(Updated below)

In the second article on its series on Top Secret America, the Washington Post looks at “National Security Inc” where the boundaries of government have dissolved in a defense-intelligence-corporate world.

To illustrate the way this world operates in the post-9/11 era, Dana Priest and William Arkin focus on one of the lead corporations: General Dynamics.

The evolution of General Dynamics was based on one simple strategy: Follow the money.

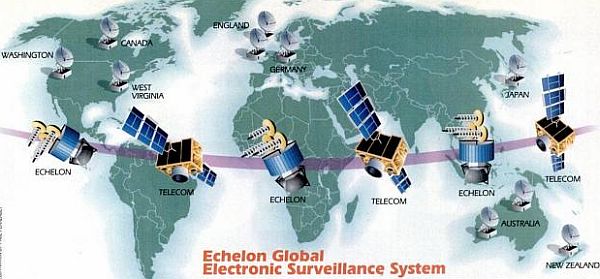

The company embraced the emerging intelligence-driven style of warfare. It developed small-target identification systems and equipment that could intercept an insurgent’s cellphone and laptop communications. It found ways to sort the billions of data points collected by intelligence agencies into piles of information that a single person could analyze.

It also began gobbling up smaller companies that could help it dominate the new intelligence landscape, just as its competitors were doing. Between 2001 and 2010, the company acquired 11 firms specializing in satellites, signals and geospatial intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, technology integration and imagery.

On Sept. 11, 2001, General Dynamics was working with nine intelligence organizations. Now it has contracts with all 16. Its employees fill the halls of the NSA and DHS. The corporation was paid hundreds of millions of dollars to set up and manage DHS’s new offices in 2003, including its National Operations Center, Office of Intelligence and Analysis and Office of Security. Its employees do everything from deciding which threats to investigate to answering phones.

General Dynamics’ bottom line reflects its successful transformation. It also reflects how much the U.S. government – the firm’s largest customer by far – has paid the company beyond what it costs to do the work, which is, after all, the goal of every profit-making corporation.

The company reported $31.9 billion in revenue in 2009, up from $10.4 billion in 2000. Its workforce has more than doubled in that time, from 43,300 to 91,700 employees, according to the company.

Revenue from General Dynamics’ intelligence- and information-related divisions, where the majority of its top-secret work is done, climbed to $10 billion in the second quarter of 2009, up from $2.4 billion in 2000, accounting for 34 percent of its overall revenue last year.

The company’s profitability is on display in its Falls Church headquarters. There’s a soaring, art-filled lobby, bistro meals served on china enameled with the General Dynamics logo and an auditorium with seven rows of white leather-upholstered seats, each with its own microphone and laptop docking station.

General Dynamics now has operations in every corner of the intelligence world. It helps counterintelligence operators and trains new analysts. It has a $600 million Air Force contract to intercept communications. It makes $1 billion a year keeping hackers out of U.S. computer networks and encrypting military communications. It even conducts information operations, the murky military art of trying to persuade foreigners to align their views with U.S. interests.

“The American intelligence community is an important market for our company,” said General Dynamics spokesman Kendell Pease. “Over time, we have tailored our organization to deliver affordable, best-of-breed products and services to meet those agencies’ unique requirements.”

In September 2009, General Dynamics won a $10 million contract from the U.S. Special Operations Command’s psychological operations unit to create Web sites to influence foreigners’ views of U.S. policy. To do that, the company hired writers, editors and designers to produce a set of daily news sites tailored to five regions of the world. They appear as regular news Web sites, with names such as “SETimes.com: The News and Views of Southeast Europe.” The first indication that they are run on behalf of the military comes at the bottom of the home page with the word “Disclaimer.” Only by clicking on that do you learn that “the Southeast European Times (SET) is a Web site sponsored by the United States European Command.”

What all of these contracts add up to: This year, General Dynamics’ overall revenue was $7.8 billion in the first quarter, Jay L. Johnson, the company’s chief executive and president, said at an earnings conference call in April. “We’ve hit the deck running in the first quarter,” he said, “and we’re on our way to another successful year.”

But here’s what’s remarkable about this description of General Dynamics: no mention of the way in which this company exemplifies in its governance the revolving door through which retired military officers and government officials cash in on their years of “public service.”

Nothing lubricates the wheels of defense commerce better than to have General Dynamics’ boardroom filled with retired generals and admirals:

Jay L. Johnson, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer — Retired Admiral, U.S. Navy. Chief of Naval Operations from 1996 to 2000.

George A. Joulwan, Director and Chairman, Compensation Committee — Retired General, U.S. Army. Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, from 1993 to 1997. Commander-in-Chief, Southern Command from 1990 to 1993.

Paul G. Kaminski, Director and Chairman, Finance and Benefit Plans Committee — Under Secretary of U.S. Department of Defense for Acquisition and Technology from 1994 to 1997.

John M. Keane, Director — Retired General, U.S. Army. Vice Chief of Staff of the Army from 1999 to 2003.

Lester L. Lyles, Director — Retired General, U.S. Air Force. Commander of the Air Force Materiel Command from 2000 to 2003. Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force from 1999 to 2000.

Robert Walmsley, Director — Retired Vice Admiral, Royal Navy. Chief of Defence Procurement for the United Kingdom Ministry of Defence from 1996 to 2003.

The Washington Post article ends with the suggestion that government officials can be enticed with baubles as modest as a free pen, but the key nodes in the corrupt government-corporate nexus are clearly at the highest levels where tax dollars get siphoned into private bank accounts by retired generals and former government officials who smugly regard the practice as the way Washington works.

Indeed it is — and it is the way capitalism corrupts democracy.

Update: A reader has drawn my attention to the significance of the Crown family (which has been a strong financial supporter of Barack Obama since the 2003), Henry Crown being a Chicago financier and one of the richest, but least known, men in the US who acquired General Dynamics in 1959. Crown’s grandson, James S Crown, is currently Lead Director and Chairman of GD and also a director of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Sara Lee Corporation.

Through the Crown family, GD has strong ties to the Israeli defense industry.

An article that appeared in Electronic Intifada in 2005 noted:

A 2003 press release of the General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems business unit in St. Petersburg, Florida also noted that it had formed “a strategic alliance with Aeronautics Defense Systems, Ltd.,” an Israeli firm based in Yavne. Aeronautics Defense Systems Ltd. is the firm that developed the Unmanned Multi-Application System (UMASa) aerial surveillance tool which the Israeli military uses to “provide a real-time ‘bird’s eye view’ of the surveillance area to combatant commanders and airborne command posts.” According to Israeli Deputy Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, the agreement between General Dynamics and Aeronautics Defense Systems to bring together “both companies’ state-of-the art technologies in defense and homeland security” was “additional proof of the technological and commercial benefits that alliances between industries from the U.S. and Israel can produce.”

From its investments in Pentagon war contractors like General Dynamics and U.S. real estate, the Crown family has accumulated a family fortune of $3.6 billion, according to a recent Forbes magazine estimate. A portion of the Crown family’s surplus wealth was apparently recently shifted to Brandeis University in Massachusetts in order to establish the “Crown Center for Middle East Studies.”

According to the February 27, 2005 issue of the Jerusalem Post, “the center’s major funder, the Crown family of Chicago, is well-known for its support of sectarian Jewish causes, including the Ida Crown Jewish Academy, an orthodox day school in Chicago.” In addition to being a member of the General Dynamics corporate board, for instance, Lester Crown is a member of the board of The Jerusalem Foundation Inc. and a a member of Tel Aviv University’s Board of Governors. Lester Crown has also been actively involved with the American Jewish Committee and is a member of the advisory board of Medis Technologies, a joint venture business partner of Israel Aircraft Industries Ltd.

In January 2008, during the presidential election, Lester Crown (father of James Crown) wrote a “Dear friends” letter to a large number of Jewish voters, titled “Barack Obama on Israel as a Jewish State.”

“While my involvement in politics is motivated by a variety of issues, there is one issue that is fundamental: My deep commitment to Israel and to a strong U.S.-Israel relationship that strengthens both Israel’s security and its efforts to seek peace,” Crown wrote. “I am writing to share with you my confidence that Senator Barack Obama’s stellar record on Israel gives me great comfort that, as President, he will be the friend to Israel that we all want to see in the White House – stalwart in his defense of Israel’s security, and committed to helping Israel achieve peace with its neighbors.”

Crown’s confidence in the reliability of his investment in Obama appears to have been well-founded.

Professor John Mearsheimer from the University of Chicago, includes Crown among what he calls “new Afrikaners, who will support Israel even if it is an apartheid state. These are individuals who will back Israel no matter what it does, because they have blind loyalty to the Jewish state.”

It is just two months since the newly-created

It is just two months since the newly-created