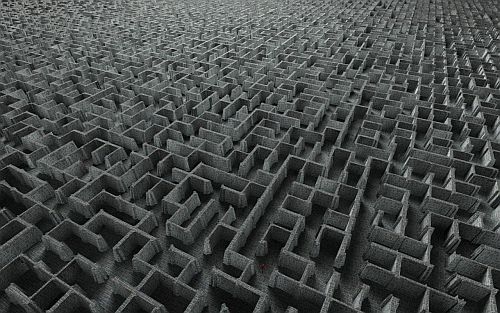

After almost a decade of a US-led global war on terrorism, America’s approach to the issue has barely advanced from being a deadly game of Whack-a-Mole.

On CBS, Scott Pelley asked Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton: “I wonder if there’s anything about U.S. foreign policy that needs to change in your estimation to put more pressure on these terrorist groups where they live, like in Pakistan?”

“Well, we are doing that. And we’re increasing it. We’re expecting more from it. This is a global threat. We have probably the best police work in the world. But we are also the biggest target. And therefore, we just have to be better than everybody else,” Clinton replied.

Earlier in the interview she said: “We’ve made it very clear [to the Pakistani government] that, if, heaven forbid, that an attack like this [in Times Square], if we can trace back to Pakistan, were to have been successful, there would be very severe consequences.”

The US will start bombing Pakistan? Special Forces will start conducting operations in North Waziristan? Clinton would not specify what form these severe consequences might take.

In response to the Times Square incident, Richard Clarke, former counter-terrorism coordinator for the Bush administration writes:

The reason such attacks are hard to stop is rooted in the identity of the attackers. They often seem to be successful or well-educated members of society, uninvolved in any form of radicalism. But then, the drip-drip of terrorist propaganda — either on the Internet or circulated through friends — has its effect. They quietly make contact with radical groups overseas, perhaps even traveling abroad for training and indoctrination. They throw away the life they have made in the West and agree to stage an attack. Faisal Shahzad, the alleged Times Square terrorist, fits that profile, as have others in the United States and Europe.

For U.S. intelligence and law enforcement authorities, these newly minted terrorists are the hardest to stop. They may not be part of any known cell; there is no reason for their phones or e-mail accounts to come under surveillance. When they buy rifles, handguns, tanks of propane gas or fertilizer, they are doing nothing out of the ordinary in American society.

If they succeed in inflicting harm on us with terrorist acts designed to rivet media and public attention, our political debate may once again be as wrongheaded as it will be predictable. Some elected officials will claim that their party would have done a much better job protecting the country. Critics of America’s Middle East policy — or our energy policy, or our foreign policy writ large — will also fault whatever administration is in power.

Likewise, in a 60 Minutes report that aired last night, the prism through which the issue is filtered is one in which individuals are turned into the tools of a deadly ideology. Vulnerable young men are in jeopardy of being recruited by merciless ideologues and terrorist planners.

But as Scott Atran points out, the idea that Shahzad and those like him have to be recruited, does not fit the evidence.

Shahzad was also apparently inspired by the online rhetoric of Anwar al-Awlaki, a former preacher at a Northern Virginia mosque who gained international notoriety for blessing the suicide mission of the failed Christmas airplane bomber, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallib, and for Facebook communications with Major Nadal Hasan, an American-born Muslim psychiatrist who killed thirteen fellow soldiers at Fort Hood in November 2009. Although many are ready to leap to the conclusion that Awlaki helped to “brainwash” and “indoctrinate” these jihadi wannabes, it is much more likely that they sought out the popular Internet preacher because they already self-radicalized to the point of wanting reassurance and further guidance. “The movement is from the bottom up,” notes forensic psychiatrist and former CIA case officer Marc Sageman, “just like you saw Major Hasan send twenty-one e-mails to al-Awlaki, who sends him back two, you have people seeking these guys and asking them for advice.”

The CBS report, stuck on the track that recruitment is a central issue, homes in on the role of the internet. The would-be terrorist is someone whose deadly intent is sure to be triggered by something he sees online.

Phillip Mudd, who until a few months ago was the senior intelligence advisor to the FBI and its director says:

They’re seeing images, for example, of children and women in places like Palestine and Iraq, they’re seeing sermons of people who explain in simple, compelling, and some cases magnetic terms why it’s important that they join the jihad. They’re seeing images, and messages that confirm a path that they’re already thinking of taking.

CBS helpfully provides such an image, but predictably neglects to add any commentary.

What are we seeing? An Israeli soldier terrorizing a Palestinian mother and her two girls.

And there we have it: exactly the kind of image the foments terrorism.

Viewed through the American counter-terrorism lens, the problem lies with the propagation of the image and the violent reaction such an image can provoke. Why? Because any serious consideration of the foreign policy issues that the image signals is still off-limits.

But here’s what everyone in the Middle East sees: An Israeli Jew brandishing an American-made weapon, serving America’s closest ally in the Middle East, is threatening a Muslim family. This is the narrative that no amount of spin or cleverly fought battles in a war of ideas, can undo.

Yet here is the foreign policy dilemma for Washington: How can the United States adopt a posture in the Middle East that acknowledges the role America has played in fueling terrorism, without appearing to capitulate to terrorist demands?

The answer is to trust in the universally recognized truth: actions speak louder than words.

What Obama does in Pakistan matters more than what he said in Cairo.

In April 2003, the Bush administration made a step in the right direction when it withdrew American troops from Saudi Arabia. The moved turned out to be of little consequence since it was triggered by utterly false expectations about the war in Iraq. Yet there was an implicit recognition: the presence of American soldiers in close proximity to Islam’s holiest sites sends an ugly message to the Muslim world.

Seven years later, as the Obama administration puts increased pressure on the Pakistani government to launch a major offensive in North Waziristan — an operation that would yet again result in the displacement of tens of thousands of civilians — and as the CIA continues to expand a drone war that has resulted in hundreds of civilian deaths, what kind of signal is this sending to those who might now contemplate following in the footsteps of Faisal Shahzad?

After three Frontier Corps soldiers were killed in a NATO helicopter attack on a Pakistani border post last week, the Pakistani government cut off supplies to Afghanistan by closing the Torkham border crossing. It was the easiest way of sending a message to Washington that killing Pakistani soldiers is unacceptable.

After three Frontier Corps soldiers were killed in a NATO helicopter attack on a Pakistani border post last week, the Pakistani government cut off supplies to Afghanistan by closing the Torkham border crossing. It was the easiest way of sending a message to Washington that killing Pakistani soldiers is unacceptable.

American operations in South Asia… are threatening to upset [a] fragile balance between Islam and nationalism in the Pakistani military. The army’s members can hardly avoid sharing the broader population’s bitter hostility to U.S. policy. To judge by retired and serving officers, this includes the genuine conviction that either the Bush administration or Israel was responsible for 9/11. Inevitably therefore, there was deep opposition throughout the army after 2001 to American pressure to crack down on the Afghan Taliban and their Pakistani sympathizers. “We are being ordered to launch a Pakistani civil war for the sake of America,” an officer told me in 2002. “Why on earth should we? Why should we commit suicide for you?”

American operations in South Asia… are threatening to upset [a] fragile balance between Islam and nationalism in the Pakistani military. The army’s members can hardly avoid sharing the broader population’s bitter hostility to U.S. policy. To judge by retired and serving officers, this includes the genuine conviction that either the Bush administration or Israel was responsible for 9/11. Inevitably therefore, there was deep opposition throughout the army after 2001 to American pressure to crack down on the Afghan Taliban and their Pakistani sympathizers. “We are being ordered to launch a Pakistani civil war for the sake of America,” an officer told me in 2002. “Why on earth should we? Why should we commit suicide for you?” The delegation represents fighters loyal to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, 60, one of the most brutal of Afghanistan’s former resistance fighters who leads a part of the insurgency against American, NATO and Afghan forces in the north and northeast of the country.

The delegation represents fighters loyal to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, 60, one of the most brutal of Afghanistan’s former resistance fighters who leads a part of the insurgency against American, NATO and Afghan forces in the north and northeast of the country. If Colonel Imam personifies the double edge of Pakistan’s policy toward the Taliban, he also embodies the deep connection Pakistan has to the Afghan insurgents, and possibly the key to controlling them.

If Colonel Imam personifies the double edge of Pakistan’s policy toward the Taliban, he also embodies the deep connection Pakistan has to the Afghan insurgents, and possibly the key to controlling them.