Candor cost Gen Stanley McChrystal his job as US commander in Afghanistan, while President Obama was credited with a political masterstroke — replacing the general with a loose tongue with a general with a golden tongue.

Candor cost Gen Stanley McChrystal his job as US commander in Afghanistan, while President Obama was credited with a political masterstroke — replacing the general with a loose tongue with a general with a golden tongue.

But maybe Bob Woodward’s new book, Obama’s Wars, would not be treated as a source of revelations if more attention had been paid to what McChrystal said than the way he said it.

The renegade general’s portrayal of a president who “didn’t seem very engaged,” suggests that Obama’s claim as both candidate and president — that Afghanistan was a war of necessity — was a political posture that would eventually prove to be untenable.

In June, Michael Hastings wrote:

Even though he had voted for Obama, McChrystal and his new commander in chief failed from the outset to connect. The general first encountered Obama a week after he took office, when the president met with a dozen senior military officials in a room at the Pentagon known as the Tank. According to sources familiar with the meeting, McChrystal thought Obama looked “uncomfortable and intimidated” by the roomful of military brass. Their first one-on-one meeting took place in the Oval Office four months later, after McChrystal got the Afghanistan job, and it didn’t go much better. “It was a 10-minute photo op,” says an adviser to McChrystal. “Obama clearly didn’t know anything about him, who he was. Here’s the guy who’s going to run his fucking war, but he didn’t seem very engaged. The Boss was pretty disappointed.”

Bob Woodward (no relation to me) now portrays a commander in chief intensely focused on getting out of Afghanistan and surrounded by advisers who fought with each other.

The president concluded from the start that “I have two years with the public on this” and pressed advisers for ways to avoid a big escalation, the book says. “I want an exit strategy,” he implored at one meeting. Privately, he told Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. to push his alternative strategy opposing a big troop buildup in meetings, and while Mr. Obama ultimately rejected it, he set a withdrawal timetable because, “I can’t lose the whole Democratic Party.”

But Mr. Biden is not the only one who harbors doubts about the strategy’s chances for success. Lt. Gen. Douglas E. Lute, the president’s Afghanistan adviser, is described as believing that the president’s review did not “add up” to the decision he made. Richard C. Holbrooke, the president’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, is quoted saying of the strategy that “it can’t work.”

Obama’s problem: either an exit strategy was a necessity or the war was a necessity but he couldn’t argue for both.

Besides, whatever he might actually believe, he had already boxed himself in by pursuing a political strategy that hinged on his ability to portray himself as an opponent to the war in Iraq who was not an opponent of war per se.

The war in Afghanistan was Obama’s shield against Republican attacks. “I am not opposed to all wars. I’m opposed to dumb wars,” he said in 2002 when laying out his credentials as an un-antiwar Illinois State Senator.

If Obama as a candidate and as president was to have been more candid, he might have expanded on a theme he touched on only briefly — his affinity with Ronald Reagan but more specifically their apparent shared belief that American wars are best fought in secret using mercenaries.

While the reporting on Woodward’s book is likely to focus on the infighting surrounding a president who appears to lack conviction, the New York Times report also has new details on a covert war in which it seems likely that the Durand Line (dividing Afghanistan and Pakistan) means as little to the US government as it does to the Pashtun people.

[Obama’s Wars] reports that the CIA has a 3,000-man “covert army” in Afghanistan called the Counterterrorism Pursuit Teams, or CTPT, mostly Afghans who capture and kill Taliban fighters and seek support in tribal areas. Past news accounts have reported that the CIA has a number of militias, including one trained on one of its compounds, but not the size of the covert army.

I guess they couldn’t call them the neo-mujahadeen — or what might be even more fitting: the Afghan Contras.

As a Journeyman TV report revealed earlier this year and as has been demonstrated many times before, US-backed militias often end up becoming death squads.

Update: Justin Elliott at Salon picks up the same theme and includes a paragraph that appeared in an earlier version of the New York Times report:

Mr. Woodward reveals the code name for the CIA.’s drone missile campaign in Pakistan, Sylvan Magnolia, and writes that the White House was so enamored of the program that Mr. Emanuel would regularly call the CIA director, Leon E. Panetta, asking, “Who did we get today?”

The White House chief of staff sounds just like former President Bush with his adolescent, comic-book conception of push-button warfare. Hellfire missiles don’t indiscriminately shred human bodies and destroy homes — they “get” targets and the targets can be chalked up on a scoreboard.

Did an editor at the New York Times decide that the man who might be hoping to become the next mayor of Chicago should be saved some embarrassment?

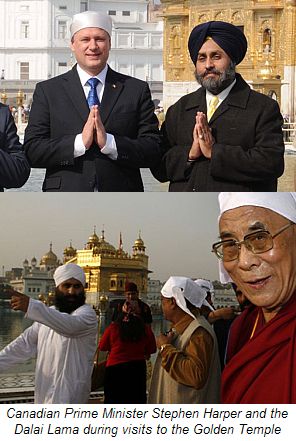

The Golden Temple, a sprawling and serene complex of gleaming gold and polished marble that is the spiritual center of the Sikh religion, is one of India’s most popular tourist attractions. Revered by Indians of all faiths, it is a cherished emblem of India’s religious diversity. So it was no surprise when the gold-plated marvel was promoted as the likely third stop on President Obama’s visit to India, scheduled for early November.

The Golden Temple, a sprawling and serene complex of gleaming gold and polished marble that is the spiritual center of the Sikh religion, is one of India’s most popular tourist attractions. Revered by Indians of all faiths, it is a cherished emblem of India’s religious diversity. So it was no surprise when the gold-plated marvel was promoted as the likely third stop on President Obama’s visit to India, scheduled for early November.

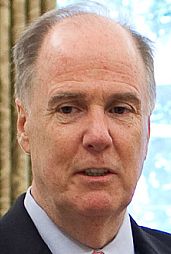

Undaunted by the revelations from Bob Woodward’s book, Obama’s Wars, President Obama is replacing National Security Adviser Gen James Jones with his deputy, Tom Donilon.

Undaunted by the revelations from Bob Woodward’s book, Obama’s Wars, President Obama is replacing National Security Adviser Gen James Jones with his deputy, Tom Donilon. The disclosure of the details of a letter reportedly sent by President Barack Obama last week to Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, will cause Palestinians to be even more skeptical about U.S. and Israeli roles in the current peace talks.

The disclosure of the details of a letter reportedly sent by President Barack Obama last week to Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, will cause Palestinians to be even more skeptical about U.S. and Israeli roles in the current peace talks. Candor cost Gen Stanley McChrystal his job as US commander in Afghanistan, while President Obama was credited with a political masterstroke — replacing the general with a loose tongue with a general with a golden tongue.

Candor cost Gen Stanley McChrystal his job as US commander in Afghanistan, while President Obama was credited with a political masterstroke — replacing the general with a loose tongue with a general with a golden tongue.