McChrystal’s stovepipe operation

By Mark Perry, Asia Times, December 10, 2009

President Barack Obama’s national address last Tuesday not only detailed the United States’ strategy on Afghanistan, it laid bare his new administration’s strengths and weaknesses – and confirmed the growing suspicion that, eight years after September 11, 2001, meeting America’s global challenges with a military response remains the default position of the Washington policymaking establishment.

“Don’t underestimate the impact that eight years of the [George W] Bush administration has had in Washington,” a senior State Department official explained this last summer. “The Bush people set out the language of the war on terrorism, invented the vocabulary, defined the terms. People talk about the importance of ‘doing’ diplomacy, but no one really knows what that means or how tough it can really be.”

At least initially, this assessment seemed contradicted by the administration’s flurry of diplomatic activity. Its first months were taken up by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s globetrotting, special envoy George Mitchell’s high-profile Jerusalem meetings, AfPak specialist Richard Holbrooke’s repeated initiatives with Pakistan’s President Asif Ali Zardari – and Obama’s decision to engage Iran in direct talks about its nuclear program.

Suddenly, surprisingly, the military seemed relegated to playing a minor role in Washington: Bush’s hero David Petraeus, the US commander for the greater Middle East, was no longer in the headlines, the war in Iraq seemed well in hand and Defense Secretary Robert Gates was nowhere to be seen.

All of this changed in May, when a series of well-timed Taliban offensives led to a spike in US casualties and Gates decided to replace the US Afghan commander, David McKiernan, with Lieutenant General Stanley McChrystal. The change did not come as a surprise to Pentagon officers, who had watched Petraeus and McKiernan struggle through a difficult relationship: “The two couldn’t be in the same room together,” a McKiernan aide says. “We knew there’d be a fist fight if we left them alone.” The disagreement was personal: McKiernan resented answering to an officer whom he had once commanded and viewed as politically ambitious.

But the relationship was also scarred by a subtle disagreement over how to meet the Taliban challenge. Both McKiernan and Petraeus agreed that the Taliban posed a security challenge to the Afghan government, but McKiernan focused first on development – on building what he called “human capital”. Petraeus disagreed: you can’t build “human capital” without security, he argued, and the security situation in the country was deteriorating. Then too, Petraeus thought, what was needed in Afghanistan was an officer who could respond creatively to what Petraeus believed was turning into an asymmetric fight – and McKiernan was an officer with a deep background in running conventional wars.

McChrystal, a former Green Beret and a celebrated special operations commander, was the answer. Petraeus recommended a change to Gates, and Gates agreed. Within days of his May 11 appointment, McChrystal showed up in the Afghan capital, Kabul, with a team of counter-insurgency experts who commandeered McKiernan’s headquarters and fanned out throughout the country.

McChrystal’s teams were told to identify the problem and find a solution. “They absolutely flooded the zone,” a US development officer says. “There must have been hundreds of them. They were in every province, every village, talking to everyone. There were 10 of them for every one of us.” Not surprisingly, within weeks of their deployment, McChrystal’s team leaders had concluded that the US was facing was an escalating insurgency that could only be checked with an increase in US troops. In-country State Department officials rolled their eyes: “What a shock. If you deploy a gang squad, they’re going to find a gang,” a senior State Department official says with a tinge of bitterness. “They were looking for an insurgency and they found one.”

“From the minute that McChrystal showed up in Kabul, he drove the debate,” a White House official confirms. “You’ll notice – from May on it was no longer a question of whether we should follow a military strategy or deploy additional troops. It was always, ‘should we do 20,000 or 30,000 or 40,000, or even 80,000’? We weren’t searching for the right strategy; we were searching for the right number.”

A senior State Department official, watching McChrystal from her State Department perch in Washington, remembers the frustration among the department’s top policymakers: “We kept saying ‘we need to open up to the other side, like we did in Iraq with the Anbar insurgency,’ and the military kept saying, ‘well this isn’t Iraq.’ And so we’d answer: ‘fine, so if Afghanistan isn’t Iraq, then why do you keep talking about a surge?’ And we never got an answer.”

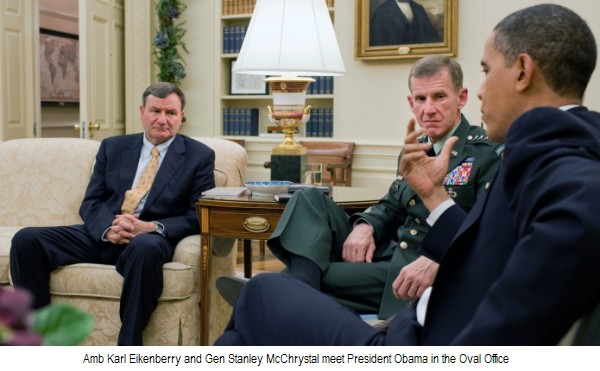

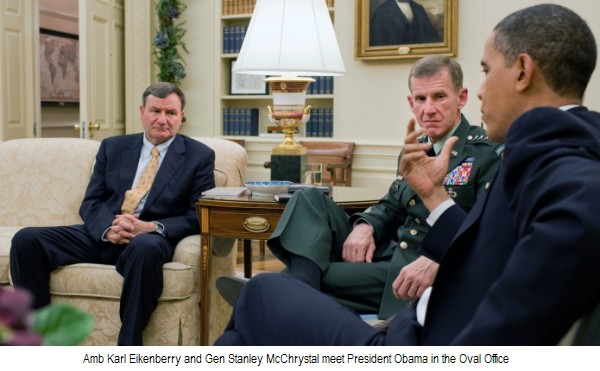

The State Department’s frustration extended into the embassy in Kabul, where the US ambassador, Karl Eikenberry, was having his own problems with McChrystal. The appointment of Eikenberry in March of 2009 had been greeted with skepticism in the State Department because of his background as a West Pointer, a retired lieutenant general and a US security coordinator in the country. But if anyone would be sympathetic to McChrystal, it was now thought, it would be Eikenberry.

But that’s not what happened: Eikenberry won friends among professional diplomats for his easygoing manner and quick understanding of their problems – and for his open irritation at McChrystal’s imperious manner. “McChrystal came in and he just thought he was some kind of Roman proconsul, a [Douglas] MacArthur,” an Eikenberry colleague notes. “He was going to run the whole thing. He didn’t need to consult with the State Department or civilians, let alone the ambassador. This was not only the military’s show, it was his show.”

But McChrystal was not only able to “flood the zone” in Afghanistan, he was able to do so in Washington. As the director of the Joint Staff, a position he held just prior to arriving in Kabul, McChrystal established the Pakistan-Afghanistan Coordinating Cell (PACC), a 70-person military-civilian operations group housed in the Pentagon’s National Command Center, one of the most secure offices in the world. “This isn’t a place you just wander in and out of,” a senior Pentagon official says. The “PACC” bypassed the normal command structure – and the State Department. It reported to McChrystal, who rotated its officers in and out of Kabul every three to four months.

The PACC is “a stovepipe operation”, this senior Pentagon official notes. “It’s beautiful. It’s headed up by McChrystal acolytes, former special operations officers who view him [McChrystal] as their patron. So they follow his lead. And there is no requirement for them to share any of the information they get from Kabul with the State Department or anyone else – let alone with Eikenberry. This is McChrystal’s game. The PACC people in Washington pass information to McChrystal without going through any channels and they take the best information from Kabul and they brief [JCS chairman Admiral Mike] Mullen – and he briefs the president. So during the run-up to the Afghanistan decision, the military always looked current. They had the best information. Everyone else looked like a bunch of amateurs. Eikenberry was out of the loop. He had no chop [influence] on any of it. They just ran circles around him.” [continued…]

A tip sets the plan in motion — a whispered warning of a North Korean nuclear launch, or of a shipment of biotoxins bound for a Hezbollah stronghold in Lebanon. Word races through the American intelligence network until it reaches U.S. Strategic Command headquarters, the Pentagon and, eventually, the White House. In the Pacific, a nuclear-powered Ohio class submarine surfaces, ready for the president’s command to launch.

alestinian security agents who have been detaining and allegedly torturing supporters of the Islamist organisation Hamas in the West Bank have been working closely with the CIA, the Guardian has learned.

alestinian security agents who have been detaining and allegedly torturing supporters of the Islamist organisation Hamas in the West Bank have been working closely with the CIA, the Guardian has learned.