Yousuf v. Samantar is the first human rights suit arising from abuses committed in Somalia under the brutal regime of Siad Barre. It is currently pending before the Supreme Court, where an odd coalition of defenders has filed briefs on behalf of the defendant, Mohammed Samantar, a prime minister under Barre and an alleged war criminal.

Among his defenders are five pro-Israel organizations — the American Jewish Congress, the Zionist Organization of America, the American Association of Jewish Lawyers And Jurists, Agudath Israel of America, and the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America in Support of Petitioner — each with a professed interest in keeping Samantar out of court. Allowing the case to proceed, they warn, would set an inviting precedent for Israel’s detractors in the human rights community, exposing current and former Israeli officials to an avalanche of litigation.

This suit was brought by the Center for Justice and Accountability and pro bono co-counsel Cooley Godward Kronish LLP in 2004 on behalf of five torture survivors: Bashe Abdi Yousuf, a young business man detained, tortured, and kept in solitary confinement for over six years; Aziz Mohamed Deria, whose father and brother were abducted by officials and never seen again; John Doe I, whose two brothers were summarily executed by soldiers; Jane Doe, a university student detained by officials, raped 15 times, and put in solitary confinement for over three years; and John Doe II, who was imprisoned for his clan affiliation and was shot by a firing squad, but miraculously survived by hiding under other dead bodies.

A strange alliance at the Supreme Court

By Sam Singer, War in Context, April 4, 2010

Mohammed Ali Samantar is the only living vestige of the Barre regime, the last government in two decades to exercise central control over Somalia and, not coincidentally, the last that was impudent enough to try. When Siad Barre was finally overthrown in 1991, Samantar, who had served as defense minister and prime minister, fled, in a storm of bullets, to Italy. He eventually made his way to Fairfax, Virginia, where he lived in suburban obscurity until a group of Somali nationals discovered him, hired a lawyer, and sued for damages. According to his accusers, the Barre regime committed unforgivable acts of violence against them and their families, offenses spanning a range of brutality from arbitrary detention, to torture, rape and extrajudicial killing. Samantar was allegedly aware of the crimes being perpetrated against civilians and yet failed to stop them. The suit was dismissed by a federal district court and then reinstated by the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. It is now pending before the Supreme Court, where a peculiar coalition of defenders is urging reversal. Among them, to the confusion of some observers, are five prominent pro-Israel organizations, each with a professed interest in keeping Samantar out of court. In joint amicus briefs, the groups insist that as a former government official, Samantar should be immune from suit. To hold otherwise, they warn, would violate international law and set an inviting precedent for Israel’s enemies and their supporters in the human rights community.

Mohammed Ali Samantar is the only living vestige of the Barre regime, the last government in two decades to exercise central control over Somalia and, not coincidentally, the last that was impudent enough to try. When Siad Barre was finally overthrown in 1991, Samantar, who had served as defense minister and prime minister, fled, in a storm of bullets, to Italy. He eventually made his way to Fairfax, Virginia, where he lived in suburban obscurity until a group of Somali nationals discovered him, hired a lawyer, and sued for damages. According to his accusers, the Barre regime committed unforgivable acts of violence against them and their families, offenses spanning a range of brutality from arbitrary detention, to torture, rape and extrajudicial killing. Samantar was allegedly aware of the crimes being perpetrated against civilians and yet failed to stop them. The suit was dismissed by a federal district court and then reinstated by the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. It is now pending before the Supreme Court, where a peculiar coalition of defenders is urging reversal. Among them, to the confusion of some observers, are five prominent pro-Israel organizations, each with a professed interest in keeping Samantar out of court. In joint amicus briefs, the groups insist that as a former government official, Samantar should be immune from suit. To hold otherwise, they warn, would violate international law and set an inviting precedent for Israel’s enemies and their supporters in the human rights community.

The arrival of the Israel lobby adds geopolitical intrigue to a case that already read like a Ludlum thriller. And because it speaks to real and immediate consequences, it lends concreteness to a discussion that would have otherwise carried on in the abstract. It is one thing for a lawyer to appeal to legal authority for the proposition that the courts of one nation ought not sit in judgment of the acts of another; it is quite another for five groups purporting to represent the interests of the Israeli government to advise that doing so in this case would be to declare open season on Israeli officials in US courts.

It is not without some irony that organizations claiming to represent Israel, a state conceived in the wake of unprecedented state-sponsored violence, find their wagon hitched to the cause of an alleged war criminal. Nor does the position square, at least not at first glance, with less expansive interpretations of sovereign immunity advanced by the lobby’s constituents in the past. Just this year, Israeli victims of rocket fire on the Lebanese border sued the Iranian government, by way of its central banks, on the theory that it provided material support to Hezbollah, the source of the rockets. Last December, a pro-Israel group in Europe sued leaders of Hamas in a Belgium court, invoking what it described as the court’s “universal” jurisdiction over cases arising from war crimes. In both cases, sovereign immunity was an obstacle standing between Israeli interests and a favorable judgment; here, in Samantar’s case, supporters of Israel invoke it as a shield.

In fact, Israel is far more likely to find itself on the receiving end of a human rights suit. According to one report, nearly 1,000 suits have been filed globally against Israeli officials and military personnel alleging war crimes and other abuses. The defense ministry expects some 1,500 more will follow, many stemming from military operations in the coastal territories, but also some taking aim at the less violent aspects of Israeli anti-terror strategy, including one suit describing the security fence as a “crime against humanity.” An Israeli newspaper published a “wanted” list of current and former officials who are among the common named defendants. The list, which was republished in briefs to the Court, reads like a who’s who in Israeli political and military history. The forums for these suits vary, but they commonly feature developed Western countries that have lowered the drawbridge for human rights litigants. Steering many of the cases are nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), some based in the Middle East with ties to the Palestinian government, others based in the West and backed by the likes of the Center for Constitutional Rights and George Soros’s Open Society Institute.

In these suits supporters of Israel see pretext. They describe a more sinister objective, a coordinated effort to bring Israeli officials into federal courtrooms. The idea is to delegitimize Israel, but not before dragging officials through an invasive and costly discovery process. Do it enough and Israeli officials will start thinking twice before traveling to the United States, or, worse yet, before assuming roles that could expose them to suit. Defense experts believe the strategy fits the definition of “lawfare,” think-tank speak for the use of legal methods to achieve military goals.

In the immediate term, the briefs warn, relations between the US and Israel will suffer. Like any partnership, the US/Israeli alliance benefits from a rich and ongoing exchange of people and ideas. For the exchange to thrive, current and former Israeli officials must be able to travel to and within the United States without fear of being served with a lawsuit. By way of illustration, the American Jewish Congress recounts the story of Moshe Ya’alon, a retired Israeli general who was recently summoned to court upon arriving in Washington, D.C. for a think tank forum. The complaint, which sought damages for civilian deaths resulting from a battle on the Lebanese border between Israel and Hezbollah, was perfunctory. With respect to Ya’alon, it alleged only that he served in the army chain-of-command during the relevant period. The district court dismissed the case on jurisdictional grounds and the D.C. Circuit affirmed, concluding that the immunity of a foreign state extends to its former officials. Ya’alon never had to step foot in a courtroom. Now suppose that instead of Washington, he had been served with the suit 15 minutes away, in Arlington, Virginia. In that event the dismissal of his suit would have been appealed to the Fourth Circuit, which, as we learned in Samantar’s case, does not share the D.C. Circuit’s view on official immunity. In other words, had Ya’alon booked a hotel across the river, he might well still be there today.

A Statutory Nightmare

Naturally, US-Israeli relations didn’t figure into the Supreme Court’s questioning at oral arguments. The justices had assembled to resolve a disagreement among the federal circuit courts over whether sovereign immunity extends to officials. Accordingly, they trained their focus on Samantar and his theory of the case, which rests on the off-stated maxim that one equal has no dominion over another equal. That this saying, which encapsulates the principle of sovereign immunity, is most commonly recited in Latin suggests something about its vintage. It is as close to a truism as a proposition can come in a foggy discipline like international law, and it is an animating principle of the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act (FSIA). That law changed the way US courts process suits against foreign governments. Before 1976, a court needed the go-ahead from the State Department before docketing such cases. When this approach proved unwieldy, Congress vested gate-keeping authority in the federal courts and then cabined it by stripping them of jurisdiction over suits against foreign states that don’t fit within a narrow set of exceptions.

Until recently it was generally accepted that these same protections applied to foreign officials. After all, a suit against a foreign official acting on behalf of a state is effectively a suit against the state. True, the caption may list the Minister of Defense rather than the Ministry of Defense, and the plaintiff may have his sights set on a personal bank account rather than the national treasury, but in either case the court is sitting in judgment of the state’s actions. It has intuitive appeal, this idea. It also has the support of the majority of the federal circuits.

But as the Fourth Circuit pointed out below, the argument is without support in the one place it needs it most–the text of the FSIA. FSIA extends sovereign immunity to “foreign states” as well as their “agencies and instrumentalities”, but it remains conspicuously silent on the matter of foreign officials. For supporters of broad immunity, this omission is proof that the identity of interests between a foreign sovereign and its officials is self-evident. Congress, they argue, had no reason to split hairs, to try to distinguish the indistinguishable. Opponents, who harbor a less attenuated view, insist that if Congress wanted to extend immunity to foreign officials, it would have said so.

The theory that foreign officials are immune from suit encounters an more mystifying problem in the Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA), a federal law that permits victims of state-sponsored torture to bring suit in the United States against culpable foreign officials. The TVPA is one of the statutes supplying the cause of action in the suit against Samantar, but that’s not why it’s important. Rather, as Justice Kennedy pointed out during oral arguments, the text of the TVPA appears to make a mockery of the proposition that foreign officials are never amenable to suit in U.S courts. To read the law any other way would be to watch it evaporate, an entire congressional enactment rendered useless, leaving torture victims a right without a remedy. The Court, Justice Kennedy reminds, is not in the business of reading entire statutes out of existence.

Supporters of immunity for foreign officials counter that allowing the case to proceed against Samantar would be just as devastating for FSIA. As a preoccupation of Justice Breyer’s, this argument soaked up a fair amount of the Court’s time. The consensus is that opening officials to suit would allow litigants to undermine the intent of the FSIA without actually violating it. In Ya’alon’s case, instead of suing the Ministry of Defense, a lawyer with his wits about him would simply name Ya’alon, the former head of army intelligence, and the suit would survive. “What you are saying,” Breyer concluded, “is that FSIA is only good against a bad lawyer.”

Hedging, counsel for the plaintiffs reminded the Court that jurisdiction is not the only hurdle between a foreign official and liability. Once a plaintiff establishes jurisdiction, there are other age-old immunity doctrines that shield foreign officials from suit. There is the head of state doctrine, for instance, which protects current and former leaders from prosecution and civil liability, or the doctrine of diplomatic immunity, a similar, if more controversial, safeguard for diplomats and their staff. But there is no small difference between immunity from suit and immunity from liability. To have the former without the latter is to have comfort without convenience; it is, so to speak, the difference between putting up and showing up.

The Supreme Court is thus left to choose between two seemingly impossible outcomes. Extend sovereign immunity to foreign officials and the Torture Victim Protection Act is gutted, along with U.S. credibility in the human rights community. Expose them to suit and make hash of one of the core objectives of the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act—saving key allies the expense and embarrassment of defending national security decisions in US courts. To the extent possible, courts generally try to read conflicting statutes in a way that gives effect to both. But even with so much hanging in the balance, coexistence between the TVPA and the FSIA appears impossible. Unimpressed and evidently undecided, the justices took the case under advisement.

Sam Singer is a 2009 graduate of Emory Law School and a Staff Law Clerk for the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. His commentaries on law and politics have appeared in various publications, including The Beachwood Reporter and Culturekiosque.com. He has also reported and written articles for The Chicago Tribune and Market News International.

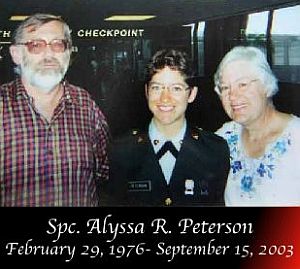

The 27-year-old’s parents didn’t even know their daughter was in Iraq until they were informed of her death. The fact that she committed suicide was concealed by the military for several more years — the most likely reason for the cover-up being that it was Peterson’s unwillingness to participate in torture that drove her to take her own life.

The 27-year-old’s parents didn’t even know their daughter was in Iraq until they were informed of her death. The fact that she committed suicide was concealed by the military for several more years — the most likely reason for the cover-up being that it was Peterson’s unwillingness to participate in torture that drove her to take her own life.

Mohammed Ali Samantar is the only living vestige of the Barre regime, the last government in two decades to exercise central control over Somalia and, not coincidentally, the last that was impudent enough to try. When Siad Barre was finally overthrown in 1991, Samantar, who had served as defense minister and prime minister, fled, in a storm of bullets, to Italy. He eventually made his way to Fairfax, Virginia, where he lived in suburban obscurity until a group of Somali nationals discovered him, hired a lawyer, and sued for damages. According to his accusers, the Barre regime committed unforgivable acts of violence against them and their families, offenses spanning a range of brutality from arbitrary detention, to torture, rape and extrajudicial killing. Samantar was allegedly aware of the crimes being perpetrated against civilians and yet failed to stop them. The suit was dismissed by a federal district court and then reinstated by the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. It is now pending before the Supreme Court, where a peculiar coalition of defenders is urging reversal. Among them, to the confusion of some observers, are five prominent pro-Israel organizations, each with a professed interest in keeping Samantar out of court. In joint amicus briefs, the groups insist that as a former government official, Samantar should be immune from suit. To hold otherwise, they warn, would violate international law and set an inviting precedent for Israel’s enemies and their supporters in the human rights community.

Mohammed Ali Samantar is the only living vestige of the Barre regime, the last government in two decades to exercise central control over Somalia and, not coincidentally, the last that was impudent enough to try. When Siad Barre was finally overthrown in 1991, Samantar, who had served as defense minister and prime minister, fled, in a storm of bullets, to Italy. He eventually made his way to Fairfax, Virginia, where he lived in suburban obscurity until a group of Somali nationals discovered him, hired a lawyer, and sued for damages. According to his accusers, the Barre regime committed unforgivable acts of violence against them and their families, offenses spanning a range of brutality from arbitrary detention, to torture, rape and extrajudicial killing. Samantar was allegedly aware of the crimes being perpetrated against civilians and yet failed to stop them. The suit was dismissed by a federal district court and then reinstated by the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. It is now pending before the Supreme Court, where a peculiar coalition of defenders is urging reversal. Among them, to the confusion of some observers, are five prominent pro-Israel organizations, each with a professed interest in keeping Samantar out of court. In joint amicus briefs, the groups insist that as a former government official, Samantar should be immune from suit. To hold otherwise, they warn, would violate international law and set an inviting precedent for Israel’s enemies and their supporters in the human rights community. The story of Binyam Mohamed is probably one of the most under-reported stories of the war on terrorism — it has still only partially been told. If, as the former Guantanamo prisoner alleges, he had his genitals sliced with a scalpel after being captured by the US, then the defenders of so-called “harsh interrogation techniques” should finally be rendered mute and duly shamed.

The story of Binyam Mohamed is probably one of the most under-reported stories of the war on terrorism — it has still only partially been told. If, as the former Guantanamo prisoner alleges, he had his genitals sliced with a scalpel after being captured by the US, then the defenders of so-called “harsh interrogation techniques” should finally be rendered mute and duly shamed.