Offering the latest iteration of one of the cardinal truths that has supposedly become irrefutable over the last decade or so, Robert Fisk writes: “For every dead Isis member, we are creating three of four more.”

Through its hydra-like capacity to self-replicate, ISIS is apparently more contagious than Ebola and the method of transmission is martyr-producing U.S. airstrikes.

In anticipating the proliferation of violence in an expanding war against ISIS, Fisk seems more perturbed about what a “murderous bunch of gunmen” might do — those being private security contractors ostensibly destined to be “let loose” in Syria — than the apparently overstated capabilities of that other murderous bunch of gunmen who like to be known as Islamic State.

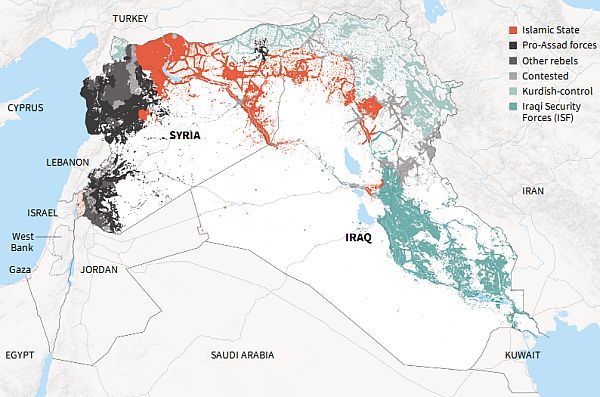

It remains to be seen whether ISIS will grow in the way Fisk anticipates. What has been widely reported is that so far this year, its rapid growth has been driven not by U.S. airstrikes; it has come from the group’s success in capturing territory and creating a rudimentary Islamic state.

The allure of the caliphate and battlefield victories seems greater than the allure of martyrdom. For these holy warriors the promise of an afterlife with virgins in heaven probably figures less in their imagination than the prospect of acquiring slaves in this life.

The glaring problem with the thesis that killing members of ISIS can only make the problem worse is that it discounts the gruesome toll each of these fighters continues to ratchet up.

Just as we might fear that with each ISIS member killed, another three or four might be created, we should include in our calculations those who have already become ISIS’s victims and those whose lives are in imminent danger.

When Kurdish fighters say that we either kill them or they will kill us, they are simply stating a fact.

In spite of this, an old argument that has in the past in different circumstances been relevant and valid is being pressed once again — the argument that our perspective on ISIS has been skewed by misleading rhetoric about terrorism.

This comes from Tomis Kapitan:

To put it bluntly, by stifling inquiry into causes, the rhetoric of “terror” actually increases the likelihood of terrorism. First, it magnifies the effect of terrorist actions by heightening the fear among the target population. If we demonize the terrorists, if we portray them as evil, irrational beings devoid of a moral sense, we amplify the fear and alarm generated by terrorist incidents, even when this is one of the political objectives of the perpetrators. In addition, stricter security measures often appear on the home front, including enhanced surveillance and an increasing militarization of local police.

Second, those who succumb to the rhetoric contribute to the cycle of revenge and retaliation by endorsing military actions that grievously harm the populations among whom terrorists live. The consequence is that civilians, those least protected, become the principle victims of “retaliation” or “counterterrorism.”

Having been desensitized by language, the willingness to risk civilian casualties becomes increasingly widespread. For example, according to a CBS/New York Times poll of 1216 Americans published on September 16, 2001, nearly 60 percent of those polled supported the use of military force against terrorists even if “many thousands of innocent civilians may be killed,” an echo of the view taken by Netanyahu in his book.

Third, a violent response is likely to stiffen the resolve of those from whose ranks terrorists have emerged, leading them to regard their foes as people who cannot be reasoned with, as people who, because they avail themselves so readily of the rhetoric of “terror,” know only the language of force. As long as groups perceive themselves to be victims of intolerable injustices and view their oppressors as unwilling to arrive at an acceptable compromise, they are likely to answer violence with more violence. Their reaction might be strategic, if directed against civilians to achieve a particular political objective, but, with the oppression unabated, it increasingly becomes the retaliatory violence of despair and revenge.

There’s a problem with on the one hand attempting to deconstruct the terror rhetoric while at the same time persisting in the use of the category: terrorists.

To do this is to sustain the notion that, for instance, “Hamas, Hezbollah or ISIS” — a grouping Kapitan employs — have a sufficient number of common features that we can start making generalizations about better ways to “tackle terrorism” and then assume they could be employed in each instance.

The most commonly promoted alternative to using military force to combat terrorism is negotiation. Indeed, many governments directly or indirectly talk to Hamas and Hezbollah, so why isn’t anyone talking to ISIS?

An American ex-servicemen who has joined the ranks of the Syrian Kurdish YPG and is now fighting against ISIS provides a blunt answer:

“You can’t talk to people like that. There’s no reasoning at all. There’s a war and we have to eliminate them.”

Obviously, those who argue that violence begets violence will reject this soldier’s position. Some may argue that he is himself a victim of the terror rhetoric which has demonized ISIS.

Perhaps. But if this argument against war is to acquire more weight, then those who imply that there are viable alternatives need to spell out in greater detail what those alternatives are.

The only willingness to negotiate displayed by ISIS up to this point has been on the terms for releasing hostages. If that’s the extent of its flexibility, it’s not worth much.

But let’s imagine, just for the sake of argument, what the terms might be for political negotiations.

Can we imagine some kind of compromise caliphate? Sharia with due process? No female under the age of 18 can be enslaved? No one can be decapitated without first receiving an anesthetic?

Maybe if the negotiations went particularly well, ISIS would be willing to make a major gesture of conciliation and reach out to the West by implementing an outright ban on crucifixions.

There is of course another alternative approach for dealing, or to be more precise, not dealing with ISIS — a common ground that unites a significant number of Americans across the political spectrum.

It’s an approach that’s voiced more freely on the Right than the Left since it expresses a cold-blooded nationalism. It simply says: ISIS poses a threat to Syrians, Kurds, Iraqis and others in the Middle East. It poses little threat to Americans. Why should we care? Why should we get involved? It’s not our problem.

In its progressively tempered form, this sentiment gains a little warmth and says: we do care, but as much as we get involved, we’re sure to make things worse. Sorry, we feel your pain, but look at the mess we’ve already created in the Middle East. You’re really better off without our “help.”

I don’t believe there are any avenues available to negotiate with ISIS, but neither do I think it can be ignored. If its growth was to remain unchecked, a region already deeply fragmented will only become more violent.

The Kurds on the frontlines fighting against ISIS deserve America’s full support, but Obama’s war against ISIS thus far lacks an real strategic foundation.

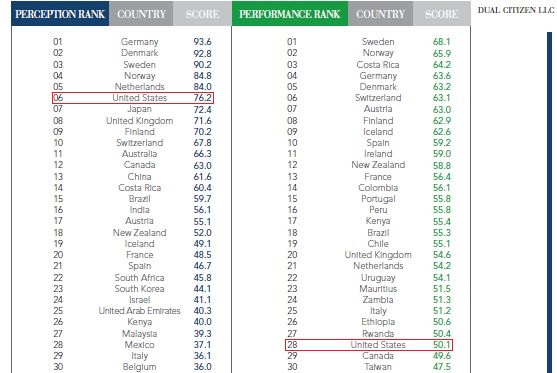

The growth of ISIS stems as much as anything else from a pernicious cycle of American engagement with the world, oscillating between efforts to exercise too much control, followed by periods of withdrawal. Either America is in charge or it won’t play.

At some point America needs to outgrow this cycle of domination and isolation, acting as one nation among many to pursue goals that serve global interests. America can’t save the world but neither should it try to escape from it.