Dominique Mosbergen writes: Researchers from the University of Adelaide in Australia argue in an upcoming book, The Dynamic Human, that humans really aren’t much smarter than other creatures — and that some animals may actually be brighter than we are.

“For millennia, all kinds of authorities — from religion to eminent scholars — have been repeating the same idea ad nauseam, that humans are exceptional by virtue that they are the smartest in the animal kingdom,” the book’s co-author Dr. Arthur Saniotis, a visiting research fellow with the university’s School of Medical Sciences, said in a written statement. “However, science tells us that animals can have cognitive faculties that are superior to human beings.”

Not to mention, ongoing research on intelligence and primate brain evolution backs the idea that humans aren’t the cleverest creatures on Earth, co-author Dr. Maciej Henneberg, a professor also at the School of Medical Sciences, told The Huffington Post in an email.

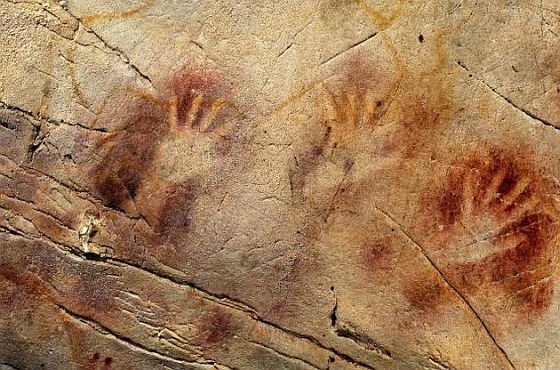

The researchers said the belief in the superiority of that human intelligence can be traced back around 10,000 years to the Agricultural Revolution, when humans began domesticating animals. The idea was reinforced with the advent of organized religion, which emphasized human beings’ superiority over other creatures. [Continue reading…]

At various times in my life, I’ve crossed paths with people possessing immense wealth and power, providing me with glimpses of the mindset of those who regard themselves as the most important people on this planet.

From what I can tell, the concentration of great power does not coincide with the expression of great intelligence. What is far more evident is a great sense of entitlement, which is to say a self-validating sense that power rests where power belongs and that the inequality in its distribution is a reflection of some kind of natural order.

Since this self-serving perception of hierarchical order operates among humans and since humans as a species wield so much more power than any other, it’s perhaps not surprising that we exhibit the same kind of hubris collectively that we see individually in the most dominant among us.

Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clear that our sense of superiority is rooted in ignorance.

Amit Majmudar writes: There may come a time when we cease to regard animals as inferior, preliminary iterations of the human—with the human thought of as the pinnacle of evolution so far—and instead regard all forms of life as fugue-like elaborations of a single musical theme.

Animals are routinely superhuman in one way or another. They outstrip us in this or that perceptual or physical ability, and we think nothing of it. It is only our kind of superiority (in the use of tools, basically) that we select as the marker of “real” superiority. A human being with an elephant’s hippocampus would end up like Funes the Memorious in the story by Borges; a human being with a dog’s olfactory bulb would become a Vermeer of scent, but his art would be lost on the rest of us, with our visually dominated brains. The poetry of the orcas is yet to be translated; I suspect that the whale sagas will have much more interesting things in them than the tablets and inscriptions of Sumer and Akkad.

If science should ever persuade people of this biological unity, it would be of far greater benefit to the species than penicillin or cardiopulmonary bypass; of far greater benefit to the planet than the piecemeal successes of environmental activism. We will have arrived, by study and reasoning, at the intuitive, mystical insights of poets.