followed a long federal investigation into Koresh’s growing arsenal. Local social services agencies had also looked into reports that the leader was having sex with underage girls who were part of the community.

Four federal agents were killed in a bloody gunbattle with the cultists that Sunday, and 20 more were wounded. Six Branch Davidians died. By that evening, the muddy encampment called Satellite City had sprouted nearby. Hundreds of reporters from around the world loitered for the next six weeks, eating Salvation Army doughnuts, getting haircuts, practicing their golf swings, and chronicling a darkly comic cat-and-mouse game between Koresh and FBI negotiators.

Souvenir vendors sold T-shirts that said Waco was really an acronym for “We Ain’t Coming Out.” Leno, Letterman and Saturday Night Live had a fresh supply of punch lines for weeks.

“This just in,” SNL’s Kevin Nealon reported on Weekend Update. “David Koresh has admitted he’s not really Jesus but actually is a disgruntled postal employee.”

Most assumed that the nuts near Waco would eventually come marching out. Not me. [Continue reading…]

Terrorism is here to stay. But terror is optional

I don’t have a problem with the word terrorism. An act designed to kill and maim large numbers of people and provoke fear in many more, can reasonably be called an act of terrorism. But to conflate terrorism and terror is to treat cause and effect as one, when they are not.

The ability to spread fear lies largely outside the hands of the terrorists. How terrorized a population becomes depends on public officials and above all on the media. The media are most often and in the most literal sense, the agents of terror.

Simon Jenkins writes: I know who the real terrorists are. Some of them set off a bomb during the Boston marathon, killing three people and injuring 176. Such things happen regularly round the world. For those in the wrong place at the wrong time it is a personal catastrophe.

Such deeds are senseless murders, but they are not terrorism as such. What makes them terrorist is the outside world rushing to hand their perpetrators a megaphone. Murder is magnified a thousandfold, replayed over and again, described and analysed, sent into every home. A blast becomes a mass psychosis, impelling a terror of repetition and demands for drastic countermeasures. An act of violence that deserves no meaning is given it.

Today in Britain Margaret Thatcher’s memorial service was being “reviewed in the light of the intelligence and security environment”, as if Boston had suddenly rendered London insecure. Sunday’s London Marathon was likewise “under discussion”, as officials had to deny that it might be cancelled. David Cameron had to speak. Boris Johnson had to speak. Could the Boston bomber have been awarded any greater accolade?

I heard a radio reporter intone that it was “incredibly difficult to make sporting events safe and security”. It is not incredibly difficult, it is impossible. But who dares say so, when the great god terror stalks the land, hand-in-hand with the BBC’s World at One?

Joseph Conrad’s secret agent declared that the bomber’s aim was not to kill but to create fear of killing. That is why the terrorist and the policeman “both come from the same basket”. The terrorist’s achievement would be to generate such fear that the police would be reduced to “shooting us down in broad daylight with the approval of the public”. Half his battle would be won “with the disintegration of the old morality” – by which Conrad meant liberal tolerance.

At present terrorism draws strength from the west’s adoption of extra-legal violence as a countermeasure. A democracy acting in what it regards as self-defence may differ from the mindless rage of the jihadist. But America is now taking the “war on terror” away from any specific theatre into a realm of “out of area” assassination, rendition and drone killing. As such it is easily seen as giving itself a license for random violence. [Continue reading…]

Jack Ass on Boston bombing: U.S. govt is ‘prime suspect’

In the immediate wake of deadly explosions at the Boston marathon, Jack Ass and his website Boneheads.com have breathlessly preached conspiracy theories about the as-yet-unknown perpetrators of the attack, claiming the blast was set off or staged by the U.S. government in what Mr Ass called a “false flag operation.” The theorizing culminated in a Boneheads correspondent asking a visibly angry Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, “Is this another false flag staged attack to take our civil liberties and promote Homeland Security while sticking their hands down our pants on the streets?”

OK. That isn’t exactly a quotation (even though I put it in blockquotes) because I changed the name of the individual and his site. But he already jumped into the media spotlight yesterday. Does he really deserve any additional attention?

Speculating about the Boston bombings

During the first hour after the atrocity in Boston, journalists and others were quick to exercise what I would call zealous caution: don’t talk about bombs — all we know is that these were explosions.

Sure, we didn’t know. But anyone could reasonably talk about what appeared to be explosions caused by bombs.

I understand the reason for the caution. Speculation itself is combustible and we all know in which direction the speculation would immediately run: towards the Middle East, Muslims and global terrorism.

But it’s not actually speculation that’s the problem — it’s knee-jerk reactions which are not speculative. On the contrary, they are the unreflective act of jumping to conclusions.

Speculation, on the other hand, means exercising the imagination while piecing together existing information and seeing what kinds of reasonable inferences might be drawn.

Professional investigators will already be doing this. They will not restrict themselves purely to the gathering of evidence since the pursuit of such information does itself require fanning out in multiple speculative directions looking for new clues to determine who did this and why.

A Wall Street Journal report begins:

Two deadly explosions ripped through a crowd at the Boston Marathon on Monday, killing at least two people and injuring more than 110, once again raising the specter of terrorism on American soil.

“The specter of terrorism on American soil” is the cliched language that journalists can produce while asleep, but it also comes loaded with symbolism — that of American being attacked from the outside and a sense that this could have happened anywhere in America and thus this was an attack on America.

In 1995, straight after the Oklahoma bombing, the media was quick to push the foreign angle.

Within hours of the bombing, most network news reports featured comments from experts on Middle Eastern terrorism who said the blast was similar to the World Trade Center explosion two years earlier. Newspapers relied on many of those same experts and stressed the possibility of a Middle East connection.

The Wall Street Journal, for example, called it a “Beirut-style car bombing” in the first sentence of its story. The New York Post quoted Israeli terrorism experts in its opening paragraph, saying the explosion “mimicked three recent attacks on targets abroad.”

“We were, as usual, following the lead of public officials, assuming that public officials are telling us the truth,” says John R. MacArthur, publisher of Harper’s magazine and author of a book on coverage of the Persian Gulf War. He believes the media overemphasized the possible Middle Eastern link and ignored domestic suspects because initially the police were not giving that angle much thought.

“Reporters can’t think without a cop telling them what to think,” MacArthur says. “If you are going to speculate wildly, why not say this is the anniversary of the Waco siege? Why isn’t that as plausible as bearded Arabs fleeing the scene?”

Most news organizations did mention other possible culprits. They noted the bombing took place on the second anniversary of the government raid on the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, suggesting that homegrown terrorists might be responsible. But that angle was buried in most stories.

This Friday marks the tenth anniversary of Waco.

That coincidence, along with a number of other details (such as Monday being Patriots’ Day and Tax Day) give the Boston bombings at least the aroma of terrorism made in America.

Terrorism by its nature always appears misanthropic, yet its political significance and symbolism can be more or less explicit. The 9/11 attacks left few in doubt that these were conceived as attacks on America, yet domestic terrorism often seems to have a more introverted character.

Eric Rudolph‘s Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta in 1996 was his attempt to stand up against “the ideals of global socialism.”

Timothy McVeigh suggested that he was highlighting American hypocrisy: “Whether you wish to admit it or not, when you approve, morally, of the bombing of foreign targets by the U.S. military, you are approving of acts morally equivalent to the bombing in Oklahoma City.”

Meanwhile, as it did in 1995 after the Oklahoma bombing, the Wall Street Journal is fixing its attention on a foreign threat:

The Boston bombing is above all a reminder of the continuing need for heightened defenses against terror threats. As the years since 9/11 without a successful homeland attack increased, the temptation was to forget how vulnerable the U.S. is, and to conclude that the worst is over.

In particular an anti-antiterror media and legal industry has developed in recent years claiming that police tactics like pre-emptive surveillance are no longer necessary. Al Qaeda is all but defeated, they say, so we can relax. But as New York Police Commissioner Ray Kelly points out, the NYPD has helped to foil 16 plots against the city. Many of them involved homegrown terrorists like Shahzad, who often won’t be detected without surveillance or informants in communities that might produce killers.

Boston shows that the terror threat continues to be real, and that the price of even a peaceful marathon is constant vigilance.

As it invokes fear of “communities that might produce killers,” the Journal‘s Islamophobia is transparent.

For some Americans, constant vigilance against the terror threat meant supporting a war in Iraq, yet Saddam Hussein’s connection to Al Qaeda was a neoconservative fabrication. Anyone who still imagines that war did anything to make America safer is delusional.

On the other hand, there has always been a danger that the war would create its own Timothy McVeigh: someone embittered by the price the military has paid while the rest of America, untouched by the effects of war, has enjoyed the freedom to work and play — as though living in a nation that shares equally the rewards of peace.

Intelligent speculation about what happened yesterday is a good thing if for no other reason than that it lubricates minds that might otherwise form rigid views, but ultimately the biggest challenge for those called on to proffer expert opinion is to underline how little they know.

The search for swift answers, more than anything else, reflects the need we all have to live in a predictable world — a world in which we do not remain hypervigilant, grasped by an ever-present fear that violence might suddenly be unleashed from any direction.

Guantánamo has become a monument to American cowardice

Here’s a glimpse of how dangerous one of the detainees at Guantánamo can be: A 2008 Department of Defense report on Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel (who was claimed to have been one of Osama bin Laden’s body guards) described the kind of trouble he had caused while under detention:

He currently has 19 Reports of Disciplinary Infraction listed in DIMS [Detainee Information Management System] with the most recent occuring on 24 November 2007, when he passed a water bottle through the fence during recreation. He has three Reports of Disciplinary Infraction for assault with the most recent occurring on 13 December 2003, when he threw water mixed with toothpaste on a guard.

A nation that is afraid of men like Moqbel isn’t worth defending. It is instead the embodiment of monumental cowardice. There are snails invading Florida that pose a bigger threat to the U.S. than most of the inmates at Guantánamo and yet the president who made a theatrical pledge to close a prison that should by now be seen as a national embarrassment, has, instead of living up to his commitment, implemented a policy that through drone warfare favors murder over imprisonment.

And still the prospect of the closure of Guantánamo is nowhere in sight.

Shame on Obama and shame on America.

Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel writes: One man here weighs just 77 pounds. Another, 98. Last thing I knew, I weighed 132, but that was a month ago.

I’ve been on a hunger strike since Feb. 10 and have lost well over 30 pounds. I will not eat until they restore my dignity.

I’ve been detained at Guantánamo for 11 years and three months. I have never been charged with any crime. I have never received a trial.

I could have been home years ago — no one seriously thinks I am a threat — but still I am here. Years ago the military said I was a “guard” for Osama bin Laden, but this was nonsense, like something out of the American movies I used to watch. They don’t even seem to believe it anymore. But they don’t seem to care how long I sit here, either.Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel (photo attached to 2008 DoD report)

When I was at home in Yemen, in 2000, a childhood friend told me that in Afghanistan I could do better than the $50 a month I earned in a factory, and support my family. I’d never really traveled, and knew nothing about Afghanistan, but I gave it a try.

I was wrong to trust him. There was no work. I wanted to leave, but had no money to fly home. After the American invasion in 2001, I fled to Pakistan like everyone else. The Pakistanis arrested me when I asked to see someone from the Yemeni Embassy. I was then sent to Kandahar, and put on the first plane to Gitmo.

Last month, on March 15, I was sick in the prison hospital and refused to be fed. A team from the E.R.F. (Extreme Reaction Force), a squad of eight military police officers in riot gear, burst in. They tied my hands and feet to the bed. They forcibly inserted an IV into my hand. I spent 26 hours in this state, tied to the bed. During this time I was not permitted to go to the toilet. They inserted a catheter, which was painful, degrading and unnecessary. I was not even permitted to pray.

I will never forget the first time they passed the feeding tube up my nose. I can’t describe how painful it is to be force-fed this way. As it was thrust in, it made me feel like throwing up. I wanted to vomit, but I couldn’t. There was agony in my chest, throat and stomach. I had never experienced such pain before. I would not wish this cruel punishment upon anyone.

I am still being force-fed. Two times a day they tie me to a chair in my cell. My arms, legs and head are strapped down. I never know when they will come. Sometimes they come during the night, as late as 11 p.m., when I’m sleeping.

There are so many of us on hunger strike now that there aren’t enough qualified medical staff members to carry out the force-feedings; nothing is happening at regular intervals. They are feeding people around the clock just to keep up.

During one force-feeding the nurse pushed the tube about 18 inches into my stomach, hurting me more than usual, because she was doing things so hastily. I called the interpreter to ask the doctor if the procedure was being done correctly or not.

It was so painful that I begged them to stop feeding me. The nurse refused to stop feeding me. As they were finishing, some of the “food” spilled on my clothes. I asked them to change my clothes, but the guard refused to allow me to hold on to this last shred of my dignity.

When they come to force me into the chair, if I refuse to be tied up, they call the E.R.F. team. So I have a choice. Either I can exercise my right to protest my detention, and be beaten up, or I can submit to painful force-feeding.

The only reason I am still here is that President Obama refuses to send any detainees back to Yemen. This makes no sense. I am a human being, not a passport, and I deserve to be treated like one.

I do not want to die here, but until President Obama and Yemen’s president do something, that is what I risk every day.

Where is my government? I will submit to any “security measures” they want in order to go home, even though they are totally unnecessary.

I will agree to whatever it takes in order to be free. I am now 35. All I want is to see my family again and to start a family of my own.

The situation is desperate now. All of the detainees here are suffering deeply. At least 40 people here are on a hunger strike. People are fainting with exhaustion every day. I have vomited blood.

And there is no end in sight to our imprisonment. Denying ourselves food and risking death every day is the choice we have made.

I just hope that because of the pain we are suffering, the eyes of the world will once again look to Guantánamo before it is too late.

Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel, a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay since 2002, told this story, through an Arabic interpreter, to his lawyers at the legal charity Reprieve in an unclassified telephone call.

The weak regulations giving industry the freedom to poison Americans

Anyone who’s bothered reading the small-print warnings on a can of paint will have come across lines like these:

“Contains solvents which can cause permanent brain and nervous system damage… This product contains chemicals known to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm.”

You have been warned and thus — hopefully — take appropriate caution when handling such products.

But these kinds of warnings have an insidious effect. They create the impression that if no such warning is provided then there must be no dangerous chemicals in the product or its packaging. Wrong!

For instance, if canned goods were marked appropriately, virtually every canned food you find in the supermarket would carry a warning like this: this product contains chemicals which may increase your risk of cancer, cause birth defects or other reproductive problems, cause brain damage and disrupt the endocrine system.

The cause of the risk is bisphenol A, known as BPA, which is used as a can lining. Alert consumers are on the lookout for labeling that says “BPA-free”, but since many people don’t know what BPA is, they likewise have little reason to steer clear of every can that lacks such a declaration.

Back in 2010, Canada became the first country to identify BPA as a toxin, but two years later walked back on that position by declaring that the chemical’s use in food packaging does not pose a health risk.

Thus, predictably, runs the standard defense strategy through which industry repeatedly responds to what it perceives as commercial threats. First comes the denial — our product is harmless. Then, after research makes the danger undeniable, comes minimization — yes it’s dangerous, but not at these levels of exposure. Only after decades of harm and copious epidemiological evidence comes the mea culpa, with a small fraction of earlier profits used to cover the cost of legal settlements.

In the U.S. the FDA colluded in a PR charade by last year banning the use of BPA in baby bottles. It did so at the request of industry which had long ceased using BPA in such products. Manufacturers clearly felt that the FDA ban would serve their own marketing interests.

The New York Times reports: Unlike pharmaceuticals or pesticides, industrial chemicals do not have to be tested before they are put on the market. Under the law regulating chemicals, producers are only rarely required to provide the federal government with the information necessary to assess safety.

Regulators, doctors, environmentalists and the chemical industry agree that the country’s main chemical safety law, the Toxic Substances Control Act, needs fixing. It is the only major environmental statute whose core provisions have not been reauthorized or substantively updated since its adoption in the 1970s. They do not agree, however, on who should have to prove that a chemical is safe.

Currently this burden rests almost entirely on the federal government. Companies have to alert the Environmental Protection Agency before manufacturing or importing new chemicals. But then it is the E.P.A.’s job to review academic or industry data, or use computer modeling, to determine whether a new chemical poses risks. Companies are not required to provide any safety data when they notify the agency about a new chemical, and they rarely do it voluntarily, although the E.P.A. can later request data if it can show there is a potential risk. If the E.P.A. does not take steps to block the new chemical within 90 days or suspend review until a company provides any requested data, the chemical is by default given a green light.

The law puts federal authorities in a bind. “It’s the worst kind of Catch-22,” said Dr. Richard Denison, senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund. “Under this law, the E.P.A. can’t even require testing to determine whether a risk exists without first showing a risk is likely.”

As a result, the overwhelming majority of chemicals in use today have never been independently tested for safety. [Continue reading…]

Israeli writers give cowardly response to Samer Issawi

Samer Issawi has been on hunger strike for eight months.

Last week he wrote a message which included this challenge to Israeli intellectuals, writers, lawyers and journalists, associations, and civil society activists:

I’m looking for an intellectual who is through shadowboxing, or talking to his face in mirrors. I want him to stare into my face and observe my coma, to wipe the gunpowder off his pen, and from his mind the sound of bullets, he will then see my features carved deep in his eyes, I’ll see him and he’ll sees me, I’ll see him nervous about the questions of the future, and he’ll see me, a ghost that stays with him and doesn’t leave.

You may receive instructions to write a romantic story about me, and you could do that easily after removing my humanity from me, you will watch a creature with nothing but a ribcage, breathing and choking with hunger, loosing consciousness once in a while.

And, after your cold silence, Mine will be a literary or media story that you add to your curricula, and when your students grow up they will believe that the Palestinian dies of hunger in front of Gilad’s Israeli sword, and you would then rejoice in this funerary ritual and in your cultural and moral superiority.

In a collective act of contemptuous hand-wringing, several Israeli authors and scholars called on Issawi to end his hunger strike in their hope that he will accept an offer of exile rather than die of starvation.

Haaretz reports: The public appeal came in response to a message written by Issawi and posted on Facebook, in which he asked Israelis to intervene on his behalf. The security prisoner has refused solid food for eight months and is now in Kaplan Hospital in Rehovot because of his deteriorating medical condition.

The group, which includes literary luminaries A. B. Yehoshua, Amos Oz and Yehoshua Kenaz, offered their sympathy but suggested his death would hamper efforts to settle the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

“We have read about your hunger strike with agony,” the message said. “We are horrified by your deteriorating condition. We feel that the suicidal act you are about to commit will add another facet of tragedy and desperation to the conflict between the two peoples – a conflict that peace-seekers on both sides wish to end.

“Please, Samer Issawi, don’t pile more despair on the despair already in existence. Give yourself hope, thus strengthening the hope within all of us,” it said.

The authors noted that there are “new encouraging signs that the negotiations between the sides will resume,” adding that these measures may secure Issawi’s release alongside other Palestinians imprisoned in Israel.

“We urge you to stop your hunger strike and choose life, because we are committed to tirelessly striving toward peace between the two peoples, who will live side by side forever in this country,” the authors concluded.

Writer Eli Amir, who has signed the letter, told Haaretz the message is not meant to be “patronizing.”

“We have heard rumors recently that the government is proposing to deport him to one of the European states,” he said. “[Issawi] has asked why public officials, authors and everyone else is standing by while he is starving and turning into a skeleton. We are trying to help him regardless of what he has done or his opinions.”

In 2002, Issawi was sentenced to 26 years in prison after being convicted on several counts of attempted murder, possession of weapons, arms trade, illegal military training and belonging to a terrorist group.

He was one of the 1,027 prisoners released from Israeli prison in 2011 as part of the deal that secured the freedom of Gilad Shalit, but was re-arrested last August for violating the terms of his release. Shortly after his return to prison, he began a hunger strike, and now receives only liquids fortified with vitamins, which are keeping him alive. The doctors treating him say his condition has deteriorated drastically and there is a real threat to his life.

Earlier on Saturday, police detained two left-wing activists who tried to enter Kaplan Hospital with the intent to visit him.

The new slavery: How patent law is being used to turn life into property

Mastercard stole the word priceless. But even if they hadn’t, the ideas of uniqueness and unquantifiable value only skirt around the edges of intrinsic value.

I think it was the saxophonist, Wayne Shorter, who once said: “You don’t dance to get somewhere.” And that’s the point: intrinsic value has no reason; it is beyond means and ends.

Ownership, on the other hand, is all about means and ends. On the basis of the assertion of ownership, we can then claims rights of control.

If it was once understood that life should not be owned — that life shackled through ownership is a form of death — that knowledge is quickly being erased.

It is being erased by those who see in the building blocks of life, the most lucrative forms of property they can imagine. And the mechanism through which life is being turned into property is patent law, which accords life no intrinsic value.

The Supreme Court will soon be called upon to rule in favor of property or life. Given its record as a resolute protector of commerce, it’s hard to be optimistic about the judgement it will make.

Michael Specter writes: On April 12, 1955, Jonas Salk, who had recently invented the polio vaccine, appeared on the television news show “See It Now” to discuss its impact on American society. Before the vaccine became available, dread of polio was almost as widespread as the disease itself. Hundreds of thousands fell ill, most of them children, many of whom died or were permanently disabled.

The vaccine changed all that, and Edward R. Murrow, the show’s host, asked Salk what seemed to be a reasonable question about such a valuable commodity: “Who owns the patent on this vaccine?” Salk was taken aback. “Well, the people,” he said. “There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

The very idea, to Salk, seemed absurd. But that was more than fifty years ago, before the race to mine the human genome turned into the biological Klondike rush of the twenty-first century. Between 1944, when scientists determined that DNA served as the carrier of genetic information, and 1953, when Watson and Crick described it as a double helix, the rate of discovery was rapid. Since then, and particularly after 2003, when work on the genome revealed that we are each built out of roughly twenty-five thousand genes, the promise of genomics has grown exponentially.

The intellectual and commercial bounty from that research has already been enormous, and it increases nearly every day, as we learn ways in which specific genes are associated with diseases — or with mechanisms that can prevent them. It took thousands of scientists and technicians more than a decade to complete the Human Genome Project, and cost well over a billion dollars. The same work can now be carried out in a day or two, in a single laboratory, for a thousand dollars—and the costs continue to plummet. As they do, we edge closer to one of modern science’s central goals: an era of personalized medicine, in which an individual’s treatment for scores of illnesses could be tailored to his specific genetic composition. That, of course, assumes that we own our own genes.

And yet, nearly twenty per cent of the genome — more than four thousand genes — are already covered by at least one U.S. patent. [Continue reading…]