A letter from Afghanistan that every American must read

By Paul Woodward, War in Context, October 27, 2009

“… I have lost understanding of and confidence in the strategic purposes of the United States’ presence in Afghanistan. I have doubts and reservations about our current strategy and planned future strategy, but my resignation is based not upon how we are pursuing this war, but why and to what end. To put simply: I fail to see the value or the worth in continued U.S. casualties or expenditures or resources in support of the Afghan government in what is, truly, a 35-year old civil war.” From Matthew P Hoh, Senior Civilian Representative, Zabul Province, Afghanistan, in his letter of resignation to the State Department.

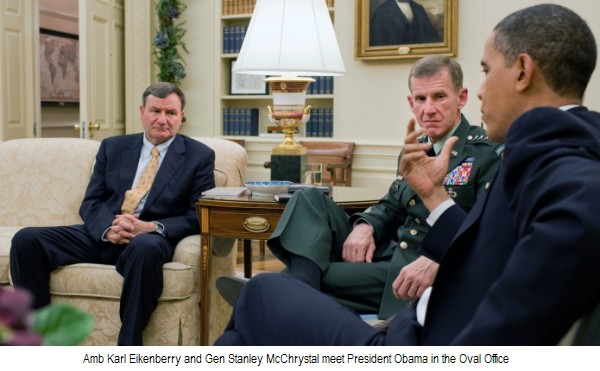

For weeks, President Obama and his advisers in the White House and from the Pentagon have been wrestling over the formulation of a revised strategy for Afghanistan. Central to that debate has been the question of how to respond to Gen Stanley McChrystal’s request for tens of thousands more American troops.

But perhaps the most important question — one which the president and his advisers have no doubt studiously avoided asking — is whether this war is worth fighting.

Matthew Hoh, a former US Marine captain who fought in Iraq, and who later served as a civilian State Department representative in the Zabul province of Afghanistan, in a letter of resignation submitted in early September, provided a definitive statement on the war’s failure — in its conception, its execution, and its aims. Rarely, if ever, has such an damning indictment of this war been so clearly and powerfully expressed.

The Washington Post reported:

The reaction to Hoh’s letter was immediate. Senior U.S. officials, concerned that they would lose an outstanding officer and perhaps gain a prominent critic, appealed to him to stay.

U.S. Ambassador Karl W. Eikenberry brought him to Kabul and offered him a job on his senior embassy staff. Hoh declined. From there, he was flown home for a face-to-face meeting with Richard C. Holbrooke, the administration’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“We took his letter very seriously, because he was a good officer,” Holbrooke said in an interview. “We all thought that given how serious his letter was, how much commitment there was, and his prior track record, we should pay close attention to him.”

The Post has published Hoh’s letter in a printable format [PDF] which is likely to result in the whole letter not being widely read. In order to encourage readers to absorb the full force of this testimony, I’ve reproduced the letter in full below — the only place (as far as I’m aware) that it can currently be found on the web in a user-friendly format.

“We are spending ourselves into oblivion”

By Matthew P Hoh, Senior Civilian Representative, Zabul Province, Afghanistan, September 10, 2009

Dear Ambassador Powell,

It is with great regret and disappointment I submit my resignation from my appointment as a Political Officer in the Foreign Service and my post as the Senior Civilian Representative for the U.S. Government in Zabul Province. I have served six of the previous ten years in service to our country overseas, to include deployment as a U.S. Marine officer and Department of Defense civilian in the Euphrates and Tigris River Valleys of Iraq in 2004-2005 and 2006-2007. I did not enter into this position lightly or with any undue expectations nor did I believe my assignment would be without sacrifice hardship or difficulty. However, in the course of my five months of service in Afghanistan, in both Regional Commands East and South, I have lost understanding of and confidence in the strategic purposes of the United States’ presence in Afghanistan. I have doubts and reservations about our current strategy and planned future strategy, but my resignation is based not upon how we are pursuing this war, but why and to what end. To put simply: I fail to see the value or the worth in continued U.S. casualties or expenditures or resources in support of the Afghan government in what is, truly, a 35-year old civil war.

This fall will mark the eighth year of U.S. combat, governance and development operations within Afghanistan. Next fall, the United States’ occupation will equal in length the Soviet Union’s own physical involvement in Afghanistan. Like the Soviets, we continue to secure and bolster a failing state, while encouraging an ideology and system of government unknown and unwanted by its people.

If the history or Afghanistan is one great stage play, the United States is no more than a supporting actor, among several previously, in a tragedy that not only pits tribes, valleys, clans, villages and families against one another, but, from at least the end of King Zahir Shah’s reign, has violently and savagely pitted the urban, secular, educated and modem of Afghanistan against the rural, religious, illiterate and traditional. It is this latter group that composes and supports the Pashtun insurgency. The Pashtun insurgency, which is composed of multiple, seemingly infinite, local groups, is fed by what is perceived by the Pashtun people as a continued and sustained assault, going back centuries, on Pashtun land, culture, traditions and religion by internal and external enemies. The U.S. and NATO presence and operations in Pashtun valleys and villages, as well as Afghan army and police units that are led and composed of non-Pashtun soldiers and police, provide an occupation force against which the insurgency is justified. In both RC East and South, I have observed that the bulk of the insurgency fights not for the white banner of the Taliban, but rather against the presence of foreign soldiers and taxes imposed by an unrepresentative government in Kabul.

The United States military presence in Afghanistan greatly contributes to the legitimacy and strategic message of the Pashtun insurgency. In a like manner our backing of the Afghan government in its current form continues to distance the government from the people. The Afghan government’s failings, particularly when weighed against the sacrifice of American lives and dollars, appear legion and metastatic:

• Glaring corruption and unabashed graft;

• A President whose confidants and chief advisers comprise drug lords and war crimes villains, who mock our own rule of law and counternarcotics efforts;

• A system of provincial and district leaders constituted of local power brokers, opportunists and strongmen allied to the United States solely for, and limited by, the value of our USAID and CERP contracts and whose own political and economic interests stand nothing to gain from any positive or genuine attempts at reconciliation; and

• The recent election process dominated by fraud and discredited by low voter turnout, which has created an enormous victory for our enemy who now claims a popular boycott and will call into question worldwide our government’s military, economic and diplomatic support for an invalid and illegitimate Afghan government.

Our support for this kind of government, coupled with a misunderstanding of the insurgency’s true nature, reminds me horribly of our involvement with South Vietnam; an unpopular and corrupt government we backed at the expense of our Nation’s own internal peace, against an insurgency whose nationalism we arrogantly and ignorantly mistook as a rival to our own Cold War ideology.

I find specious the reasons we ask for bloodshed and sacrifice from our young men and women in Afghanistan. If honest, our stated strategy of securing Afghanistan to prevent al-Qaeda resurgence or regrouping would require us to additionally invade and occupy western Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, etc. Our presence in Afghanistan has only increased destabilization and insurgency in Pakistan where we rightly fear a toppled or weakened Pakistani government may lose control of nuclear weapons. However, again, to follow the logic of our stated goals we should garrison Pakistan, not Afghanistan. More so, the September 11th attacks, as well as the Madrid and London bombings, were primarily planned and organized in Western Europe; a point that highlights the threat is not one tied to traditional geographic or political boundaries. Finally, if our concern is for a failed state crippled by corruption and poverty and under assault from criminal and drug lords, then if we bear our military and financial contributions to Afghanistan, we must reevaluate our commitment to and involvement in Mexico.

Eight years into war, no nation has ever known a more dedicated, well trained, experienced and disciplined military as the U.S. Armed Forces. I do not believe any military force has ever been tasked with such a complex, opaque and Sisyphean mission as the U.S. military has received in Afghanistan. The tactical proficiency and performance of our Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Marines is unmatched and unquestioned. However, this is not the European or Pacific theaters of World War II, but rather is a war for which our leaders, uniformed, civilian and elected, have inadequately prepared and resourced our men and women. Our forces, devoted and faithful, have committed to conflict in an indefinite and unplanned manner that has become a cavalier, politically expedient and Pollyannaish misadventure. Similarly, the United States has a dedicated and talented cadre of civilians, both U.S. government employees and contractors, who believe in and sacrifice for their mission, but have been ineffectually trained and led with guidance and intent shaped more by the political climate in Washington, D.C. than in Afghan cities, villages, mountains and valleys.

“We are spending ourselves into oblivion” a very talented and intelligent commander, one of America’s best, briefs every visitor, staff delegation and senior officer. We are mortgaging our Nation’s economy on a war, which, even with increased commitment, will remain a draw for years to come. Success and victory, whatever they may be, will be realized not in years, after billions more spent, but in decades and generations. The United States does not enjoy a national treasury for such success and victory.

I realize the emotion and tone of my letter and ask you excuse any ill temper. I trust you understand the nature of this war and the sacrifices made by so many thousands of families who have been separated from loved ones deployed in defense of our Nation and whose homes bear the fractures, upheavals and scars of multiple and compounded deployments. Thousands of our men and women have returned home with physical and mental wounds, some that will never heal or will only worsen with time. The dead return only in bodily form to be received by families who must be reassured their dead have sacrificed for a purpose worthy of futures lost, love vanished, and promised dreams unkept. I have lost confidence such assurances can anymore be made. As such, l submit my resignation.

Sincerely,

Matthew P. Hoh

Senior Civilian Representative

Zabul Province, Afghanistan

cc:

Mr. Frank Ruggiero

Ms. Dawn Liberi

Ambassador Anthony Wayne

Ambassador Karl Eikenberry

This letter was addressed to:

Ambassador Nancy J. Powell

Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Human Resources

U.S. Department of State

2201 C Street NW

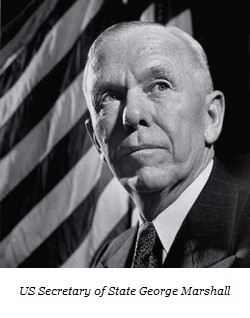

In early February of 2006, I submitted a book proposal about the wartime relationship between Generals George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower to a group of New York publishers. I had worked on the proposal for nine months and believed it would garner significant interest. Two weeks after the submission, I received my first response — from a senior editor at a major New York publishing firm. He was uncomfortable with the proposal: “Wasn’t Marshall an anti-Semite?” he asked. I’d heard this claim before, but I was still shocked by the question. For me, George Marshall was an icon: the one officer who, more than any other, was responsible for the American victory in World War Two. He was the most important soldier of his generation — and a man of great moral and physical courage.

In early February of 2006, I submitted a book proposal about the wartime relationship between Generals George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower to a group of New York publishers. I had worked on the proposal for nine months and believed it would garner significant interest. Two weeks after the submission, I received my first response — from a senior editor at a major New York publishing firm. He was uncomfortable with the proposal: “Wasn’t Marshall an anti-Semite?” he asked. I’d heard this claim before, but I was still shocked by the question. For me, George Marshall was an icon: the one officer who, more than any other, was responsible for the American victory in World War Two. He was the most important soldier of his generation — and a man of great moral and physical courage.