Nathalia Gjersoe writes: Luc Besson’s latest sci-fi romp, Lucy, is based on the premise that the average person only uses 10% of their brain. This brain-myth has been fodder for books and movies for decades and is a tantalizing plot-device. Alarmingly, however, it seems to be widely accepted as fact. Of those asked, 48% of teachers in the UK, 65% of Americans and 30% of American Psychology students endorsed the myth.

In the movie, Lucy absorbs vast quantities of a nootropic that triggers rampant production of new connections between her neurons. As her brain becomes more and more densely connected, Lucy experiences omniscience, omnipotence and omnipresence. Telepathy, telekinesis and time-travel all become possible.

It’s true that increased connectivity between neurons is associated with greater expertise. Musicians who train for years have greater connectivity and activation of those regions of the brain that control their finger movements and those that bind sensory and motor information. This is the first principle of neural connectivity: cells that fire together wire together.

But resources are limited and the brain is incredibly hungry. It takes a huge amount of energy just to keep it electrically ticking over. There is an excellent TEDEd animation here that explains this nicely. The human adult brain makes up only 2% of the body’s mass yet uses 20% of energy intake. Babies’ brains use 60%! Evolution would necessarily cull any redundant parts of such an expensive organ. [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Attention to the Unseen

The orchestration of attention

The New Yorker: Every moment, our brains are bombarded with information, from without and within. The eyes alone convey more than a hundred billion signals to the brain every second. The ears receive another avalanche of sounds. Then there are the fragments of thoughts, conscious and unconscious, that race from one neuron to the next. Much of this data seems random and meaningless. Indeed, for us to function, much of it must be ignored. But clearly not all. How do our brains select the relevant data? How do we decide to pay attention to the turn of a doorknob and ignore the drip of a leaky faucet? How do we become conscious of a certain stimulus, or indeed “conscious” at all?

For decades, philosophers and scientists have debated the process by which we pay attention to things, based on cognitive models of the mind. But, in the view of many modern psychologists and neurobiologists, the “mind” is not some nonmaterial and exotic essence separate from the body. All questions about the mind must ultimately be answered by studies of physical cells, explained in terms of the detailed workings of the more than eighty billion neurons in the brain. At this level, the question is: How do neurons signal to one another and to a cognitive command center that they have something important to say?

“Years ago, we were satisfied to know which areas of the brain light up under various stimuli,” the neuroscientist Robert Desimone told me during a recent visit to his office. “Now we want to know mechanisms.” Desimone directs the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; youthful and trim at the age of sixty-two, he was dressed casually, in a blue pinstripe shirt, and had only the slightest gray in his hair. On the bookshelf of his tidy office were photographs of his two young children; on the wall was a large watercolor titled “Neural Gardens,” depicting a forest of tangled neurons, their spindly axons and dendrites wending downward like roots in rich soil.

Earlier this year, in an article published in the journal Science, Desimone and his colleague Daniel Baldauf reported on an experiment that shed light on the physical mechanism of paying attention. The researchers presented a series of two kinds of images — faces and houses — to their subjects in rapid succession, like passing frames of a movie, and asked them to concentrate on the faces but disregard the houses (or vice versa). The images were “tagged” by being presented at two frequencies — a new face every two-thirds of a second, a new house every half second. By monitoring the frequencies of the electrical activity of the subjects’ brains with magnetoencephalography (MEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Desimone and Baldauf could determine where in the brain the images were being directed.

The scientists found that, even though the two sets of images were presented to the eye almost on top of each other, they were processed by different places in the brain — the face images by a particular region on the surface of the temporal lobe that is known to specialize in facial recognition, and the house images by a neighboring but separate group of neurons specializing in place recognition.

Most importantly, the neurons in the two regions behaved differently. When the subjects were told to concentrate on the faces and to disregard the houses, the neurons in the face location fired in synchrony, like a group of people singing in unison, while the neurons in the house location fired like a group of people singing out of synch, each beginning at a random point in the score. When the subjects concentrated instead on houses, the reverse happened. [Continue reading…]

Scientists got it wrong on gravitational waves. So what?

Philip Ball writes: It was announced in headlines worldwide as one of the biggest scientific discoveries for decades, sure to garner Nobel prizes. But now it looks likely that the alleged evidence of both gravitational waves and ultra-fast expansion of the universe in the big bang (called inflation) has literally turned to dust.

Last March, a team using a telescope called Bicep2 at the South Pole claimed to have read the signatures of these two elusive phenomena in the twisting patterns of the cosmic microwave background radiation: the afterglow of the big bang. But this week, results from an international consortium using a space telescope called Planck show that Bicep2’s data is likely to have come not from the microwave background but from dust scattered through our own galaxy.

Some will regard this as a huge embarrassment, not only for the Bicep2 team but for science itself. Already some researchers have criticised the team for making a premature announcement to the press before their work had been properly peer reviewed.

But there’s no shame here. On the contrary, this episode is good for science. [Continue reading…]

Why the symbol of life is a loop not a helix

Jamie Davies writes: Here is a remarkable fact about identical twins: they have the same DNA, and therefore the same ‘genetic fingerprint’, yet their actual fingerprints (such as they might leave behind on a murder weapon) are different, and can be told apart in standard police observations. Fingerprints are, of course, produced by the pattern of tiny ridges in skin. So, it would appear that certain fine-scale details of our anatomy cannot be determined by a precise ‘genetic blueprint’.

It isn’t only fine details that seem open to negotiation in this way: anyone who has seen Bonsai cultivation knows how the very genes that would normally build a large tree can instead build a miniature-scale model, given a suitable environment. Bonsai trees aren’t completely scaled down, of course: their cells are normal-sized – it’s just that each component is made with fewer of them.

In the 1950 and ’60s, many children were affected by their mothers taking the drug thalidomide while pregnant, when the drug blocked growth of the internal parts of their limbs. Even though growth of the skin is not directly affected by thalidomide, the very short limbs of affected children were covered by an appropriate amount of skin, not the much larger amount that would be needed to cover a normal limb. The growth of the skin cannot, therefore, just be in response to the command of a hard-wired internal blueprint: something much more adaptive must be going on.

Such observations are not troubling for biological science as such. But they are troubling for a certain picture of how biology works. The symbol for this worldview might be the DNA double helix, its complementary twisting strands evoking other interdependent pairs in life: male and female, form and function, living and non-living. DNA on its own is just a chemical polymer, after all, essential for life but not itself alive. Yet it holds out the promise that we can explain living processes purely in terms of the interactions between simple molecules. [Continue reading…]

Obama creates world’s largest ocean reserve in the Pacific — more than twice the size of California

Vox reports: On Thursday, President Obama created the world’s largest ocean reserve.

The new reserve, an enlargement of the existing Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, nearly quadruples the total amount of US ocean territory that’s protected from commercial fishing, oil drilling, and other activities.

Previously, the monument — a cluster of reserves surrounding seven uninhabited islands south and west of Hawaii — covered about 86,888 square miles. The new monument will cover nearly 490,000 square miles in total, with the gains coming from extending the borders to 200 miles off the coasts of Wake Island, Jarvis Island, and Johnston Atoll. This is as far as the US government is permitted to protect, according to international law.

Despite the huge gains, though, the new monument is considerably smaller than the one Obama originally proposed in July, which would have been 782,000 square miles, and extended the protected zone around four other islands as well. Opposition from the commercial tuna fishing industry during the public comment period led to the shrinkage.

At the moment, there’s no drilling and not that much fishing in the newly protected area — so the reserve won’t be hugely impactful at the start. Still, it’s a big step forward in proactively protecting marine habitats on a massive scale. [Continue reading…]

We are more rational than those who nudge us

Steven Poole writes: Humanity’s achievements and its self-perception are today at curious odds. We can put autonomous robots on Mars and genetically engineer malarial mosquitoes to be sterile, yet the news from popular psychology, neuroscience, economics and other fields is that we are not as rational as we like to assume. We are prey to a dismaying variety of hard-wired errors. We prefer winning to being right. At best, so the story goes, our faculty of reason is at constant war with an irrational darkness within. At worst, we should abandon the attempt to be rational altogether.

The present climate of distrust in our reasoning capacity draws much of its impetus from the field of behavioural economics, and particularly from work by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the 1980s, summarised in Kahneman’s bestselling Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011). There, Kahneman divides the mind into two allegorical systems, the intuitive ‘System 1’, which often gives wrong answers, and the reflective reasoning of ‘System 2’. ‘The attentive System 2 is who we think we are,’ he writes; but it is the intuitive, biased, ‘irrational’ System 1 that is in charge most of the time.

Other versions of the message are expressed in more strongly negative terms. You Are Not So Smart (2011) is a bestselling book by David McRaney on cognitive bias. According to the study ‘Why Do Humans Reason?’ (2011) by the cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, our supposedly rational faculties evolved not to find ‘truth’ but merely to win arguments. And in The Righteous Mind (2012), the psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls the idea that reason is ‘our most noble attribute’ a mere ‘delusion’. The worship of reason, he adds, ‘is an example of faith in something that does not exist’. Your brain, runs the now-prevailing wisdom, is mainly a tangled, damp and contingently cobbled-together knot of cognitive biases and fear.

This is a scientised version of original sin. And its eager adoption by today’s governments threatens social consequences that many might find troubling. A culture that believes its citizens are not reliably competent thinkers will treat those citizens differently to one that respects their reflective autonomy. Which kind of culture do we want to be? And we do have a choice. Because it turns out that the modern vision of compromised rationality is more open to challenge than many of its followers accept. [Continue reading…]

Ants are cool but teach us nothing

E.O. Wilson writes: For nearly seven decades, starting in boyhood, I’ve studied hundreds of kinds of ants around the world, and this qualifies me, I believe, to offer some advice on ways their lives can be applied to ours. I’ll start with the question I’m most often asked: “What can I do about the ants in my kitchen?” My response comes from the heart: Watch your step, be careful of little lives. Ants especially like honey, tuna and cookie crumbs. So put down bits of those on the floor, and watch as the first scout finds the bait and reports back to her colony by laying an odor trail. Then, as a little column follows her out to the food, you will see social behavior so strange it might be on another planet. Think of kitchen ants not as pests or bugs, but as your personal guest superorganism.

Another question I hear a lot is, “What can we learn of moral value from the ants?” Here again I will answer definitively: nothing. Nothing at all can be learned from ants that our species should even consider imitating. For one thing, all working ants are female. Males are bred and appear in the nest only once a year, and then only briefly. They are pitiful creatures with wings, huge eyes, small brains and genitalia that make up a large portion of their rear body segment. They have only one function in life: to inseminate the virgin queens during the nuptial season. They are built to be robot flying sexual missiles. Upon mating or doing their best to mate, they are programmed to die within hours, usually as victims of predators.

Many kinds of ants eat their dead — and their injured, too. You may have seen ant workers retrieve nestmates that you have mangled or killed underfoot (accidentally, I hope), thinking it battlefield heroism. The purpose, alas, is more sinister. [Continue reading…]

Will misogyny bring down the atheist movement?

Mark Oppenheimer writes: Several women told me that women new to the movement were often warned about the intentions of certain older men, especially [Michael] Shermer [the founder of Skeptic magazine]. Two more women agreed to go on the record, by name, with their Shermer stories… These stories help flesh out a man who, whatever his progressive views on science and reason, is decidedly less evolved when it comes to women.

Yet Shermer remains a leader in freethought — arguably the leader. And in his attitudes, he is hardly an exception. Hitchens, the best-selling author of God Is Not Great, who died in 2011, wrote a notorious Vanity Fair article called “Why Women Aren’t Funny.” Richard Dawkins, another author whose books have brought atheism to the masses, has alienated many women — and men — by belittling accusations of sexism in the movement; he seems to go out of his way to antagonize feminists generally, and just this past July 29 he tweeted, “Date rape is bad. Stranger rape at knifepoint is worse. If you think that’s an endorsement of date rape, go away and learn how to think.” And Penn Jillette, the talking half of the Penn and Teller duo, famously revels in using words like “cunt.”

The reality of sexism in freethought is not limited to a few famous leaders; it has implications throughout the small but quickly growing movement. Thanks to the internet, and to popular authors like Dawkins, Hitchens, and Sam Harris, atheism has greater visibility than at any time since the 18th-century Enlightenment. Yet it is now cannibalizing itself. For the past several years, Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and online forums have become hostile places for women who identify as feminists or express concern about widely circulated tales of sexism in the movement. Some women say they are now harassed or mocked at conventions, and the online attacks — which include Jew-baiting, threats of anal rape, and other pleasantries — are so vicious that two activists I spoke with have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. One of these women has been bedridden for two years.

To those outside the community, freethought would seem an unlikely candidate for this sort of internal strife. Aren’t atheists and agnostics supposed to be liberal, forward-thinking types? But from the beginning, there has been a division in freethought between the humanists, who see atheism as one part of a larger progressive vision for society, and the libertarians, for whom the banishment of God sits comfortably with capitalism, gun rights, and free-speech absolutism. One group sees men like Michael Shermer as freethought’s big problem, while the other sees defending them as crucial to freethought’s mission. [Continue reading…]

How ancient DNA is rewriting human history

Michael White writes: There are no written records of the most important developments in our history: the transition from hunting and gathering to farming, the initial colonization of regions outside Africa, and, most crucially, the appearance of modern humans and the vanishing of archaic ones. Our primary information sources about these “pre-historic” events are ancient tools, weapons, bones, and, more recently, DNA. Like an ancient text that has picked up interpolations over the millennia, our genetic history can be difficult to recover from the DNA of people alive today. But with the invention of methods to read DNA taken from ancient bones, we now have access to much older copies of our genetic history, and it’s radically changing how we understand our deep past. What seemed like an episode of Lost turns out to be much more like Game of Thrones: instead of a story of small, isolated groups that colonized distant new territory, human history is a story of ancient populations that migrated and mixed all over the world.

There is no question that most human evolutionary history took place in Africa. But by one million years ago—long before modern humans evolved — archaic human species were already living throughout Asia and Europe. By 30,000 years ago, the archaic humans had vanished, and modern humans had taken their place. How did that happen?

From the results of early DNA studies in the late 1980s and early ’90s, scientists argued that anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa, and then expanded into Asia, Oceania, and Europe, beginning about 60,000 years ago. The idea was that modern humans colonized the rest of the world in a succession of small founding groups — each one a tiny sampling of the total modern human gene pool. These small, isolated groups settled new territory and replaced the archaic humans that lived there. As a result, humans in different parts of the world today have their own distinctive DNA signature, consisting of the genetic quirks of their ancestors who first settled the area, as well as the genetic adaptations to the local environment that evolved later.

There are very few isolated branches of the human family tree. People in nearly every part of the world are a product of many different ancient populations, and sometimes surprisingly close relationships span a wide geographical distance.This view of human history, called the “serial founder effect model,” has big implications for our understanding of how we came to be who we are. Most importantly, under this model, genetic differences between geographically separated human populations reflect deep branchings in the human family tree, branches that go back tens of thousands of years. It also declares that people have evolutionary adaptations that are matched to their geographical area, such as lighter skin in Asians and Europeans or high altitude tolerance among Andeans and Tibetans. With a few exceptions, such as the genetic mixing after Europeans colonized the Americas, our geography reflects our deep ancestry.

Well, it’s time to scrap this picture of human history. [Continue reading…]

Robert Sapolsky: Are humans just another primate?

The manufacturers of the world’s handpans don’t want to turn to mass production

Ilana E. Strauss writes: The handpan may look like a Stone Age relic, but it was actually invented about a decade ago by Swiss artists Felix Rohner and Sabina Schärer. The two were steelpan makers, and they came up with a new instrument, which they christened the “Hang” meaning “hand” in Bernese German.

Rohner and Schärer formed their company, PANArt, to sell their creations in 2000. Requests started pouring in, and soon they couldn’t meet demand. They received thousands of inquiries annually, but they only made a few hundred instruments each year.

The artists didn’t want to mass-produce their handpans, so they did something novel: They required prospective customers to write hand-written letters. A chosen few were then invited to the PANArt workshop in Switzerland (they had to furnish their own travel expenses), where they bought their instruments in person. While there, buyers learned about the history and use of the Hang, as well as how to care for it. [Continue reading…]

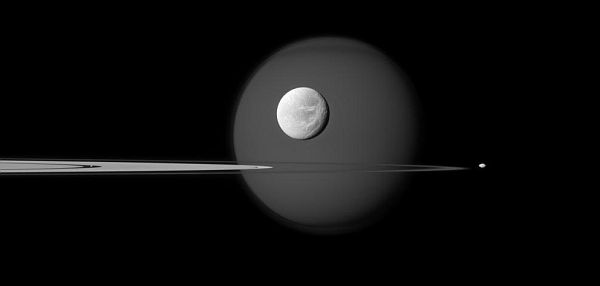

Out of this world: Titan, Dione, Pandora, and Pan

The only thing the New Year marks for sure is our place in the Solar System as we circle the Sun.

Here’s a reminder of how unfamiliar and other worldly this place in space, our home in the galaxy, our corner of the universe, really is: a view of four of Saturn’s moons in descending order of size — Titan in the background behind Dione, with Pandora over to the right, and Pan nothing more than a speck on the left nestled in the Encke Gap of the A ring.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

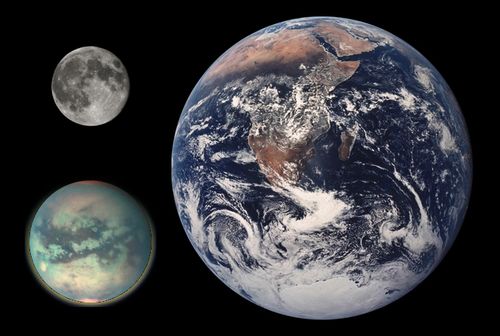

Although frigidly cold, Titan has some Earth-like features — a climate with wind and rain, and surface features such as dunes, rivers, lakes and seas. For scale, this is how Titan would look if placed alongside the Moon and the Earth:

Random acts of secret generosity

Kate Murphy writes: If you place an order at the Chick-fil-A drive-through off Highway 46 in New Braunfels, Tex., it’s not unusual for the driver of the car in front of you to pay for your meal in the time it took you to holler into the intercom and pull around for pickup.

“The people ahead of you paid it forward,” the cashier will chirp as she passes your food through the window.

Confused, you look ahead at the car — it could be a mud-splashed monster truck, Mercedes or minivan — which at this point is turning onto the highway. The cashier giggles, you take your food and unless your heart is irreparably rotted from cynicism and snark, you feel touched.

You could chalk it up to Southern hospitality or small town charm. But it’s just as likely the preceding car will pick up your tab at a Dunkin’ Donuts drive-through in Detroit or a McDonald’s drive-through in Fargo, N.D. Drive-through generosity is happening across America and parts of Canada, sometimes resulting in unbroken chains of hundreds of cars paying in turn for the person behind them.

This is taking place at a time when the nation’s legislators can’t speak a civil word unless reading from Dr. Seuss. “We really don’t know why it’s happening but if I had to guess, I’d say there is just a lot of stuff going on in the country that people find discouraging,” said Mark Moraitakis, director of hospitality at Chick-fil-A, which is based in Atlanta. “Paying it forward is a way to counteract that.” [Continue reading…]

Star Axis, a masterpiece forty years in the making

Ross Andersen writes: On a hot afternoon in late June, I pulled to the side of a two-lane desert highway in eastern New Mexico, next to a specific mile marker. An hour earlier, a woman had told me to wait for her there at three o’clock, ‘sharp’. I edged as far off the shoulder as I could, to avoid being seen by passing traffic, and parked facing the wilderness. A sprawling, high desert plateau was set out before me, its terrain a maze of raised mesas, sandstone survivors of differential erosion. Beyond the plateau, the landscape stretched for miles, before dissolving into a thin strip of desert shimmer. The blurry line marked the boundary between the land and one of the biggest, bluest skies I’d ever seen.

I had just switched off the ignition when I spotted a station wagon roaring toward me from the plateau, towing a dust cloud that looked like a miniature sandstorm. Its driver was Jill O’Bryan, the wife and gatekeeper of Charles Ross, the renowned sculptor. Ross got his start in the Bay Area art world of the mid‑1960s, before moving to New York, where he helped found one of SoHo’s first artist co-ops. In the early 1970s, he began spending a lot of time here in the New Mexico desert. He had acquired a remote patch of land, a mesa he was slowly transforming into a massive work of land art, a naked-eye observatory called Star Axis. Ross rarely gives interviews about Star Axis, but when he does he describes it as a ‘perceptual instrument’. He says it is meant to offer an ‘intimate experience’ of how ‘the Earth’s environment extends into the space of the stars’. He has been working on it for more than 40 years, but still isn’t finished.

I knew Star Axis was out there on the plateau somewhere, but I didn’t know where. Its location is a closely guarded secret. Ross intends to keep it that way until construction is complete, but now that he’s finally in the homestretch he has started letting in a trickle of visitors. I knew, going in, that a few Hollywood celebrities had been out to Star Axis, and that Ross had personally showed it to Stewart Brand. After a few months of emails, and some pleading on my part, he had agreed to let me stay overnight in it.

Once O’Bryan was satisfied that I was who I said I was, she told me to follow her, away from the highway and into the desert. I hopped back into my car, and we caravanned down a dirt road, bouncing and churning up dust until, 30 minutes in, O’Bryan suddenly slowed and stuck her arm out her driver’s side window. She pointed toward a peculiar looking mesa in the distance, one that stood higher than the others around it. Notched into the centre of its roof was a granite pyramid, a structure whose symbolic power is as old as history.

Twenty minutes later, O’Bryan and I were parked on top of the mesa, right at the foot of the pyramid and she was giving me instructions. ‘Don’t take pictures,’ she said, ‘and please be vague about the location in your story.’ She also told me not to use headlights on the mesa top at night, lest their glow tip off unwanted visitors. There are artistic reasons for these cloak-and-dagger rituals. Like any ambitious artist, Ross wants to polish and perfect his opus before unveiling it. But there are practical reasons, too. For while Star Axis itself is nearly built, its safety features are not, and at night the pitch black of this place can disorient you, sending you stumbling into one of its chasms. There is even an internet rumour — Ross wouldn’t confirm it — that the actress Charlize Theron nearly fell to her death here. [Continue reading…]

Video: The lives we pass by

Painting the way to the Moon

Wild River Review: Ed Belbruno doesn’t sit still easily. On a sunny, winter afternoon, he perches at the edge of his sofa talking about his latest book, Fly Me to the Moon (Princeton University Press), and about chaos. Specifically chaos theory. In his book, Belbruno tells the story of how he used chaos theory to get the world’s first spaceship (a Japanese spaceship named Hiten, which means “A Buddhist Angel that Dances in Heaven”) to the moon without using fuel. To illustrate a point, his hands move through the air, creating a sunlit swirl of fine dust particles.

Belbruno’s own paintings adorn the walls of his living room, one of which gave him the solution for Hiten. In the corner, tubes of oil paint lie on a drafting table next to an easel exhibiting his latest work, gorgeous splashes of color representing microwaves.

“Chaos is a way to describe the motion of an object where the motion appears to be very unpredictable,” he says. “Some things are not chaotic and some things are.”

“For example,” he continues. “If you look at a leaf falling to the ground on a windy day, it doesn’t fall like a piece of lead rocketing to the ground. It floats. And if the wind catches that leaf, it will dart around from place to place, and the resulting path is not something you know ahead of time. So from moment to moment, you cannot say where the leaf will go. Therefore, chaos has a sense of unpredictability to it. You could say, ’Well does it mean that I can’t really know where something is going?’ In a sense you can’t, because you have to know every little detail of the atmosphere of the earth, about how the wind varies from point to point, and we don’t. The same holds true for space and the orbit of the planets.”

Belbruno knows that out of seeming chaos, a path can be found between two points. [Continue reading…]

Celebrating life on Earth

The Mayan calendar did not predict the end of the world

A Mayan elder explains in more detail how the Mayan cyclical calendars worked.

It’s always worth being reminded that the real Americans inhabited this continent long before the Europeans arrived.

Tim Padgett writes: I once took a Classics professor friend of mine, a real Hellenophile, to the majestic Maya ruins of Palenque in southern Mexico. I wanted him to see why the Maya, thanks to their advanced astronomy, mathematics and cosmology, are considered the Greeks of the New World. As we entered the Palace there, my friend stopped, surprised, and said, “Corbel arches!” That’s the kind of precocious architecture you find at famous ancient Greek sites like Mycenae — and seeing it at Palenque made him acknowledge that maybe the Greeks could be considered the Maya of the Old World.

Today, Dec. 21, we’re all standing under those Corbel arches, celebrating one of civilization’s more sublime accomplishments, the Maya calendar. The 2012 winter solstice marks the end of a 5,125-year creation cycle and the hopeful start of another — and not the apocalyptic end that so many wing nuts rave about. (That comes next month, when our wing nuts in Washington send us over the fiscal cliff.) Understandably, this Maya milestone is a source of Latin American and especially Mexican pride. As teacher Jaime Escalante tells the Mexican-American kids he turns into calculus wizards in the 1988 film Stand and Deliver: “Did you know that neither the Greeks nor the Romans were capable of using the concept of zero? It was your ancestors, the Mayas, who first contemplated it…True story.”

But, unfortunately, most Americans ignore that record and focus on the doomsday nonsense that a crowd of pseudo-scholars has tied to the Maya calculations. It’s part and parcel of the western world’s condescending approach to pre-Columbian society—typified by the popular canard that if the Maya did rival the Greeks in any arena, then space aliens must have shown them how. It also reflects the maddening American disregard, if not disdain, for Mexico and Latin America, which persists even today as Escalante’s now grown-up Chicano students and the rest of the Latino community prove their political clout. So since today is all about new beginnings — and since Mexico itself is endeavoring a fresh start right now — we also ought to consider an overhaul of the tiresomely arrogant and indifferent way we look at the world south of the border. [Continue reading…]