Scott Shane writes: the Zhuhai air show in southeastern China last November, Chinese companies startled some Americans by unveiling 25 different models of remotely controlled aircraft and showing video animation of a missile-armed drone taking out an armored vehicle and attacking a United States aircraft carrier.

The presentation appeared to be more marketing hype than military threat; the event is China’s biggest aviation market, drawing both Chinese and foreign military buyers. But it was stark evidence that the United States’ near monopoly on armed drones was coming to an end, with far-reaching consequences for American security, international law and the future of warfare.

Eventually, the United States will face a military adversary or terrorist group armed with drones, military analysts say. But what the short-run hazard experts foresee is not an attack on the United States, which faces no enemies with significant combat drone capabilities, but the political and legal challenges posed when another country follows the American example. The Bush administration, and even more aggressively the Obama administration, embraced an extraordinary principle: that the United States can send this robotic weapon over borders to kill perceived enemies, even American citizens, who are viewed as a threat.

“Is this the world we want to live in?” asks Micah Zenko, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “Because we’re creating it.”

What was a science-fiction scenario not much more than a decade ago has become today’s news. In Iraq and Afghanistan, military drones have become a routine part of the arsenal. In Pakistan, according to American officials, strikes from Predators and Reapers operated by the C.I.A. have killed more than 2,000 militants; the number of civilian casualties is hotly debated. In Yemen last month, an American citizen was, for the first time, the intended target of a drone strike, as Anwar al-Awlaki, the Qaeda propagandist and plotter, was killed along with a second American, Samir Khan.

If China, for instance, sends killer drones into Kazakhstan to hunt minority Uighur Muslims it accuses of plotting terrorism, what will the United States say? What if India uses remotely controlled craft to hit terrorism suspects in Kashmir, or Russia sends drones after militants in the Caucasus? American officials who protest will likely find their own example thrown back at them.

Category Archives: U.S. exceptionalism

After September 11: our state of exception

Mark Danner writes:

We are living in the State of Exception. We don’t know when it will end, as we don’t know when the War on Terror will end. But we all know when it began. We can no longer quite “remember” that moment, for the images have long since been refitted into a present-day fable of innocence and apocalypse: the perfect blue of that late summer sky stained by acrid black smoke. The jetliner appearing, tilting, then disappearing into the skin of the second tower, to emerge on the other side as a great eruption of red and yellow flame. The showers of debris, the falling bodies, and then that great blossoming flower of white dust, roiling and churning upward, enveloping and consuming the mighty skyscraper as it collapses into the whirlwind.

To Americans, those terrible moments stand as a brightly lit portal through which we were all compelled to step, together, into a different world. Since that day ten years ago we have lived in a subtly different country, and though we have grown accustomed to these changes and think little of them now, certain words still appear often enough in the news—Guantánamo, indefinite detention, torture—to remind us that ours remains a strange America. The contours of this strangeness are not unknown in our history—the country has lived through broadly similar periods, at least half a dozen or so, depending on how you count; but we have no proper name for them. State of siege? Martial law? State of emergency? None of these expressions, familiar as they may be to other peoples, falls naturally from American lips.

What are we to call this subtly altered America? Clinton Rossiter, the great American scholar of “crisis government,” writing in the shadow of World War II, called such times “constitutional dictatorship.” Others, more recently, have spoken of a “9/11 Constitution” or an “Emergency Constitution.” Vivid terms all; and yet perhaps too narrowly drawn, placing as they do the definitional weight entirely on law when this state of ours seems to have as much, or more, to do with politics—with how we live now and who we are as a polity. This is in part why I prefer “the state of exception,” an umbrella term that gathers beneath it those emergency categories while emphasizing that this state has as its defining characteristic that it transcends the borders of the strictly legal—that it occupies, in the words of the philosopher Giorgio Agamben, “a position at the limit between politics and law…an ambiguous, uncertain, borderline fringe, at the intersection of the legal and the political.”

Call it, then, the state of exception: these years during which, in the name of security, some of our accustomed rights and freedoms are circumscribed or set aside, the years during which we live in a different time. This different time of ours has now extended ten years—the longest by far in American history—with little sense of an ending. Indeed, the very endlessness of this state of exception—a quality emphasized even as it was imposed—and the broad acceptance of that endlessness, the state of exception’s increasing normalization, are among its distinguishing marks.

News roundup — May 9

Bin Laden’s death doesn’t end his fear-mongering value

Glenn Greenwald writes: On Friday, government officials anonymously claimed that “a rushed examination” of the “trove” of documents and computer files taken from the bin Laden home prove — contrary to the widely held view that he “had been relegated to an inspirational figure with little role in current and future Qaeda operations” — that in fact “the chief of Al Qaeda played a direct role for years in plotting terror attacks.” Specifically, the Government possesses “a handwritten notebook from February 2010 that discusses tampering with tracks to derail a train on a bridge,” and that led “the Obama administration officials on Thursday to issue a warning that Al Qaeda last year had considered attacks on American railroads.” That, in turn, led to headlines around the country like this one, from The Chicago Sun-Times:

The reality, as The New York Times noted deep in its article, was that “the information was both dated and vague,” and the official called it merely “aspirational,” acknowledging that “there was no evidence the discussion of rail attacks had moved beyond the conceptual stage“ In other words, these documents contain little more than a vague expression on the part of Al Qaeda to target railroads in major American cities (“focused on striking Washington, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago,” said the Sun-Times): hardly a surprise and — despite the scary headlines — hardly constituting any sort of substantial, tangible threat.

But no matter. Even in death, bin Laden continues to serve the valuable role of justifying always-increasing curtailments of liberty and expansions of government power. (Salon)

Bin Laden killing in legal gray zone

David Axe writes: The early-morning raid that killed Osama bin Laden was, according to CIA Director Leon Panetta, “the culmination of intense and tireless efforts on the part of many dedicated agency officers.” Panetta also thanked the “strike team, whose great skill and courage brought our nation this historic triumph.”

But it’s unclear who was on the strike team — the 25 people aboard two specially modified Army helicopters. Most of the “trigger-pullers” were, apparently, Navy commandos from the famed SEAL Team Six.

At the “pointy end” — a Beltway euphemism for combat — the operation targeting bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan, looked overwhelmingly military. But the months-long process of gathering intelligence and planning had a CIA flavor.

Indeed, President Barack Obama described it as agency-led. The intelligence community pinpointed bin Laden’s location. Panetta monitored the raid in real time from Langley. The assault team may have included CIA operatives. Senior administration officials called it a “team effort.”

But did the CIA have people on the ground in Abbottabad? It’s not an academic question. Exactly who was on the strike force that killed bin Laden has major policy implications.

CIA presence places the operation on one side of an increasingly fuzzy legal boundary between two distinct U.S. legal codes: one exclusive to the military and another that defines the terms of open warfare for the whole U.S. government.

The extent of the CIA’s involvement also has serious implications with regard to a chain of presidential executive orders that prohibit Americans from participating in the assassination of foreign leaders. (Politico)

US spy in Pakistan outed as White House demands intelligence from bin Laden raid

White House has demanded that Pakistan hand over intelligence seized from Osama bin Laden’s compound as relations between the two allies hit a new crisis over the outing of America’s top spy in Islamabad.

Mark Carlton, the purported CIA station chief, was named by a Pakistani newspaper and a private television news network over the weekend, the second holder of that post in less than a year to have his cover blown by the media, presumed to have official consent.

The reports documented a meeting between Mr Carlton and the head of Pakistan’s spy agency, the Inter- Services Intelligence, suggesting that the information came from them.

Washington has refused to comment on the development, which comes amid worsening relations between the US and Pakistan over how bin Laden came to be sheltering in a fortified compound in a garrison town.

Anger is mounting in Pakistan over how the US was able to carry out the raid in Abbottabad without detection, with calls for the Government to resign. (The Times)

Leak of CIA officer’s name is sign of rift with Pakistan

The prime minister’s statements, along with the publication of the name of the C.I.A. station chief, signaled the depths of the recriminations and potential for retaliation on both sides as American officials demand greater transparency and cooperation from Pakistan, which has not been forthcoming.

The Pakistani spy agency, Inter Services Intelligence Directorate, gave the name of the station chief to The Nation, a conservative daily newspaper, American and Pakistani officials said.

The name appeared spelled incorrectly but in a close approximation to a phonetic spelling in Saturday’s editions of The Nation, a paper with a small circulation that is supportive of the ISI. The ISI commonly plants stories in the Pakistani media and is known to keep some journalists on its payroll.

Last December, American officials said the cover of the station chief at the time was deliberately revealed by the ISI. As a result, he was forced to leave the country. (New York Times)

U.S. raises pressure on Pakistan in raid’s wake

President Obama’s national security adviser demanded Sunday that Pakistan let American investigators interview Osama bin Laden’s three widows, adding new pressure in a relationship now fraught over how Bin Laden could have been hiding near Islamabad for years before he was killed by commandos last week.

Both the adviser, Thomas E. Donilon, and Mr. Obama, in separate taped interviews, were careful not to accuse the top leadership of Pakistan of knowledge of Bin Laden’s whereabouts in Abbottabad, a military town 35 miles from the country’s capital. They argued that the United States still regards Pakistan, a fragile nuclear-weapons state, as an essential partner in the American-led war on Islamic terrorism.

But in repeatedly describing the trove of data that a Navy Seal team seized after killing Bin Laden as large enough to fill a small college library, Mr. Donilon seemed to be warning the Pakistanis that the United States might soon have documentary evidence that could illuminate who, inside or outside their government, might have helped harbor Bin Laden, the leader of Al Qaeda, who had been the world’s most wanted terrorist.

The United States government is demanding to know whether, and to what extent, Pakistani government, intelligence or military officials were complicit in hiding Bin Laden. His widows could be critical to that line of inquiry because they might have information about the comings and goings of people who were aiding him. (New York Times)

* * *

The forgotten frontline in Libya’s civil war

It is the unknown frontline in Libya’s civil war, a rebel town besieged by Gaddafi’s forces but almost ignored by the outside world.

Rockets and Scud missiles pour down. Water is running short. Tens of thousands are desperately trying to flee.

But transfixed by the horrors of Misurata, the international community – and the Nato military alliance – have all but overlooked the closely parallel drama in the mountain towns of Zintan and Yafran, little more than an hour’s drive from the capital.

“We have been under fire for about an hour and a half now,” said one Zintan resident, Mustafa Haider, by telephone from the town on Friday afternoon.

“From the south, from the north, from the east, from everywhere. They fire with Grad missiles, Scud missiles, anything. They have tried to enter Zintan many times but they couldn’t.” Homes, schools, and the town’s main hospital had been hit, causing panic, he said. (Daily Telegraph)

Libya: end indiscriminate attacks in western mountain towns

Human Rights Watch says: Libyan government forces have launched what appear to be repeated indiscriminate attacks on mountain towns in western Libya, Human Rights Watch said today.

Accounts from refugees who fled the conflict say the attacks are killing and injuring civilians and damaging civilian objects, including homes, mosques, and a school. Human Rights Watch called on Libyan forces to cease their indiscriminate attacks on civilian areas.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 50 refugees from Libya’s western Nafusa mountains in Tunisia from April 26 to May 1, 2011, as well as doctors and aid workers assisting those in need. The refugees gave consistent and credible accounts of indiscriminate shelling and possible rocket attacks in residential areas of the rebel-controlled towns of Nalut, Takut, and Zintan. Human Rights Watch could not confirm the refugees’ accounts due to government restrictions on travel in western Libya but, taken together, they describe a pattern of attacks that would violate the laws of war.

* * *

Syria death toll rises as city is placed under siege

Amnesty International says: At least 48 people have been killed in Syria by the security forces in the last four days, local and international human rights activists have told Amnesty International, as the crackdown on the coastal city of Banias intensified.

More than 350 people – including 48 women and a 10-year-old child – are also said to have been arrested in the Banias area over the past three days with scores being detained at a local football pitch. Among those rounded up were at least three doctors and 11 injured people taken from a hospital.

“Killings of protesters are spiralling out of control in Syria – President Bashar al-Assad must order his security forces to stop the carnage immediately,” said Philip Luther, Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for the Middle East and North Africa.

Amnesty International has compiled the names of 28 people who were apparently shot dead by security forces on Friday and those of 12 others killed over the last three days.

The organization now has the names of 580 protesters and others killed since mid-March, when protests against the government of President Bashar al-Assad began.

‘House-to-house raids’ in Syrian cities

The Syrian government is continuing its weeks-long crackdown on anti-government demonstrations, arresting opponents and deploying troops in protest hubs.

Rami Abdul-Rahman, director of the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, said security forces were carrying out house-to-house raids targeting demonstration organisers and participants.

He said Monday’s raids were focused in the central city of Homs, the coastal city of Baniyas, some suburbs of the capital, Damascus, and villages around the southern flashpoint city of Deraa.

Live Blog Syria

Another activist said gunfire was heard in the town of Moadamiya, just west of the capital, Damascus, as troops carried out arrests. (Al Jazeera)

* * *

Money, power and law-twisting: The makings of the real Ezz empire

Ten years ago, as the main thrust of Egyptian society and the legal sphere was moving towards amending the constitution to make it more democratic and just, the collective brain of the regime’s inner circle was working in the opposite direction: twisting laws to fit the interests of the inner few — the oligarchs who had both wealth and political influence.

Steel magnate Ahmed Ezz, who is facing trial Today, Saturday, on charges of illegal profiteering and misuse of public funds, along with dozens of businessmen and officials considered to be close to the ousted regime, perfectly represents the marriage of wealth, party politics and undue power. Ezz became one of the first symbols that the Egyptian people decided to bring down after the January 25 Revolution.

On the night of 28 January, the headquarters of Ezz Steel in the Mohandeseen district was destroyed, along with other government headquarters and police stations, symbolising the downfall of the old regime.

“At the time he came to buy Alexandria National Iron and Steel Company (now Al-Ezz Al-Dekheila Steel Company) we had never heard of Ahmed Ezz,” said Ali Helmy, former chairman of the National Iron and Steel Company.

“The first time I met Ezz was in 1999 when Atef Ebeid, minister of the public enterprise sector at that time, invited managers of steel companies for a business dinner at a small factory in Sadat City producing galvanised iron,” recounted Helmy. “We were introduced to Ezz, a young engineer and owner of the factory.”

A few months later, continues Helmy, Ezz has already bought three million shares, accounting for LE456 million ($76.7 mln), of the Alexandria National Iron and Steel Company, and after a few months, he was appointed chairman of the company: first base for what would later become a great empire.

Ezz was born in 1959 to a family that was wealthy but not overly rich. After having graduated from the Faculty of Engineering at Cairo University in the mid-1980s, he worked as a percussionist in one of the most famous music bands at that time, Moudy and Hussein. At the time, Ezz had shown no interest in business until in 1995 his father, a steel trader, bought him a small plot of land in Sadat City and helped him build a steel factory.

His friendship with Gamal Hosni Mubarak, son of Egypt’s then president, helped to make his fortune, culminating in the buying of a huge amount of shares in Gamal’s 1998 Future Generation Foundation (FGF), a non-profit organisation that provided courses for young people to prepare them for entry to the workforce.

Several leading figures in Egypt‘s private sector, including Ahmed El-Maghrabi, former minister of tourism, and Rachid Mohamed Rachid, former minister of trade and industry were involved, and both now face trial.

From that point on, Ezz accompanied Gamal to all meetings and despite being a newcomer to politics, gradually became a familiar political face.

In 1999, the Alexandria National Iron and Steel Company faced a financial crisis due to dumped steel imports from Ukraine and other Eastern European countries coming into Egypt. Ezz quickly offered to buy shares in the troubled joint stock company. “For some reason, the biggest figures in the government helped Ezz finalise this deal,” said Helmy.

According to a 2007 report on Strategic Economic Trends by Al-Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies, In 1999, Ezz bought some 540,000 shares in less than a month. Ezz had seized more than three million shares of the company, accounting for 27.9 per cent of total shares.

By the late 1990s, Ezz started his acquisition move in the steel market, through a strategy of taking loans from the biggest banks to buy shares in steel companies.

In 1999, Ezz was appointed chairman of the National Iron and Steel Company, despite the fact that he hadn’t paid back the loans he had taken from Egypt’s major banks, according to the same report.

“The National Bank of Egypt and Bank of Cairo (Egypt’s largest public banks) favoured Ezz because of his relationship with Gamal Mubarak and helped him get the loans, while denying credit to viable businesspeople who lacked the right political pedigree; they had for instance refused to issue loans for the same company bought by Ezz (Alexandria National Iron and Steel Company) a few months earlier to help it get out of its devastating financial crisis,” said Helmy.

“Ezz’s strategy from that time on was to take loans from Egyptians banks, buy shares and take a greater role in the steel market, but the thing is, he never gave a loan back. He would pay older loans by getting new loans,” elaborates Helmy. (Ahram Online)

Hollow ‘reconciliation’ in Palestine

Ali Abunimah writes: By deciding to join the US-backed Palestinian Authority led by Mahmoud Abbas, Hamas risks turning its back on its role as a resistance movement, without gaining any additional leverage that could help Palestinians free themselves from Israeli occupation and colonial rule.

Indeed, knowingly or not, Hamas may be embarking down the same well-trodden path as Abbas’ Fatah faction: committing itself to joining a US-controlled “peace process”, over which Palestinians have no say – and have no prospect of emerging with their rights intact. In exchange, Hamas may hope to earn a role alongside Abbas in ruling over the fraction of the Palestinians living under permanent Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Whether Hamas realises it or not, it has effectively entered into a coalition with Israel and Abbas to manage the Occupied Territories, in which Hamas will have much responsibility, but little power. (Al Jazeera)

Ahmadinejad fights to preserve his dwindling power

Saeed Kamali Dehghan writes: No Iranian president has ever dared to challenge the supremacy of Ali Khamenei’s two-decade-long leadership as publicly as Mahmoud Ahmadinejad did recently in an extraordinary power struggle between him and the ayatollah.

The unprecedented confrontation at the top of the Iranian regime began only a month ago when Khamenei, the supreme leader, intervened in a cabinet appointment by reinstating a minister who had initially resigned “under pressure from Ahmadinejad”.

In reaction to the reinstatement of Heydar Moslehi, the intelligence minister at the centre of the row, Ahmadinejad apparently staged an 11-day walkout from the presidential palace and refused to chair cabinet meetings.

At first glance, Ahmadinejad’s feud with the ayatollah seemed like a conventional disagreement between two leaders of one country but in Iran, where Khamenei is described as “God’s representative on Earth”, Ahmadinejad’s opposition was extremely serious. (The Guardian)

9/11 is not the axis around which the world revolves

You can’t talk like a five-year old without ending up thinking like a five-year old, yet this is the mentality many Americans bring to bear when they look at the world through the prism of 9/11.

America is at war with “bad guys” and on Monday morning “we got him” — the baddest guy of all.

To the non-American ear there is something at turns amusing then disturbing about the fact that full-grown adults, including literate and less literate presidents, can, without any sense of irony, use this kind of comic-book language. Yet beneath these simplistic expressions is a sense of innocence that Americans cling to, born from the notion that this is a nation that can do no wrong; that at worst America can be misguided but its errors will ultimately never obscure its intrinsic virtue.

What 9/11 and its aftermath did was to widen the gap between the way America sees itself and the way it is seen by the world. If some of us might have hoped that this nation had grown up a bit over the last decade, there has been little evidence of that over the last few days.

On Thursday, President Obama was presented with an opportunity that had slipped through the fingers of his two predecessors: to “take out” Osama bin Laden.

At a moment when hesitation might have been seen as risking political suicide (Obama could have been destroyed by knowledge that he dithered and let America’s nemesis take flight), the president did just that: he put off making a decision.

Why? We’ll probably never know, but the fact was, the timing was awkward. A strike in Pakistan in the early hours of Friday would have happened at the same time that the global media’s attention was focused on London. A royal wedding and two billion viewers’ eyes represented an advertising cash-cow that few news producers would be willing to drag themselves away from.

The wedding played out and payed off just as everyone had hoped and within hours was to be followed by a drama hot enough to be turned into a Hollywood blockbuster.

US special forces swept into Pakistan and during an intense firefight ended the life and career of the most wanted terrorist on the planet. Faced by the overwhelming power of US Navy Seals, bin Laden acted just the way we’d been led to expect an evil low-life would: he used his wife as a human shield and tried to save his own skin. But justice was served — at least justice as a form of storytelling.

Only after bin Laden’s bloody body had been dumped in the Indian ocean did a more accurate and less glorious narrative emerge. This is the story that Hollywood will have a hard time telling.

The firefight was over before soldiers had even entered bin Laden’s house — a house on the edge of town, not a luxury mansion on an imposing hilltop.

Administration officials said that the only shots fired by those in the compound came at the beginning of the operation, when Bin Laden’s trusted courier, Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, opened fire from behind the door of the guesthouse adjacent to the house where Bin Laden was hiding.

After the Seal members shot and killed Mr. Kuwaiti and a woman in the guesthouse, the Americans were never fired upon again.

They simply located, shot and killed the remaining men in the house. The surviving women and nine children had their hands bound and were then left in the company of the dead — with the exception of bin Laden and his son whose bodies were removed.

Bin Laden’s 12-year-old daughter Safia is said to have witnessed her father’s death. Will Americans ever hear her story? Are the expressions on her face or those of any of the other children still etched in the memories of the soldiers who killed their parents? If so, will those memories ever be recounted or must they be consigned to a national security vault of silence?

The story of 9/11 that America has been telling itself for ten years is what drove young people to the streets to celebrate bin Laden’s death in the early hours of Monday morning, but it’s not a story that resonates much beyond these shores. It is and never was an axis around which the world was meant to revolve.

In a letter to one of Pakistan’s leading newspapers, Moez Mobeen from Islamabad, explains why the 9/11 narrative has such little meaning in a region which for most Americans is defined by the 2001 attacks.

It has long been argued by western thinkers and strategists especially the policymakers that the West is not at war with the Muslim world; that it does not believe in the clash of civilisations and that the Muslim World generally does not have any reservations about the foreign policies pursued by the western nations. This was the point which Obama emphasised in his speech announcing the death of Osama bin Laden. Whatever the American narrative be, it is certain that the Muslim world does not believe in it. It is all but obvious that Osama bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda, Mullah Omer’s Taliban, Tahir Yuldashev’s Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Ahmad Yasin’s Hamas, Abu Sayyaf’s Harkat ul Islamiyah, to name a few, are reactionary movements formed to protest and fight against foreign policies pursued by the West with regard to the Muslim world. Obama may try to present these movements as the common enemies of humanity but the fact remains that for the Muslim world these movements are resistance movements fighting the imperial forces and their allies. If indeed it is the slaughter of Muslims which worries Obama then how does he justify the death of over one million Muslims in Iraq after the US imposed a brutal and destructive war there? How does he account for the deaths of tens of thousands of innocent civilians in Afghanistan at the hands of the US forces?

The Muslim world does not view its relationship with the West through the prism of the 9/11; it does not think that the wars in Afghanistan or Iraq are legitimate. It sees its relationship with the West with regards to the foreign policies of the western countries. Justice may have been done and closure achieved for the families who suffered losses on 9/11, but the Muslim world stills mourns the death of millions of its sons and daughters with no justice and no closure in sight.

The American story is a story of power and virtue we keep telling ourselves as though it would quickly be forgotten or disbelieved if not reinforced through constant repetition. Yet what might be conceived as a form of self- and national affirmation serves no good if it refuses to accommodate reality. If our self-image is not informed and modified by the perceptions of others, it is no more than a conceit — a picture we can only believe in by refusing to see ourselves through the eyes of others.

The gun — preeminent symbol of the impotence of the American citizen

A paradox embedded in many popular symbols of power is that their greatest appeal is often found among those who perceive themselves as the most weak. Nowhere is this marriage of power and weakness more evident than in the American fetish of the handgun.

Jared Lee Loughner is apparently none too enamored with the US Constitution (though chooses right now to seek its protection), but if in the coming weeks he reveals more about the inner workings of his mind, it should come as no surprise if it turns out that he targeted Representative Gabrielle Giffords not solely because of what she represented politically but also in part because she was a woman. For an alienated young man in America, it is all too easy for sexual frustration to seek violent release through the culturally-validated possession and use of a gun.

Predictably there will now be renewed calls for stronger forms of federal gun control, though if she recovers, whether Giffords will modify her own position on gun control seems doubtful. She believes gun ownership is a constitutional right and an “Arizona tradition” and like her assailant, owns a Glock handgun.

The rational arguments in favor of tight restrictions on gun ownership are so numerous and so easy to grasp, the one thing their lack of traction makes clear is that thanks to the efforts of the gun lobby, “gun rights” has been turned into such an emotive issue that it has effectively been sequestered from rational debate.

Were any other major country to suddenly declare that it was going to adopt the American way and provide its citizens with ready access to weapons and ammunition, most observers — including most Americans — would surely recognize this as an act of national lunacy.

Gun rights in America rest solely on the claim that they represent a dimension of America’s national heritage and the character of its people. In other words, the right to bear arms can be reduced to a reason impervious to reason: because we are Americans — the Second Amendment is just a fig leaf.

But in spite of this rational dead end, I still can’t help wonder whether some leverage might be derived from linking the issue to other aspects of the American way of life which are regulated by law with little protest.

There is as far as I’m aware no movement defending the right of Americans to drive their automobiles without a licence or insurance — even though nothing underpins the American way of life more clearly than the right to drive.

If this American right can nevertheless by girded by legal restrictions, why should there not be limitations at least as equally rigorous on the ownership of guns?

If the use of a car is potentially so dangerous that it cannot be allowed without insurance, why shouldn’t someone who wants to own a lethal weapon also be required to have insurance? If legislators can’t agree on the risks involved in gun ownership, I doubt that insurance actuaries would suffer the same problem.

And if someone driving a car is required to carry a photo ID showing that they are licensed to drive, why shouldn’t every American who owns a gun?

When Arizona last summer made it legal to carry a concealed weapon without a permit, one of the cockeyed arguments among the proponents of the law was that armed Arizonans would be able to defend themselves when under attack.

It turned out yesterday in Tuscon that only one man had taken full advantage of the new law: Jared Loughner.

‘Disappeared’ Pakistanis — innocent and guilty alike — have fallen into a legal black hole

Without a single reference to President Obama’s drone war in Pakistan, extrajudicial detention of prisoners at Guantanamo, the torture of suspected terrorists, CIA-run secret prisons, rendition, presidential authorization to assassinate US citizens, or the United States’ long history of supporting governments that use their power to suppress political dissent by making their opponents “disappear,” the New York Times reports:

The Obama administration is expressing alarm over reports that thousands of political separatists and captured Taliban insurgents have disappeared into the hands of Pakistan’s police and security forces, and that some may have been tortured or killed.

The issue came up in a State Department report to Congress last month that urged Pakistan to address this and other human rights abuses. It threatens to become the latest source of friction in the often tense relationship between the wartime allies.

The concern is over a steady stream of accounts from human rights groups that Pakistan’s security services have rounded up thousands of people over the past decade, mainly in Baluchistan, a vast and restive province far from the fight with the Taliban, and are holding them incommunicado without charges. Some American officials think that the Pakistanis have used the pretext of war to imprison members of the Baluch nationalist opposition that has fought for generations to separate from Pakistan. Some of the so-called disappeared are guerrillas; others are civilians.

“Hundreds of cases are pending in the courts and remain unresolved,” said the Congressionally mandated report that the State Department sent to Capitol Hill on Nov. 23. A Congressional official provided a copy of the eight-page, unclassified document to The New York Times.

Separately, the report also described concerns that the Pakistani military had killed unarmed members of the Taliban, rather than put them on trial.

Two months ago, the United States took the unusual step of refusing to train or equip about a half-dozen Pakistani Army units that are believed to have killed unarmed prisoners and civilians during recent offensives against the Taliban. The most recent State Department report contains some of the administration’s most pointed language about accusations of such so-called extrajudicial killings. “The Pakistani government has made limited progress in advancing human rights and continues to face human rights challenges,” the State Department report concluded. “There continue to be gross violations of human rights by Pakistani security forces.”

American supremacy

Matt Miller writes:

Does anyone else think there’s something a little insecure about a country that requires its politicians to constantly declare how exceptional it is? A populace in need of this much reassurance may be the surest sign of looming national decline.

American exceptionalism is now the central theme of Sarah Palin’s speeches. The supposedly insufficient Democratic commitment to this idea will be a core Republican complaint in 2012. Conservatives assail Barack Obama for his alleged indifference to it. It’s part of their broader indictment of Obama’s fishy cosmopolitanism, his overseas “apology tours,” his didn’t-wear-the-flag-lapel-pin-until-he-had-to peevishness. Not to mention the whole anti-colonial Kenyan resentment thing the president’s got going.

Real men – real Americans – know America is the greatest country ever invented. And they shout it from the rooftops. Don’t they?

Miller quotes newly-elected Republican senator, Marco Rubio, who offers this supercharged declaration of American exceptionalism: “Americans believe with all their heart, that the United States of America is simply the single greatest nation in all of human history, a place without equal in the history of all of mankind.”

Leave aside the fact that many Americans who hold this view have never actually visited another country, expressions of America’s exceptional character such as that by Rubio, represent a view of the world as much as one of America. Moreover, this is not merely about saying that America is unique but that it is superior to every other nation and that it must vigorously guard this position of supremacy.

If this was about praising a set of virtues, then one might imagine that those who see America in this way, would hope that every other nation might at some time share the same set of virtues. Clearly they do not hold this hope, because this is not about virtue or excellence — it is about power and domination. That America could be dislodged from its position of supremacy — this is the greatest fear of the supremacists.

In as much as American exceptionalism is rooted in a belief in American supremacy, then the power ascribed to the nation is implicitly shared by every American. That this is make-believe power is evident in the frequency and loudness with which it is declared and the fact that those who profess their conviction in this power nevertheless clearly easily feel threatened — threatened by the government; by the rest of the world; by immigrants; and by other Americans who don’t share their views.

And yet, the idea that the next presidential election will be a contest based on Americanism, is something that Democrats can justifiably fear. Even if Sarah Palin’s candidacy flops, this theme will be picked up by others as the cause of raw American nationalism easily resonates with a dispirited electorate.

As his victory speech made evident, Marco Rubio has an America-first message much harder to dismiss than Palin’s. The worst mistake of those who find this view of America unpalatable is to fail to take it seriously.

An empire decomposed: American foreign relations in the early 21st century

A must-read speech on the militarization of American diplomacy, by Chas Freeman, former US ambassador to Saudi Arabia, and the first casualty in the Israel lobby’s efforts to rein in what in its early days might have looked like a dangerously independent Obama administration.

Americans are accustomed to foreigners following us. After all, for forty years, we led the industrial democracies against the former USSR and its captive entourage. After the Soviet collapse, we bestrode the world as its sole colossus. For a while, we imagined we could do pretty much anything we wanted to do on our own. This, in the opinion of some, made followers irrelevant and leadership unnecessary.

Still, on reflection, we thought things might go better with a garland of allies and a garnish of friends. So we accepted some help from NATO members and some other foreign auxiliaries in Afghanistan. And, when we marched into the ambush of Iraq, we recruited a few other nations eager to ingratiate themselves with us to tag along in what became known as “the coalition of the billing.” In the end, however, in Iraq, it came down to us and our faithful British collaborators. Then, without even a “yo! Bush,” the Brits too were gone. And when we looked for other allies to follow us back into Afghanistan, they weren’t there.All this should remind us that power, no matter how immense, is not by itself enough to ordain leadership. Power must be informed by vision, guided by wisdom, and embodied in strategy if it is to inspire companions and followers. We’re a bit short of believers in our leadership these days, not just on the battlefields of West Asia but at global financial gatherings, the United Nations, meetings of the G-20, among human rights and environmental activists, in the world’s regions, including our own hemisphere, and so forth. There are few places where we Americans still enjoy the credibility and command the deference we once did. A year or so ago, we decided that military means were not always the best way to solve problems and that having diplomatic allies could really help do so. But it isn’t happening.

The excesses that brought about the wide-ranging devaluation of our global standing originate, I think, in our politically self-serving reinterpretation of the Cold War soon after it ended. As George Kennan predicted, the Soviet Union was eventually brought down by the infirmities of its system. The USSR thus lost its Cold War with America and our allies. We were still standing when it fell. They lost. We won, if only by default. Yet Americans rapidly developed the conviction that military prowess and Ronald Reagan’s ideological bravado — not the patient application of diplomatic and military “containment” to a gangrenous Soviet system — had brought us victory. Ours was a triumph of grand strategy in which a strong American military backed political and economic measures short of war to enable us to prevail without fighting. Ironically, however, our politicians came to portray this as a military victory. The diplomacy and alliance management that went into it were forgotten. It was publicly transmuted into a triumph based on the formidable capabilities of our military-industrial complex, supplemented by our righteous denunciation of evil.

Many things followed from this neo-conservative-influenced myth. One conclusion was the notion that diplomacy is for losers. If military superiority was the key to “victory” in the Cold War, it followed for many that we should bear any burden and pay any price to sustain that superiority in every region of the world, no matter what people in these regions felt about this. This was a conclusion that our military-industrial complex heard with approval. It had fattened on the Cold War but was beginning to suffer from enemy deprivation syndrome — that is, the disorientation and queasy apprehension about future revenue one gets when one’s enemy has irresponsibly dropped dead. With no credible enemy clearly in view, how was the defense industrial base to be kept in business? The answer was to make the preservation of global military hegemony our objective. With no real discussion and little fanfare, we did so. This led to increases in defense spending despite the demise of the multifaceted threat posed by the USSR. In other words, it worked.

Only a bit over sixty percent of our military spending is in the Department of Defense budget, with the rest hidden like Easter eggs in the nooks and crannies of other federal departments and agencies’ budgets. If you put it all together, however, defense-related spending comes to about $1.2 trillion, or about eight percent of our GDP. That is quite a bit more than the figure usually cited, which is the mere $685 billion (or 4.6 percent of GDP) of our official defense budget. Altogether, we spend more on military power than the rest of the world — friend or foe — combined. (This way we can be sure we can defeat everyone in the world if they all gang up on us. Don’t laugh! If we are sufficiently obnoxious, we might just drive them to it.) No one questions this level of spending or asks what it is for. Politicians just tell us it is short of what we require. We have embraced the cult of the warrior. The defense budget is its totem.

The rest of this speech can be read here. Thanks to War in Context reader Delia Ruhe for bringing this to my attention.

A presidential death warrant

American soldiers have to be trained how to kill, but for American presidents killing comes naturally.

Anyone who aspires to become president must surely ask themselves: am I willing to end someone else’s life, be that an individual or perhaps tens or hundreds of thousands or even millions of people? After all, even though it’s not spelled out in the Constitution, it’s clear that a pacifist could never hold this office. Killing comes with the territory.

Even so, I can’t help wondering when it was the Barack Obama posed this question and decided, “yes I can.”

With candidate George W Bush we didn’t need to ask the question. He had a track record — as the Governor of Texas he presided over 152 executions. But with Obama, we may never know when he came to regard killing as a tolerable part of his job.

It’s hard to imagine that as a community organizer he ever entertained the idea that wiping people out could become a dimension of working towards the greater good, yet at some point he must have seen this coming and — from all the evidence we now see — not flinched.

But to contrast Obama and Bush as killers, here’s what’s scary and yet passes without comment: Obama’s approach is dispassionate, with no explicit moral calculation. Whereas Bush felt driven to assume an air of righteousness and moral superiority, casting his actions within a drama of good and evil, Obama presents the image of an administrative process through which, after careful analysis and legal and political deliberation, lives are terminated.

Under the morally insidious rubric of “procedures” — a notion that peels away personal responsibility by replacing it with impersonal rules-based behavior — the president, the CIA, the military, the administration, the media, and the American public are all being offered an excuse to look the other way. An unnamed official assured a Washington Post reporter: “[there are] careful procedures our government follows in these kinds of cases.”

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target.

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target.

Representative Jane Harman, Democrat of California and chairwoman of a House subcommittee on homeland security, was out prepping the media and the public on Tuesday when she called Awlaki “probably the person, the terrorist, who would be terrorist No 1 in terms of threat against us.”

Although it was only this week that a US official announced that Awlaki is now on the CIA’s assassination list, US special forces were already authorized and had made at least one attempt to kill the Muslim cleric who now resides in Yemen.

While both the military and the CIA make use of drones for the purpose of remotely controlled assassination, the fact that Awlaki is now considered a legitimate target for “lethal CIA operations” raises questions about the methods the agency might use.

Last summer CIA Director Leon Panetta shut down a secret CIA program which would have operated assassination teams for hunting down al Qaeda leaders. The news was presented as though the new administration was again distancing itself from the questionable practices of the Bush administration, yet at the time, Director of National Intelligence Dennis C Blair told Congress that the termination of that particular program did not rule out the future use of insertion teams that could kill or capture terrorist leaders.

One of the many ironies here is that the Obama administration appears to have abandoned one of the Bush era rationales for torture in favor of its own rationale for murder.

The most frequently used justification for torturing terrorist suspects has been the claim that in the scenario of a so-called ticking time bomb, vital information might be forced out of a suspect enabling an imminent act of terrorism to be thwarted.

Anwar al-Awlaki is supposedly just such a suspect. “He’s working actively to kill Americans,” an American official told the Washington Post. But whatever vital intelligence he might be able to provide, we’ll probably never know. Once dead he won’t hatch any new plots, but as for the ones already set in motion, well, we’ll just have to wait and see what sort of surprises may yet appear.

Needless to say, I am not suggesting that torturing terrorist suspects is any more acceptable than murdering them.

Ken Gude, a human rights expert from the Center for American Progress, argues that Awlaki is a legitimate target for assassination because of his claimed role in assisting the 9/11 attackers. On that basis, his killing would appear to be an act of extra-judicial punishment rather than the removal of a potential threat. But even if the administration sticks assiduously to its focus on future threats, it should not claim a God-like power to predict the future. Nor should it assume that the threat someone poses is necessarily diminished once they are dead.

In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of Mohammed El Fazazi, a Moroccan cleric who from a Hamburg mosque preached to Mohammed Atta, Ramzi Binalshibh and Marwan al-Shehhi, three of the men who participated in the 9/11 attacks, that it was the duty of a devout Muslim to “slit the throats of non-believers.”

In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of Mohammed El Fazazi, a Moroccan cleric who from a Hamburg mosque preached to Mohammed Atta, Ramzi Binalshibh and Marwan al-Shehhi, three of the men who participated in the 9/11 attacks, that it was the duty of a devout Muslim to “slit the throats of non-believers.”

Eight years later, Fazazi had a new message as he appealed to Muslims to air their grievances through peaceful demonstrations. He is helping turn young men away from violent jihad. But what would stir the hearts of such men now if rather than hearing Fazazi’s moderated message, instead they held the memory of a day he became a martyr when struck by an American Hellfire missile?

Genuine American exceptionalism on due process

Glenn Greenwald on America’s disregard for due process:

If there’s any country which can legitimately claim that Islamic radicalism poses an existential threat to its system of government, it’s Pakistan. Yet what happens when they want to imprison foreign Terrorism suspects? They indict them and charge them with crimes, put them in their real court system, guarantee them access to lawyers, and can punish them only upon a finding of guilt. Pakistan is hardly the Beacon of Western Justice — its intelligence service has a long, clear and brutal record of torturing detainees (and these particular suspects claim they were jointly tortured by Pakistani agents and American FBI agents, which both governments deny). But just as is true for virtually every Western nation other than the U.S., Pakistan charges and tries Terrorism suspects in its real court system.

The U.S. — first under the Bush administration and now, increasingly, under Obama — is more and more alone in its cowardly insistence that special, new tribunals must be invented, or denied entirely, for those whom it wishes to imprison as Terrorists (along those same lines, my favorite story of the last year continues to be that the U.S. compiled a “hit list” of Afghan citizens it suspected of drug smuggling and thus wanted to assassinate [just as we do for our own citizens suspected of Terrorism], only for Afghan officials — whom we’re there to generously teach about Democracy — to object on the grounds that the policy would violate their conceptions of due process and the rule of law). Most remarkably, none of this will even slightly deter our self-loving political and media elites from continuing to demand that the Obama administration act as self-anointed International Arbiter of Justice and lecture the rest of the world about their violations of human rights.

The myth of “America”

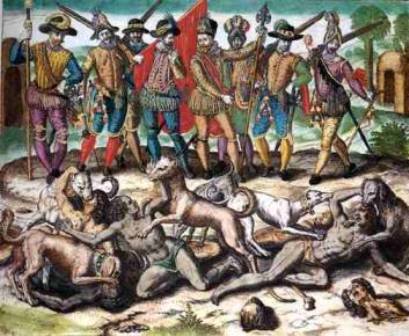

Catholic priest Bartolome de las Casas, in the multi-volume “History of the Indies” published in 1875, wrote, “… Slaves were the primary source of income for the Admiral (Columbus) with that income he intended to repay the money the Kings were spending in support of Spaniards on the Island. They provide profit and income to the Kings. (The Spaniards were driven by) insatiable greed … killing, terrorizing, afflicting, and torturing the native peoples … with the strangest and most varied new methods of cruelty.”

This systematic violence was aimed at preventing “Indians from daring to think of themselves as human beings. (The Spaniards) thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades…. My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature, and now I tremble as I write.”

This systematic violence was aimed at preventing “Indians from daring to think of themselves as human beings. (The Spaniards) thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades…. My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature, and now I tremble as I write.”

Father Fray Antonio de Montesino, a Dominican preacher, in December 1511 said this in a sermon that implicated Christopher Columbus and the colonists in the genocide of the native peoples:

“Tell me by what right of justice do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged such detestable wars against these people who dealt quietly and peacefully on their own lands? Wars in which you have destroyed such an infinite number of them by homicides and slaughters never heard of before …”

In 1892, the National Council of Churches, the largest ecumenical body in the United States, is known to have exhorted Christians to refrain from celebrating the Columbus quincentennial, saying, “What represented newness of freedom, hope, and opportunity for some was the occasion for oppression, degradation and genocide for others.”

Yet America continues to celebrate “Columbus Day.” [continued…]

NEWS & OPINION: Overcoming America’s fear of the world

I never thought I’d be in this position. There’s a debate taking place about what matters most when making judgments about foreign policy— experience and expertise on the one hand, or personal identity on the other. And I find myself coming down on the side of identity.

Throughout the campaign, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton have been squabbling over who has the better qualifications to lead the world’s only superpower.

Hillary’s case is obvious and perfectly defensible. She’s been involved in foreign policy for eight years in the White House (though in a sideways fashion as First Lady) and then seven years as a senator. Most of the Democratic Party’s blue-chip foreign-policy advisers support her. Plus, she has Bill.

Obama’s argument is about more than identity. He was intelligent and prescient about the costs of the Iraq War. But he says that his judgment was formed by his experience as a boy with a Kenyan father—and later an Indonesian stepfather—who spent four years growing up in Indonesia, and who lived in the multicultural swirl of Hawaii.

I never thought I’d agree with Obama. I’ve spent my life acquiring formal expertise on foreign policy. I’ve got fancy degrees, have run research projects, taught in colleges and graduate schools, edited a foreign-affairs journal, advised politicians and businessmen, written columns and cover stories, and traveled hundreds of thousands of miles all over the world. I’ve never thought of my identity as any kind of qualification. I’ve never written an article that contains the phrase “As an Indian-American …” or “As a person of color …”

But when I think about what is truly distinctive about the way I look at the world, about the advantage that I may have over others in understanding foreign affairs, it is that I know what it means not to be an American. [complete article]

Strictures in U.S. prompt Arabs to study elsewhere

A generation of Arab men who once attended college in the United States, and returned home to become leaders in the Middle East, increasingly is sending the next generation to schools elsewhere. This year, Australia overtook the United States as the top choice of citizens of the United Arab Emirates heading abroad for college, according to government figures here.

Ten percent fewer students in the Emirates elected to go to the United States in 2006 than in 2005, according to the New York-based Institute of International Education.

In neighboring Oman, the drop was 25 percent. Jordan, Kuwait and Lebanon recorded single-digit falls, continuing a trend begun amid the crackdowns on visas and security that followed the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. [complete article]

FBI prepares vast database of biometrics

The FBI is embarking on a $1 billion effort to build the world’s largest computer database of peoples’ physical characteristics, a project that would give the government unprecedented abilities to identify individuals in the United States and abroad.

Digital images of faces, fingerprints and palm patterns are already flowing into FBI systems in a climate-controlled, secure basement here. Next month, the FBI intends to award a 10-year contract that would significantly expand the amount and kinds of biometric information it receives. And in the coming years, law enforcement authorities around the world will be able to rely on iris patterns, face-shape data, scars and perhaps even the unique ways people walk and talk, to solve crimes and identify criminals and terrorists. The FBI will also retain, upon request by employers, the fingerprints of employees who have undergone criminal background checks so the employers can be notified if employees have brushes with the law. [complete article]

NEWS, OPINION & EDITOR’S COMMENT: Moral clarity on torture

CIA spy calls waterboarding necessary but torture

A leader of the CIA team that captured the first major al Qaeda figure, Abu Zubaydah, says subjecting him to waterboarding was torture but necessary.

In the first public comment by any CIA officer involved in handling high-value al Qaeda targets, John Kiriakou, now retired, said the technique broke Zubaydah in less than 35 seconds.

“The next day, he told his interrogator that Allah had visited him in his cell during the night and told him to cooperate,” said Kiriakou in an interview to be broadcast tonight on ABC News’ “World News With Charles Gibson” and “Nightline.”

“From that day on, he answered every question,” Kiriakou said. “The threat information he provided disrupted a number of attacks, maybe dozens of attacks.” [complete article]

Editor’s Comment — “Because we’re Americans, and we’re better than that” — it’s a popular line, a curious quasi-ethical principal, and it’s John Kiriakou’s reason for no longer supporting the use of torture.

American ideals might be better than that, but Americans and their ideals are not the same. The American government sanctioned torture and American CIA officers have engaged in torture. Therein lies one of the many gaps between America and its ideals.

But to debate the issue of torture in terms of whether it is or is not un-American is to obscure a moral question that is not as complex as it is being made to appear. The issue should not hinge on whether we accept an idealized conception of what it means to be American. It has nothing to do with national identity. It hinges quite simply on whether we accept or reject the principle that the ends justifies the means.

Any time the phrase “saving American lives” enters the torture debate an ends-justifies-the-means argument is being employed. At the same time, no one actually wants to positively assert this line of reasoning. If the ends really do justifies the means then it shouldn’t make any difference what those means are — pulling out finger nails, raping relatives — why would anything be off limits if it could be shown to be effective in saving American lives?

On the other side is a pragmatic (and seemingly safe) argument: torture shouldn’t be used because it doesn’t work. It yields false confessions and there are much better non-violent means to tease out valuable information. This is also a means-ends argument that merely challenges the assumption that the means will accomplish the aims. (And not only is it a means-ends argument; it’s also rather easy to counter. All you have to do is present a case — as the CIA has just done — where it appears that torture “worked.”)

And then there’s the question of who gets tortured. To cite evidence that Abu Zubaydah may not have been a high-level al Qaeda operative is to imply that the legitimacy of torture is affected by the potential for the victim to cough up some valuable information. In other words, it implies that torture might be justifiable if it can be demonstrated that this particular person is really “worth” torturing. (Again, the CIA — on behalf of Bush-Cheney — presses the case that it has been extremely selective in who gets tortured.)

Ultimately, the only unambiguous moral position to take is to say that a calculated effort to make a human being suffer is immoral – it doesn’t make any difference who that person is or how well-intentioned the torturer might be. That’s moral clarity and that’s the principle that law and policy should embody.

The torture of Abdul Hamid al-Ghizzawi

On December 7, 2006, he was among several hundred detainees randomly selected and moved to the newest detention camp at Guantanamo, Camp 6, which was designed to hold the majority of the detainees. According to Amnesty International, and in contravention of international standards, all detainees in Camp 6 are held under conditions of “extreme isolation and sensory deprivation for a minimum of 22 hours a day in individual steel cells with no windows to the outside.”

Their cells reportedly are extremely small. The only source of light is fluorescent lighting that is on 24 hours a day and the only air is air-conditioning, both of which are controlled by the prison guards. The detainees reportedly are allowed two hours of “recreation time” a day to be spent in a metal cage measuring four feet by four feet. (That’s 1/3 the size of a ping-pong table.)

Al-Ghizzawi’s lawyer says that his guards frequently give him his “rec time” in the middle of the night or, sometimes, in the middle of the day when the cage is in the hot sun. Detainees in Camp 6 have no access to radio, television or newspapers. They are given one book a week.

According to his lawyer, Al-Ghizzawi’s eyesight has deteriorated so significantly that he is now unable to read. Thus he now spends his time pacing in his cell. All of the detainees at Guantanamo reportedly are forbidden telephone calls and family visits, and most are not allowed to touch another human being. The detainees are not given any blankets. Their only cover is a plastic sheet.

There is no reason to believe that Al-Ghizzawi’s treatment is exceptional. If his is at all an exceptional case, it is exceptional because he has twice been unanimously declared not to be an enemy combatant. [complete article]

The footage was blurry, shot with a handheld 8mm camera in the poor light filtering through the shack’s small windows. There was no sound—which lent merciful distance to what it showed: the interrogation of some unidentified middle-aged man, undergoing falanga, mostly (beatings to pulp the feet), though the session culminated in anal rape with a stick. What remains as a true horror in the memory is less those activities than the demeanor of the inquisitors. A couple of men in shirts were administering the torture. But a pair of interrogators stood off to one side, mostly out of the frame. They came to the victim before and after each bout, evidently asking questions. Then they’d go back out of frame, to let the next round of beatings commence. Two men in neat dark suits, professionals, just doing a job—unpleasant, perhaps, but necessary, as they saw it, for the safety of the state.

That no doubt is the true horror of the tapes the CIA destroyed—worse, even, than the sight of the torture procedures themselves. We assume it shows waterboarding, the near-drowning of someone strapped to a cruciform plank. Memories of that Savak instructional film tell me, indelibly, what the videos would have looked like: the torturers calmly pouring water over the cloth covering the victims’ faces, the frenzied chest-heavings as the bodies went into shock, the gasping and retching as each session ended. More horrifying still would have been the actions, or inactions, of all those standing around. There must have been interrogators, and an interpreter. Certainly a doctor, watching the victims’ vital signs on a monitor to gauge how long each session could last. This being America, there may have even been a lawyer on hand. All professionals, doing something unpleasant, but—you understand—necessary for the safety of the state. And at the end of the day, one assumes, they drove home to their families.

This is where 9/11 has brought us. No wonder Rodriguez destroyed those tapes. [complete article]

Lawyers cleared destroying tapes

Lawyers within the clandestine branch of the Central Intelligence Agency gave written approval in advance to the destruction in 2005 of hundreds of hours of videotapes documenting interrogations of two lieutenants from Al Qaeda, according to a former senior intelligence official with direct knowledge of the episode.

The involvement of agency lawyers in the decision making would widen the scope of the inquiries into the matter that have now begun in Congress and within the Justice Department. Any written documents are certain to be a focus of government investigators as they try to reconstruct the events leading up to the tapes’ destruction.

The former intelligence official acknowledged that there had been nearly two years of debate among government agencies about what to do with the tapes, and that lawyers within the White House and the Justice Department had in 2003 advised against a plan to destroy them. But the official said that C.I.A. officials had continued to press the White House for a firm decision, and that the C.I.A. was never given a direct order not to destroy the tapes.

“They never told us, ‘Hell, no,’” he said. “If somebody had said, ‘You cannot destroy them,’ we would not have destroyed them.” [complete article]

Editor’s Comment — Any decent mafia boss knows how to avoid implicating himself in a crime.

See also, Gitmo inmate’s lawyer urges U.S. on photos (AP).

OPINION: A candidate for the world

Little that is certain can be said about the U.S. election a year from now, but one certainty is this: about 6.3 billion people will not be voting even if they will be affected by the outcome.

That’s the approximate world population outside the United States. If nothing else, President Bush has reminded them that it’s hard to get out of the way of U.S. power. The wielding of it, as in Iraq, has whirlwind effects. The withholding of it, as on the environment, has a huge impact.

No wonder the view is increasingly heard that everyone merits a ballot on Nov. 4, 2008.

That won’t happen, of course. Even the most open-armed multilateralist is not ready for hanging chads in Chad. But the broader point of the give-us-a-vote itch must be taken: the global community is ever more linked. American exceptionalism, as practiced by Bush, has created a longing for new American engagement.

Renewal is about policy; it’s also about symbolism. Which brings us to Barack Hussein Obama, the Democratic candidate with a Kenyan father, a Kansan mother, an Indonesian stepfather, a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia and impressionable experience of the Muslim world.

If the globe can’t vote next November, it can find itself in Obama. Troubled by the violent chasm between the West and the Islamic world? Obama seems to bridge it. Disturbed by the gulf between rich and poor that globalization spurs? Obama, the African-American, gets it: the South Side of Chicago is the South Side of the world. [complete article]

NEWS, OPINION & EDITOR’S COMMENT: An American awakening?

Picking up after failed war on terror

Given that Bush’s version of global war has proved such a costly flop, what ought to replace it? Answering that question requires a new set of principles to guide U.S. policy. Here are five:

* Rather than squandering American power, husband it. As Iraq has shown, U.S. military strength is finite. The nation’s economic reserves and diplomatic clout also are limited. They badly need replenishment.

* Align ends with means. Although Bush’s penchant for Wilsonian rhetoric may warm the cockles of neoconservative hearts, it raises expectations that cannot be met. Promise only the achievable.

* Let Islam be Islam. The United States possesses neither the capacity nor the wisdom required to liberate the world’s 1.4 billion Muslims, who just might entertain their own ideas about what genuine freedom entails. Islam will eventually accommodate itself to the modern world, but Muslims will have to work out the terms.

* Reinvent containment. The process of negotiating that accommodation will produce unwelcome fallout: anger, alienation, scapegoating and violence. In collaboration with its allies, the United States must insulate itself against Islamic radicalism. The imperative is not to wage global war, whether real or metaphorical, but to erect effective defenses, as the West did during the Cold War.

* Exemplify the ideals we profess. Rather than telling others how to live, Americans should devote themselves to repairing their own institutions. Our enfeebled democracy just might offer the place to start.

The essence of these principles can be expressed in a single word: realism, which implies seeing ourselves as we really are and the world as it actually is. [complete article]

Editor’s Comment — “Seeing ourselves as we really are and the world as it actually is” — yes indeed, wouldn’t that be a welcome change? But it would also amount to a profound transformation in the American psyche.

Few people in the world have a realistic self-image — what distinguishes Americans is that their lack of self-understanding has such a destructive impact on others.

As occupants of a continent with vast oceans to either side, there is a geographic realism to America’s sense of isolation. The gulf that now needs to be crossed is psychological — it requires that Americans acquire the conviction that the world matters. Yet the world as “other” — as somewhere else — is something from which we have set ourselves apart. Having distasterously ventured into this other, discovered that we are often unwelcome and even reviled, the natural response is to retreat.

The pompous advocates of engagement assert that the world needs American leadership. The message that Americans and the world really need to hear is the reverse: America needs the world. We cannot afford to isolate ourselves. We cannot afford to remain ignorant. The world that seems other is simply a world in which we have yet to understand our place. It is a world in which we should neither assert preeminence nor project our fear.

Next president urged to fix global image

The next US president must expand American involvement in the United Nations and other international bodies and dramatically increase foreign aid – especially among Muslim countries – to reverse the steep decline in American influence and enhance national security, a bipartisan group of politicians, business executives, and academics said in a report yesterday.

more stories like this

The report, titled “A Smarter and Safer America,” also condemned what it called the American “exporting of fear” since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, and criticized the use of “hard power,” military might, as the main component of US foreign policy instead of the “soft power” of positive US influences.

But the authors – including Richard Armitage, former deputy secretary of state under President Bush, retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and Harvard professor Joseph S. Nye Jr. – said their recommendations, issued one year ahead of Election Day, is a foreign policy blueprint for Democratic and Republican presidential hopefuls. [complete article]

NEWS: Romney: “A world without America as the leader is a very frightening place”

Mitt Romney: I won’t let U.S. go the way of U.K.

The United States is in danger of becoming a “second-tier” nation like Britain and other European countries if Hillary Clinton wins the White House, according to Mitt Romney, the Republican presidential contender.

Although he gave a Hallowe’en warning of a “house of horrors” if Mrs Clinton is elected, the main bogeyman for the former Massachusetts governor’s stump has become Europe, with Britain’s national health service being singled out for special mention.

Speaking, ironically, to employees of BAE Systems Inc, the US subsidiary of the British defence company, in the elegant New England town of Nashua on Monday, Mr Romney said that America was at a crossroads in history.

“The question is whether we’re going to become a stronger nation leading the world or whether we’re going to follow the path of Europe and become a second-tier military and a second-tier nation.” European countries had chosen to “become a wonderful nation but not the world’s power”.

America’s health system should remain privately rather than government run, he insisted. “I do not want to go the way of England and Canada when it comes to healthcare,” he said.

He added: “For me what America should do is strengthen our military, strengthen our economy and strengthen our family structure so that we always remain the most powerful nation on earth. A world without America as the leader is a very frightening place.” [complete article]

OPINION & EDITOR’S COMMENT: America’s shadow

We can continue to blame the Bush administration for the horrors of Iraq — and should. Paul Bremer, our post-invasion viceroy and the recipient of a Presidential Medal of Freedom for his efforts, issued the order that allows contractors to elude Iraqi law, a folly second only to his disbanding of the Iraqi Army. But we must also examine our own responsibility for the hideous acts committed in our name in a war where we have now fought longer than we did in the one that put Verschärfte Vernehmung on the map.

I have always maintained that the American public was the least culpable of the players during the run-up to Iraq. The war was sold by a brilliant and fear-fueled White House propaganda campaign designed to stampede a nation still shellshocked by 9/11. Both Congress and the press — the powerful institutions that should have provided the checks, balances and due diligence of the administration’s case — failed to do their job. Had they done so, more Americans might have raised more objections. This perfect storm of democratic failure began at the top.

As the war has dragged on, it is hard to give Americans en masse a pass. We are too slow to notice, let alone protest, the calamities that have followed the original sin. [complete article]

Editor’s Comment — As Frank Rich notes:

It was always the White House’s plan to coax us into a blissful ignorance about the war. Part of this was achieved with the usual Bush-Cheney secretiveness, from the torture memos to the prohibition of photos of military coffins. But the administration also invited our passive complicity by requiring no shared sacrifice. A country that knows there’s no such thing as a free lunch was all too easily persuaded there could be a free war.

Yet what is missing in these observations about the multiple ways in which our humanity has been compromised, is an acknowledgment of the degree to which the administration’s policies have been buttressed by a current in American politics and across American culture that provided the bedrock for America’s response to 9/11, namely, xenophobia. This isn’t xenophobia that was triggered by 9/11; it was an already prevailing sentiment that the Bush administration could easily harness in support of its policies.

When GOP presidential candidate, Mitt Romney, recently said, “we ought to double Guantanamo,” he wasn’t sticking his neck out; he knew he was appealing not only to his base but to also to those xenophobic Democrats who fear that a liberal in the White House might make America more vulnerable to the foreign threat.

And when last year the controversy blew up over the outsourcing of US port management to Dubai’s DP World, Democrats in Congress didn’t hesitate to jump on the xenophobic bandwagon.