Category Archives: democracy

America is NOT broke

Michael Moore, speaking yesterday in Madison, Wisconsin:

Contrary to what those in power would like you to believe so that you’ll give up your pension, cut your wages, and settle for the life your great-grandparents had, America is not broke. Not by a long shot. The country is awash in wealth and cash. It’s just that it’s not in your hands. It has been transferred, in the greatest heist in history, from the workers and consumers to the banks and the portfolios of the uber-rich.

Right now, this afternoon, just 400 Americans have more wealth than half of all Americans combined.

Let me say that again — and please, someone in the mainstream media, just repeat this fact once. We’re not greedy. We’ll be happy to just hear it once: 400 obscenely wealthy individuals — 400 little Mubaraks — most of whom benefited in some way from the multi-trillion dollar taxpayer “bailout” of 2008, now have more cash, stock and property than the assets of 155 million Americans combined.

[Crowd chants: Shame! Shame! Shame!]

If you can’t bring yourself to call that a financial coup d’état, then you are simply not being honest about what you know in your heart to be true.

And I can see why. For us to admit that we have let a small group of men abscond with and hoard the bulk of the wealth that runs our economy, would mean that we’d have to accept the humiliating acknowledgment that we have indeed surrendered our precious Democracy to the moneyed elite. Wall Street, the banks and the Fortune 500 now run this Republic — and, until this past month here in Madison Wisconsin, the rest of us have felt completely helpless, unable to find a way to do anything about it.

Michael Moore: a war against the middle class in Wisconsin

Arming democracy’s opponents

The Daily Telegraph reports:

Facing budget cuts at home, western arms firms are desperate for a share of the lucrative Middle East market. “The post-financial crisis reality,” said Herve Guillou, president of Cassidian Systems, a subsidiary of European aviation defence group EADS, “is that today it is clearly the Middle East that is seeing the biggest growth.” Iran’s growing military power has pushed Gulf states into their largest-ever military build up, making purchases worth £76 billion from the US alone in 2010. The largest acquisitions were made by Saudi Arabia, which is spending £41 billion on F-15 fighter jets and upgrades for its naval fleet.

The six Gulf Cooperation Council countries – Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, UAE, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait – along with Jordan will spend another £41 billion on defence in 2011, according to Frost and Sullivan, a research firm.

Libya and Egypt are among the states which have representatives at IDEX [the International Defence Exhibition and Conference in Abu Dhabi]. Global Industrial and Defence Solutions, a Pakistani exhibitor, lists Libya as being among the “key customers of our products.” Renault also issued a press release before the exhibition, saying it had contracted to supply military trucks to Egypt. Libya’s al-Musallah magazine, which covers arms-trade related issues in the country, is also among the exhibitors.

Simon Jenkins writes:

I must be missing something. The present British government, like its predecessor, claims to pursue a policy of “liberal interventionism”, seeking the downfall of undemocratic regimes round the globe, notably in the Muslim world. The same British government, again like its predecessor, sends these undemocratic regimes copious weapons to suppress the only plausible means of the said downfall, popular insurrection. The contradiction is glaring.

Downing Street is clearly embarrassed by Egypt, Bahrain and Libya having had the impertinence to rebel just as David Cameron was embarking on an important arms-sales trip to the Gulf, not an area much addicted to democracy. Fifty British arms makers were present at last year’s sickening Libyan arms fair, while the resulting weapons are reportedly prominent in gunning down this week’s rioters. Cameron reads from the Foreign Office script, claiming that all guns, tanks, armoured vehicles, stun grenades, tear gas and riot-control equipment are “covered by assurances that they would not be used in human rights repression”. He must know this is absurd.

What did the FO think Colonel Gaddafi meant to do with sniper rifles and tear-gas grenades – go mole hunting? Britain has tried to cover its publicity flank by “revoking 52 export licences” to Bahrain and Libya for weapons used against demonstrators, in effect admitting its guilt. This merely locks the moral stable after the horse has fled, while also being a poor advertisement for British after-sales service. What is the point of selling someone a gun and telling him not to use it?

Gaddafi turns US and British guns on his own people

Gaddafi cruelly resists, but this Arab democratic revolution is far from over

In agreement with Gilles Kepel who has dubbed events unfolding across the Middle East as the “Arab democratic revolution,” David Hirst writes:

[S]ome now say, this emergence of democracy as an ideal and politically mobilising force amounts to nothing less than a “third way” in modern Arab history. The first was nationalism, nourished by the experience of European colonial rule and all its works, from the initial great carve-up of the “Arab nation” to the creation of Israel, and the west’s subsequent, continued will to dominate and shape the region. The second, which only achieved real power in non-Arab Iran, was “political Islam”, nourished by the failure of nationalism.

And it is doubly revolutionary. First, in the very conduct of the revolution itself, and the sheer novelty and creativity of the educated and widely apolitical youth who, with the internet as their tool, kindled it. Second, and more conventionally, in the depth, scale and suddenness of the transformation in a vast existing order that it seems manifestly bound to wreak.

Arab, yes – but not in the sense of the Arabs going their own away again. Quite the reverse. No other such geopolitical ensemble has so long boasted such a collection of dinosaurs, such inveterate survivors from an earlier, totalitarian era; no other has so completely missed out on the waves of “people’s power” that swept away the Soviet empire and despotisms in Latin America, Asia and Africa. In rallying at last to this now universal, but essentially western value called democracy, they are in effect rejoining the world, catching up with history that has left them behind.

If it was in Tunis that the celebrated “Arab street” first moved, the country in which – apart from their own – Arabs everywhere immediately hoped that it would move next was Egypt. That would amount to a virtual guarantee that it would eventually come to them all. For, most pivotal, populous and prestigious of Arab states, Egypt was always a model, sometimes a great agent of change, for the whole region. It was during the nationalist era, after President Nasser’s overthrow of the monarchy in 1952, that it most spectacularly played that role. But in a quieter, longer-term fashion, it was also the chief progenitor, through the creation of the Muslim Brotherhood, of the “political Islam” we know today, including – in both the theoretical basis as well as substantially in personnel – the global jihad and al-Qaida that were to become its ultimate, deviant and fanatical descendants.

But third, and most topically, it was also the earliest and most influential exemplar of the thing which, nearly 60 years on, the Arab democratic revolution is all about. Nasser did seek the “genuine democracy” that he held to be best fitted for the goals of his revolution. But, for all its democratic trappings, it was really a military-led, though populist, autocracy from the very outset; down the years it underwent vast changes of ideology, policy and reputation, but, forever retaining its basic structures, it steadily degenerated into that aggravated, arthritic,deeply oppressive and immensely corrupt version of its original self over which Hosni Mubarak presided. With local variations, the system replicated itself in most Arab autocracies, especially the one-time revolutionary ones like his, but in the older, traditional monarchies too.

And, sure enough, Egypt’s “street” did swiftly move, and in nothing like the wild and violent manner that the image of the street in action has always tends to conjure up in anxious minds. As a broad and manifestly authentic expression of the people’s will, it accomplished the first, crucial stage of what surely ranks as one of the most exemplary, civilised uprisings in history. The Egyptians feel themselves reborn, the Arab world once more holds Egypt, “mother of the world”, in the highest esteem. And finally – after much artful equivocation as they waited to see whether the pharaoh, for 30 years the very cornerstone of their Middle East, had actually fallen – President Obama and others bestowed on them the unstinting official tributes of the west.

These plaudits raise the great question: if the Arabs are now rejoining the world what does it mean for the world? Will the adoption of a fundamental western value make it necessarily receptive to western policies or prescriptions? Probably not. Democracy itself, let alone Arab resentment over the west’s long record of upholding the old, despotic order, will militate against that.

Secular intifadas

Robert Fisk writes:

Mubarak claimed that Islamists were behind the Egyptian revolution. Ben Ali said the same in Tunisia. King Abdullah of Jordan sees a dark and sinister hand – al-Qa’ida’s hand, the Muslim Brotherhood’s hand, an Islamist hand – behind the civil insurrection across the Arab world. Yesterday the Bahraini authorities discovered Hizbollah’s bloody hand behind the Shia uprising there. For Hizbollah, read Iran. How on earth do well-educated if singularly undemocratic men get this thing so wrong? Confronted by a series of secular explosions – Bahrain does not quite fit into this bracket – they blame radical Islam. The Shah made an identical mistake in reverse. Confronted by an obviously Islamic uprising, he blamed it on Communists.

Bobbysocks Obama and Clinton have managed an even weirder somersault. Having originally supported the “stable” dictatorships of the Middle East – when they should have stood by the forces of democracy – they decided to support civilian calls for democracy in the Arab world at a time when the Arabs were so utterly disenchanted with the West’s hypocrisy that they didn’t want America on their side. “The Americans interfered in our country for 30 years under Mubarak, supporting his regime, arming his soldiers,” an Egyptian student told me in Tahrir Square last week. “Now we would be grateful if they stopped interfering on our side.” At the end of the week, I heard identical voices in Bahrain. “We are getting shot by American weapons fired by American-trained Bahraini soldiers with American-made tanks,” a medical orderly told me on Friday. “And now Obama wants to be on our side?”

The events of the past two months and the spirit of anti-regime Arab insurrection – for dignity and justice, rather than any Islamic emirate – will remain in our history books for hundreds of years. And the failure of Islam’s strictest adherents will be discussed for decades. There was a special piquancy to the latest footage from al-Qa’ida yesterday, recorded before the overthrow of Mubarak, that emphasised the need for Islam to triumph in Egypt; yet a week earlier the forces of secular, nationalist, honourable Egypt, Muslim and Christian men and women, had got rid of the old man without any help from Bin Laden Inc. Even weirder was the reaction from Iran, whose supreme leader convinced himself that the Egyptian people’s success was a victory for Islam. It’s a sobering thought that only al-Qa’ida and Iran and their most loathed enemies, the anti-Islamist Arab dictators, believed that religion lay behind the mass rebellion of pro-democracy protesters.

Adam Shatz writes:

After the battle for Tahrir Square, the conceptual grid that Western officials have used to divide the Islamic world into friends and enemies, moderates and radicals, good Muslims and bad Muslims has never looked more inadequate, or more irrelevant. A ‘moderate’ and ‘stable’ Arab government, a pillar of US strategy in the Middle East, has been overthrown by a nationwide protest movement demanding democratic reform, transparent governance, freedom of assembly, a more equitable distribution of the country’s resources and a foreign policy more reflective of popular opinion. It has sent other Arab governments into a panic while raising the hopes of their young, frustrated populations. If the revolution in Egypt succeeds, it will have swept away not only a corrupt and autocratic regime, but the vocabulary, and the patterns of thought, that have underpinned Western policy in the greater Middle East for more than a half century.

The fate of Egypt’s revolution – brought to a pause by the military’s seizure of power on 11 February, after Mubarak’s non-resignation address to his ‘children’ – remains uncertain. Mubarak is gone, but the streets have been mostly cleared of protesters and the army has filled the vacuum: chastened, yet still in power and with considerable resources at its disposal. Until elections are held in six months, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces will be ruling by decree, without the façade of parliamentary government. The parliament, voted into office in rigged elections, has been dissolved, a move that won wide support, and a new constitution is being drafted, but it’s not clear how much of a hand the opposition will have in shaping it. More ominously, the Supreme Council has vowed to punish anyone it can accuse of spreading ‘chaos and disorder’. The blunt rhetoric of its communiqués may be refreshing after the speeches of Mubarak, his son Gamal and the industrialists who dominated the ruling National Democratic Party, with their formulaic promises of reform and their talk of the nobility of the Egyptian people but ten days ago in Tahrir Square the protesters said – maybe even believed – that the army and the people stood together. Today the council’s communiqués are instructions, not proposals to be debated, and it has notably failed to answer the protesters’ two most urgent demands: the repeal of the Emergency Law and the release of thousands of political prisoners.

Nathan Brown writes:

The Egyptian revolution has captivated audiences and inspired a sense of endless new possibilities. Whether it is a “new dawn” or “a dividing point in history” (as I heard it described by Jordanians and Palestinians across the political spectrum), Egyptians are seen as having brought down a rotten system as they begin to write their own future. The only question is how other Arabs (and maybe even Iranians) can join them.

I am not yet so sure.

It is not that the old regime still remains (though it does; the junta and the cabinet are both still staffed by pre-revolutionary appointees and only vague hints of a cabinet reshuffle have been floated). It is clear that real change of some kind will take place. But the shape of the transition has not yet been defined. A more democratic, pluralistic, participatory, public-spirited, and responsive political system is a real possibility. But so is a kinder, gentler, presidentially-dominated, liberalized authoritarianism. In this post, I will discuss the state of play in Egypt; in future writings I hope to explore the implications for other regimes in the region.

The danger of indefinite military rule in Egypt is small. While pundits have often proclaimed the military to be the real political power in Egypt since 1952, in fact the political role for the military has been restricted for a generation. And there is no sign that the junta wants to change that for long. It is order, not power that they seem to seek. When the generals suspended the constitution, most opposition elements saw that as a positive step because it made possible far-reaching change, and I think that was a correct political judgment. (The suspension led to odd headlines in international press referring to Egypt as now being under martial law. But Egypt has been under martial law with only brief interruptions since 1939. It was not the generals who placed Egypt under martial law; that step was taken by King Faruq.)

But if the suspension of the constitution allowed the possibility of fundamental change, it did not require it. Indeed, the transition as defined by Egypt’s junta seems both extremely rushed and very limited.

Associated Press reports:

He organized his first demonstration while still a student in 1998, then got arrested and tortured by Egyptian police two years later at age 23. Now he has seen the fall of the president he spent his adult life struggling against.

For 33-year-old activist Hossam el-Hamalawy, though, Egypt’s three-week youth revolution is by no means over — there remains a repressive state to be dismantled and workers who need to get their rights.

“The job is unfinished, we got rid of (Hosni) Mubarak but we didn’t get rid of his dictatorship, we didn’t get rid of the state security police,” he told The Associated Press while sipping strong Arabic coffee in a traditional downtown cafe that weeks before had been the scene of street battles.

The activism career of el-Hamalawy typifies the long, and highly improbable, trajectory of the mass revolt that ousted Mubarak, Egypt’s long-entrenched leader. Once a dreamer organizing more or less on his own, el-Hamalawy’s dreams suddenly hardened into reality. The next step, he says, is the Egyptian people must press their advantage.

“This is phase two of the revolution,” said el-Hamalawy, who works as a journalist for an English-language online Egyptian paper and runs the Arabawy blog, a clearing house for information on the country’s fledgling independent labor movement — a campaign that has become increasingly assertive since the fall of the old government.

For years, activists in Egypt planted seeds — sometimes separately, sometimes in coordination — building networks and pushing campaigns on specific causes. They fought lonely fights: anti-war protests here, labor strikes there, an effort to raise awareness about police abuse, another to organize “Keep Our City Clean” trash collection.

Then one day in late January, it all came together for them. They were part of a movement, hundreds of thousands strong.

For three weeks, el-Hamalawy fought regime supporters and manned the barricades in Tahrir Square, but unlike the youth leaders who have come to prominence in the aftermath of the uprising, he refuses to talk to the generals now ruling Egypt and fears the uprising’s momentum is being lost as everyone waits for the military to transition the country to a new government.

Who gave the order to kill at Pearl Roundabout?

When Bahrain’s army opened fire on unarmed protesters yesterday there was little reason to suppose that this was anything other than a cold and calculated show of force. The lesson from Cairo for many Arab leaders was that a regime that is timid about killing its own people will quickly fall. Political dissent cannot be crushed by thugs marauding on camels and horses. The decisive message comes as a government’s marksman steadies his sight with a protester’s head fixed in the cross-hairs. There was nothing random about this act of violence:

But then comes the stunningly eloquent Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, expressing remorse about the tragic events of recent days.

Are we to supposed that an army captain at Pearl Roundabout was responsible for yesterday’s bloodshed. Or was it that Crown Prince Salman’s consternation was not in response to recklessness in the lower ranks but because the Al Khalifa royal family was under pressure from a higher level?

Robert Fisk reports:

Rumours burned like petrol in Bahrain yesterday and many medical staff were insisting that up to 60 corpses had been taken from Pearl Square on Thursday morning and that police were seen by crowds loading bodies into three refrigerated trucks. One man showed me a mobile phone snapshot in which the three trucks could be seen clearly, parked behind several army armoured personnel carriers. According to other demonstrators, the vehicles, which bore Saudi registration plates, were later seen on the highway to Saudi Arabia. It is easy to dismiss such ghoulish stories, but I found one man – another male nurse at the hospital who works under the umbrella of the United Nations – who told me that an American colleague, he gave his name as “Jarrod”, had videotaped the bodies being put into the trucks but was then arrested by the police and had not been seen since.

Why has the royal family of Bahrain allowed its soldiers to open fire at peaceful demonstrators? To turn on Bahraini civilians with live fire within 24 hours of the earlier killings seems like an act of lunacy.

But the heavy hand of Saudi Arabia may not be far away. The Saudis are fearful that the demonstrations in Manama and the towns of Bahrain will light equally provocative fires in the east of their kingdom, where a substantial Shia minority lives around Dhahran and other towns close to the Kuwaiti border. Their desire to see the Shia of Bahrain crushed as quickly as possible was made very clear at Thursday’s Gulf summit here, with all the sheikhs and princes agreeing that there would be no Egyptian-style revolution in a kingdom which has a Shia majority of perhaps 70 per cent and a small Sunni minority which includes the royal family.

Protesters in Bahrain retake Pearl Roundabout

CNN reports:

Thousands of joyous Bahrainis retook a major square in the heart of the island nation’s capital Saturday — a dramatic turn of events two days after security forces ousted demonstrators from the spot in a deadly attack.

The sight of citizens streaming into Pearl Roundabout came as the Bahrain royal family appealed for dialogue to end a turbulent week of unrest and the crown prince ordered the removal of the military from the Pearl Roundabout, a top demand by opposition forces.

Nicholas Kristof‘s bundled tweets:

Pearl Roundabout, scene of such tragedy, now is again center of jubilation, cheering and honking. I don’t see any police/ Wow! I’m awed to watch the courage of Bahrainis. Such guts. And it worked: they have reclaimed a place stained with blood/ Delirious joy in #Bahrain “Martyrs’ Roundabout,” as it’s now called. People kissing ground. But the firecrackers make me jump/ Congrats to #Bahrain crown prince, presumably responsible for decision not to shoot protesters today. Hope he prevails/ People Power, 1; King, 0, in #Bahrain. But it’s not over yet. Lots of small children in roundabout. Let’s pray army doesn’t attack/ People still pouring into “Martyrs’ Roundabout” from every direction, say they won’t leave. Mixed views on whether attack will come.

Libyan protesters plead to Obama and the world to take a stand against Qaddafi

Libyan protesters plead to Obama and the world not to be ignored

Libyans are painfully aware of the fact that their country does not attract nearly the same level of interest as Egypt or Iran, except perhaps when it comes to the eccentricities of their notoriously flamboyant dictator. This, despite the fact that the Qaddafi regime has been in power significantly longer than nearly any other autocratic system, during which time it has proved itself among the world’s most brutal and incompetent. Thus, from the moment a group of Libyans inside Libya — taking a cue from their Tunisian and Egyptian neighbors — announced plans for their own day of protest on Feb. 17, Libyan activists outside the country have been working tirelessly to get the word out, circulate audio and video, and pressure media outlets to report on Libya. If the Libyan protesters are ignored, the fear is that Qaddafi — a man who appears to care little what the rest of the world thinks of him — will be able to seal the country off from foreign observers, and ruthlessly crush any uprising before it even has a chance to begin. Eyewitness reports to this effect are already trickling in from Libya, and the death toll appears to be slowly mounting. Regrettably, international attention has thus far been minimal. (Najla Abdurrahman)

Libyan troops attempt to put down unrest in east

Soldiers sought to put down unrest in Libya’s second city on Friday and opposition forces said they were fighting troops for control of a nearby town after crackdowns which Human Rights Watch said killed 24 people.

Protests inspired by the revolts that brought down long-serving rulers of neighboring Egypt and Tunisia have led to violence unprecedented in Muammar Gaddafi’s 41 years as leader of the oil exporting country.

The New York-based rights group Human Rights Watch said that according to its sources inside Libya, security forces had killed at least 24 people over the past two days. Exile groups have given much higher tolls which could not be confirmed. (Reuters)

Libyan opposition groups claim they control several cities

Anti-Gaddafi demonstrators have taken over several cities in eastern Libya but have suffered scores of deaths, according to exiled opposition groups in London.

Government troops have withdrawn from al-Bayda, the scene of earlier confrontations, and protesters have blocked the runway to prevent military reinforcements arriving, the National Front for the Salvation of Libya maintains.

Mohamad Ali Abdalla, the deputy director of the NFSL, said:

I was told that there were 13 deaths in the city of al-Bayda alone last night and six more in Benghazi.

In al-Bayda, the city has been taken over and protesters are dismantling the runway to stop any military planes landing.

In total, there have been 30 deaths in Benghazi since demonstrations began on January 15th. Some of those who died were injured citizens who had been taken to al-Jala hospital in Benghazi.

Members of the revolutionary committee were shooting the injured who were brought in. I was told this by a nurse in al-Jala Hospital.

The government’s revolutionary committee headquarters have been captured in other places, the FNSL claimed. In Ajdabiya, in north-eastern Libya, demonstrations were in charge of the city.

There have been few demonstrations further west nearer to the capital, Tripoli. In the western mountains, nearer to Tunisia, protesters have also been out on the streets.

Several opposition sites have reported that Gaddafi’s regime has been relying on French-speaking soldiers, or “mercenaries” drawn from neighbouring Chad to crack down on the demonstrations. (The Guardian)

Obama stands for democracy — but only after all other alternatives have failed

Yet again, Bahrain’s government has initiated a brutal crackdown on demonstrators — and this time the army is reported to be firing live rounds. A doctor has been killed and paramedics injured while trying to help injured protesters. Ambulances are being denied access to the scene of the massacre.

The BBC reports:

Thousands of people have been voicing anger against Bahrain’s authorities at the funerals of victims of Thursday’s clashes which left four dead.

Crowds attending Friday prayers joined the funeral processions, calling for the overthrow of the ruling family.

At the prayers a Shia cleric described the clashes as a “massacre”, saying the government had shut the door to talks.

The Washington Post reports:

The United States last year provided Bahrain about $20.8 million in military assistance, a substantial amount for such a small country and almost double what it received in 2009. The vast majority of the funds went to pay for improvements to Bahrain’s F-16 fighter fleet and to its navy’s flagship frigate, supplied by the United States in 1996.

In the past, Bahrain has sent more than 100 police to Afghanistan to help build up that country’s force. Overall U.S. counterterrorism aid to Bahrain doubled last year to almost $1.1 million.

Much of that assistance likely went to police and military forces that are suppressing the current protests.

Mark Levine writes:

If the US is Egypt’s primary patron, in Bahrain it is among the ruling family’s biggest tenants, as the country is home to the Fifth Fleet, one of the US military’s most important naval armadas, crucial to protecting Persian Gulf shipping and projecting US power against Iran.

But while Bahrain has long been depicted as relatively moderate compared with its Salafi neighbor, Saudi Arabia, the reality is that the country is repressive and far from free, as citizens have almost no ability to transform their government, which according to the State Department “restricts civil liberties, freedoms of press, speech, assembly, association, and some religious practices.”

In the wake of Egypt, where many people harbor resentment against the Administration for its lack of early support for the democracy movement what can Obama do now? Can he in good conscience acquiesce to the brutal suppression of pro-democracy protesters so soon after his eloquent words and late coming to supporting the Egyptian revolution?

The larger question is: What is more essential to American security today, convenient bases for its ships, planes and troops across the Middle East, or a full transition to democracy throughout the region?

The answer is clearly the latter, as evidenced by the fact that America’s two primary antagonists in the Middle East, al-Qaeda and the Iranian government, have seen their standing sink in proportion to the rise of the pro-democracy movements.

In any war, cold or hot, propaganda is crucial, and here it is impossible to lose sight of the fact that al-Qaeda has had little if anything to say about the Egyptian revolution precisely because it was a massive non-violent jihad that succeeded miraculously where a decade of al-Qaeda blood and vitriol have miserably failed.

As for Iran, the government’s rhetorical support for the Egyptian revolution while it continues to suppress its own democracy movement is clearly emptying the Iranian regime of any remaining credibility as an alternative to the US-dominated order.

In this sense the success-so far-of the Egyptian revolution has presented Obama with a unique window of opportunity to forcefully advocate and press for the same kind of democratic transition across the Middle East and North Africa.

The signs on Tuesday were somewhat optimistic, as the President warned all regional leaders that they should “get ahead of the wave of protest” by moving towards democracy as quickly as possible. Yet Obama refused to mention Bahrain by name in his press conference, even as the government was cracking down on the protesters.

Instead, the US president argued that “each country is different, each country has its own traditions; America can’t dictate how they run their societies,” an utterly meaningless declaration since it contradicts the very advocacy of democracy that the President has made out of the other side of his mouth.

And now, once again, in the wake of government violence against peaceful citizens, the Obama administration stands silent, refusing to openly condemn the Bahraini government. Is the administration incapable of learning from mistakes in the immediate past?

Bahrain crackdown will make citizens more determined

Abdulnabi Alekry writes:

The 14 February marked the 10th anniversary of the National Action Charter, which is considered to be the blueprint of the Bahraini reform project. In 2001, the charter was accepted almost unanimously by eligible voters, with the aim of leading to a constitutional monarchy.

This chapter in Bahrain’s history was supposed to end decades of authoritarian rule, emergency law and repression of political activists. The results are mixed – but the main outcome is superficial democracy. The state wanted to use this year’s anniversary to create a pompous spectacle to legitimise the ruling family. Organised public rallies and parties, as well as glossy newspaper ads and posters, were pervasive.

It is a twist of history that this display of regime power coincided with widespread protests and dramatic changes across the Arab world. In Bahrain, arrests of several hundred political dissidents and human rights activists have been taking place since August 2010. The state used all of its means to portray those that tried to topple the regime as dangerous elements, especially the so-called group of 25 Shia dissidents. It wanted to tell the existing opposition that you are “either with the state or against it”. In addition, the regime successfully foiled the fate of many leftist candidates in the parliamentary elections of October 2010. But to a wide spectrum of Bahraini society these widespread arrests only served as evidence of the authoritarian nature of the state.

So while the local political atmosphere was very tense and there had been many demonstrations in the past, the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt have totally altered the Arab political sphere. Bahraini online activists saw that the time was ripe and emulated the Tunisian and Egyptian example, calling for a “revolution in Bahrain” on 14 February on social networking sites such as Facebook. This day has a symbolic value for Bahrainis as many think they were deceived by the promises of the regime and so the organisers, emboldened by Hosni Mubarak’s downfall, made the most of this moment. While many were sceptical about its success, several thousand demonstrators turned out. The leftwing al-Wa’ad party openly supported the demonstrations and the Shia alliance al-Wifaq endorsed it, but the majority of the demonstrators were young Bahrainis without political affiliations.

Meanwhile, the New York Times reports:

The army took control of this city on Thursday, except at the main hospital, where thousands of people gathered screaming, crying, collapsing in grief, just hours after the police opened fired with birdshot, rubber bullets and tear gas on pro-democracy demonstrators camped in Pearl Square.

As the army asserted control of the streets with tanks and heavily armed soldiers, the once peaceful protesters were transformed into a mob of angry mourners chanting slogans like “death to the king,” while the opposition withdrew from the Parliament and demanded that the government step down.

But for those who were in Pearl Square in the early morning hours, when the police opened fired without warning on thousands who were sleeping there, it was a day of shock and disbelief. Many of the hundreds taken to the hospital were wounded by shotgun blasts, doctors said, their bodies speckled with pellets or bruised by rubber bullets or police clubs.

In the morning, there were three bodies already stretched out on metal tables in the morgue at Salmaniya Medical Complex: Ali Mansour Ahmed Khudair, 53, dead, with 91 pellets pulled from his chest and side; Isa Abd Hassan, 55, dead, his head split in half; Mahmoud Makki Abutaki, 22, dead, 200 pellets of birdshot pulled from his chest and arms.

Doctors said that at least two others had died and that several patients were in critical condition with serious wounds. Muhammad al-Maskati, of the Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights, said that he had received at least 20 calls from frantic parents searching for young children lost in the chaos of the attack.

Gene Sharp’s theories of non-violent revolution

The New York Times profiles Gene Sharp, whose writings on non-violent revolution have inspired dissidents around the world.

Based on studies of revolutionaries like Gandhi, nonviolent uprisings, civil rights struggles, economic boycotts and the like, he has concluded that advancing freedom takes careful strategy and meticulous planning, advice that Ms. Ziada said resonated among youth leaders in Egypt. Peaceful protest is best, he says — not for any moral reason, but because violence provokes autocrats to crack down. “If you fight with violence,” Mr. Sharp said, “you are fighting with your enemy’s best weapon, and you may be a brave but dead hero.”

Autocrats abhor Mr. Sharp. In 2007, President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela denounced him, and officials in Myanmar, according to diplomatic cables obtained by the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks, accused him of being part of a conspiracy to set off demonstrations intended “to bring down the government.” (A year earlier, a cable from the United States Embassy in Damascus noted that Syrian dissidents had trained in nonviolence by reading Mr. Sharp’s writings.)

In 2008, Iran featured Mr. Sharp, along with Senator John McCain of Arizona and the Democratic financier George Soros, in an animated propaganda video that accused Mr. Sharp of being the C.I.A. agent “in charge of America’s infiltration into other countries,” an assertion his fellow scholars find ludicrous.

“He is generally considered the father of the whole field of the study of strategic nonviolent action,” said Stephen Zunes, an expert in that field at the University of San Francisco. “Some of these exaggerated stories of him going around the world and starting revolutions and leading mobs, what a joke. He’s much more into doing the research and the theoretical work than he is in disseminating it.”

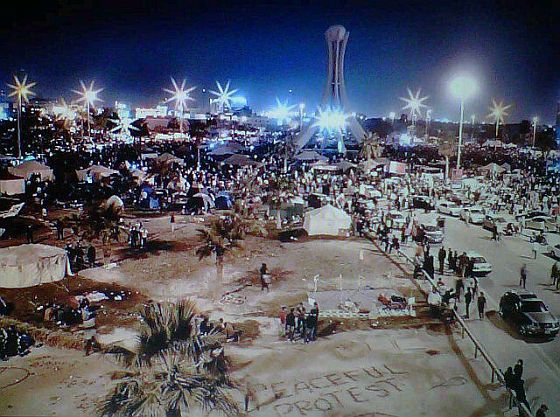

Police in lethal crack down on peaceful mass protest in Bahrain

Peaceful protest at Pearl Roundabout several hours before police launched a deadly assault at 3am Thursday morning.

Al Jazeera is now reporting that at least two people have been killed and dozens injured as Bahrain police attacked sleeping demonstrators in the early hours of Thursday morning. The New York Times said:

Hundreds of riot police surrounded the nation’s symbolic center, Pearl Square, in the early morning Thursday, raining tear gas and percussion grenades on thousands of demonstrators who had poured into the square all day Wednesday to challenge the country’s absolute monarchy.

The protesters, including women and children, had been camping out and the atmosphere had been festive only hours before. But by about 3:30 a.m. Thursday, people were fleeing, screaming “We were sleeping. We were sleeping,” and ambulances, sirens blaring, were trying to make their way through the crowds.

Witnesses, some of them vomiting from the gas, said they had no warning the police were going to crack down on their peaceful protest before rows of police vehicles with blue flashing lights began to circle the area.

Shiite opposition leaders had spent the day Wednesday issuing assurances that they were not being influenced by Iran and were not interested in transforming the monarchy into a religious theocracy like the Islamic republic in Iran.

But that did not stop what appeared to be government attempts to deter the demonstrators who had laid claim to the square, the symbolic heart of the nation. Hours before the police action, the Internet was jammed to a crawl and cellphone service was intermittent. Those efforts, however, only seemed to energize the roaring crowds, which spilled out of the square, tied up roads for as far as the eye could see and united in a celebration of empowerment unparalleled for Bahrain’s Shiites, who make up about 70 percent of the country’s 600,000 citizens.

The following report from Al Jazeera was broadcast before the latest deaths. The position of the Bahrain royal family must now be even more precarious.

Graham Fuller writes:

Where’s the next place to blow in the Arab revolution? Candidates are many, but there’s one whose geopolitical impact vastly exceeds its diminutive size — the island of Bahrain.

This is a place run by an oppressive and corrupt little regime, long coddled by Washington because the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet is headquartered there. The future of the base is far from secure if the regime falls.

A few hard facts about the island that should give pause for thought:

First, Bahrain is a Shiite island. You won’t see it described that way, but it is — 70 percent of the population, more than the percentage of Shiites in Iraq. And like Iraq under Saddam Hussein, these Arab Shiites have been systematically discriminated against, repressed, and denied meaningful roles by a Sunni tribal government determined to maintain its solid grip on the country. The emergence of real democracy, as in Iraq, will push the country over into the Shiite column — sending shivers down the spines of other Gulf rulers, and especially in Riyadh.

Appearances are deceiving. Go to Bahrain and on the surface you won’t feel the same heavy hand that dominates so many other Arab authoritarian states. The island is liberal in its social freedoms. Expats feel at home — you can get a drink, go to nightclubs, go to the beach, party.

But if you look behind the Western and elite-populated high-rises you’ll encounter the Shiite ghettoes — poor and neglected, with high unemployment, walls smeared with anti-regime graffiti.

Free market? Sure, except the regime imports politically neutered laborers from passive, apolitical states that need the money: Filipinos, Bangladeshis, Sri Lankans and other South Asians who won’t make waves or they’re on the next plane out.

The regime also imports its thugs. The ranks of the police are heavily staffed with expat police who often speak no Arabic, have no attachments to the country and who will beat, jail, torture and shoot Bahraini protesters with impunity.

Egypt and the global economic order

Philip Rizk writes:

When an online petition urged Egyptians to protest on January 25, the call was not only taken up by an internet savvy minority. The demonstrators who took to the streets on that day – many of whom remained there until they forced Hosni Mubarak, the country’s autocratic ruler, to step down – transcended the divisions of class, age, religion and political affiliation. The true force behind the Egyptian people’s uprising rested in its leaderless and spontaneous nature. A widely-felt wound had been poked and festering at the centre of that wound was decades of economic exploitation and corruption made tenable by police violence against any form of public dissent.

One sign held up by protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square read: “Tell them to remove the plague and price increases Mubarak.” It was signed: “A citizen that loves Egypt.” That simple message conveyed the essence of the uprising, for the 18 days of protests were, in many ways, the culmination of a wave of much smaller and more localised strikes and demonstrations that had been taking place across the country since 2006.

It all began on December 7, 2006 when workers in the industrial city of El-Mahalla El-Kubra broke the country’s 20-year strike hiatus over the government’s failure to fulfill promises it had made about bonuses. For three days the strikers occupied a factory, calling for the government-backed Labor Federation to be dismantled. The government buckled under the pressure and gave in to the workers’ demands, but the event opened a Pandora’s Box of strikes and protests across the country.

The strikers were responding to the fast-track imposition of neo-liberal economic policies by a cabinet led by Ahmed Nazif, the then prime minister who relentlessly implemented the demands of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). These measures included the privatisation of public factories, the liberalisation of markets, decreasing tariffs and import taxes and the introduction of subsidies for agri-businesses in place of those for small farmers with the aim of increasing agricultural exports.

Such economic policies, which are by no means unique to Egypt, are the fruitful soil of neo-colonialism, whereby multi-national corporations are able to capitalise on economies run by regimes that impose low standards of corporate responsibility towards their labour force, have few environmental protection laws and, in the case of Egypt, subsidise natural resources for big industry. This is coupled with the shrinking of the public sector, which is precisely where most of the labour action in Egypt has been concentrated.

These policies benefitted a small Egyptian elite and foreign corporations, while condemning the country’s working class to a new form of labour-slavery – many public sector employees held up their wage slips during protests, showing meagre monthly earnings of $50 to $90 – and the broader population to the consequences of a shrinking public sector and increased commodity prices.

Samir Amin on the Egyptian challenge to neoliberalism

The Egyptian economist, Samir Amin, President of the World Forum for Alternatives, spoke to World Social Forum TV about the situation in Egypt. The interview was recorded on February 7. A partial transcript of Samir Amin’s remarks can be found here.

Those living under occupation must look to Egypt’s uprising in order to find their own path to freedom

Amjad Atallah writes:

If you live in Washington, DC, the question of what does the Egyptian Revolution mean for Palestine might seem like a strange question. The question du jour here is what does the Egyptian Revolution mean for Israel? The subtext to that second question is what does the Egyptian Revolution mean for Israel’s continued occupation and its denial of equality to non-Jewish citizens and residents. Of course, both questions show an Israel/Palestine-centric view of the world.

Yes, the denial of Palestinian freedom has been an iconic issue of concern not only for Arabs and the larger Muslim world, but also for the Global South and persons of conscience around the world. And once upon a time, the Palestinian struggle for their rights did symbolise the heroism of a people demanding justice for themselves.

But today that mantle lies with the Egyptian and Tunisian peoples. Today, they are the teachers and the rest of us are the pupils. Today, the Arab people of Egypt and Tunisia, and those demonstrating for the same goals throughout the Arab world are providing all of us, including Americans, with hard fought lessons that decades of useless peace-processing and support for authoritarian leaders have let us forget. Here are at least four lessons that have been thrown in our face:

First, the state and the government exist as a consequence of the will of the people, and not vice-versa. It was clear in Hosni Mubarak’s speech yesterday that he has conflated the state of Egypt with himself. His well being is that of Egypt. Attacks on his rule, in his mind, are attacks on Egypt. But Mubarak is not alone in this delusion.

Saddam Hussein saw Iraq in the same way. Listening to the Palestinian rulers in Gaza and Ramallah who administer some of the Palestinian cities under Israeli occupation, you would think that Palestine has become those administrations.

Millions of people marching throughout Egypt today and for the last two weeks have shown us what Egypt actually is – it is the self-determination exercised and demanded by those millions of individuals. Egypt is not an abstract concept tied in to a corrupt rule, it exists because the people today have resurrected themselves and in so doing have resurrected their state.

Palestinians in the first Intifada had tried something very similar but the exercise was ultimately hijacked and ended up in an agreement that actually restricted even further Palestinian space (anyone who lived in the West Bank or Gaza before the Oslo Agreement can tell you it was easier to travel throughout all of historic Palestine before “peace” than after).

This is as democratic as it gets

The tearful TV appearance of Wael Ghonim, the Google executive who had been held in detention blindfolded for 12 days, had an emotional impact that reverberated across Egypt helping bring the revolution to its climax, but as Frederick Bowie notes, no less decisive — even if it garnered much less media attention — was the impact of labor support for the revolution.

Ghonim’s tears certainly played a crucial role in bringing many people, particularly middle-class Egyptians, down into the streets last week. But they cannot directly account for the massive wave of labour unrest which erupted in the days that followed, and which may have played the decisive role in transforming the emotions of the protesters into concrete gains.

Labour activists had proclaimed the creation of an independent trade union federation as early as 30 January, and the city of Suez, one of Egypt’s economic lynchpins, was at the heart of the struggle from day one. (Some believe that when all is finally known, it will be Suez too which has paid the heaviest price for its resistance in terms of dead and injured.) But the initial call for a general strike seemed at first not to find an echo outside one or two areas of the country. And it was not until as late as the middle of last week, when 24,000 workers at the Mahalla Textile Company downed tools, that labour seemed to throw its full weight behind the revolution.

Mahalla has been the epicentre of industrial action in Egypt for much of the last decade, and once the textile workers there had called a strike, it was not long before action spread to encompass armaments factories, public transport networks, universities and hospitals, oil companies, even the actors’ syndicate.

Continuing what has been the hallmark of recent Egyptian labour activism, these actions combined bread-and-butter demands about working conditions and living standards, with attacks on corruption in both management and the official trades unions, and more explicitly political calls for the end of the regime and expressions of solidarity with the protesters in Tahrir Square.

These strikes build on a recent history of labour activism that has grown since the early 2000s to be the most vibrant force for change in Egypt. Driven by the drastic deterioration in the living and working conditions of the majority of the Egyptian people that followed the regime’s compliance with IMF and World Bank demands for the privatization of state-controlled enterprises, the last decade has seen a constantly rising tide of grassroots workplace actions. And as that movement has spread and grown in confidence, its demands have become more and more explicitly political. As Mahalla strike leader Muhammad al-’Attar told a rally in September 2007, “I want the whole government to resign…. I want the Mubarak regime to come to an end. Politics and workers’ rights are inseparable. Work is politics by itself. What we are witnessing here right now, this is as democratic as it gets.”

For Egypt’s workers, the revolution is not just about an image or an emotion. It is about concrete demands, based on their concrete experience of what it is like to go without food, to be unable to pay for their children’s education, and to witness at first hand the corruption that illicitly breeds obscene levels of wealth. And it is rooted in their experience of mounting countless “illegal” actions that have united their communities, built bridges with other forces within Egyptian society, and demonstrated many times over how sheer force of numbers could overwhelm the repressive apparatus of a regime that was looking increasingly neurotic and out-of-touch.

It is too soon to know what exactly tipped the balance at the end of last week, and convinced the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces that the political and institutional superstructure of the Mubarak regime was now a liability, rather than an asset. But it is hard not to subscribe to the implications of one tweet sent by Egyptian microblogger Hossam el-Hamalawy (aka 3arabawy), which seemed to chime immediately with the hopes of many other cyber revolutionaries:

“#EgyWorkers strikes have started. The organized working class is now entering the arena. Mubarak, u r properly fucked.”

The backbone of the Egyptian dictatorship remains in power

General Mohsen el-Fangari appearing on Egyptian TV to confirm the Supreme Military Council will take over running of the country.

Hossam el-Hamalawy writes:

Since Hosni Mubarak fled from Cairo, and even before then, some middle-class activists have been urging Egyptians, in the name of patriotism, to suspend their protests and return to work, singing some of the most ridiculous lullabies: “Let’s build a new Egypt”, “Let’s work harder than ever before”. They clearly do not know that Egyptians are already among the hardest working people in the world.

Those activists want us to trust Mubarak’s generals with the transition to democracy – the same junta that provided the backbone of his dictatorship over the past 30 years. And while I believe the supreme council of the armed forces, which received $1.3bn from the US in 2010, will eventually engineer the transition to a “civilian” government, I have no doubt it will be a government that guarantees the continuation of a system that never touches the army’s privileges, that keeps the armed forces as the institution that has the final say in politics, that guarantees Egypt continues to follow the much hated US foreign policy.

A civilian government should not be made up of cabinet members who have simply removed their military uniforms. A civilian government means one that fully represents the Egyptian people’s demands and desires without any intervention from the top brass. I think it will be very hard to accomplish this, if the junta allows it at all. The military has been the ruling institution in this country since 1952. Its leaders are part of the establishment. And while the young officers and soldiers are our allies, we cannot for one second lend our trust and confidence to the generals.

Robert Fisk writes:

[A] clear divergence is emerging between the demands of the young men and women who brought down the Mubarak regime and the concessions – if that is what they are – that the army appears willing to grant them. A small rally at the side of Tahrir Square yesterday held up a series of demands which included the suspension of Mubarak’s old emergency law and freedom for political prisoners. The army has promised to drop the emergency legislation “at the right opportunity”, but as long as it remains in force, it gives the military as much power to ban all protests and demonstrations as Mubarak possessed; which is one reason why those little battles broke out between the army and the people in the square yesterday.

As for the freeing of political prisoners, the military has remained suspiciously silent. Is this because there are prisoners who know too much about the army’s involvement in the previous regime? Or because escaped and newly liberated prisoners are returning to Cairo and Alexandria from desert camps with terrible stories of torture and executions by – so they say – military personnel. An Egyptian army officer known to ‘The Independent’ insisted yesterday that the desert prisons were run by military intelligence units who worked for the interior ministry – not for the ministry of defence.

As for the top echelons of the state security police who ordered their men – and their faithful ‘baltagi’ plain-clothes thugs — to attack peaceful demonstrators during the first week of the revolution, they appear to have taken the usual flight to freedom in the Arab Gulf. According to an officer in the Cairo police criminal investigation department whom I spoke to yesterday, all the officers responsible for the violence which left well over 300 Egyptians dead have fled Egypt with their families for the emirate of Abu Dhabi. The criminals who were paid by the cops to beat the protesters have gone to ground – who knows when their services might next be required? – while the middle-ranking police officers wait for justice to take its course against them. If indeed it does.

In mid-December, Sarah A. Topol described the extent to which the military controls Egypt’s economy.

The Egyptian military manufactures everything from bottled water, olive oil, pipes, electric cables, and heaters to roads through different military-controlled enterprises. It runs hotels and construction companies and owns large plots of land.

The Egyptian military has “an enormous vested interest in the way things run in Egypt, and you could, I think, be sure that they’ll try to protect those interests,” a Western diplomat in Cairo told me. “There’s a certain conventional wisdom [that] therefore the next president has to come from the military. I don’t know that that’s true. It’s the interest that they’ll be interested in protecting.”

But reporting on the military is difficult. No one wants to talk about the subject, and people who are willing to talk don’t want their names used. If civilians are worried, Egyptian journalists are petrified. “There is Law 313, [passed in] the year 1956, and it bans you from writing about the army,” Hesham Kassem, an independent publisher, told me. “It’s the taboo of journalism.”

McClatchy reports:

Three days after Hosni Mubarak’s resignation, Egypt’s political opposition was bitterly divided over its next moves as the army expanded its near-total control over the country with no overt signs that it’s included anti-government protesters in its decision-making.

A major meeting of opposition leaders and protesters on Monday quickly devolved into arguments and diatribes, underscoring how difficult it will be for the diverse, leaderless revolutionary movement to coalesce around a political platform before elections that Egypt’s military caretakers have pledged to hold.

While one set of opposition figures battled itself, a group of seven young, middle-class democracy activists said that they’d met with senior members of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The protesters said the generals voiced their “sincere intention to preserve the gains of the revolution.”

But the army, which Friday took power from Mubarak and since has issued only brief statements of its plans for the transition to a democratically elected government, made no mention of the meeting in its only statement of the day — a call for an end to growing labor protests.

The army has met some of the key demands of the protesters who ousted Mubarak. It’s dissolved his rubber-stamp parliament and suspended the flawed constitution. Many Egyptians consider the military the country’s most credible public institution after it remained neutral during the 18-day popular uprising and refused to fire on protesters.

But the military leadership — which includes former members of the Mubarak regime and is headed by his defense minister, Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi — so far has emphasized stability over transparency.

The democratic threat to the Jewish state

Ilan Pappe writes on why Israelis fear the prospect of becoming surrounded democratic Arab states.

Nonviolent, democratic (be they religious or not) Arabs are bad for Israel. But maybe these Arabs were there all along, not only in Egypt, but also in Palestine. The insistence of Israeli commentators that the most important issue at stake — the Israeli peace treaty with Egypt — is a diversion, and has very little relevance to the powerful impulse that is shaking the Arab world as a whole.

The peace treaties with Israel are the symptoms of moral corruption not the disease itself — this is why Syrian President Bashar Asad, undoubtedly an anti-Israeli leader, is not immune from this wave of change. No, what is at stake here is the pretense that Israel is a stable, civilized, western island in a rough sea of Islamic barbarism and Arab fanaticism. The “danger” for Israel is that the cartography would be the same but the geography would change. It would still be an island but of barbarism and fanaticism in a sea of newly formed egalitarian and democratic states.

In the eyes of large sections of Western civil society the democratic image of Israel has long ago vanished; but it may now be dimmed and tarnished in the eyes of others who are in power and politics. How important is the old, positive image of Israel for maintaining its special relationship with the United States? Only time will tell.

But one way or another the cry rising from Cairo’s Tahrir Square is a warning that fake mythologies of the “only democracy in the Middle East,” hardcore Christian fundamentalism (far more sinister and corrupt than that of the Muslim Brotherhood), cynical military-industrial corporate profiteering, neo-conservatism and brutal lobbying will not guarantee the sustainability of the special relationship between Israel and the United States forever.