Lila MacLellan writes: In New York or L.A., it’s pretty common to learn that a yoga teacher used to be a dancer, an actor, or even a former Wall Street banker. In Bogota and Medellin, the same is true. Except that here, the teacher may also be an ex-member of a Colombian death squad.

Since 2010, a local organization called Dunna: Alternativas Creativas Para la Paz (Dunna: Creative Alternatives for Peace) has been gradually introducing the basic poses to two groups for whom yoga has been a foreign concept: the poor, mostly rural victims of Colombia’s brutal, half-century conflict, and the guerilla fighters who once terrorized them.

Hundreds of ex-militants have already taken the offered yoga courses. A dozen now plan to teach yoga to others.

To stay calm, yoga-teacher-in-training Edifrando Valderrama Holguin turns off the television whenever he sees news broadcasts about young people being recruited into terror groups like ISIL. Valderrama was 12 when he was recruited into the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). He was given a gun, basic training and a heavy dose of leftist ideology. “In the mountains, if I saw someone who was not part of our group, I had to kill him,” he says. “If I had questioned the ideology of the FARC, they would have called me an infiltrator and killed me.”

Now 28, Valderrama lives in the city of Medellin. He works afternoon shifts for a supplier to one of Colombia’s major meat companies, and practices yoga at home in the mornings. Until the program stopped last year, he attended Dunna’s yoga classes, rolling out his mat with former members of both the FARC and Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) — a paramilitary army he once fought against. Although initially surprised that he could feel so much peace lying in corpse pose, Valderrama now hopes to become a yoga teacher, so that he can introduce the healing asanas to ex-militants in Colombia, or even overseas.

Samuel Urueña Lievano, 46, was raped and then recruited into the rival AUC by a relative when he was 15. “They used my anger and hatred to get me to join. I have so much remorse for the things I did during that period,” he tells me as he begins to cry.

Urueña, now a law student in Bogota, takes medications to manage his anxiety and still has nightmares. He calls yoga his closest friend. Practicing the poses every day for two hours has made it possible for him to handle occasional feelings of panic, impatience and frustration, he says. “It has helped me identify who I am. It has given me myself back.” [Continue reading…]

Category Archives: Creativity

Music permeates our brain

Jonathan Berger writes: Neurological research has shown that vivid musical hallucinations are more than metaphorical. They don’t just feel real, they are, from a cognitive perspective, entirely real. In the absence of sound waves, brain activation is strikingly similar to that triggered by external auditory sounds. Why should that be?

Music, repetitive and patterned by nature, provides structure within which we find anchors, context, and a basis for organizing time. In the prehistory of civilization, humans likely found comfort in the audible patterns and structures that accompanied their circadian rhythms — from the coo of a morning dove to the nocturnal chirps of crickets. With the evolution of music a more malleable framework for segmenting and structuring time developed. Humans generated predictable and replicable temporal patterns by drumming, vocalizing, blowing, and plucking. This metered, temporal framework provides an internal world in which we construct predictions about the future — what will happen next, and when it will happen.

This process spotlights the brain itself. The composer Karlheinz Stockhausen hyphenated the term for his craft to underscore the literal meaning of “com-pose” — to put together elements, from com (“with” or “together”) and pose (“put” or “place”). When we imagine music, we literally compose — sometimes recognizable tunes, other times novel combinations of patterns and musical ideas. Toddlers sing themselves to sleep with vocalizations of musical snippets they are conjuring up in their imagination. Typically, these “spontaneous melodies,” as they are referred to by child psychologists, comprise fragments of salient features of multiple songs that the baby is piecing together. In short, we do not merely retrieve music that we store in memory. Rather, a supremely complex web of associations can be stirred and generated as we compose music in our minds.

Today, amid widely disseminated music, we are barraged by a cacophony of disparate musical patterns — more often than not uninvited and unwanted — and likely spend more time than ever obsessing over imagined musical fragments. The brain is a composer whose music orchestrates our lives. And right now the brain is working overtime. [Continue reading…]

Writers around the world feel censored by surveillance

The New York Times reports: A survey of writers around the world by the PEN American Center has found that a significant majority said they were deeply concerned with government surveillance, with many reporting that they have avoided, or have considered avoiding, controversial topics in their work or in personal communications as a result.

The findings show that writers consider freedom of expression to be under significant threat around the world in democratic and nondemocratic countries. Some 75 percent of respondents in countries classified as “free,” 84 percent in “partly free” countries, and 80 percent in countries that were “not free” said that they were “very” or “somewhat” worried about government surveillance in their countries.

The survey, which will be released Monday, was conducted anonymously online in fall 2014 and yielded 772 responses from fiction and nonfiction writers and related professionals, including translators and editors, in 50 countries.

Smaller numbers said they avoided or considered avoiding writing or speaking on certain subjects, with 34 percent in countries classified as free, 44 percent in partly free countries and 61 percent in not free countries reporting self-censorship. Respondents in similar percentages reported curtailing social media activity, or said they were considering it, because of surveillance. [Continue reading…]

An integrated model of creativity and personality

Scott Barry Kaufman writes: Psychologists Guillaume Furst, Paolo Ghisletta and Todd Lubart present an integrative model of creativity and personality that is deeply grounded in past research on the personality of creative people.

Bringing together lots of different research threads over the years, they identified three “super-factors” of personality that predict creativity: Plasticity, Divergence, and Convergence.

Plasticity consists of the personality traits openness to experience, extraversion, high energy, and inspiration. The common factor here is high drive for exploration, and those high in this super-factor of personality tend to have a lot of dopamine — “the neuromodulator of exploration” — coursing through their brains. Prior research has shown a strong link between Plasticity and creativity, especially in the arts.

Divergence consists of non-conformity, impulsivity, low agreeableness, and low conscientiousness. People high in divergence may seem like jerks, but they are often just very independent thinkers. This super-factor is close to Hans Eysenck’s concept of “Psychoticism.” Throughout his life, Eysenck argued that these non-conforming characteristics were important contributors to high creative achievements.

Finally, Convergence consists of high conscientiousness, precision, persistence, and critical sense. While not typically included in discussions of creativity, these characteristics are also important contributors to the creative process. [Continue reading…]

The thoughts of our ancient ancestors

The discovery of what appear to have been deliberately etched markings made by a human ancestor, Homo erectus, on the surface of a shell, call for a reconsideration of assumptions that have been made about the origins of abstract thought.

While the meaning of these zigzag markings will most likely remain forever unknown, it can reasonably be inferred that for the individual who created them, the marks had some significance.

In a report in Nature, Josephine Joordens, a biologist at Leiden University whose team discovered the markings, says:

“We’ve looked at all possibilities, but in the end we are really certain that this must have been made by an agent who did a very deliberate action with a very sharp implement,” says Joordens. Her team tried replicating the pattern on fresh and fossilized shells, “and that made us realize how difficult it really was”, she says.

Saying much more about the engraving is tricky. “If you don’t know the intention of the person who made it, it’s impossible to call it art,” says Joordens.

“But on the other hand, it is an ancient drawing. It is a way of expressing yourself. What was meant by the person who did this, we simply don’t know, ” she adds. “It could have been to impress his girlfriend, or to doodle a bit, or to mark the shell as his own property.”

Clive Finlayson, a zoologist at the Gibraltar Museum who was part of the team that described cross-hatch patterns linked to Neanderthals, is also agnostic about whether to call the H. erectus doodles art. What is more important, he says, is the growing realization that abilities such as abstract thinking, once ascribed to only H. sapiens, were present in other archaic humans, including, now, their ancestors.

“I’ve been suggesting increasingly strongly that a lot of these things that are meant to be modern human we’re finding in other hominids,” he says. “We really need to revisit these concepts and take stock.”

Palaeoanthropology, by necessity, is a highly speculative discipline — therein lies both its strength and its weakness.

The conservatism of hard science recoils at the idea that some scratches on a single shell amount to sufficient evidence to prompt a reconsideration about the origins of the human mind, and yet to refrain from such speculation seems like an effort to restrain the powers of the very thing we are trying to understand.

Rationally, there is as much reason to assume that abstract thinking long predates modern humans and thus searching for evidence of its absence and finding none would leave us agnostic about its presence or absence, than there is reason to assume that at some juncture it was born.

My inclination is to believe that any living creature that has some capacity to construct a neurological representation of their surroundings is by that very capacity employing something akin to abstract thinking.

This ability for the inner to mirror the outer has no doubt evolved, becoming progressively more complex and more deeply abstract, and yet mind, if defined as world-mirroring, seems to have been born when life first moved.

How broken sleep can unleash creativity

Karen Emslie writes: It is 4.18am. In the fireplace, where logs burned, there are now orange lumps that will soon be ash. Orion the Hunter is above the hill. Taurus, a sparkling V, is directly overhead, pointing to the Seven Sisters. Sirius, one of Orion’s heel dogs, is pumping red-blue-violet, like a galactic disco ball. As the night moves on, the old dog will set into the hill.

It is 4.18am and I am awake. Such early waking is often viewed as a disorder, a glitch in the body’s natural rhythm – a sign of depression or anxiety. It is true that when I wake at 4am I have a whirring mind. And, even though I am a happy person, if I lie in the dark my thoughts veer towards worry. I have found it better to get up than to lie in bed teetering on the edge of nocturnal lunacy.

If I write in these small hours, black thoughts become clear and colourful. They form themselves into words and sentences, hook one to the next – like elephants walking trunk to tail. My brain works differently at this time of night; I can only write, I cannot edit. I can only add, I cannot take away. I need my day-brain for finesse. I will work for several hours and then go back to bed.

All humans, animals, insects and birds have clocks inside, biological devices controlled by genes, proteins and molecular cascades. These inner clocks are connected to the ceaseless yet varying cycle of light and dark caused by the rotation and tilt of our planet. They drive primal physiological, neural and behavioural systems according to a roughly 24-hour cycle, otherwise known as our circadian rhythm, affecting our moods, desires, appetites, sleep patterns, and sense of the passage of time.

The Romans, Greeks and Incas woke up without iPhone alarms or digital radio clocks. Nature was their timekeeper: the rise of the sun, the dawn chorus, the needs of the field or livestock. Sundials and hourglasses recorded the passage of time until the 14th century when the first mechanical clocks were erected on churches and monasteries. By the 1800s, mechanical timepieces were widely worn on neck chains, wrists or lapels; appointments could be made and meal- or bed-times set.

Societies built around industrialisation and clock-time brought with them urgency and the concept of being ‘on time’ or having ‘wasted time’. Clock-time became increasingly out of synch with natural time, yet light and dark still dictated our working day and social structures.

Then, in the late 19th century, everything changed. [Continue reading…]

Cognitive disinhibition: the kernel of genius and madness

Dean Keith Simonton writes: When John Forbes Nash, the Nobel Prize-winning mathematician, schizophrenic, and paranoid delusional, was asked how he could believe that space aliens had recruited him to save the world, he gave a simple response. “Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously.”

Nash is hardly the only so-called mad genius in history. Suicide victims like painters Vincent Van Gogh and Mark Rothko, novelists Virginia Woolf and Ernest Hemingway, and poets Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath all offer prime examples. Even ignoring those great creators who did not kill themselves in a fit of deep depression, it remains easy to list persons who endured well-documented psychopathology, including the composer Robert Schumann, the poet Emily Dickinson, and Nash. Creative geniuses who have succumbed to alcoholism or other addictions are also legion.

Instances such as these have led many to suppose that creativity and psychopathology are intimately related. Indeed, the notion that creative genius might have some touch of madness goes back to Plato and Aristotle. But some recent psychologists argue that the whole idea is a pure hoax. After all, it is certainly no problem to come up with the names of creative geniuses who seem to have displayed no signs or symptoms of mental illness.

Opponents of the mad genius idea can also point to two solid facts. First, the number of creative geniuses in the entire history of human civilization is very large. Thus, even if these people were actually less prone to psychopathology than the average person, the number with mental illness could still be extremely large. Second, the permanent inhabitants of mental asylums do not usually produce creative masterworks. The closest exception that anyone might imagine is the notorious Marquis de Sade. Even in his case, his greatest (or rather most sadistic) works were written while he was imprisoned as a criminal rather than institutionalized as a lunatic.

So should we believe that creative genius is connected with madness or not? Modern empirical research suggests that we should because it has pinpointed the connection between madness and creativity clearly. The most important process underlying strokes of creative genius is cognitive disinhibition — the tendency to pay attention to things that normally should be ignored or filtered out by attention because they appear irrelevant. [Continue reading…]

35,000 year-old Indonesian cave paintings suggest art came out of Africa

The Guardian reports: Paintings of wild animals and hand markings left by adults and children on cave walls in Indonesia are at least 35,000 years old, making them some of the oldest artworks known.

The rock art was originally discovered in caves on the island of Sulawesi in the 1950s, but dismissed as younger than 10,000 years old because scientists thought older paintings could not possibly survive in a tropical climate.

But fresh analysis of the pictures by an Australian-Indonesian team has stunned researchers by dating one hand marking to at least 39,900 years old, and two paintings of animals, a pig-deer or babirusa, and another animal, probably a wild pig, to at least 35,400 and 35,700 years ago respectively.

The work reveals that rather than Europe being at the heart of an explosion of creative brilliance when modern humans arrived from Africa, the early settlers of Asia were creating their own artworks at the same time or even earlier.

Archaeologists have not ruled out that the different groups of colonising humans developed their artistic skills independently of one another, but an enticing alternative is that the modern human ancestors of both were artists before they left the African continent.

“Our discovery on Sulawesi shows that cave art was made at opposite ends of the Pleistocene Eurasian world at about the same time, suggesting these practices have deeper origins, perhaps in Africa before our species left this continent and spread across the globe,” said Dr Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist at the University of Wollongong. [Continue reading…]

The way we live our lives in stories

Jonathan Gottschall: There’s a big question about what it is that makes people people. What is it that most sets our species apart from every other species? That’s the debate that I’ve been involved in lately.

When we call the species homo sapiens that’s an argument in the debate. It’s an argument that it is our sapience, our wisdom, our intelligence, or our big brains that most sets our species apart. Other scientists, other philosophers have pointed out that, no, a lot of the time we’re really not behaving all that rationally and reasonably. It’s our upright posture that sets us apart, or it’s our opposable thumb that allows us to do this incredible tool use, or it’s our cultural sophistication, or it’s the sophistication of language, and so on and so forth. I’m not arguing against any of those things, I’m just arguing that one thing of equal stature has typically been left off of this list, and that’s the way that people live their lives inside stories.

We live in stories all day long—fiction stories, novels, TV shows, films, interactive video games. We daydream in stories all day long. Estimates suggest we just do this for hours and hours per day — making up these little fantasies in our heads, these little fictions in our heads. We go to sleep at night to rest; the body rests, but not the brain. The brain stays up at night. What is it doing? It’s telling itself stories for about two hours per night. It’s eight or ten years out of our lifetime composing these little vivid stories in the theaters of our minds.

I’m not here to downplay any of those other entries into the “what makes us special” sweepstakes. I’m just here to say that one thing that has been left off the list is storytelling. We live our lives in stories, and it’s sort of mysterious that we do this. We’re not really sure why we do this. It’s one of these questions — storytelling — that falls in the gap between the sciences and the humanities. If you have this division into two cultures: you have the science people over here in their buildings, and the humanities people over here in their buildings. They’re writing in their own journals, and publishing their own book series, and the scientists are doing the same thing.

You have this division, and you have all this area in between the sciences and the humanities that no one is colonizing. There are all these questions in the borderlands between these disciplines that are rich and relatively unexplored. One of them is storytelling and it’s one of these questions that humanities people aren’t going to be able to figure out on their own because they don’t have a scientific toolkit that will help them gradually, painstakingly narrow down the field of competing ideas. The science people don’t really see these questions about storytelling as in their jurisdiction: “This belongs to someone else, this is the humanities’ territory, we don’t know anything about it.”

What is needed is fusion — people bringing together methods, ideas, approaches from scholarship and from the sciences to try to answer some of these questions about storytelling. Humans are addicted to stories, and they play an enormous role in human life and yet we know very, very little about this subject. [Continue reading… or watch a video of Gottschall’s talk.]

Cynicism is toxic

Cynics fool themselves by thinking they can’t be fooled.

The cynic imagines he’s guarding himself against being duped. He’s not naive, he’s worldly wise, so he’s not about to get taken in — but this psychic insulation comes at a price.

The cynic is cautious and mistrustful. Worst of all, the cynic by relying too much on his own counsel, saps the foundation of curiosity, which is the ability to be surprised.

While the ability to develop and sustain an open mind has obvious psychological value, neurologists now say that it’s also necessary for the health of the brain. Cynicism leads towards dementia.

One of the researchers in a new study suggests that the latest findings may offer insights on how to reduce the risks of dementia, yet that seems to imply that people might be less inclined to become cynical simply by knowing that its bad for their health. How are we to reduce the risks of becoming cynical in the first place?

One of the most disturbing findings of a recent Pew Research Center survey, Millenials in Adulthood, was this:

In response to a long-standing social science survey question, “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people,” just 19% of Millennials say most people can be trusted, compared with 31% of Gen Xers, 37% of Silents and 40% of Boomers.

While this trust deficit among Millennials no doubt has multiple causes, such as the socially fragmented nature of our digital world, I don’t believe that there has ever before been a generation so thoroughly trained in fear. Beneath cynicism lurks fear.

The fear may have calmed greatly since the days of post-9/11 hysteria, yet it has not gone away. It’s the background noise of American life. It might no longer be focused so strongly on terrorism, since there are plenty of other reasons to fear — some baseless, some over-stated, and some underestimated. But the aggregation of all these fears produces a pervasive mistrust of life.

ScienceDaily: People with high levels of cynical distrust may be more likely to develop dementia, according to a study published in the May 28, 2014, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

Cynical distrust, which is defined as the belief that others are mainly motivated by selfish concerns, has been associated with other health problems, such as heart disease. This is the first study to look at the relationship between cynicism and dementia.

“These results add to the evidence that people’s view on life and personality may have an impact on their health,” said study author Anna-Maija Tolppanen, PhD, of the University of Eastern Finland in Kuopio. “Understanding how a personality trait like cynicism affects risk for dementia might provide us with important insights on how to reduce risks for dementia.”

For the study, 1,449 people with an average age of 71 were given tests for dementia and a questionnaire to measure their level of cynicism. The questionnaire has been shown to be reliable, and people’s scores tend to remain stable over periods of several years. People are asked how much they agree with statements such as “I think most people would lie to get ahead,” “It is safer to trust nobody” and “Most people will use somewhat unfair reasons to gain profit or an advantage rather than lose it.” Based on their scores, participants were grouped in low, moderate and high levels of cynical distrust.

A total of 622 people completed two tests for dementia, with the last one an average of eight years after the study started. During that time, 46 people were diagnosed with dementia. Once researchers adjusted for other factors that could affect dementia risk, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol and smoking, people with high levels of cynical distrust were three times more likely to develop dementia than people with low levels of cynicism. Of the 164 people with high levels of cynicism, 14 people developed dementia, compared to nine of the 212 people with low levels of cynicism.

The study also looked at whether people with high levels of cynicism were more likely to die sooner than people with low levels of cynicism. A total of 1,146 people were included in this part of the analysis, and 361 people died during the average of 10 years of follow-up. High cynicism was initially associated with earlier death, but after researchers accounted for factors such as socioeconomic status, behaviors such as smoking and health status, there was no longer any link between cynicism and earlier death.

Stories made present

Richard Hamilton writes: My first job was as a lawyer. I was not a very happy or inspired lawyer. One night I was driving home listening to a radio report, and there is something very intimate about radio: a voice comes out of a machine and into the listener’s ear. With rain pounding the windscreen and only the dashboard lights and the stereo for company, I thought to myself, ‘This is what I want to do.’ So I became a radio journalist.

As broadcasters, we are told to imagine speaking to just one person. My tutor at journalism college told me that there is nothing as captivating as the human voice saying something of interest (he added that radio is better than TV because it has the best pictures). We remember where we were when we heard a particular story. Even now when I drive in my car, the memory of a scene from a radio play can be ignited by a bend in a country road or a set of traffic lights in the city.

But potent as radio seems, can a recording device ever fully replicate the experience of listening to a live storyteller? The folklorist Joseph Bruchac thinks not. ‘The presence of teller and audience, and the immediacy of the moment, are not fully captured by any form of technology,’ he wrote in a comment piece for The Guardian in 2010. ‘Unlike the insect frozen in amber, a told story is alive… The story breathes with the teller’s breath.’ And as devoted as I am to radio, my recent research into oral storytelling makes me think that Bruchac may be right. [Continue reading…]

Google’s bold and deceptive Partition ad campaign

People think of Google, Apple, Coca-Cola and so forth as brands, but these names are better thought of as branding irons designed to leave an indelible imprint on their customers’ brains. We are the cattle and even though the branding process is seemingly anodyne — generally producing pleasure rather than pain — when branding “works” it yields a form of ownership. Except unlike livestock which have no loyalty to their owners, we allow ourselves to be corralled and tethered with no visible restraint. We have become the most successfully domesticated of animals.

Advertising is all about short-circuiting reason and misappropriating emotion in the service of a commercial goal. It aims to sear a brand onto the brain in conjunction with a positive feeling, so that the brand on its own can later trigger the same feeling.

The Partition of British India in 1947 resulting in the creation of the republics of India and Pakistan involved the displacement of 14 million people and the deaths of as many as one million. Many of the wounds have still not healed after the subcontinent was ripped apart. But here comes Google with an ad called ‘Reunion’, offering a balm in the form of a touching short story.

“I don’t work on a computer and I have no idea what Google is. But I am glad to be a part of what I thought was a very sentimental story,” said M.S. Sathyu, who plays “Yusuf”, an elderly sweet seller in Lahore who features in the advertisement.

The Indian Express reports:

The three-and-half minute ad was shot in different areas in Delhi, including an old haveli in Connaught Place, Red Fort, India Gate and a small scene in Lahore, Pakistan. “We have all heard stories about Partition and how friends and families were separated. So the background for the ad was set. But we wanted to make sure we did not adhere to clichés,” says Mumbai-based Amit Sharma of Chrome Pictures who directed the commercial.

As the ad begins we see an 80-something-year Baldev (VM Badola) in his small store in Delhi narrate the stories of his childhood to his granddaughter Suman (Auritra Ghosh). He reminiscences about times with his best friend, Yusuf (MS Sathyu), flying kites in a park in Lahore and stealing jhajariyas from Yusuf’s Fazal Sweet shop. This sends the granddaughter on an online search until she speaks to Yusuf himself. And on her grandfather’s birthday, she arranges a reunion between Yusuf and Baldev.

Google offered its advertising agency broad latitude in crafting a message:

The scriptwriter for the ad, Sukesh Kumar Nayak of Ogilvy and Mather, says that he was pleasantly surprised when a tech giant like Google specified in their brief that the only thing they wanted was to see was how meaningful the search engine is in real life. “Our entire life revolves around Google, it is our instant response to something we don’t know. But we wanted to dig deeper, and make the connection between real life and Google, magical,” says Nayak.

Or to put it another way, to contrive a connection between real life and fantasy, since as Hamna Zubair points out, the barriers between India and Pakistan are far more extensive than any that can be bridged by Google.

It is notoriously hard for an Indian national to get a visa to Pakistan and vice versa. In fact, as little as five years ago, after the Mumbai bombings, it was near impossible. A series of false starts, misunderstandings, and in some cases, outright armed conflicts have plagued the neighbors ever since they came into existence in 1947.

Whereas an American citizen, for example, can get a visa to India that is valid for 5 or even 10 years without much fuss, a Pakistani citizen has to fill out a “Special Pakistan Application” and get an Indian national living in India to write him or her a letter of sponsorship. Even then, a visa isn’t guaranteed, and your passport could be held for many months as you’re screened. Indian citizens who want to visit Pakistan don’t have it much easier.

For the many, many Indians and Pakistanis who have families across the border and want to visit them, this is a constant source of grief. We all wish it were easier to traverse the India-Pakistan border, but this is not the case, and never has been.

So while Google’s ad does tap into a desire many Pakistanis and Indians have – that is, to end long-standing political conflict and just visit a land their ancestors lived on – it isn’t an accurate representation of reality. At best, one hopes this ad may generate a greater push to relax visa restrictions. Until then, however, just like India and Pakistan posture about making peace, one has to wonder if Google isn’t indulging a little fantasy as well.

Ironically, a real life connection that Google hopes its audience must have forgotten was evident in the Mumbai attacks themselves in which the terrorists used Google Earth to locate their targets.

If Google was really making this a better world, the more reliable evidence of that might be seen in search trends — not feel-good commercials.

What are the hottest searches right now? Indians are preoccupied with the departure of cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, while Americans focus on the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Still, since a commercial like Reunion conveys such a positive sentiment, can’t it at least be viewed as harmless? And might it not provide a useful if small nudge in the direction of India-Pakistan reconciliation?

Those who define the strategic interests of each state have much more interest in shaping rather than being shaped by public opinion. Moreover, the resolution of conflicts such as the one that centers on Kashmir hinges on much more than a desire among people to get along and reconnect. Google has no interest in changing the political landscape; it simply wants to expand its market share.

Aside from the fact that a commercial likes this conveniently ignores the messiness of politics, the more pernicious effect of advertising in general is cultural.

The talent of storytellers and artists is being wasted in advertising agencies where creativity is employed to strengthen the bottom line — not expand the imagination.

Even worse, metaphor — the means through which the human mind can most evocatively and directly perceive connections — has been corrupted because above all, advertising trades in the promotion of false connections through its cynical use of metaphorical imagery. Advertising always promises more than the product; it equates the product with a better life.

Just as Coca-Cola once promised to create a world in perfect harmony, now Google promises to bring together long lost friends.

Both are seductive lies and we gladly yield to the manipulation — acting as though our exposure to such a ceaseless torrent of commercial lies will have no detrimental impact on the way we think.

Master of many trades

Robert Twigger writes: I travelled with Bedouin in the Western Desert of Egypt. When we got a puncture, they used tape and an old inner tube to suck air from three tyres to inflate a fourth. It was the cook who suggested the idea; maybe he was used to making food designed for a few go further. Far from expressing shame at having no pump, they told me that carrying too many tools is the sign of a weak man; it makes him lazy. The real master has no tools at all, only a limitless capacity to improvise with what is to hand. The more fields of knowledge you cover, the greater your resources for improvisation.

We hear the descriptive words psychopath and sociopath all the time, but here’s a new one: monopath. It means a person with a narrow mind, a one-track brain, a bore, a super-specialist, an expert with no other interests — in other words, the role-model of choice in the Western world. You think I jest? In June, I was invited on the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 to say a few words on the river Nile, because I had a new book about it. The producer called me ‘Dr Twigger’ several times. I was flattered, but I also felt a sense of panic. I have never sought or held a PhD. After the third ‘Dr’, I gently put the producer right. And of course, it was fine — he didn’t especially want me to be a doctor. The culture did. My Nile book was necessarily the work of a generalist. But the radio needs credible guests. It needs an expert — otherwise why would anyone listen?

The monopathic model derives some of its credibility from its success in business. In the late 18th century, Adam Smith (himself an early polymath who wrote not only on economics but also philosophy, astronomy, literature and law) noted that the division of labour was the engine of capitalism. His famous example was the way in which pin-making could be broken down into its component parts, greatly increasing the overall efficiency of the production process. But Smith also observed that ‘mental mutilation’ followed the too-strict division of labour. Or as Alexis de Tocqueville wrote: ‘Nothing tends to materialise man, and to deprive his work of the faintest trace of mind, more than extreme division of labour.’ [Continue reading…]

Star Axis, a masterpiece forty years in the making

Ross Andersen writes: On a hot afternoon in late June, I pulled to the side of a two-lane desert highway in eastern New Mexico, next to a specific mile marker. An hour earlier, a woman had told me to wait for her there at three o’clock, ‘sharp’. I edged as far off the shoulder as I could, to avoid being seen by passing traffic, and parked facing the wilderness. A sprawling, high desert plateau was set out before me, its terrain a maze of raised mesas, sandstone survivors of differential erosion. Beyond the plateau, the landscape stretched for miles, before dissolving into a thin strip of desert shimmer. The blurry line marked the boundary between the land and one of the biggest, bluest skies I’d ever seen.

I had just switched off the ignition when I spotted a station wagon roaring toward me from the plateau, towing a dust cloud that looked like a miniature sandstorm. Its driver was Jill O’Bryan, the wife and gatekeeper of Charles Ross, the renowned sculptor. Ross got his start in the Bay Area art world of the mid‑1960s, before moving to New York, where he helped found one of SoHo’s first artist co-ops. In the early 1970s, he began spending a lot of time here in the New Mexico desert. He had acquired a remote patch of land, a mesa he was slowly transforming into a massive work of land art, a naked-eye observatory called Star Axis. Ross rarely gives interviews about Star Axis, but when he does he describes it as a ‘perceptual instrument’. He says it is meant to offer an ‘intimate experience’ of how ‘the Earth’s environment extends into the space of the stars’. He has been working on it for more than 40 years, but still isn’t finished.

I knew Star Axis was out there on the plateau somewhere, but I didn’t know where. Its location is a closely guarded secret. Ross intends to keep it that way until construction is complete, but now that he’s finally in the homestretch he has started letting in a trickle of visitors. I knew, going in, that a few Hollywood celebrities had been out to Star Axis, and that Ross had personally showed it to Stewart Brand. After a few months of emails, and some pleading on my part, he had agreed to let me stay overnight in it.

Once O’Bryan was satisfied that I was who I said I was, she told me to follow her, away from the highway and into the desert. I hopped back into my car, and we caravanned down a dirt road, bouncing and churning up dust until, 30 minutes in, O’Bryan suddenly slowed and stuck her arm out her driver’s side window. She pointed toward a peculiar looking mesa in the distance, one that stood higher than the others around it. Notched into the centre of its roof was a granite pyramid, a structure whose symbolic power is as old as history.

Twenty minutes later, O’Bryan and I were parked on top of the mesa, right at the foot of the pyramid and she was giving me instructions. ‘Don’t take pictures,’ she said, ‘and please be vague about the location in your story.’ She also told me not to use headlights on the mesa top at night, lest their glow tip off unwanted visitors. There are artistic reasons for these cloak-and-dagger rituals. Like any ambitious artist, Ross wants to polish and perfect his opus before unveiling it. But there are practical reasons, too. For while Star Axis itself is nearly built, its safety features are not, and at night the pitch black of this place can disorient you, sending you stumbling into one of its chasms. There is even an internet rumour — Ross wouldn’t confirm it — that the actress Charlize Theron nearly fell to her death here. [Continue reading…]

Video — Ken Robinson: The element — where natural talent meets personal passion

Want to learn how to think? Read fiction

Pacific Standard: Are you uncomfortable with ambiguity? It’s a common condition, but a highly problematic one. The compulsion to quell that unease can inspire snap judgments, rigid thinking, and bad decision-making.

Fortunately, new research suggests a simple antidote for this affliction: Read more literary fiction.

A trio of University of Toronto scholars, led by psychologist Maja Djikic, report that people who have just read a short story have less need for what psychologists call “cognitive closure.” Compared with peers who have just read an essay, they expressed more comfort with disorder and uncertainty — attitudes that allow for both sophisticated thinking and greater creativity.

“Exposure to literature,” the researchers write in the Creativity Research Journal, “may offer a (way for people) to become more likely to open their minds.”

Djikic and her colleagues describe an experiment featuring 100 University of Toronto students. After arriving at the lab and providing some personal information, the students read either one of eight short stories or one of eight essays. The fictional stories were by authors including Wallace Stegner, Jean Stafford, and Paul Bowles; the non-fiction essays were by equally illustrious writers such as George Bernard Shaw and Stephen Jay Gould. [Continue reading…]

How science devalues non-scientific knowledge

Riverside, IL

“Systematic differences in EEG recordings were found between three urban areas in line with restoration theory. This has implications for promoting urban green space as a mood-enhancing environment for walking or for other forms of physical or reflective activity.”

In other words, getting away from a frenetic office and city traffic and taking a walk in a peaceful leafy park is good for you.

The idea that visiting green spaces like parks or tree-filled plazas lessens stress and improves concentration is not new. Researchers have long theorized that green spaces are calming, requiring less of our so-called directed mental attention than busy, urban streets do. Instead, natural settings invoke “soft fascination,” a beguiling term for quiet contemplation, during which directed attention is barely called upon and the brain can reset those overstretched resources and reduce mental fatigue.

But this theory, while agreeable, has been difficult to put to the test. Previous studies have found that people who live near trees and parks have lower levels of cortisol, a stress hormone, in their saliva than those who live primarily amid concrete, and that children with attention deficits tend to concentrate and perform better on cognitive tests after walking through parks or arboretums. More directly, scientists have brought volunteers into a lab, attached electrodes to their heads and shown them photographs of natural or urban scenes, and found that the brain wave readouts show that the volunteers are more calm and meditative when they view the natural scenes.

But it had not been possible to study the brains of people while they were actually outside, moving through the city and the parks. Or it wasn’t, until the recent development of a lightweight, portable version of the electroencephalogram, a technology that studies brain wave patterns.

For the new study, published this month in The British Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh and the University of Edinburgh attached these new, portable EEGs to the scalps of 12 healthy young adults. The electrodes, hidden unobtrusively beneath an ordinary looking fabric cap, sent brain wave readings wirelessly to a laptop carried in a backpack by each volunteer.

The researchers, who had been studying the cognitive impacts of green spaces for some time, then sent each volunteer out on a short walk of about a mile and half that wound through three different sections of Edinburgh.

The first half mile or so took walkers through an older, historic shopping district, with fine, old buildings and plenty of pedestrians on the sidewalk, but only light vehicle traffic.

The walkers then moved onto a path that led through a park-like setting for another half mile.

Finally, they ended their walk strolling through a busy, commercial district, with heavy automobile traffic and concrete buildings.

The walkers had been told to move at their own speed, not to rush or dawdle. Most finished the walk in about 25 minutes.

Throughout that time, the portable EEGs on their heads continued to feed information about brain wave patterns to the laptops they carried.

Afterward, the researchers compared the read-outs, looking for wave patterns that they felt were related to measures of frustration, directed attention (which they called “engagement”), mental arousal and meditativeness or calm.

What they found confirmed the idea that green spaces lessen brain fatigue.

Research of this kind is not worthless. If urban planners are able to win approval for the construction of more parks because they can use findings like these in order to argue that parks have economic and health value to the populations they serve, all well and good.

But we don’t need electronic data or studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals in order to recognize the value of parks. Least of all should we imagine that in the absence of such information we cannot have confidence in making judgements about such matters.

A pernicious effect of studies of the kind described above is that they can lead people to believe that unless one can find scientific evidence to support conclusions about what possesses value in this world, then perceptions, intuitions and convictions will offer no real guidance. They belong to the domain of subjectivity and the contents of the human mind — an arena into which science cannot venture.

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), the father of American landscape architecture, didn’t have access to portable EEGs and for that and other reasons might not have been able to establish scientifically that the parks he designed were good for people. Yet the value they provided didn’t need to be proved through data. The simple testimony of the parks’ visitors was proof enough. Moreover, the principles of design he employed could not be reduced to quantifiable formulae yet they were teachable as an art.

Matt Linderman describes ten lessons from Olmsted’s approach:

1) Respect “the genius of a place.”

Olmsted wanted his designs to stay true to the character of their natural surroundings. He referred to “the genius of a place,” a belief that every site has ecologically and spiritually unique qualities. The goal was to “access this genius” and let it infuse all design decisions.

This meant taking advantage of unique characteristics of a site while also acknowledging disadvantages. For example, he was willing to abandon the rainfall-requiring scenery he loved most for landscapes more appropriate to climates he worked in. That meant a separate landscape style for the South while in the dryer, western parts of the country he used a water-conserving style (seen most visibly on the campus of Stanford University, design shown at right).

2) Subordinate details to the whole.

Olmsted felt that what separated his work from a gardener was “the elegance of design,” (i.e. one should subordinate all elements to the overall design and the effect it is intended to achieve). There was no room for details that were to be viewed as individual elements. He warned against thinking “of trees, of turf, water, rocks, bridges, as things of beauty in themselves.” In his work, they were threads in a larger fabric. That’s why he avoided decorative plantings and structures in favor of a landscapes that appeared organic and true.3) The art is to conceal art.

Olmsted believed the goal wasn’t to make viewers see his work. It was to make them unaware of it. To him, the art was to conceal art. And the way to do this was to remove distractions and demands on the conscious mind. Viewers weren’t supposed to examine or analyze parts of the scene. They were supposed to be unaware of everything that was working.He tried to recreate the beauty he saw in the Isle of Wight during his first trip to England in 1850: “Gradually and silently the charm comes over us; we know not exactly where or how.” Olmsted’s works appear so natural that one critic wrote, “One thinks of them as something not put there by artifice but merely preserved by happenstance.”

4) Aim for the unconscious.

Related to the previous point, Olmsted was a fan of Horace Bushnell’s writings about “unconscious influence” in people. (Bushnell believed real character wasn’t communicated verbally but instead at a level below that of consciousness.) Olmsted applied this idea to his scenery. He wanted his parks to create an unconscious process that produced relaxation. So he constantly removed distractions and demands on the conscious mind. [Continue reading…]

Only a creator culture can save us

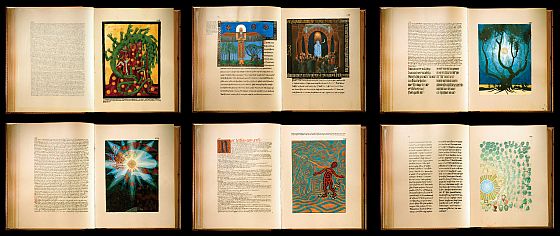

Pages from The Red Book

Damien Walter writes: Between the years of 1914 and 1930 the psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology Carl Gustav Jung undertook what he later termed a ‘voluntary confrontation with his unconscious’. Employing certain techniques of active imagination that became part of his theory of human development, Jung incited visions, dreams and other manifestations of his imagination, which he recorded in writing and pictures. For some years, he kept the results of this process secret, though he described them to close friends and family as the most important work of his life. Late in his career, he set about collecting and transcribing these dreams and visions.

The product was the ‘Liber Novus’ or ‘New Book’, now known simply as The Red Book. Despite requests for access from some of the leading thinkers and intellectuals of the 20th century, very few people outside of Jung’s close family were allowed to see it before its eventual publication in 2009. It has since been recognised as one of the great creative acts of the century, a magnificent and visionary illuminated manuscript equal to the works of William Blake.

It is from his work on The Red Book that all of Jung’s theories on archetypes, individuation and the collective unconscious stem. Of course, Jung is far from alone in esteeming human creativity. The creative capacity is central to the developmental psychology of Jean Piaget and the constructivist theory of learning, and creativity is increasingly at the heart of our models of economic growth and development. But Jung provides the most satisfying explanation I know for why the people I worked with got so much out of discovering their own creativity, and why happiness and the freedom to create are so closely linked.

Jung dedicated his life to understanding human growth, and the importance of creativity to that process. It seems fitting that the intense process that led to the The Red Book should also have been integral to Jung’s own personal development. Already well into his adult life, he had yet to make the conceptual breakthroughs that would become the core of his model of human psychology. In quite a literal sense, the process of creating The Red Book was also the process of creating Carl Jung. This simple idea, that creativity is central to our ongoing growth as human beings, opens up a very distinctive understanding of what it means to make something. [Continue reading…]