Category Archives: Culture

DNA deciphers roots of modern Europeans

Carl Zimmer writes: For centuries, archaeologists have reconstructed the early history of Europe by digging up ancient settlements and examining the items that their inhabitants left behind. More recently, researchers have been scrutinizing something even more revealing than pots, chariots and swords: DNA.

On Wednesday in the journal Nature, two teams of scientists — one based at the University of Copenhagen and one based at Harvard University — presented the largest studies to date of ancient European DNA, extracted from 170 skeletons found in countries from Spain to Russia. Both studies indicate that today’s Europeans descend from three groups who moved into Europe at different stages of history.

The first were hunter-gatherers who arrived some 45,000 years ago in Europe. Then came farmers who arrived from the Near East about 8,000 years ago.

Finally, a group of nomadic sheepherders from western Russia called the Yamnaya arrived about 4,500 years ago. The authors of the new studies also suggest that the Yamnaya language may have given rise to many of the languages spoken in Europe today. [Continue reading…]

Some right-wing Europeans say Islam hasn’t contributed to Western culture. Here’s why they’re wrong

Akbar Ahmed writes: One of the right-wing tropes about Islam in Europe, which is making alarming inroads into the mainstream, is that it represents a “culture of backwardness, of retardedness, of barbarism” and has made no contribution to Western civilization. Islam provides an easy target considering that some 3,000 or more Europeans are estimated to have left for the Middle East in order to fight alongside the Islamic State. The savage beheadings and disgusting treatment of women and minorities confirm in the minds of many that Islam is incompatible with Western civilization. This has become a widely known, and even unthinkingly accepted, proposition. But is it correct?

Let us look at European history for answers. At least 10 things will surprise you: [Continue reading…]

When the song dies

The problem of translation

Gideon Lewis-Kraus writes: One Enlightenment aspiration that the science-fiction industry has long taken for granted, as a necessary intergalactic conceit, is the universal translator. In a 1967 episode of “Star Trek,” Mr. Spock assembles such a device from spare parts lying around the ship. An elongated chrome cylinder with blinking red-and-green indicator lights, it resembles a retracted light saber; Captain Kirk explains how it works with an off-the-cuff disquisition on the principles of Chomsky’s “universal grammar,” and they walk outside to the desert-island planet of Gamma Canaris N, where they’re being held hostage by an alien. The alien, whom they call The Companion, materializes as a fraction of sparkling cloud. It looks like an orange Christmas tree made of vaporized mortadella. Kirk grips the translator and addresses their kidnapper in a slow, patronizing, put-down-the-gun tone. The all-powerful Companion is astonished.

“My thoughts,” she says with some confusion, “you can hear them.”

The exchange emphasizes the utopian ambition that has long motivated universal translation. The Companion might be an ion fog with coruscating globules of viscera, a cluster of chunky meat-parts suspended in aspic, but once Kirk has established communication, the first thing he does is teach her to understand love. It is a dream that harks back to Genesis, of a common tongue that perfectly maps thought to world. In Scripture, this allowed for a humanity so well coordinated, so alike in its understanding, that all the world’s subcontractors could agree on a time to build a tower to the heavens. Since Babel, though, even the smallest construction projects are plagued by terrible delays. [Continue reading…]

Why climate action needs the arts

Andrew Simms writes: “Art is not a mirror to reflect reality,” wrote Bertolt Brecht, ”but a hammer with which to shape it.” His view was clearly shared by the judges of Anglian Ruskin University’s recent sustainable art prize. The winning piece was a large tombstone themed on climate change, blackened by oil and carrying the words “Lest we forget those who denied.”

The fact that there were also the names of six prominent climate sceptics on the tombstone led the Telegraph newspaper to denounce it as “tasteless” and “obnoxious”, and for one of those named, Christopher Monckton, to claim the artwork constituted a death threat.

From Goya, who darkly interpreted the horrors of Europe at war, to the romantics who conjured the dark satanic mills of the industrial revolution, art has always explored and assimilated the experience of upheaval. More than that, from Milton’s pamphleteering, to the British artists and writers who fought in the Spanish civil war against Franco’s fascism, art has put itself at the service of explicitly political campaigns throughout history.

It is only odd, perhaps, that it has taken climate change so long to become a significant and controversial theme for the arts. The relative absence from daily political and cultural life of something as fundamental as a threat to a climate stable for humanity, has been weird. There will always be those who argue that didactic art is bad art. But equally, art that doesn’t notice, or remains unaffected by, epochal shifts in the world it inhabits, is variously asleep, suffocatingly self-absorbed or simply not looking.

If anything, the willingness to accept high-profile sponsorship from fossil fuel companies suggests that the art establishment has been worse than indifferent, and actively obstructive to the challenge of tackling climate upheaval. The social licence to operate, and normalisation that such cultural relationships gift to oil companies, can dissipate the urgency for action and sponsorship can seek to directly influence the climate debate.

That is all now changing. [Continue reading…]

The neuroscience of a sense of place

Rick Paulas writes: Comedian Eddie Pepitone once said — and I’m paraphrasing here — that there are no great neighborhoods in Los Angeles, only great blocks. The stretch of Echo Park on Sunset Boulevard between Glendale and Logan is one. The establishments on that short stretch include an upscale wine bar, a hipster concert venue, a vegan restaurant, a deep dish pizza place, cheap thrift stores, not-so-cheap “vintage” stores selling roughly the same stuff, a check-cashing joint, a few fast food chains, and even a supermarket for time travelers.

While it’s not the most diverse cross-section you’ll find in the city, the block can be used as a social barometer when brought up in conversations. Mention the stretch, and whatever landmark the other person’s familiar with tells the tale of the socioeconomic sphere they inhabit; the landmark that puts a gleam of recognition in the other person’s eye says everything about their story.

Blocks and neighborhoods aren’t concrete concepts that mean the same thing to everyone, unlike, say, things like “apple” or “sky.” Points of reference shift depending on the person that’s using that reference, so blocks/neighborhoods are more like alternate realities laid atop one another, like plastic sheets on an overhead projector. There’s even a phrase for the study of this murky concept: mental maps. They can help us understand why some neighborhoods thrive, others die, and how changes are made.

The theory of mental (or cognitive) maps was first developed in 1960 by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Kevin Lynch in his book The Image of the City. Rather than relying on how cartographers saw a city, Lynch asked residents to draw a map, from memory, depicting how their city was arranged. He found that five elements compose a person’s understanding of where they are: landmarks, paths, edges, districts, and nodes. Landmarks are reference points, paths connect them, edges mark boundaries, and the other elements define larger areas that contain some combination of each of those designations.

Neuroscience backs up Lynch’s findings. In 1971, Jon O’Keefe discovered “place cells” in the hippocampus, neurons that activate when an animal enters an environment. The neurons calculate a current location based on what the animal can see, as well as through “dead reckoning” — that is, accounting based on subconscious calculations using previous positions in the recent past and how quickly it traveled over a stretch of time. In 2005, husband-and-wife team Edvard and May-Britt Moser discovered “grid cells,” neurons that fire in a grid-like pattern to measure distances and direction. O’Keefe and the Mosers all won Nobel Prizes in 2014 for their discoveries. [Continue reading…]

Why do Americans waste so much food?

Were we happier in the Stone Age?

Yuval Noah Harari writes: Over the last decade, I have been writing a history of humankind, tracking down the transformation of our species from an insignificant African ape into the master of the planet. It was not easy to understand what turned Homo sapiens into an ecological serial killer; why men dominated women in most human societies; or why capitalism became the most successful religion ever. It wasn’t easy to address such questions because scholars have offered so many different and conflicting answers. In contrast, when it came to assessing the bottom line – whether thousands of years of inventions and discoveries have made us happier – it was surprising to realise that scholars have neglected even to ask the question. This is the largest lacuna in our understanding of history.

Though few scholars have studied the long-term history of happiness, almost everybody has some idea about it. One common preconception – often termed “the Whig view of history” – sees history as the triumphal march of progress. Each passing millennium witnessed new discoveries: agriculture, the wheel, writing, print, steam engines, antibiotics. Humans generally use newly found powers to alleviate miseries and fulfil aspirations. It follows that the exponential growth in human power must have resulted in an exponential growth in happiness. Modern people are happier than medieval people, and medieval people were happier than stone age people.

But this progressive view is highly controversial. Though few would dispute the fact that human power has been growing since the dawn of history, it is far less clear that power correlates with happiness. The advent of agriculture, for example, increased the collective power of humankind by several orders of magnitude. Yet it did not necessarily improve the lot of the individual. For millions of years, human bodies and minds were adapted to running after gazelles, climbing trees to pick apples, and sniffing here and there in search of mushrooms. Peasant life, in contrast, included long hours of agricultural drudgery: ploughing, weeding, harvesting and carrying water buckets from the river. Such a lifestyle was harmful to human backs, knees and joints, and numbing to the human mind.

In return for all this hard work, peasants usually had a worse diet than hunter-gatherers, and suffered more from malnutrition and starvation. Their crowded settlements became hotbeds for new infectious diseases, most of which originated in domesticated farm animals. Agriculture also opened the way for social stratification, exploitation and possibly patriarchy. From the viewpoint of individual happiness, the “agricultural revolution” was, in the words of the scientist Jared Diamond, “the worst mistake in the history of the human race”.

The case of the agricultural revolution is not a single aberration, however. Themarch of progress from the first Sumerian city-states to the empires of Assyria and Babylonia was accompanied by a steady deterioration in the social status and economic freedom of women. The European Renaissance, for all its marvellous discoveries and inventions, benefited few people outside the circle of male elites. The spread of European empires fostered the exchange of technologies, ideas and products, yet this was hardly good news for millions of Native Americans, Africans and Aboriginal Australians.

The point need not be elaborated further. Scholars have thrashed the Whig view of history so thoroughly, that the only question left is: why do so many people still believe in it? [Continue reading…]

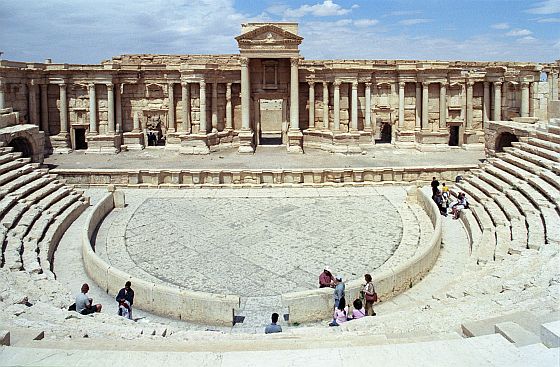

Palmyra and its ancient ruins have fallen to ISIS

The New York Times reports: Islamic State militants swept into the desert city of Palmyra in central Syria on Wednesday, and by evening were in control of it, residents and Syrian state news media said, a victory that gives them another strategically important prize five days after the group seized the Iraqi city of Ramadi.

Palmyra has extra resonance, with its grand complex of 2,000-year-old colonnades and tombs, one of the world’s most magnificent remnants of antiquity, as well as the grimmer modern landmark of Tadmur Prison, where Syrian dissidents have languished over the decades.

But for the fighters on the ground, the city of 50,000 people is significant because it sits among gas fields and astride a network of roads across the country’s central desert. Palmyra’s vast unexcavated antiquities could also provide significant revenue through illegal trafficking.

Control of Palmyra gives the Islamic State command of roads leading from its strongholds in eastern Syria to Damascus and the other major cities of the populated west, as well as new links to western Iraq, the other half of its self-declared caliphate.

The advance, in which residents described soldiers and the police fleeing, wounded civilians unable to reach hospitals and museum workers hurrying to pack up antiquities, comes even as the United States is scrambling to come up with a response to the loss of Ramadi, the capital of Iraq’s Anbar Province.

The two successes, at opposite ends of a battlefield sprawling across two countries, showed the Islamic State’s ability to shake off setbacks and advance on multiple fronts, less than two months after it was driven from the Iraqi city of Tikrit — erasing any notion that the group had suffered a game-changing blow. [Continue reading…]

Prof Kevin Butcher writes: From modest beginnings in the 1st Century BC, Palmyra gradually rose to prominence under the aegis of Rome until, during the 3rd Century AD, the city’s rulers challenged Roman power and created an empire of their own that stretched from Turkey to Egypt.

The story of its Queen Zenobia, who fought against the Roman Emperor Aurelian, is well known; but it is less well-known that Palmyra also fought another empire: that of the Sasanian Persians.

In the middle of the third century, when the Sasanians invaded the Roman Empire and captured the Emperor Valerian, it was the Palmyrenes who defeated them and drove them back across the Euphrates.

For several decades Rome had to rely on Palmyrene power to prop up its declining influence in the east.

Palmyra was a great Middle Eastern achievement, and was unlike any other city of the Roman Empire.

It was quite unique, culturally and artistically. In other cities the landed elites normally controlled affairs, whereas in Palmyra a merchant class dominated the political life, and the Palmyrenes specialised in protecting merchant caravans crossing the desert. [Continue reading…]

ISIS advance in Syria endangers ancient ruins at Palmyra

The New York Times reports: Islamic State militants advanced to the outskirts of the Syrian town of Palmyra on Thursday, putting the extremist group within striking distance of some of the world’s most magnificent antiquities.

That raised fears that the ancient city of Palmyra, with its complex of columns, tombs and ancient temples dating to the first century A.D., could be looted or destroyed. Militants from the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, have already destroyed large parts of ancient sites at Nimrud, Hatra and Nineveh in Iraq. Islamic State leaders denounce pre-Islamic art and architecture as idolatrous even as they sell smaller, more portable artifacts to finance their violent rampage through the region.

The fighting on Thursday took place little more than a mile from the city’s grand 2,000-year-old ruins, which stand as the crossroad of Greek, Roman, Persian and Islamic cultures.

People in Palmyra described a state of anxiety and chaos, with residents trying to flee the northern neighborhoods. [Continue reading…]

Big drop in share of Americans calling themselves Christian

The New York Times reports: The Christian share of adults in the United States has declined sharply since 2007, affecting nearly all major Christian traditions and denominations, and crossing age, race and region, according to an extensive survey by the Pew Research Center.

Seventy-one percent of American adults were Christian in 2014, the lowest estimate from any sizable survey to date, and a decline of 5 million adults and 8 percentage points since a similar Pew survey in 2007.

The Christian share of the population has been declining for decades, but the pace rivals or even exceeds that of the country’s most significant demographic trends, like the growing Hispanic population. It is not confined to the coasts, the cities, the young or the other liberal and more secular groups where one might expect it, either.

“The decline is taking place in every region of the country, including the Bible Belt,” said Alan Cooperman, the director of religion research at the Pew Research Center and the lead editor of the report. [Continue reading…]

The world beyond your head

Matthew Crawford, author of The World Beyond Your Head, talks to Ian Tuttle.

Crawford: Only by excluding all the things that grab at our attention are we able to immerse ourselves in something worthwhile, and vice versa: When you become absorbed in something that is intrinsically interesting, that burden of self-regulation is greatly reduced.

Tuttle: To the present-day consequences. The first, and perhaps most obvious, consequence is a moral one, which you address in your harrowing chapter on machine gambling: “If we have no robust and demanding picture of what a good life would look like, then we are unable to articulate any detailed criticism of the particular sort of falling away from a good life that something like machine gambling represents.” To modern ears that sentence sounds alarmingly paternalistic. Is the notion of “the good life” possible in our age? Or is it fundamentally at odds with our political and/or philosophical commitments?

Crawford: Once you start digging into the chilling details of machine gambling, and of other industries such as mobile gaming apps that emulate the business model of “addiction by design” through behaviorist conditioning, you may indeed start to feel a little paternalistic — if we can grant that it is the role of a pater to make scoundrels feel unwelcome in the town.

According to the prevailing notion, freedom manifests as “preference-satisfying behavior.” About the preferences themselves we are to maintain a principled silence, out of deference to the autonomy of the individual. They are said to express the authentic core of the self, and are for that reason unavailable for rational scrutiny. But this logic would seem to break down when our preferences are the object of massive social engineering, conducted not by government “nudgers” but by those who want to monetize our attention.

My point in that passage is that liberal/libertarian agnosticism about the human good disarms the critical faculties we need even just to see certain developments in the culture and economy. Any substantive notion of what a good life requires will be contestable. But such a contest is ruled out if we dogmatically insist that even to raise questions about the good life is to identify oneself as a would-be theocrat. To Capital, our democratic squeamishness – our egalitarian pride in being “nonjudgmental” — smells like opportunity. Commercial forces step into the void of cultural authority, where liberals and libertarians fear to tread. And so we get a massive expansion of an activity — machine gambling — that leaves people compromised and degraded, as well as broke. And by the way, Vegas is no longer controlled by the mob. It’s gone corporate.

And this gets back to what I was saying earlier, about how our thinking is captured by obsolete polemics from hundreds of years ago. Subjectivism — the idea that what makes something good is how I feel about it — was pushed most aggressively by Thomas Hobbes, as a remedy for civil and religious war: Everyone should chill the hell out. Live and let live. It made sense at the time. This required discrediting all those who claim to know what is best. But Hobbes went further, denying the very possibility of having a better or worse understanding of such things as virtue and vice. In our time, this same posture of value skepticism lays the public square bare to a culture industry that is not at all shy about sculpting souls – through manufactured experiences, engineered to appeal to our most reliable impulses. That’s how one can achieve economies of scale. The result is a massification of the individual. [Continue reading…]

From chimps to bees and bacteria, how animals hold elections

By Robert John Young, University of Salford

Lots of people find elections dull, but there’s nothing boring about the political manoeuvres that take place in the animal kingdom. In the natural world, jockeying for advantage, whether this is conscious or merely mechanical, can be a matter of life or death.

Chimpanzees, our closest relatives, are highly political. They’re smart enough to realise that in the natural world brute strength will only get you so far – getting to the top of a social group and remaining there requires political guile.

It’s all about making friends and influencing others. Chimps make friends by grooming each other and forming alliances; this behaviour is especially prominent in males wishing to be group leader. In times of dispute they call upon their friends for assistance or when they sense a coup may be successful. And the ruling group either reaffirms its position or a new group grabs control – but having the weight of numbers is normally critical to success.

IFAW, CC BY-NC

Back in the 1980s, the leading Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal spent six years researching the world’s largest captive colony for his classic book Chimpanzee Politics. He soon realised that, in addition to forming cliques, chimp politics still involves some degree of aggression.

Humans in modern societies have largely replaced antagonistic takeovers with voting. Chimps do not, however, live in a democratic society. For them, the social structure of the ruling party is usually one based on male hierarchy, where dominant individuals have best access to the resources available – usually food and females.

Jihadists destroy proposed world heritage site in Mali

The Associated Press reports: Jihadists have destroyed a mausoleum in central Mali that had been submitted as a U.N. World Heritage site, leaving behind a warning that they will come after all those who don’t follow their strict version of Islam, a witness said Monday.

The dynamite attack on the mausoleum of Cheick Amadou Barry mirrors similar ones that were carried out in northern Mali in 2012 when jihadists seized control of the major towns there. The destruction also comes as concerns grow about the emergence of a new extremist group active much further south and closer to the capital.

Barry was a marabout, or important Islamic religious leader, in the 19th century who helped to spread Islam among the animists of central Mali. One of his descendants, Bologo Amadou Barry, confirmed to The Associated Press that the site had been partially destroyed in Hamdallahi village on Sunday night.

The jihadists left behind a note on Sunday warning they would attack all those who did not follow the teachings of Islam’s prophet.

“They also threatened France and the U.N. peacekeepers and all those who work with them,” Bologo Amadou Barry said. [Continue reading…]

Chain reactions spreading ideas through science and culture

David Krakauer writes: On Dec. 2, 1942, just over three years into World War II, President Roosevelt was sent the following enigmatic cable: “The Italian navigator has landed in the new world.” The accomplishments of Christopher Columbus had long since ceased to be newsworthy. The progress of the Italian physicist, Enrico Fermi, navigator across the territories of Lilliputian matter — the abode of the microcosm of the atom — was another thing entirely. Fermi’s New World, discovered beneath a Midwestern football field in Chicago, was the province of newly synthesized radioactive elements. And Fermi’s landing marked the earliest sustained and controlled nuclear chain reaction required for the construction of an atomic bomb.

This physical chain reaction was one of the links of scientific and cultural chain reactions initiated by the Hungarian physicist, Leó Szilárd. The first was in 1933, when Szilárd proposed the idea of a neutron chain reaction. Another was in 1939, when Szilárd and Einstein sent the now famous “Szilárd-Einstein” letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt informing him of the destructive potential of atomic chain reactions: “This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable — though much less certain — that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed.”

This scientific information in turn generated political and policy chain reactions: Roosevelt created the Advisory Committee on Uranium which led in yearly increments to the National Defense Research Committee, the Office of Scientific Research and Development, and finally, the Manhattan Project.

Life itself is a chain reaction. Consider a cell that divides into two cells and then four and then eight great-granddaughter cells. Infectious diseases are chain reactions. Consider a contagious virus that infects one host that infects two or more susceptible hosts, in turn infecting further hosts. News is a chain reaction. Consider a report spread from one individual to another, who in turn spreads the message to their friends and then on to the friends of friends.

These numerous connections that fasten together events are like expertly arranged dominoes of matter, life, and culture. As the modernist designer Charles Eames would have it, “Eventually everything connects — people, ideas, objects. The quality of the connections is the key to quality per se.”

Dominoes, atoms, life, infection, and news — all yield domino effects that require a sensitive combination of distances between pieces, physics of contact, and timing. When any one of these ingredients is off-kilter, the propagating cascade is likely to come to a halt. Premature termination is exactly what we might want to happen to a deadly infection, but it is the last thing that we want to impede an idea. [Continue reading…]

The cautious rise of atheism and religious doubt in the Arab world

Ahmed Benchemsi writes: Last December, Dar Al Ifta, a venerable Cairo-based institution charged with issuing Islamic edicts, cited an obscure poll according to which the exact number of Egyptian atheists was 866. The poll provided equally precise counts of atheists in other Arab countries: 325 in Morocco, 320 in Tunisia, 242 in Iraq, 178 in Saudi Arabia, 170 in Jordan, 70 in Sudan, 56 in Syria, 34 in Libya, and 32 in Yemen. In total, exactly 2,293 nonbelievers in a population of 300 million.

Many commentators ridiculed these numbers. The Guardian asked Rabab Kamal, an Egyptian secularist activist, if she believed the 866 figure was accurate. “I could count more than that number of atheists at Al Azhar University alone,” she replied sarcastically, referring to the Cairo-based academic institution that has been a center of Sunni Islamic learning for almost 1,000 years. Brian Whitaker, a veteran Middle East correspondent and the author of Arabs Without God, wrote, “One possible clue is that the figure for Jordan (170) roughly corresponds to the membership of a Jordanian atheist group on Facebook. So it’s possible that the researchers were simply trying to identify atheists from various countries who are active in social media.”

Even by that standard, Dar Al Ifta’s figures are rather low. When I recently searched Facebook in both Arabic and English, combining the word “atheist” with names of different Arab countries, I turned up over 250 pages or groups, with memberships ranging from a few individuals to more than 11,000. And these numbers only pertain to Arab atheists (or Arabs concerned with the topic of atheism) who are committed enough to leave a trace online. “My guess is, every Egyptian family contains an atheist, or at least someone with critical ideas about Islam,” an atheist compatriot, Momen, told Egyptian historian Hamed Abdel-Samad recently. “They’re just too scared to say anything to anyone.”

While Arab states downplay the atheists among their citizens, the West is culpable in its inability to even conceive of an Arab atheist. In Western media, the question is not if Arabs are religious, but rather to what extent their (assumed) religiosity can harm the West. In Europe, the debate focuses on immigration (are “Muslim immigrants” adverse to secular freedoms?) while in the United States, the central topic is terrorism (are “Muslims” sympathetic to it?). As for the political debate, those on the right suspect “Muslims” of being hostile to individual freedoms and sympathetic to jihad, while leftists seek to exonerate “Muslims” by highlighting their “peaceful” and “moderate” religiosity. But no one is letting the Arab populations off the hook for their Muslimhood. Both sides base their argument on the premise that when it comes to Arab people, religiosity is an unquestionable given, almost an ethnic mandate embedded in their DNA. [Continue reading…]

Afghan novelist: ‘We live in a vacuum, lacking heroes and ideals’

Mujib Mashal writes: Four large clocks tick out of sync, puncturing the silence of his Soviet-built apartment. A half-burned candle sits next to a stack of books. A small television is covered in soot.

This is where Rahnaward Zaryab, Afghanistan’s most celebrated novelist, locks himself up for weeks at a time, lost in bottles of smuggled vodka and old memories of Kabul, a capital city long transformed by war and money.

“We live in a vacuum, lacking heroes and ideals,” Mr. Zaryab reads from his latest manuscript, handwritten on the back of used paper. The smoke from his Pine cigarette, a harsh South Korean brand, clings to yellowed walls. “The heroes lie in dust, the ideals are ridiculed.”

The product of a rare period of peace and tolerance in Afghan history, Mr. Zaryab’s work first flourished in the 1970s, before the country was unraveled by invasion and civil war. Afghanistan still had a vibrant music and theater scene, and writers had a broad readership that stretched beyond just the political elite.

“I would receive letters from girls that would smell of perfume when you opened them,” Mr. Zaryab, who is 70, remembered fondly.

Mr. Zaryab’s stories are informed by his readings of Western philosophy and literature, the writer Homaira Qaderi said. He was educated on scholarships in New Zealand and Britain. But his heroes are indigenous and modest, delicately questioning the dogma and superstitions of a conservative society.

“He is the first writer to focus on the structure of stories, with the eye of someone well read,” Ms. Qaderi said. “We call him the father of new storytelling in Afghanistan.”

But after he became the standard-bearer for Afghan literature, Mr. Zaryab was forced to watch as Kabul, the muse he idealized as a city of music and chivalry in most of his 17 books, fell into rubble and chaos.

Some of the chaos has eased over the past decade, but that has caused him even more pain. He loathes how Kabul has been rebuilt: on a foundation of American cash and foreign values, paving over Afghan culture.

“Money, money, money,” he said, cringing. “Everyone is urged to make money, in any way they can. Art, culture and literature have been forgotten completely.” [Continue reading…]