In a review of Noam Chomsky latest book, Who Rules the World?, Kenneth Roth writes: Chomsky’s book is not an objective account of the past. It is a polemic designed to awaken Americans from complacency. America, in his view, must be reined in, and he makes the case with verve and self-confident assertion, even if factual details are sometimes selective or scarce.

Yet Who Rules the World? is also an infuriating book because it is so partisan that it leaves the reader convinced not of his insights but of the need to hear the other side. It doesn’t help that the book is a collection of previously published essays with no effort to trim the repetitive points that pop up in chapter after chapter. Nor was much attempt made to update earlier chapters in light of later events. The Iranian nuclear accord and the Paris climate deal are mentioned only toward the end of the book, even though the issues of Iran’s nuclear program and climate change appear in earlier chapters.

At times Chomsky’s book suffers from simple sloppiness. For example, he reports that “the Obama administration considered reviving military commissions” on Guantánamo when in fact these commissions have been operating there for most of President Barack Obama’s eight years in office. And in certain places it is simply confused, as when Chomsky quotes from a review by Jessica Mathews in these pages and implies that she subscribes to the view that America advances “universal principles” rather than “national interests,” when in fact she was criticizing that perspective as part of her negative review of a book by Bret Stephens.

In some respects, Chomsky’s preoccupation with American power seems out of date because the limits of American power have become so apparent. When we ask “Who rules the world?” and take account of Syrian atrocities, the emergence of the Islamic State, or the mass displacement of refugees, the answer is less likely to be the American superpower than no one. Obama’s foreign policy has been far more about recognizing the limits of US military power than the exercise of that power, but this merits barely a mention by Chomsky. His America is the one of military adventure — the Vietnam War, the Bay of Pigs, the Central American conflicts of the 1980s, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the potentially suicidal recklessness of the nuclear arms race.

Chomsky’s selective use of history limits his persuasiveness. He blames Middle East turmoil, for example, largely on the World War I-era Sykes-Picot agreement that divided the former Ottoman Empire among British and French colonial powers. He’s right that the borders were drawn arbitrarily, and that the multiethnic and multiconfessional states they produced are difficult to govern, but is that really an adequate explanation of the region’s current turmoil? President George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq fits his thesis of American malevolence, and the terrible human costs of the war get mentioned, but Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s decision to fight his country’s civil war by targeting civilians in opposition-held areas, killing hundreds of thousands and setting off the flight of several million refugees, does not. Nor does Russia’s decision to back Assad’s murderous shredding of the Geneva Conventions, since Chomsky’s focus is America’s contribution to global suffering, not Vladimir Putin’s.

Still, it is useful to read Chomsky because he does undermine the facile if comforting myths that are often used to justify US action abroad — the distinction between, as Chomsky puts it, “what we stand for” and “what we do.” His views are held not only by American critics on the left but also by many people around the world who are more likely to think of themselves as targeted rather than protected by US military power. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: U.S. exceptionalism

Why sorry isn’t enough after deadly hospital airstrike

Neil Macdonald writes: Mark Toner, the suave U.S. State Department spokesman, arrived in the briefing room Monday unprepared for what was coming.

Two days earlier, American airstrikes had obliterated a hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, operated by Doctors Without Borders. The attack killed 22 people, including several staff members.

By the time Toner took to his podium, U.S. military officials had already given conflicting versions of what had happened.

But the underlying message was the same: There had been Taliban militants near the hospital and, in defence of American and Afghan troops, an American airstrike had inadvertently and tragically killed civilians.

Clearly, in Toner’s mind, the attack was a Pentagon matter. His briefing book contained some words of condolence to families of the dead, and evidently not much more.

Then Matt Lee of the Associated Press asked a question.

Lee began by reading aloud a State Department statement issued in August 2014 after an Israeli missile attack killed several people at a UN school in Gaza.

“The United States is appalled by today’s disgraceful shelling outside an UNRWA school,” said the State Department at the time. “The coordinates of the school, like all UN facilities in Gaza, have been repeatedly communicated to the Israeli Defence Forces.”

The statement continued: “The suspicion that militants are operating nearby does not justify strikes that put at risk the lives of so many innocent civilians.”

So, asked Lee, does that sentence about the presence of militants not justifying strikes that endanger innocent civilians stand as U.S. government policy?

Toner, having seen where this was going, dived into his official condolences, but quickly ran out of prepared messages.

He looked up: “Uh, you know, these are difficult situations, uh, it was I think … an active combat zone.”

Lee wasn’t going to be put off.

U.S. forces in Afghanistan, he told Toner, had been given the coordinates of the hospital, “much as the IDF had been given the coordinates of the school in Rafah” in Gaza.

Toner evaded: “I think it’s safe to say that, you know, this attack, this bombing, was not intentional,” he replied, asking for “a pass” until the investigations by U.S. agencies are completed.

Lee then expertly closed the trap.

After the “disgraceful” Israeli attack, he pointed out, the State Department declared itself “appalled” even before any investigation had begun.

“So. Can you say now … that this shelling of this hospital was disgraceful and appalling?”

At that, Toner just gave up, and re-read the condolence lines. [Continue reading…]

Tom Engelhardt: The age of impunity

An exceptional decline for the exceptional country?

By Tom Engelhardt

For America’s national security state, this is the age of impunity. Nothing it does — torture, kidnapping, assassination, illegal surveillance, you name it — will ever be brought to court. For none of its beyond-the-boundaries acts will anyone be held accountable. The only crimes that can now be committed in official Washington are by those foolish enough to believe that a government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from this earth. I’m speaking of the various whistleblowers and leakers who have had an urge to let Americans know what deeds and misdeeds their government is committing in their name but without their knowledge. They continue to pay a price in accountability for their acts that should, by comparison, stun us all.

As June ended, the New York Times front-paged an account of an act of corporate impunity that may, however, be unique in the post-9/11 era (though potentially a harbinger of things to come). In 2007, as journalist James Risen tells it, Daniel Carroll, the top manager in Iraq for the rent-a-gun company Blackwater, one of the warrior corporations that accompanied the U.S. military to war in the twenty-first century, threatened Jean Richter, a government investigator sent to Baghdad to look into accounts of corporate wrongdoing.

Here, according to Risen, is Richter’s version of what happened when he, another government investigator, and Carroll met to discuss Blackwater’s potential misdeeds in that war zone:

“Mr. Carroll said ‘that he could kill me at that very moment and no one could or would do anything about it as we were in Iraq,’ Mr. Richter wrote in a memo to senior State Department officials in Washington. He noted that Mr. Carroll had formerly served with Navy SEAL Team 6, an elite unit. ‘Mr. Carroll’s statement was made in a low, even tone of voice, his head was slightly lowered; his eyes were fixed on mine,’ Mr. Richter stated in his memo. ‘I took Mr. Carroll’s threat seriously. We were in a combat zone where things can happen quite unexpectedly, especially when issues involve potentially negative impacts on a lucrative security contract.’”

When officials at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, the largest in the world, heard what had happened, they acted promptly. They sided with the Blackwater manager, ordering Richter and the investigator who witnessed the scene out of the country (with their inquiry incomplete). And though a death threat against an American official might, under other circumstances, have led a CIA team or a set of special ops guys to snatch the culprit off the streets of Baghdad, deposit him on a Navy ship for interrogation, and then leave him idling in Guantanamo or in jail in the United States awaiting trial, in this case no further action was taken.

Power Centers But No Power to Act

Think of the response of those embassy officials as a get-out-of-jail-free pass in honor of a new age. For the various rent-a-gun companies, construction and supply outfits, and weapons makers that have been the beneficiaries of the wholesale privatization of American war since 9/11, impunity has become the new reality. Pull back the lens further and the same might be said more generally about America’s corporate sector and its financial outfits. There was, after all, no accountability for the economic meltdown of 2007-2008. Not a single significant figure went to jail for bringing the American economy to its knees. (And many such figures made out like proverbial bandits in the government bailout and revival of their businesses that followed.)

America’s rise as a superpower

In Der Spiegel, Hans Hoyng writes: “Sarajevo, 21st-century version.” This is how political scientist Anne-Marie Slaughter, the director of policy planning under former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, refers to what is currently brewing off the Chinese coast, where the territorial claims of several nations overlap.

The analogy to the period prior to the outbreak of World War I is striking. China, “the Germany of (that) time,” as American historian Robert Kagan puts it, is the emergent world power still seeking to define its role within the global community. At the same time, China is staking its claim to natural resources, intimidating its neighbors and developing massive naval power to secure its trade routes.

In taking these steps, China could easily become a rival to another world power, the United States of America, which would assume the role once played by Great Britain in this historical comparison. Just as the United Kingdom did at the time, the United States is now building alliances with its rival’s neighbors. And leaders in Beijing have responded to such attempts to encircle their country with a similar sense of outrage as that displayed by the German Reich.

The current crisis in the East China Sea illustrates once again that there are still lessons to be learned from World War I a century after it began and, upon closer inspection, that politicians on both sides are trying to avoid making the same mistakes. But the current crisis in East Asia diverges from the situation leading up to World War I in one important respect: There is currently no country able to assume the role once played by the United States, which, with its late entry into the war, decided its outcome and eventually outpaced both its winners and losers.

The US’s entry into the war in 1917 marked the beginning of its path to becoming a world power. In fact, according to historian Herfried Münkler, this was precisely the goal of some politicians in Washington. Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo, a son-in-law of President Woodrow Wilson, was already forging plans to replace the pound sterling with the dollar as the foremost international reserve currency.

But his father-in-law, a lawyer and political scientist, and America’s only president to enter politics after serving as the president of a university, had no such prosaic intentions. Wilson, the descendent of Scottish Presbyterians and a staunch idealist, and yet down-to-earth and in many respects, such as his racism, a son of the South, wanted to save the world and end war once and for all.

He failed, of course, with peace lasting only 20 years after World War I. Nevertheless, American politicians today justify military intervention with the same arguments Wilson used to convince the country to put an end to its isolation and intervene in Europe. [Continue reading…]

The fall of Falluja reveals the tragic futility of America’s strategy in the Middle East

Graham E. Fuller writes: When is a war “worth it?” It’s a timeless question that still begs a decisive response.

The debacle of Iraq has now drifted off the scope Americans’ attention — US troops are no longer dying there and new challenges beckon Washington elsewhere. Been there, done that. The American part of the war may be over, and we have grown weary hearing about it, but the Iraqi part of the war still continues. And with the recent and symbolic fall, again, of Falluja to al-Qa’ida and other jihadis we are forcefully reminded of the price that we paid in the American cleansing of Falluja ten years ago — for naught. Falluja, massively damaged, seems back to square one.

What about the Iraqis — was the war worth it for them? The figures are pretty well known by now — upwards of half a million Iraqis died, either in the violence of war or subsequent civil strife. That’s roughly equivalent to 5 million US citizens dying in a war. Add at least one million Iraqis displaced from their homes and villages, many now in exile — equivalent to ten million Americans displaced. Saddam was one of the most brutal dictators the world has seen in modern times, but one wonders–Iraqis must wonder — whether anything Saddam could have done could ever have remotely approached such human and structural devastation as the war. And the psychological damage — constant fear, death, mayhem, ongoing massive insecurity, anarchy and civil conflict –is not yet over.

Still, if you talk to some Iraqi Shi’a, the shift of power from the hands of a Sunni minority under a brutal dictator into the hands of the Shi’ite majority was a long term political godsend for them; they are today “better off” — at least politically, than before the war. But that’s a political abstraction.

Was it “worth it” to individual Shi’ite families who suffered loss of husbands, brothers, wives and children, homes and livelihoods? Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, when asked about the deaths of half a million Iraqi children deprived of medicine under the US sanctions on Saddam, said it was “a hard choice… but it was worth it.” That is the comforting Olympian strategic view, uncomplicated by ground realities for real human beings.

What strategic gains can we tote up for the US alongside Iraqi losses? For the US, virtually nothing gained; indeed, it’s been a serious net loss in geopolitical terms. Few Iraqis are grateful. An Iraq that has always displayed strong Arab nationalist tendencies will not likely now change its colors or learn to love Israel.

Iran is now recognized as the real winner of the Iraq war. The Iraqi internal struggle has spread across into Syria, presenting the US with choices nearly all of which are highly unpalatable. Saudi Arabia has now felt the need to unleash a vicious sectarian conflict that destabilizes the Gulf, the Arabian Peninsula, Lebanon, Syria, even Pakistan. [Continue reading…]

The myth of American exceptionalism

Andranik Migranyan writes: When the Soviet Union collapsed, America loomed as the gleaming superpower. It looked like the country had solved all of its problems. It was the envy of the world. An end of history loomed. No longer. History has come back with a vengeance. And today, after a decade of ruinous wars, the only things worth copying are the memories.

Americans are only beginning to comprehend their difficulties. Perhaps this should not be surprising. For Americans have long been weaned on the notion that they represent an exceptional nation. And, to be fair, the American belief in exceptionalism is not exceptional. Quite the contrary. Throughout history, countries and peoples have believed that they were exceptional. The ancient Greeks believed it, and called everyone else “barbarian.” So did the Romans, who conquered the world and believed they were gods. In more recent history, we had the Anglo-Saxons, who built the British Empire, which, in its expanse, spread further and wider than any previous imperium. Russia, too, is intimately acquainted with the idea of its own exceptionalism. We need only recall Hegumen Philotheus of Pskov, who talked about Moscow being the third Rome and that there would not be a fourth one. The idea of Russian exceptionalism was even more strongly expressed in Marxist-Leninist ideology, when Moscow created a denationalized ideological empire with a calling to free mankind from the tyranny of capitalism, and believed it had a historic mission to bring happiness to the entire world through a global victory of socialism, and later communism. It claimed that all people in the world would enjoy not only equality of opportunity, but of results. As a rule, all these ideas of exceptionalism rested on the twin pillars of ideology and myths.

Myths and ideological impulses abound in American history, too. The uniqueness of the country, its isolation from the rest of the world, and the unprecedented opportunity for growth and prosperity created the myth of the U.S. as a promised land that bestows upon its people unlimited room for development, personal freedom, entrepreneurship, and wealth. The American people, as the myth goes, enjoy and possess a global leadership mandate to enlighten the rest of the world and spread democratic values and institutions. At certain stages, when countries and people seem to be experiencing progress, they believe in their own myths as it seems fate itself is leading them forward and reality appears to bolster their claims to exceptionalism and a special place in the world. In this sense, American exceptionalism as a part of the American dream has long received confirmation in the continued development of both American society and the American state.

One of the main ideas of the American dream and American exceptionalism is that of freedom of the land, in which free people arrived and settled, and by the strength of their honest labor and the Protestant Ethic, achieved great results in their work, bringing prosperity to themselves and others. At the heart of this American dream and exceptionalism, lay the foundational notion that people have unlimited possibility to move up the social ladder without regard to national origin, starting social stratum, ethnic, religious or other association by birth, because society provided unlimited opportunity for economic, socio-cultural, or other advancement.

Another, very important feature of American exceptionalism was the certainty of Americans that they had the best Constitution–one that was created by a single stroke, thanks to the genius of the Founding Fathers, regarded by many as legendary demi-gods. Then there is the belief that American society is a nearly classless one. Here is a society that effectively battled poverty and created just relations between classes and social groups.

The problem comes, however, when these idealized myths run up against bleak realities. [Continue reading…]

Imagine

Graham E. Fuller writes: Is it possible that President Obama — without articulating it, perhaps without even fully intending it — may have strayed into the radical reforging of American foreign policy?

For the first time since the fall of the Soviet Union — or even the end of World War II — a linked body of enshrined foreign policy axioms may be quietly unraveling: American exceptionalism, American unilateralism, America as world policeman, moral commentator and hector, global hegemon and architect of a “world order.” Yesterday bombs were about to fall on Syria, now they are suspended. After months — years, decades — of talk about possible air strikes on Iran, suddenly we receive accounts of civil exchanges between the American and the Iranian presidents. These may only be false starts, but the larger implications beckon and burgeon. They start with the Middle East but radiate out to touch relations with Russia, China, Israel and the U.N., for starters.

Neoconservatives, hawks and liberal interventionists are aghast; progressives are heartened but holding their breath. Witness the mirror imaging in the U.S. media around these developments. The traditional nostrums don’t vary: The U.S. must draw red lines; lines once drawn must be acted upon; U.S. credibility is at stake; military readiness must be pumped to permanent alert in the Middle East to meet permanent security threats; American monopoly of decision-making must be jealously husbanded on all that moves in the world. Hawks stand with liberal interventionists, fearful that Obama is giving away the American store in acts of colossal naiveté, weakness and inexperience. Progressives perceive in these same acts the first glimmers of wisdom and rationality creeping into U.S. policy formulation — hints of strategic perestroika that just might rescue the U.S. from spiraling decades of foreign policy disasters that have undermined the country in countless ways: wartime presidents, global recoil from our policies, massive defense budgets, self-fulfilling proclamation of enemies, interventions, national paranoia, the building of a national security state, and pervasive intrusion into citizens’ private lives in the quest to keep America safe from tireless enemies. [Continue reading…]

The dangers of American exceptionalism

Janice Kennedy writes: My fellow North Americans, can we talk? Yes, I mean you, my starred-and-striped friends.

I’ve been mesmerized by the election campaign that will send you to the polls shortly, and I’d love to bounce an idea off you.

True, I’m an outsider. And I know what you think about outsiders, when you’re even aware they exist. (We Canadians sometimes get huffy that you pay no attention to us, but we shouldn’t. Unless you’re being attacked, you don’t pay attention to anyone beyond your borders.)

But I hope, as continental cousins, you’ll give me a moment of your time.

Here’s my idea. How about climbing down the hill? How about abandoning that shining city you love so much, and joining the rest of us here in the real world?

I realize that will be hard. The “city upon a hill” has been your informing inspirational metaphor since John Winthrop, the Puritan governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, invoked it in a 1630 sermon. Be a beacon unto the world, he urged the colonists. It’s a powerful image, crucial to your nation-building mythology. I can see why you’d be loath to abandon it.

But it’s time. American exceptionalism is no longer taking you where you need to be.

As long as you keep insisting you’re the biggest and best (a superiority complex that really grates on your world neighbours, whether in the Middle East or next door), your arrogant fantasy deprives you of the realities you need to fix your problems. In truth, you’re far from the best in many areas, as a brilliant essay in last Sunday’s New York Times suggested.

In The Opiate of Exceptionalism, reporter Scott Shane pointed to such things as the U.S. ranking in child poverty (34th of 35 countries); higher education among young adults (14th); infant mortality (worse than 48 other countries); incarceration rates, guns and obesity (top spot in all three).

And your cradle of modern democracy has become a sick joke, whether your gauge is woeful voter turnout (the U.S. ranks a distant last among G8 nations) or the plutocratic politics you have created.

But there has been no suggestion of such truths, from either party, during the campaign. In the presidential debates, there wasn’t even a hint that the U.S. is anything less than naturally the brightest and best. The mainstream credo of American exceptionalism means that some truths simply cannot be acknowledged.

In Tuesday’s debate (ostensibly about foreign policy, though the “foreign” seemed marginal), the president asked Mitt Romney how America can be expected to lead the world if it doesn’t maintain the world’s best school system — the assumption being that it’s already in place. Except it’s not.

Exceptionalism not only doesn’t recognize the truth, it doesn’t even accept that it might exist.

Nor does it accept abiding by the same rules that govern everyone else. Consider the murder of Osama bin Laden by Navy Seals — or other enemies, by drones — approved by a liberal president and applauded enthusiastically by Americans of all political stripes.

Romney (a classic exceptionalist, and not just because his Mormonism holds that the Garden of Eden was in Missouri) even voiced support for Obama’s kill missions during Monday’s debate. It is indeed desirable, he suggested from an ethical landscape shaped in the Wild West, to shoot up the bad guys.

In your city on the hill, might is usually right.

The thing is, you do yourselves no favours, at home or abroad, with your misplaced swaggering. We all like to think we live in “the greatest country in the world,” but only you Americans believe it wholeheartedly. Your claim to greatness is legitimate, but THE greatest? Ever? [Continue reading…]

The ‘only in America’ myth

Nima Shirazi writes: “Only in America” is a refrain heard time and again in this country’s political discourse. According to both Democrats and Republicans, the United States is a singular nation: one in which anyone can achieve anything if you have a dream and the will to work hard; a place wherein upward mobility is assumed and someone born into crushing poverty and brutal socioeconomic conditions can reach the highest levels of wealth, success and power by sheer grit and determination.

Obviously the reality in this exceptional nation of ours is quite different.

Nevertheless, an MSNBC montage perfectly illustrates the ubiquity of this mythologized narrative of American up-by-your-bootstrapism at this past week’s Republican National Convention. Watch here:

Vice Presidential candidate Paul Ryan, who is worth millions due to investments and inheritance from his wife’s trust fund, spoke of menial labor as a stepping stone for greatness:

When I was waiting tables, washing dishes, or mowing lawns for money, I never thought of myself as stuck in some station in life. I was on my own path, my own journey, an American journey where I could think for myself, decide for myself, define happiness for myself. That’s what we do in this country. That’s the American Dream.

Only in America. [Continue reading…]

America in an era of enemy deprivation syndrome

In a speech in Washington DC yesterday, Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr. (USFS, Ret.), said: The United States remains the world’s only superpower but the diffusion of wealth and power to regions beyond the North Atlantic has greatly reduced our military’s ability to shape trends and events around the world. China, in particular, is emerging as an immovable military object, if not yet an irresistible military force. Our political influence, economic clout, and self-confidence are not what they used to be. The “sequester” and the political dysfunction that led us to it promise to weaken us still more. Major adjustments in U.S. policies and diplomacy are overdue.

Global governance was once mainly a vector of the struggle between the two superpowers and the blocs they led. After Moscow defaulted on the Cold War and dropped out of the contest for worldwide dominance, Americans briefly imagined that our matchless economic strength and unchallengeable military supremacy would enable us unilaterally to shape the world to our advantage. In the first decade of this century, however, the wizards of Wall Street brought down the global economy even as they discredited the so-called “Washington consensus” and emasculated the once-robust image of American capitalism.

Meanwhile, much of the world was disappointed by the lack of U.S. leadership on other issues ranging from climate change to peace in the Middle East. People everywhere looked hopefully to worldwide institutions, like the United Nations, the G-20, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization. None of them proved up to the job. Responsibility for the regulation of the planetary political economy began to devolve to its regions, if only by default.

The globally coherent worldwide order that American power configured itself to enforce after the Cold War is clearly morphing into something new. We can see the outlines of the new order even if we cannot yet make out its details and don’t know what to call it. The “post-Cold War era” is long past. The “American Century” ended eleven years ago, on 9/11. We are exiting the “age of antiterrorism.” We are uncertain against whom we should deploy our incomparable military might or to what international purposes we should bend ourselves.

Call it what you will. This is an era of enemy deprivation syndrome. There is no overarching contest to define our worldview. The international system is once again governed by multiple contentions and shifting strategic geometries. In such a world, diplomatic agility is as important as constancy of commitment – or more so.

Before the Cold War, the United States twice fought in coalition with Britain, France, Australia, Canada, and a few other countries, but we had no permanent alliances. The Soviet threat and the need to deal with the instabilities that attended the end of European empires in Asia and Africa led Americans to reverse our traditional aversion to foreign entanglements and to embrace them with a vengeance. The United States ultimately extended formal protection to about a fourth of the world’s countries and informal protection to nearly another fourth. In our usage, the word “ally” lost its original sense of “accomplice” and came to mean “protectorate,” not partner.

There have been huge changes in the global security environment since the collapse of our Soviet enemy. But, there have been no adjustments at all in our alliance and defense commitments to foreign nations – other than their enlargement. The alliance structure we built in the Cold War has long outlived the foe it was created to counter. Remarkably, however, the preservation of our prestige at the head of that alliance structure seems to have become the principal objective of our foreign policy. Carrying on with approaches that address long-disappeared realities rather than adjusting to new circumstances is patently dysfunctional behavior. It represents the triumph of complacency and inertia over reason, statesmanship, and strategy. [Continue reading…]

Guns, violence, and American identity

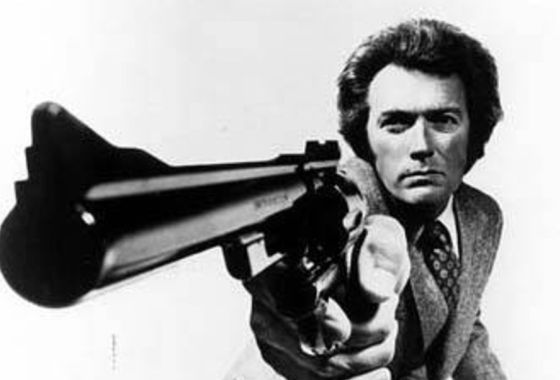

Michael Vlahos writes: Though painful, this statement cannot be avoided: The gun-massacre of innocents is integral to the American way of life. Call it part of our foundational myth. It is the red reality through which a continent was taken and settled.

Today, we call an act like the mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado, or the even more recent one in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, “senseless.” Yet, we should face these events as what they really are, a much bigger national tradition. Ritual slaying is everywhere in our American history, especially sacrificial killing with guns.

Even if we cannot admit this, American exceptionalism is never better illustrated than in ritual human execution. Other cultures have slaughterers. Only we have made ritual killers such a mirror of us. In our history and our cinema, there are a few — like John Brown — we even celebrate.

Our gun-slinging killing rituals are also dark expressions of a political ethos that surrounds the theology of the citizen’s relationship to the state. “Citizen and state” is the most contentious creedal element in national identity, and is itself argued through the symbolic venue of killing with a gun. Pro-gun and anti-gun sectarianism remains the deepest fissure, a split almost, in our national identity today.

Fast food and strip mall, school and university shootings around the country should raise an existential national question: Why are gun-massacres so rooted in the American way of life — and so tied to the political struggle over collective identity?

In recent weeks, so many of us argued these bitter contentions, without ever being able to engage the core question. The anti-gun sect rails against “the gun culture,” while pro-gun acolytes hold high the banner of liberty and virtue put at risk by the evil deranged.

Neither of these partisan visions — almost religious in their incanted rhetoric — want to admit that America’s cultural mix of gun and justice, liberty and order, has embedded within all of us a collective national vision of righteous violence — which is all too often revealed to us in the dark mirror of deranged killing. It is not a gun culture, but rather an ethos in which the gun is both instrument and symbol: That we all share. [Continue reading…]

Why children will become crippled, thanks to the CIA

Glenn Greenwald writes: Americans of all types — Democrats and Republicans, even some Good Progressives — are just livid that a Pakistani tribal court (reportedly in consultation with Pakistani officials) has imposed a 33-year prison sentence on Shakil Afridi, the Pakistani physician who secretly worked with the CIA to find Osama bin Laden on Pakistani soil. Their fury tracks the standard American media narrative: by punishing Dr. Afridi for the “crime” of helping the U.S. find bin Laden, Pakistan has revealed that it sympathizes with Al Qaeda and is hostile to the U.S. (NPR headline: “33 Years In Prison For Pakistani Doctor Who Aided Hunt For Bin Laden”; NYT headline: “Prison Term for Helping C.I.A. Find Bin Laden”). Except that’s a woefully incomplete narrative: incomplete to the point of being quite misleading.

What Dr. Afridi actually did was concoct a pretextual vaccination program, whereby Pakistani children would be injected with a single Hepatitis B vaccine, with the hope of gaining access to the Abbottabad house where the CIA believed bin Laden was located. The plan was that, under the ruse of vaccinating the children in that province, he would obtain DNA samples that could confirm the presence in the suspected house of the bin Laden family. But the vaccine program he was administering was fake: as Wired‘s public health reporter Maryn McKenna detailed, “since only one of three doses was delivered, the vaccination was effectively useless.” An on-the-ground Guardian investigation documented that ”while the vaccine doses themselves were genuine, the medical professionals involved were not following procedures. In an area called Nawa Sher, they did not return a month after the first dose to provide the required second batch. Instead, according to local officials and residents, the team moved on.”

That means that numerous Pakistani children who thought they were being vaccinated against Hepatitis B were in fact left exposed to the virus. Worse, international health workers have long faced serious problems in many parts of the world — including remote Muslim areas — in convincing people that the vaccines they want to give to their children are genuine rather than Western plots to harm them. These suspicions have prevented the eradication of polio and the containment of other preventable diseases in many areas, including in parts of Pakistan. This faux CIA vaccination program will, for obvious and entirely foreseeable reasons, significantly exacerbate that problem.

As McKenna wrote this week, this fake CIA vaccination program was “a cynical attempt to hijack the credibility that public health workers have built up over decades with local populations” and thus “endangered the status of the fraught polio-eradication campaign, which over the past decade has been challenged in majority-Muslim areas in Africa and South Asia over beliefs that polio vaccination is actually a covert campaign to harm Muslim children.” She further notes that while this suspicion “seems fantastic” to oh-so-sophisticated Western ears — what kind of primitive people would harbor suspicions about Western vaccine programs? – there are actually “perfectly good reasons to distrust vaccination campaigns” from the West (in 1996, for instance, 11 children died in Nigeria when Pfizer, ostensibly to combat a meningitis outbreak, conducted drug trials — experiments — on Nigerian children that did not comport with binding safety standards in the U.S.).

When this fake CIA vaccination program was revealed last year, Doctors Without Borders harshly denounced the CIA and Dr. Afridi for their “grave manipulation of the medical act” that will cause “vulnerable communities – anywhere – needing access to essential health services [to] understandably question the true motivation of medical workers and humanitarian aid.” The group’s President pointed out the obvious: “The potential consequence is that even basic healthcare, including vaccination, does not reach those who need it most.” That is now clearly happening, as the CIA program “is casting its shadow over campaigns to vaccinate Pakistanis against polio.” Gulrez Khan, a Peshawar-based anti-polio worker, recently said that tribesman in the area now consider public health workers to be CIA agents and are more reluctant than ever to accept vaccines and other treatments for their children. [Continue reading…]

In March, OnIslam.net reported: The killing of Osama bin Laden in a US raid following a fake vaccination campaign to track Al-Qaeda leader is casting its shadow over campaigns to vaccinate Pakistanis against polio.

“They (tribesmen) consider us CIA agents, who under the guise of anti-polio campaign, are there to look for other Al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders,” Gulrez Khan, a Peshawar-based anti-polio worker, told OnIslam.net.

The government and NGOs have launched campaigns to vaccinate residents of north-western Pakistan against polio.

But the campaigns have been resisted by residents, who are worried that the campaigns are only meant to hunt down Taliban tribesmen.

“It’s been over ten months since the Al-Qaeda Chief Osama Bin Laden is dead, but his ghost is still haunting our efforts not only to persuade the people in the country’s northwestern parts, particularly in the tribal belt, to get their kids vaccinated, but also to move freely,” Khan said.

A pundit’s rosy view of the Pax Americana

Andrew Bacevich reviews Robert Kagan’s The World America Made: Call it a hallowed tradition. To invest their views with greater authority, big thinkers—especially those given to pontificating about the course of world history—appropriate bits of wisdom penned by brand-name sages. Nothing adds ballast to an otherwise frothy argument like a pithy quotation from John Quincy Adams or George F. Kennan or Reinhold Niebuhr. In The World America Made, a slim volume of mythopoeia decked out in analytic drag, the historian and pundit Robert Kagan cites all three of those renowned figures. For real inspiration, however, he turns to a different and altogether unlikely source: Hollywood director Frank Capra. The World America Made begins and ends with Kagan urging Americans to heed the lessons of that hoariest of Christmas fantasies, It’s a Wonderful Life.

Remember Clarence, the probationary guardian angel? Clarence saves George Bailey from suicidal despair (and earns his wings) by showing George what a miserable place Bedford Falls would have been without him.

As Kagan sees it, America’s impact on history mirrors George Bailey’s impact on Bedford Falls. Thanks to the power wielded by the United States, the entire postwar era has been “a golden age for humanity.” Among the hallmarks of this golden age have been the spread of democracy, a huge reduction in world poverty, and, above all, “the absence of war among great powers.” All of this Kagan ascribes to the United States and to what he calls the “American world order.”

Accept any diminution of American preeminence and you can kiss the golden age goodbye. Just like Bedford Falls without George Bailey, the world will inevitably become a dark and miserable place. Upstart nations will “demand particular spheres of influence,” and the weakened United States will “have little choice but to retrench and cede some influence.” China, Russia, India, and others will begin flexing their expansionist muscles, with doom and gloom sure to follow. “The notion that the world could make a smooth and entirely peaceful transition” to a new order, Kagan writes, is mere “wishful thinking.”

Fortunately, none of this need come to pass if only Americans will be of good heart and heed the counsel of their own guardian angel, whose name happens to be Robert Kagan. His self-assigned mission is to prevent the United States from “committing preemptive superpower suicide out of a misplaced fear of declining power.” After all, our decline is far from inevitable. The key is to believe. Once George Bailey recovers his faith, “he solves his [firm’s] fiscal crisis and lives happily ever after.” If Americans just keep the faith, they can do likewise. [Continue reading…]

The American Century is over — good riddance

Andrew Bacevich writes: As someone who teaches both history and international relations, I have one foot in each camp. I’m interested in what has already happened. And I’m interested in what will happen next. In my teaching and my writing, I try to locate connecting tissue that links past to present. Among the devices I’ve employed to do that is the concept of an “American Century.”

That evocative phrase entered the American lexicon back in February 1941, the title of an essay appearing in Life magazine under the byline of the publishing mogul Henry Luce. In advancing the case for U.S. entry into World War II, the essay made quite a splash, as Luce intended. Yet the rush of events soon transformed “American Century” into much more than a bit of journalistic ephemera. It became a summons, an aspiration, a claim, a calling, and ultimately the shorthand identifier attached to an entire era. By the time World War II ended in 1945, the United States had indeed ascended — as Luce had forecast and perhaps as fate had intended all along—to a position of global primacy. Here was the American Century made manifest.

I love Luce’s essay. I love its preposterous grandiosity. I delight in Luce’s utter certainty that what we have is what they want, need, and, by gum, are going to get. “What can we say and foresee about an American Century?” he asks. “It must be a sharing with all peoples of our Bill of Rights, our Declaration of Independence, our Constitution, our magnificent industrial products, our technical skills.” I love, too, the way Luce guilelessly conjoins politics and religion, the son of Protestant missionaries depicting the United States as the Redeemer Nation. “We must undertake now to be the Good Samaritan of the entire world.” How to do that? To Luce it was quite simple. He pronounced it America’s duty “as the most powerful and vital nation in the world … to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.” Would God or Providence have it any other way?

Luce’s essay manages to be utterly ludicrous and yet deeply moving. Above all, this canonical assertion of singularity — identifying God’s new Chosen People — is profoundly American. (Of course, I love Life in general. Everyone has a vice. Mine is collecting old copies of Luce’s most imaginative and influential creation—and, yes, my collection includes the issue of February 17, 1941.)

Alas, the bracing future that Luce confidently foresaw back in 1941 has in our own day slipped into the past. If an American Century ever did exist, it’s now ended. History is moving on—although thus far most Americans appear loath to concede that fact. [Continue reading…]

America is rotting from the inside

Michael A. Cohen points out that focusing on the issue of U.S. power vis-à-vis other countries has the effect of directing attention away from this country’s domestic failings.

[B]y virtually any measure, a closer look at the state of the United States today tells a sobering tale of rapid and unchecked decay and deterioration in a host of areas. While not all of them are generally considered elements of national security, perhaps they should be.

Let’s start with education, which almost any observer would agree is a key factor in national competitiveness. The data is not good. According to the most recent OECD report on global education standards, the United States is an average country in how it educates its children — 12th in reading skills, 17th in science, and 26th in math. The World Economic Forum ranks the United States 48th in the quality of its mathematics and science education, even though we spend more money per student than almost any country in the world.

America’s high school graduation rate is lower today that it was in the late 1960s and “kids are now less likely to graduate from high school than their parents,” according to an analysis released last year by the Editorial Projects in Education Research Center. In fact, not only is the graduation rate worse than many Western countries, the United States is now the only developed country where a higher percentage of 55 to 64-year-olds have a high school diploma than 25 to 34-year-olds.

While the United States still maintains the world’s finest university system, college graduation rates are slipping. Among 25 to 34-year-olds, America trails Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Ireland, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom in its percentage of college graduates. This speaks, in some measure, to the disparities that are endemic in the U.S. education system. If you are poor in America, chances are you attend a school that underperforms, are taught by teachers that are not as effective, and have test scores that lag far behind your more affluent counterparts (the same is true if you are black or Hispanic — you lag behind your white counterparts). Can a country be a great global power if its education system is fundamentally unequal and is getting steadily worse?

Video: Ralph Nader and Bruce Fein — America’s lawless empire: The constitutional crimes of Bush and Obama

The decline of the American empire

American and Israeli exceptionalism

Foreign Policy‘s latest issue looks at American exceptionalism and Stephen Walt writes:

Over the last two centuries, prominent Americans have described the United States as an “empire of liberty,” a “shining city on a hill,” the “last best hope of Earth,” the “leader of the free world,” and the “indispensable nation.” These enduring tropes explain why all presidential candidates feel compelled to offer ritualistic paeans to America’s greatness and why President Barack Obama landed in hot water — most recently, from Mitt Romney — for saying that while he believed in “American exceptionalism,” it was no different from “British exceptionalism,” “Greek exceptionalism,” or any other country’s brand of patriotic chest-thumping.

Most statements of “American exceptionalism” presume that America’s values, political system, and history are unique and worthy of universal admiration. They also imply that the United States is both destined and entitled to play a distinct and positive role on the world stage.

The only thing wrong with this self-congratulatory portrait of America’s global role is that it is mostly a myth. Although the United States possesses certain unique qualities — from high levels of religiosity to a political culture that privileges individual freedom — the conduct of U.S. foreign policy has been determined primarily by its relative power and by the inherently competitive nature of international politics. By focusing on their supposedly exceptional qualities, Americans blind themselves to the ways that they are a lot like everyone else.

No doubt it behooves Americans to recognize the things that tie this country to the rest of the world, but there is an aspect of exceptionalism Walt does not touch upon — one that sets apart American and Israeli exceptionalism from most others: the exceptionalism of colonizers.

Nations that come into existence by dispossessing, imprisoning and slaughtering the indigenous population have two problems with history:

1. Its ugliness makes it hard to glorify.

2. Its shortness exposes the tenuousness of any claim that this is “our land”.

Others look back at their national history and can trace a rich tapestry of events, places, and people in which the contours of their nation have over the preceding centuries been carved by culture and inscribed in geography. All around are stepping stones that lead into the near, middling, distant, and sometimes ancient past. The punctuations of history rest on a continuum.

If without sentiment we look back into our ancestry as Americans or Israelis, we see migrants and murderers fast preceded by a void. Our actual roots in abandoned lands take us far away from the very thing that supposedly makes us exceptional.

With histories much harder to glorify, we find the need to make our pasts less linear and more mythically grandiose. We ignore the catastrophes that we imposed on others. We didn’t steal the land; it was a gift from God.