The New York Times reports: Late on a moonless night last March, a plane smuggling nearly half a ton of cocaine touched down at a remote airstrip in Honduras. A heavily armed ground crew was waiting for it — as were Honduran security forces. After a 20-minute firefight, a Honduran officer was wounded and two drug traffickers lay dead.

Several news outlets briefly reported the episode, mentioning that a Honduran official said the United States Drug Enforcement Administration had provided support. But none of the reports included a striking detail: that support consisted of an elite detachment of military-trained D.E.A. special agents who joined in the shootout, according to a person familiar with the episode.

The D.E.A. now has five commando-style squads it has been quietly deploying for the past several years to Western Hemisphere nations — including Haiti, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala and Belize — that are battling drug cartels, according to documents and interviews with law enforcement officials.

The program — called FAST, for Foreign-deployed Advisory Support Team — was created during the George W. Bush administration to investigate Taliban-linked drug traffickers in Afghanistan. Beginning in 2008 and continuing under President Obama, it has expanded far beyond the war zone.

“You have got to have special skills and equipment to be able to operate effectively and safely in environments like this,” said Michael A. Braun, a former head of operations for the drug agency who helped design the program. “The D.E.A. is working shoulder-to-shoulder in harm’s way with host-nation counterparts.”

The evolution of the program into a global enforcement arm reflects the United States’ growing reach in combating drug cartels and how policy makers increasingly are blurring the line between law enforcement and military activities, fusing elements of the “war on drugs” with the “war on terrorism.”

Category Archives: law

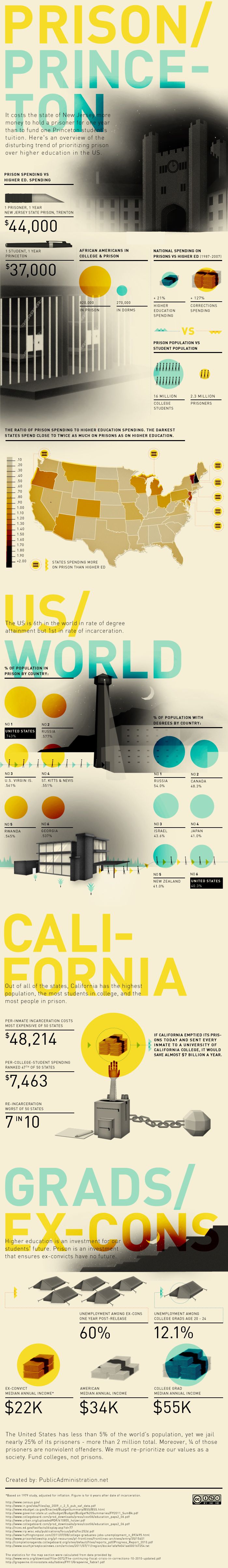

Why does the U.S. spend more on prisons than higher education?

If California emptied its prisons today and sent every inmate to a University of California college it would save $7 billion a year!

That’s one of the stunning statistics presented in the chart below, created by Joseph Staten, an info-graphic researcher with Public Administration (h/t Brian Resnick at the Atlantic.)

In the land of the free, we should be asking why the government invests more in locking up it citizens than in equipping them with the skills to make the most of their liberty and why the country that is only the sixth largest in the world is #1 in the rate of incarceration.

Glenn Greenwald on two-tiered U.S. justice system, Obama’s assassination program & the Arab Spring

Palestinians could pursue war crimes charges without full statehood: ICC prosecutor

The Toronto Star reports:

In the fierce debate over the Palestinian bid for UN membership, one unseen presence has cast a long shadow.

It’s that of Luis Moreno-Ocampo, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court — the body Israel has long feared would take up Palestinian allegations of war crimes if its statehood bid is successful.

A few blocks away from the UN this week, the man at the centre of the controversy said if Palestine becomes a member state, or a lower-ranked non-member observer state, it could be eligible to pursue claims against Israel.

“If the General Assembly says they are an observer state, in accordance with the all-state formula, this should allow them . . . to be part of the International Criminal Court,” he told the Star.

How American police get away with crime against the people they are sworn to protect

Crime and punishment

Norway's prison guards undergo two years of training at an officers' academy and enjoy an elevated status compared with their peers in the U.S. and Britain. Their official job description says they must motivate the inmate 'so that his sentence is as meaningful, enlightening and rehabilitating as possible,' so they frequently eat meals and play sports with prisoners. At Halden high-security prison, half of all guards are female, which its governor believes reduces tension and encourages good behavior. -- Time Magazine

Reading Anders Behring Breivik’s account of his preparations for his July 22 attacks in Oslo and Utøya evokes a certain dread at the sight of such a deliberate effort to cause carnage. Breivik expresses no doubt about what he is doing other than the fear that he might run out of funds and be unable to rent the car in which he intends to load explosives.

Mass murder, committed with such cold calculation surely merits the harshest punishment. Many Americans are thus now perplexed to learn about the apparent leniency of Norway’s penal system. Eli Lake’s views, as expressed in conversation with Hans-Inge Lango, will be shared by many.

But if Norway’s approach to crime is really sending the wrong message, just look at the numbers: an incarceration rate of 71 per 100,000 Norwegians versus 743 per 100,000 Americans; and while in Norway 80% of prisoners once released never return to jail, in the US almost 70% end up back behind bars.

Americans should not be asking whether Norway is capable of being tough enough with terrorists, but instead why a country that spends more on its security than any other also imprisons more of its own citizens than any other. (And for any of the xenophobes out there who might want to attribute America’s high incarceration rate to the high number of immigrants in this country, Germany has a similar proportion of immigrants and an incarceration rate of 85 per 100,000.)

Holder defends terror trials in civilian courts

The Associated Press reports:

Attorney General Eric Holder on Thursday defended the prosecution of terrorism suspects in civilian court after the top-ranking Senate Republican urged him to send two Iraqis to Guantanamo Bay rather than try them in Kentucky.

Holder criticized what he called a “rigid ideology” among political opponents working to prevent terror trials that have been successfully handled by civilian courts hundreds of times.

“Politics has no place — no place — in the impartial and effective administration of justice,” Holder said in remarks prepared for delivery to the American Constitution Society’s convention. “Decisions about how, where, and when to prosecute must be made by prosecutors, not politicians.”

Although Holder didn’t mention Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell by name, his comments come two days after McConnell took to the Senate floor and urged Holder’s Justice Department to send terrorism suspects Waad Ramadan Alwan and Mohanad Shareef Hammadi to Navy-run prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He said a trial planned in his home state of Kentucky could risk retaliatory attacks against judges, jurors and the broader community.

The Justice Department says there have been more than 400 convictions of terrorism-related charges in civilian courts.

“Not one of these individuals has escaped custody,” Holder said. “Not one of the judicial districts involved has suffered retaliatory attacks. And not one of these terrorists arrested on American soil has been tried by a military commission.”

The quaint and obsolete Nuremberg principles

Glenn Greenwald writes:

Benjamin Ferencz is a 92-year-old naturalized U.S. citizen, American combat soldier during World War II, and a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, where he prosecuted numerous Nazi war criminals, including some responsible for the deaths of upward of 100,000 innocent people. He gave a fascinating (and shockingly articulate) 13-minute interview yesterday to the CBC in Canada about the bin Laden killing, the Nuremberg principles, and the U.S. role in the world. Without endorsing everything he said, I hope as many people as possible will listen to it.

All of Ferencz’s answers are thought-provoking — including his discussion of how the Nuremberg Principles apply to bin Laden — but there’s one answer he gave which I particularly want to highlight; it was in response to this question: “so what should we have learned from Nuremberg that we still haven’t learned”? His answer:

I’m afraid most of the lessons of Nuremberg have passed, unfortunately. The world has accepted them, but the U.S. seems reluctant to do so. The principal lesson we learned from Nuremberg is that a war of aggression — that means, a war in violation of international law, in violation of the UN charter, and not in self-defense — is the supreme international crime, because all the other crimes happen in war. And every leader who is responsible for planning and perpetrating that crime should be held to account in a court of law, and the law applies equally to everyone.

These lessons were hailed throughout the world — I hailed them, I was involved in them — and it saddens me to no end when Americans are asked: why don’t you support the Nuremberg principles on aggression? And the response is: Nuremberg? That was then, this is now. Forget it.

To be candid, I’ve been tempted several times to simply stop writing about the bin Laden killing, because passions are so intense and viewpoints so entrenched, more so than any other issue I’ve written about. There’s a strong desire to believe that the U.S. — for the first time in a long time — did something unquestionably noble and just, and anything which even calls that narrative into question provokes little more than hostility and resentment. Nonetheless, the bin Laden killing is going to shape how many people view many issues for quite some time, and there are still some issues very worth examining.

One bothersome aspect about the reaction to this event is the notion that bin Laden is some sort of singular evil, someone so beyond the pale of what is acceptable that no decent person would question what happened here: he killed civilians on American soil and the normal debates just don’t apply to him. Thus, anyone who even questions whether this was the right thing to do, as President Obama put it, “needs to have their head examined” (presumably that includes Benjamin Ferencz). In other words, so uniquely evil is bin Laden that unquestioningly affirming the rightness of this action is not just a matter of politics and morality but mental health. Thus, despite the lingering questions about what happened, it’s time, announced John Kerry, to “shut up and move on.” I know Kerry is speaking for a lot of people: let’s all agree this was Good and stop examining it. Tempting as that might be — and it is absolutely far easier to adhere to that demand than defy it — there is real harm from leaving some of these questions unexamined.

The Obama administration’s appalling decision to give Khalid Sheikh Mohammed a military trial

Dahlia Lithwick writes:

Today, by ordering a military trial at Guantanamo for 9/11 plotter Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his co-defendants, Attorney General Eric Holder finally put the Obama administration’s stamp on the proposition that some criminals are “too dangerous to have fair trials.”

In reversing one of its last principled positions—that American courts are sufficiently nimble, fair, and transparent to try Mohammed and his confederates—the administration surrendered to the bullying, fear-mongering, and demagoguery of those seeking to create two separate kinds of American law. This isn’t just about the administration allowing itself to be bullied out of its commitment to the rule of law. It’s about the president and his Justice Department conceding that the system of justice in the United States will have multiple tiers—first-class law for some and junk law for others.

Every argument advanced to scuttle the Manhattan trial for KSM was false or feeble: Open trials are too dangerous; major trials are too expensive; too many secrets will be spilled; public trials will radicalize the enemy; the public doesn’t want it.

Of course, exactly the same unpersuasive claims could have been made about every major criminal trial in Western history, from the first World Trade Center prosecution to the Rosenberg trial to the Scopes Monkey trial to Nuremburg. Each of those trials could have been moved to some dark cave for everyone’s comfort and well-being. Each of those defendants could have been tried using some handy choose-your-own-ending legal system to ensure a conviction. But the principle that you don’t tailor justice to the accused won out, and, time after time, the world benefited.

Now the Obama administration—having loudly and proudly made every possible argument against a two-tier justice system—is capitulating to it.

But make no mistake about it: It won’t stop here. Putting the administration’s imprimatur on the idea that some defendants are more worthy of real justice than others legitimates the whole creeping, toxic American system of providing one class of legal protections for some but not others: special laws for children of immigrants, special laws for people who might look like immigrants, different jails for those who seem too dangerous, special laws for people worthy of wiretapping, and special laws for corporations. After today it will be easier than ever to use words and slogans to invent classes of people who are too scary to try in regular proceedings.

Say what you want about how Congress forced Obama’s hand today by making it all but impossible to try the 9/11 conspirators in regular Article II courts. The only lesson learned is that Obama’s hand can be forced. That there is no principle he can’t be bullied into abandoning. In the future, when seeking to pass laws that treat different people differently for purely political reasons, Congress need only fear-monger and fabricate to get the president to cave. Nobody claims that this was a legal decision. It was a political triumph or loss, depending on your viewpoint. The rule of law is an afterthought, either way.

A legacy Obama should avoid: Allowing detentions without trials

Tom Malinowski from Human Rights Watch writes:

It is an iron law of American government that institutions created to meet a temporary contingency are almost impossible to dismantle once the contingency has passed. If not for the Soviet threat, for example, the United States hardly would have established multiple intelligence agencies, military bases in Germany or a massive nuclear weapons complex. Yet 20 years after the Berlin Wall fell, these elements of the Cold War national security state are still with us.

The institutions cobbled together after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks may be just as resistant to change, as President Obama is finding in his struggle to close the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay.

In 2008, presidential candidates Obama and John McCain promised to close Guantanamo. (McCain said he would move all the prisoners to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., on his first day in office.) But last year, Robert Gates’s Pentagon fought to preserve the facility’s military commissions. Then, Congress restricted transfers of prisoners to the United States for detention or trial. Last week, White House press secretary Robert Gibbs said that closing Guantanamo would “depend on the Republicans’ willingness to work with the administration,” which, if true, is a nice way of saying “never.”

Now Obama is reportedly weighing an executive order to clarify the rules for detaining some four dozen Guantanamo prisoners whom his administration deems too dangerous to release but who cannot be tried. These men pose a unique problem left over from the Bush administration, when evidence was poorly maintained, some detainees were tortured and others radicalized by their years in prison. If Obama’s order gives them better process, it will be a step forward.

Some, however, are urging Obama to take a more fateful step: to issue an order covering not just the hard cases he inherited in Guantanamo but also allowing detention without trial of any terrorism suspect who may be apprehended in the future, even if far from a battlefield. Such an order could transform the Guantanamo system from an unfortunate, improvised response to Sept. 11 into a permanent feature of our legal landscape.

Don’t deny detainees their day in court

Amos N. Guiora and Laurie R. Blank write:

The idea that every person deserves his or her “day in court” is a fundamental principle in the United States and many countries worldwide. Yet more than nine years after 9/11, the United States remains paralyzed not just about how to give the thousands of detainees in U.S. custody around the world their day in court but about whether to give them that day in court.

Multiple judicial forums have been created to try nonstate actors who have perpetrated war crimes from Rwanda to Sierra Leone to Cambodia to the former Yugoslavia — to give them their day in court. That makes the failure to answer this question for post-9/11 detainees particularly perplexing and deeply troubling.

Two successive administrations have been incapable of answering what should be the most basic questions: if, how and where to try terrorists. In the meantime, post-9/11 detainees languish in indefinite detention. The result is a fundamental and overwhelming violation of the rights of individuals who are no more than suspects, in either past or (more problematic) future acts.

The Obama administration now intends to issue an executive order establishing indefinite detention without trial for detainees at Guantanamo Bay. This decision will formalize this violation of basic rights. Denying individual accountability will now be official U.S. policy and law.

WikiLeaks v the imperial presidency’s poodle

Pratap Chatterjee writes:

Anticipating Sunday’s release of classified US embassy cables, Harold Koh, the top lawyer to the US state department, fired off a letter to Julian Assange, the editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks, on Saturday morning accusing him of having “endangered the lives of countless individuals”. Thus Koh pre-emptively made himself the figurehead for the US government’s reaction to the WikiLeaks release; the White House’s subsequent statement has echoed his attack.

Koh, a former dean of Yale law school, is also the man who authored a legal opinion for the Obama administration this past March stating that the president had the right to authorise “lethal operations” to target and kill alleged terrorists anywhere in the world without judicial review. This is in spite of the fact that other respected law professors and human rights organisations from Amnesty to Human Rights Watch have expressed grave worries that such actions also endanger the lives of countless individuals.

Koh – and another famous White House legal adviser named John Yoo – were both once fierce critics of what they believed were executive abuses by the president of US interests and standards of conduct overseas. Yet, once they themselves ascended to become acolytes of the highest office in the land, they both came to believe that the president alone had the right to determine what was right and what was wrong.

The rock upon which our nation no longer rests

In a landmark case, the first trial of a former Guantánamo detainee, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan of United States District Court in Manhattan made a ruling that presents a major setback for the Department of Justice. He barred the key witness from testifying because he had been identified and located through torturing the accused, Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, who was being held in a secret prison by the CIA.

In a landmark case, the first trial of a former Guantánamo detainee, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan of United States District Court in Manhattan made a ruling that presents a major setback for the Department of Justice. He barred the key witness from testifying because he had been identified and located through torturing the accused, Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, who was being held in a secret prison by the CIA.

Kaplan explained his decision in this way:

The Court has not reached this conclusion lightly. It is acutely aware of the perilous nature of the world in which we live. But the Constitution is the rock upon which our nation rests. We must follow it not only when it is convenient, but when fear and danger beckon in a different direction. To do less would diminish us and undermine the foundation upon which we stand.

At face value, this sounds like one of those rare feel-good moments in the post 9/11 era when someone who has sworn to uphold the Constitution took that responsibility very seriously.

“… the Constitution is the rock upon which our nation rests.” I imagine Judge Kaplan took satisfaction in crafting that sentence. It’s good.

But just in case anyone might be alarmed that the innocent-until-proven-guilty Ghailani might end up being acquited, the judge was eager to pacify such fears.

[H]is status as an “enemy combatant” probably would permit his detention as something akin to a prisoner of war until hostilities between the United States and Al Qaeda and the Taliban end even if he were found not guilty in this case.

So is Ghailani on trial to determine his innocence or guilt, or simply to decide on the location of his prison cell?

Isn’t that the direction in which fear and danger beckon?

The Siddiqui sentence: 86 years for pointing a weapon

The details of a bizarre incident at an Afghan National Police facility in Ghazni, eastern Afghanistan, on July 18, 2008, are still in dispute. Even so, the woman at the center of the story will probably spend the rest of her life in jail.

Without any evidence being produced that she had fired a shot from a gun she reportedly grabbed while being held under arrest, Dr Aafia Siddiqui, an MIT-educated Pakistani neuroscientist, was convicted of attempted murder in February. On Thursday, District Court Judge Richard Berman sentenced the 38-year-old to 86 years in prison. In response, protesters took to the streets in Pakistan.

The jury found that Siddiqui acted without premeditation. But in a four-hour sentencing hearing, Judge Richard Berman repeatedly termed her acts premeditated. Her defense lawyers argued for a minimum sentence of 12 years, saying that Siddiqui is severely mentally ill.

Needless to say, the case now goes to appeal.

Defense attorney Charles Swift said that government authorities never made available the U.S. military reports on the incident. He said the report, which was declassified by the government after it was published this year on the WikiLeaks website, does not mention Siddiqui as having fired the gun. It said only that she pointed a weapon. He said he believes there was a further in-depth investigation of the incident by the military that has also been withheld from the defense.

“I think there’s real concern over the government’s obligation to turn over exculpatory evidence,” he told reporters. “And I don’t blame the prosecution in this case. What I’ve found in national security cases like this is they have as big a battle trying to get evidence as anyone does. But the United States, to do justice, has to do it credibly and has to produce all the documents. And that’s one of three or four huge ongoing appellate issues.”

If Charles Swift sounds like a familiar name it’s because he has the rare distinction of having stood up and successfully defended his country while its Constitution faced attack from the Bush administration. In Hamdan vs Rumsfeld, Swift won a major victory for the rule of law.

The case of Dr Siddiqui exposes a moral fallacy that has haunted America throughout the war on terrorism. It is this: that injustice is something that can only be done to the innocent.

We have abandoned what used to be the universally recognized foundation of a just legal system: that it treats the guilty and the innocent with fairness and impartiality.

—

(For fascinating background on the Siddiqui case, read Declan Walsh’s November 2009 report in The Guardian.)

Can Americans be murdered by the Israeli government with impunity?

For several days, Israel has been able to contain some of the fallout from the flotilla massacre by withholding information about the dead and injured. The object of this exercise has clearly been to slow the flow of information in the hope that by the time the most damning facts become known, the international media’s attention will have turned elsewhere.

But the dead now have names and faces and one turns out to be a nineteen-year-old American: Furkan Dogan.

Dogan is alleged to have been shot with five bullets, four in the head.

Does the Obama administration intend to investigate the circumstances in which one of its citizens was killed? Protecting the lives of Americans is after all the most fundamental responsibility of our government.

Dogan’s death was presumably instant, but according to Al Jazeera‘s Jamal Elshayyal there were others on board the Mavi Marmara who died because Israeli soldiers refused to treat their injuries.

“After the shooting and the first deaths, people put up white flags and signs in English and Hebrew. An Isreali [on the ship] asked the soldiers to take away the injured, but they did not and the injured died on the ship.”

Crimes have been committed and since the suspects all acted under the direction of the Israeli government and its defense forces and took place on international waters outside Israel’s area of legal jurisdiction, “a prompt, impartial, credible and transparent investigation conforming to international standards” — a demand made by the UN Security Council with the support of the Obama administration — cannot be conducted by the Israeli government or a commission appointed by them. An investigation conforming to international standards must also be an international inquiry.

Israel’s security cannot come at any price

Ben Saul, who teaches the law of armed conflict at The University of Sydney, writes:

Israel’s response to the Gaza flotilla is another unfortunate example of Israel clothing its conduct in the language of international law while flouting it in practice. If you believe Israeli government spokesmen, Israel is metabolically incapable of violating international law, placing it alongside Saddam Hussein’s Information Minister in self-awareness.

Israel claims that paragraph 67(a) of the San Remo Manual on Armed Conflicts at Sea justified the Israeli operation against the flotilla. (The San Remo Manual is an authoritative statement of international law applicable to armed conflicts at sea.)

Paragraph 67(a) only permits attacks on the merchant vessels of neutral countries where they “are believed on reasonable grounds to be carrying contraband or breaching a blockade, and after prior warning they intentionally and clearly refuse to stop, or intentionally and clearly resist visit, search or capture”.

Israel argues that it gave due warnings, which were not heeded.

What Israel conveniently omits to mention is that the San Remo Manual also contains rules governing the lawfulness of the blockade itself, and there can be no authority under international law to enforce a blockade which is unlawful. Paragraph 102 of the Manual prohibits a blockade if “the damage to the civilian population is, or may be expected to be, excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated from the blockade”.

Lies and cover-ups in the name of force protection

When a leaked US Army report recently revealed that the military regards Wikileaks as a potential force protection threat, the leak not only exposed the army’s fears but it also shed light on the breadth of this concept: force protection. From the Pentagon’s perspective, protecting American troops and making sure they stay out of harm’s way includes shielding them from unwelcome media attention and perhaps even concealing evidence of crimes.

Dan Froomkin reports on the latest example of a story the Pentagon has worked hard to supress:

Calling it a case of “collateral murder,” the WikiLeaks Web site today released harrowing until-now secret video of a U.S. Army Apache helicopter in Baghdad in 2007 repeatedly opening fire on a group of men that included a Reuters photographer and his driver — and then on a van that stopped to rescue one of the wounded men.

None of the members of the group were taking hostile action, contrary to the Pentagon’s initial cover story; they were milling about on a street corner. One man was evidently carrying a gun, though that was and is hardly an uncommon occurrence in Baghdad.

Reporters working for WikiLeaks determined that the driver of the van was a good Samaritan on his way to take his small children to a tutoring session. He was killed and his two children were badly injured.

In the video, which Reuters has been asking to see since 2007, crew members can be heard celebrating their kills.

“Oh yeah, look at those dead bastards,” says one crewman after multiple rounds of 30mm cannon fire left nearly a dozen bodies littering the street.

A crewman begs for permission to open fire on the van and its occupants, even though it has done nothing but stop to help the wounded: “Come on, let us shoot!”

The president’s conscience, on hold

The White House counsel ideally serves as the president’s conscience.

But late last year, Barack Obama’s conscience was surgically removed.

Greg Craig, as Obama’s top lawyer, was the point man on a number of hot-button issues, the fieriest being how to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay. Craig argued for holding fast to the principles that Obama outlined before he became president, regardless of the immediate political consequences — an idealistic approach that, in a White House filled with increasingly pusillanimous pragmatists, earned him some powerful enemies.

After a steady drip of leaks over a period of months to the Washington Post, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and other news outlets to the effect that his days were numbered, Craig finally resigned in November.

He was replaced by Robert Bauer, a politically adept consummate Washington insider whose expertise is in campaign finance law — in short, a man whose job is to win elections, not defend principles.

At the same time, Attorney General Eric Holder has been increasingly marginalized and cut out of the White House decision-making loop. So now the coast is clear for the White House to make important legal and national security calls on purely political grounds.

The only question that remains is whether Obama himself will have any last-minute qualms about turning his back on his own principles.