Julie Sedivy writes: Reading medieval literature, it’s hard not to be impressed with how much the characters get done—as when we read about King Harold doing battle in one of the Sagas of the Icelanders, written in about 1230. The first sentence bristles with purposeful action: “King Harold proclaimed a general levy, and gathered a fleet, summoning his forces far and wide through the land.” By the end of the third paragraph, the king has launched his fleet against a rebel army, fought numerous battles involving “much slaughter in either host,” bound up the wounds of his men, dispensed rewards to the loyal, and “was supreme over all Norway.” What the saga doesn’t tell us is how Harold felt about any of this, whether his drive to conquer was fueled by a tyrannical father’s barely concealed contempt, or whether his legacy ultimately surpassed or fell short of his deepest hopes.

Jump ahead about 770 years in time, to the fiction of David Foster Wallace. In his short story “Forever Overhead,” the 13-year-old protagonist takes 12 pages to walk across the deck of a public swimming pool, wait in line at the high diving board, climb the ladder, and prepare to jump. But over these 12 pages, we are taken into the burgeoning, buzzing mind of a boy just erupting into puberty—our attention is riveted to his newly focused attention on female bodies in swimsuits, we register his awareness that others are watching him as he hesitates on the diving board, we follow his undulating thoughts about whether it’s best to do something scary without thinking about it or whether it’s foolishly dangerous not to think about it.

These examples illustrate Western literature’s gradual progression from narratives that relate actions and events to stories that portray minds in all their meandering, many-layered, self-contradictory complexities. I’d often wondered, when reading older texts: Weren’t people back then interested in what characters thought and felt? [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Attention to the Unseen

On the happy life

Massimo Pigliucci writes: Lucius Annaeus Seneca is a towering and controversial figure of antiquity. He lived from 4 BCE to 65 CE, was a Roman senator and political adviser to the emperor Nero, and experienced exile but came back to Rome to become one of the wealthiest citizens of the Empire. He tried to steer Nero toward good governance, but in the process became his indirect accomplice in murderous deeds. In the end, he was ‘invited’ to commit suicide by the emperor, and did so with dignity, in the presence of his friends.

Seneca wrote a number of tragedies that directly inspired William Shakespeare, but was also one of the main exponents of the Stoic school of philosophy, which has made a surprising comeback in recent years. Stoicism teaches us that the highest good in life is the pursuit of the four cardinal virtues of practical wisdom, temperance, justice and courage – because they are the only things that always do us good and can never be used for ill. It also tells us that the key to a serene life is the realisation that some things are under our control and others are not: under our control are our values, our judgments, and the actions we choose to perform. Everything else lies outside of our control, and we should focus our attention and efforts only on the first category.

Seneca wrote a series of philosophical letters to his friend Lucilius when he was nearing the end of his life. The letters were clearly meant for publication, and represent a sort of philosophical testament for posterity. I chose letter 92, ‘On the Happy Life’, because it encapsulates both the basic tenets of Stoic philosophy and some really good advice that is still valid today.

The first thing to understand about this letter is the title itself: ‘happy’ here does not have the vague modern connotation of feeling good, but is the equivalent of the Greek word eudaimonia, recently adopted also by positive psychologists, and which is best understood as a life worth living. [Continue reading…]

Trees have their own songs

Ed Yong writes: Just as birders can identify birds by their melodious calls, David George Haskell can distinguish trees by their sounds. The task is especially easy when it rains, as it so often does in the Ecuadorian rainforest. Depending on the shapes and sizes of their leaves, the different plants react to falling drops by producing “a splatter of metallic sparks” or “a low, clean, woody thump” or “a speed-typist’s clatter.” Every species has its own song. Train your ears (and abandon the distracting echoes of a plastic rain jacket) and you can carry out a botanical census through sound alone.

“I’ve taught ornithology to students for many years,” says Haskell, a natural history writer and professor of biology at Sewanee. “And I challenge my students: Okay, now that you’ve learned the songs of 100 birds, your task is to learn the sounds of 20 trees. Can you tell an oak from a maple by ear? I have them go out, pour their attention into their ears, and harvest sounds. It’s an almost meditative experience. And from that, you realize that trees sound different, and they have amazing sounds coming from them. Our unaided ears can hear how a maple tree changes its voice as a soft leaves of early spring change into the dying one of autumn.”

This acoustic world is open to everyone, but most of us never enter it. It just seems so counter-intuitive—not to mention a little hokey—to listen to trees. But Haskell does listen, and he describes his experiences with sensuous prose in his enchanting new book The Songs of Trees. A kind of naturalist-poet, Haskell makes a habit of returning to the same places and paying “repeated sensory attention” to them. “I like to sit down and listen, and turn off the apps that come pre-installed in my body,” he says. Humans may be a visual species, but “sounds reveals things that are hidden from our eyes because the vibratory energy of the world comes around barriers and through the ground. Through sound, we come to know the place.” [Continue reading…]

The benefits of solitude

Michael Harris writes: On April 14, 1934, Richard Byrd went out for his daily walk. The air was the usual temperature: minus 57 degrees Fahrenheit. He stepped steadily through the drifts of snow, making his rounds. And then he paused to listen. Nothing.

He attended, a little startled, to the cloud-high and over-powering silence he had stepped into. For miles around the only other life belonged to a few stubborn microbes that clung to sheltering shelves of ice. It was only 4 p.m., but the land quavered in a perpetual twilight. There was—was there?—some play on the chilled horizon, some crack in the bruised Antarctic sky. And then, unaccountably, Richard Byrd’s universe began to expand.

Later, back in his hut, huddled by a makeshift furnace, Byrd wrote in his diary:

Here were imponderable processes and forces of the cosmos, harmonious and soundless. Harmony, that was it! That was what came out of the silence—a gentle rhythm, the strain of a perfect chord, the music of the spheres, perhaps.

It was enough to catch that rhythm, momentarily to be myself a part of it. In that instant I could feel no doubt of man’s oneness with the universe.

Admiral Byrd had volunteered to staff a weather base near the South Pole for five winter months. But the reason he was there alone was far less concrete. Struggling to explain his reasons, Byrd admitted that he wanted “to know that kind of experience to the full . . . to taste peace and quiet and solitude long enough to find out how good they really are.” He was also after a kind of personal liberty, for he believed that “no man can hope to be completely free who lingers within reach of familiar habits.” [Continue reading…]

Invisible manipulators of your mind

Tamsin Shaw writes: We are living in an age in which the behavioral sciences have become inescapable. The findings of social psychology and behavioral economics are being employed to determine the news we read, the products we buy, the cultural and intellectual spheres we inhabit, and the human networks, online and in real life, of which we are a part. Aspects of human societies that were formerly guided by habit and tradition, or spontaneity and whim, are now increasingly the intended or unintended consequences of decisions made on the basis of scientific theories of the human mind and human well-being.

The behavioral techniques that are being employed by governments and private corporations do not appeal to our reason; they do not seek to persuade us consciously with information and argument. Rather, these techniques change behavior by appealing to our nonrational motivations, our emotional triggers and unconscious biases. If psychologists could possess a systematic understanding of these nonrational motivations they would have the power to influence the smallest aspects of our lives and the largest aspects of our societies.

Michael Lewis’s The Undoing Project seems destined to be the most popular celebration of this ongoing endeavor to understand and correct human behavior. It recounts the complex friendship and remarkable intellectual partnership of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, the psychologists whose work has provided the foundation for the new behavioral science. It was their findings that first suggested we might understand human irrationality in a systematic way. When our thinking errs, they claimed, it does so predictably. Kahneman tells us that thanks to the various counterintuitive findings—drawn from surveys—that he and Tversky made together, “we now understand the marvels as well as the flaws of intuitive thought.”

Kahneman presented their new model of the mind to the general reader in Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), where he characterized the human mind as the interrelated operation of two systems of thought: System One, which is fast and automatic, including instincts, emotions, innate skills shared with animals, as well as learned associations and skills; and System Two, which is slow and deliberative and allows us to correct for the errors made by System One.

Lewis’s tale of this intellectual revolution begins in 1955 with the twenty-one-year-old Kahneman devising personality tests for the Israeli army and discovering that optimal accuracy could be attained by devising tests that removed, as far as possible, the gut feelings of the tester. The testers were employing “System One” intuitions that skewed their judgment and could be avoided if tests were devised and implemented in ways that disallowed any role for individual judgment and bias. This is an especially captivating episode for Lewis, since his best-selling book, Moneyball (2003), told the analogous tale of Billy Beane, general manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team, who used new forms of data analytics to override the intuitive judgments of baseball scouts in picking players.

The Undoing Project also applauds the story of the psychologist Lewis Goldberg, a colleague of Kahneman and Tversky in their days in Eugene, Oregon, who discovered that a simple algorithm could more accurately diagnose cancer than highly trained experts who were biased by their emotions and faulty intuitions. Algorithms—fixed rules for processing data—unlike the often difficult, emotional human protagonists of the book, are its uncomplicated heroes, quietly correcting for the subtle but consequential flaws in human thought.

The most influential of Kahneman and Tversky’s discoveries, however, is “prospect theory,” since this has provided the most important basis of the “biases and heuristics” approach of the new behavioral sciences. They looked at the way in which people make decisions under conditions of uncertainty and found that their behavior violated expected utility theory—a fundamental assumption of economic theory that holds that decision-makers reason instrumentally about how to maximize their gains. Kahneman and Tversky realized that they were not observing a random series of errors that occur when people attempted to do this. Rather, they identified a dozen “systematic violations of the axioms of rationality in choices between gambles.” These systematic errors make human irrationality predictable. [Continue reading…]

Wonders of the deep ocean

The New York Times reports: One of the great treasures in ocean preserves is the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, established in 2009 and expanded in 2014 to cover about 370,000 square miles.

That’s a lot of water to explore, and this year the research vessel Okeanos Explorer has been doing just that, collecting data and videos on the ocean and some of the astonishing creatures that live there.

The ship is operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which studies oceans and climate change, among other subjects. Scientists on board the most recent cruise — southwest of Hawaii — used a remotely operated vehicle, the Deep Discoverer, which can descend almost 20,000 feet, to take video of remarkable creatures like the deep water siphonophore. [Continue reading…]

Boston public schools map switch aims to amend 500 years of distortion

The Guardian reports: When Boston public schools introduced a new standard map of the world this week, some young students’ felt their jaws drop. In an instant, their view of the world had changed.

The USA was small. Europe too had suddenly shrunk. Africa and South America appeared narrower but also much larger than usual. And what had happened to Alaska?

In an age of “fake news” and “alternative facts”, city authorities are confident their new map offers something closer to the geographical truth than that of traditional school maps, and hope it can serve an example to schools across the nation and even the world.

For almost 500 years, the Mercator projection has been the norm for maps of the world, ubiquitous in atlases, pinned on peeling school walls.

Gerardus Mercator, a renowned Flemish cartographer, devised his map in 1569, principally to aid navigation along colonial trade routes by drawing straight lines across the oceans. An exaggeration of the whole northern hemisphere, his depiction made North America and Europe bigger than South America and Africa. He also placed western Europe in the middle of his map.

Mercator’s distortions affect continents as well as nations. For example, South America is made to look about the same size as Europe, when in fact it is almost twice as large, and Greenland looks roughly the size of Africa when it is actually about 14 times smaller. Alaska looks bigger than Mexico and Germany is in the middle of the picture, not to the north – because Mercator moved the equator.

Three days ago, Boston’s public schools began phasing in the lesser-known Peters projection, which cuts the US, Britain and the rest of Europe down to size. Teachers put contrasting maps of the world side by side and let the students study them. [Continue reading…]

‘I didn’t know you could have emotions out loud’

Laura Collins-Hughes writes: Stephan Wolfert was drunk when he hopped off an Amtrak train somewhere in Montana, toting a rucksack of clothes and a cooler stocked with ice, peanut butter, bread and Miller High Life — bottles, not cans. It was 1991, he was 24, and he had recently seen his best friend fatally wounded in a military training exercise.

His mind in need of a salve, he went to a play: “Richard III,” the story of a king who was also a soldier. In Shakespeare’s words, he heard an echo of his own experience, and though he had been raised to believe that being a tough guy was the only way to be a man, something cracked open inside him.

“I was sobbing,” Mr. Wolfert, now 50 and an actor, said recently over coffee in Chelsea. “I didn’t know you could have emotions out loud.”

That road-to-Damascus moment — not coming to Jesus, but coming to Shakespeare — is part of the story that Mr. Wolfert tells in his solo show, “Cry Havoc!,” which starts performances Wednesday, March 15, at the New Ohio Theater. Taking its title from Mark Antony’s speech over the slain Caesar in “Julius Caesar,” it intercuts Mr. Wolfert’s own memories with text borrowed from Shakespeare. Decoupling those lines from their plays, Mr. Wolfert uses them to explore strength and duty, bravery and trauma, examining what it is to be in the military and what it is to carry that experience back into civilian life. [Continue reading…]

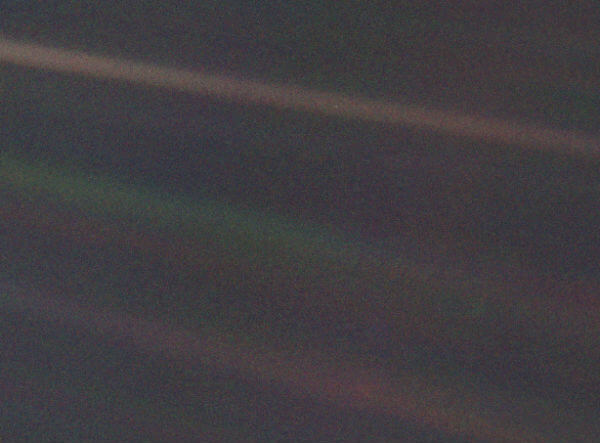

When Earth became a ‘mote of dust’

Shannon Stirone writes: We glimpsed Earth’s curvature in 1946, via a repurposed German V-2 rocket that flew 65 miles above the surface. Year-by-year, we climbed a little higher, engineering a means to comprehend the magnitude of our home.

In 1968, Apollo 8 lunar module pilot William Anders captured the iconic Earthrise photo. We contemplated the beauty of our home.

But on Valentine’s Day 27 years ago, Voyager 1, from 4 billion miles away, took one final picture before switching off its camera forever. In the image, Earth, Carl Sagan said, was merely “a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.” So we pondered the insignificance of our home. The image inspired Sagan to write his book “The Pale Blue Dot,” and it continues to cripple human grandiosity. [Continue reading…]

Was the first song a lullaby?

Tom Jacobs writes: Why do humans play, and listen, to music? The question has long baffled evolutionary theorists. Some suggest it had its origins in courtship rituals, while others contend it had (and has) a unique ability to bond people together to work toward a common goal.

Now, a couple of Harvard University researchers have proposed a new concept: They argue that the earliest music — and perhaps the prototype for everything from Bach to rap — may just have been the songs mothers sing to their infants.

Maybe the first musical genre wasn’t the love song, but rather the lullaby.

“The evolution of music must be a complex, multi-step process, with different features developing for different reasons,” says Samuel Mehr, who co-authored the paper with psychologist Max Krasnow. “Our theory raises the possibility that infant-directed song is the starting point for all that.”

Mothers vocalize to their babies “across many, if not all, cultures,” the researches note in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior. Its ubiquity suggests this activity plays a positive role in the parent-child relationship, presumably soothing infants by proving that someone is there and paying attention to them. [Continue reading…]

Newfound 3.77-billion-year-old fossils could be earliest evidence of life on Earth

The Washington Post reports: Tiny, tubular structures uncovered in ancient Canadian rocks could be remnants of some of the earliest life on Earth, scientists say.

The straw-shaped “microfossils,” narrower than the width of a human hair and invisible to the naked eye, are believed to come from ancient microbes, according to a new study in the journal Nature. Scientists debate the age of the specimens, but the authors’ youngest estimate — 3.77 billion years — would make these fossils the oldest ever found.

Claims of ancient fossils are always contentious. Rocks as old as the ones in the new study rarely survive the weathering, erosion, subduction and deformation of our geologically active Earth. Any signs of life in the rocks that do survive are difficult to distinguish, let alone prove. Other researchers in the field expressed skepticism about whether the structures were really fossils, and whether the rocks that contain them are as old as the study authors say.

But the scientists behind the new finding believe their analysis should hold up to scrutiny. In addition to structures that look like fossil microbes, the rocks contain a cocktail of chemical compounds they say is almost certainly the result of biological processes. [Continue reading…]

People can’t think straight

Elizabeth Kolbert writes: In 1975, researchers at Stanford invited a group of undergraduates to take part in a study about suicide. They were presented with pairs of suicide notes. In each pair, one note had been composed by a random individual, the other by a person who had subsequently taken his own life. The students were then asked to distinguish between the genuine notes and the fake ones.

Some students discovered that they had a genius for the task. Out of twenty-five pairs of notes, they correctly identified the real one twenty-four times. Others discovered that they were hopeless. They identified the real note in only ten instances.

As is often the case with psychological studies, the whole setup was a put-on. Though half the notes were indeed genuine — they’d been obtained from the Los Angeles County coroner’s office — the scores were fictitious. The students who’d been told they were almost always right were, on average, no more discerning than those who had been told they were mostly wrong.

In the second phase of the study, the deception was revealed. The students were told that the real point of the experiment was to gauge their responses to thinking they were right or wrong. (This, it turned out, was also a deception.) Finally, the students were asked to estimate how many suicide notes they had actually categorized correctly, and how many they thought an average student would get right. At this point, something curious happened. The students in the high-score group said that they thought they had, in fact, done quite well — significantly better than the average student — even though, as they’d just been told, they had zero grounds for believing this. Conversely, those who’d been assigned to the low-score group said that they thought they had done significantly worse than the average student — a conclusion that was equally unfounded.

“Once formed,” the researchers observed dryly, “impressions are remarkably perseverant.” [Continue reading…]

Bees learn to play golf and show off how clever they really are

New Scientist reports: It’s a hole in one! Bumblebees have learned to push a ball into a hole to get a reward, stretching what was thought possible for small-brained creatures.

Plenty of previous studies have shown that bees are no bumbling fools, but these have generally involved activities that are somewhat similar to their natural foraging behaviour.

For example, bees were able to learn to pull a string to reach an artificial flower containing sugar solution. Bees sometimes have to pull parts of flowers to access nectar, so this isn’t too alien to them.

So while these tasks might seem complex, they don’t really show a deeper level of learning, says Olli Loukola at Queen Mary University of London, an author of that study.

Loukola and his team decided the next challenge was whether bees could learn to move an object that was not attached to the reward.

They built a circular platform with a small hole in the centre filled with sugar solution, into which bees had to move a ball to get a reward. A researcher showed them how to do this by using a plastic bee on a stick to push the ball.

The researchers then took three groups of other bees and trained them in different ways. One group observed a previously trained bee solving the task; another was shown the ball moving into the hole, pulled by a hidden magnet; and a third group was given no demonstration, but was shown the ball already in the hole containing the reward.

The bees then did the task themselves. Those that had watched other bees do it were most successful and took less time than those in the other groups to solve the task. Bees given the magnetic demonstration were also more successful than those not given one. [Continue reading…]

Low-status chimps revealed as trendsetters

Science News reports: Chimps with little social status influence their comrades’ behavior to a surprising extent, a new study suggests.

In groups of captive chimps, a method for snagging food from a box spread among many individuals who saw a low-ranking female peer demonstrate the technique, say primatologist Stuart Watson of the University of St. Andrews in Fife, Scotland, and colleagues. But in other groups where an alpha male introduced the same box-opening technique, relatively few chimps copied the behavior, the researchers report online February 7 in the American Journal of Primatology.

“I suspect that even wild chimpanzees are motivated to copy obviously rewarding behaviors of low-ranking individuals, but the limited spread of rewarding behaviors demonstrated by alpha males was quite surprising,” Watson says. Previous research has found that chimps in captivity more often copy rewarding behaviors of dominant versus lower-ranking group mates. The researchers don’t understand why in this case the high-ranking individuals weren’t copied as much. [Continue reading…]

That the world is not solid but made up of tiny particles is a very ancient insight

Carlo Rovelli writes: According to tradition, in the year 450 BCE, a man embarked on a 400-mile sea voyage from Miletus in Anatolia to Abdera in Thrace, fleeing a prosperous Greek city that was suddenly caught up in political turmoil. It was to be a crucial journey for the history of knowledge. The traveller’s name was Leucippus; little is known about his life, but his intellectual spirit proved indelible. He wrote the book The Great Cosmology, in which he advanced new ideas about the transient and permanent aspects of the world. On his arrival in Abdera, Leucippus founded a scientific and philosophical school, to which he soon affiliated a young disciple, Democritus, who cast a long shadow over the thought of all subsequent times.

Together, these two thinkers have built the majestic cathedral of ancient atomism. Leucippus was the teacher. Democritus, the great pupil who wrote dozens of works on every field of knowledge, was deeply venerated in antiquity, which was familiar with these works. ‘The most subtle of the Ancients,’ Seneca called him. ‘Who is there whom we can compare with him for the greatness, not merely of his genius, but also of his spirit?’ asks Cicero.

What Leucippus and Democritus had understood was that the world can be comprehended using reason. They had become convinced that the variety of natural phenomena must be attributable to something simple, and had tried to understand what this something might be. They had conceived of a kind of elementary substance from which everything was made. Anaximenes of Miletus had imagined this substance could compress and rarefy, thus transforming from one to another of the elements from which the world is constituted. It was a first germ of physics, rough and elementary, but in the right direction. An idea was needed, a great idea, a grand vision, to grasp the hidden order of the world. Leucippus and Democritus came up with this idea.

The idea of Democritus’s system is extremely simple: the entire universe is made up of a boundless space in which innumerable atoms run. Space is without limits; it has neither an above nor a below; it is without a centre or a boundary. Atoms have no qualities at all, apart from their shape. They have no weight, no colour, no taste. ‘Sweetness is opinion, bitterness is opinion; heat, cold and colour are opinion: in reality only atoms, and vacuum,’ said Democritus. Atoms are indivisible; they are the elementary grains of reality, which cannot be further subdivided, and everything is made of them. They move freely in space, colliding with one another; they hook on to and push and pull one another. Similar atoms attract one another and join.

This is the weave of the world. This is reality. Everything else is nothing but a by-product – random and accidental – of this movement, and this combining of atoms. The infinite variety of the substances of which the world is made derives solely from this combining of atoms. [Continue reading…]

The neurology for reaching a destination

Moheb Costandi writes: How do humans and other animals find their way from A to B? This apparently simple question has no easy answer. But after decades of extensive research, a picture of how the brain encodes space and enables us to navigate through it is beginning to emerge. Earlier, neuroscientists had found that the mammalian brain contains at least three different cell types, which cooperate to encode neural representations of an animal’s location and movements.

But that picture has just grown far more complex. New research now points to the existence of two more types of brain cells involved in spatial navigation — and suggests previously unrecognized neural mechanisms underlying the way mammals make their way about the world.Earlier work, performed in freely moving rodents, revealed that neurons called place cells fire when an animal is in a specific location. Another type — grid cells — activate periodically as an animal moves around. Finally, head direction cells fire when a mouse or rat moves in a particular direction. Together, these cells, which are located in and around a deep brain structure called the hippocampus, appear to encode an animal’s current location within its environment by tracking the distance and direction of its movements.

This process is fine for simply moving around, but it does not explain exactly how a traveler gets to a specific destination. The question of how the brain encodes the endpoint of a journey has remained unanswered. To investigate this, Ayelet Sarel of the Weismann Institute of Science in Israel and her colleagues trained three Egyptian fruit bats to fly in complicated paths and then land at a specific location where they could eat and rest. The researchers recorded the activity of a total of 309 hippocampal neurons with a wireless electrode array. About a third of these neurons exhibited the characteristics of place cells, each of them firing only when the bat was in a specific area of the large flight room. But the researchers also identified 58 cells that fired only when the bats were flying directly toward the landing site. [Continue reading…]

How diversity makes us smarter

Katherine W. Phillips writes: The first thing to acknowledge about diversity is that it can be difficult. In the U.S., where the dialogue of inclusion is relatively advanced, even the mention of the word “diversity” can lead to anxiety and conflict. Supreme Court justices disagree on the virtues of diversity and the means for achieving it. Corporations spend billions of dollars to attract and manage diversity both internally and externally, yet they still face discrimination lawsuits, and the leadership ranks of the business world remain predominantly white and male.

It is reasonable to ask what good diversity does us. Diversity of expertise confers benefits that are obvious — you would not think of building a new car without engineers, designers and quality-control experts — but what about social diversity? What good comes from diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation? Research has shown that social diversity in a group can cause discomfort, rougher interactions, a lack of trust, greater perceived interpersonal conflict, lower communication, less cohesion, more concern about disrespect, and other problems. So what is the upside?

The fact is that if you want to build teams or organizations capable of innovating, you need diversity. Diversity enhances creativity. It encourages the search for novel information and perspectives, leading to better decision making and problem solving. Diversity can improve the bottom line of companies and lead to unfettered discoveries and breakthrough innovations. Even simply being exposed to diversity can change the way you think. This is not just wishful thinking: it is the conclusion I draw from decades of research from organizational scientists, psychologists, sociologists, economists and demographers.

[Continue reading…]

Giant atoms could help unveil ‘dark matter’ and other cosmic secrets

By Diego A. Quiñones, University of Leeds

The universe is an astonishingly secretive place. Mysterious substances known as dark matter and dark energy account for some 95% of it. Despite huge effort to find out what they are, we simply don’t know.

We know dark matter exists because of the gravitational pull of galaxy clusters – the matter we can see in a cluster just isn’t enough to hold it together by gravity. So there must be some extra material there, made up by unknown particles that simply aren’t visible to us. Several candidate particles have already been proposed.

Scientists are trying to work out what these unknown particles are by looking at how they affect the ordinary matter we see around us. But so far it has proven difficult, so we know it interacts only weakly with normal matter at best. Now my colleague Benjamin Varcoe and I have come up with a new way to probe dark matter that may just prove successful: by using atoms that have been stretched to be 4,000 times larger than usual.