One of the strange aspects relating to conspiracy theories concerning 9/11 is that they unwittingly obscure something even worse: that the US government foments terrorism not by design but by neglect; that its policies have had a direct and instrumental role in creating terrorists not simply by providing individuals and groups with an ideological pretext for engaging in terrorism but much more specifically by creating the conditions an individual’s political opposition to America’s actions would shift to unrestrained violent opposition.

The key which often unlocks the terrorist’s capacity for violence is his experience of being subject to violence through torture.

Chris Zambelis writes:

There is ample evidence that a number of prominent militants — including al-Qaeda deputy commander Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri and the late al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi — endured systematic torture at the hands of the Egyptian and Jordanian authorities, respectively. Many observers believe that their turn toward extreme radicalism represented as much an attempt to exact revenge against their tormentors and, by extension, the United States, as it was about fulfilling an ideology. Those who knew Zawahiri and can relate to his experience believe that his behavior today is greatly influenced by his pursuit of personal redemption to compensate for divulging information about his associates after breaking down amid brutal torture sessions during his imprisonment in the early 1980s. For radical Islamists and their sympathizers, U.S. economic, military, and diplomatic support for regimes that engage in this kind of activity against their own citizens vindicates al-Qaeda’s claims of the existence of a U.S.-led plot to attack Muslims and undermine Islam. In al-Qaeda’s view, these circumstances require that Muslims organize and take up arms in self-defense against the United States and its allies in the region.

The latest revelations provided by Wikileaks show how the war in Iraq — the centerpiece of the Bush administration’s war on terrorism — became not simply a terrorist training ground, but a cauldron in which terrorists could be forged.

FRAGO 242: PROVIDED THE INITIAL REPORT CONFIRMS U.S. FORCES WERE NOT INVOLVED IN THE DETAINEE ABUSE, NO FURTHER INVESTIGATION WILL BE CONDUCTED UNLESS DIRECTED BY HHQ. JUNE 26, 2004

The Guardian reports:

A grim picture of the US and Britain’s legacy in Iraq has been revealed in a massive leak of American military documents that detail torture, summary executions and war crimes.

Almost 400,000 secret US army field reports have been passed to the Guardian and a number of other international media organisations via the whistleblowing website WikiLeaks.

The electronic archive is believed to emanate from the same dissident US army intelligence analyst who earlier this year is alleged to have leaked a smaller tranche of 90,000 logs chronicling bloody encounters and civilian killings in the Afghan war.

The new logs detail how:

• US authorities failed to investigate hundreds of reports of abuse, torture, rape and even murder by Iraqi police and soldiers whose conduct appears to be systematic and normally unpunished.

• A US helicopter gunship involved in a notorious Baghdad incident had previously killed Iraqi insurgents after they tried to surrender.

• More than 15,000 civilians died in previously unknown incidents. US and UK officials have insisted that no official record of civilian casualties exists but the logs record 66,081 non-combatant deaths out of a total of 109,000 fatalities.

The Pentagon might hide behind claims that it neither authorized nor condoned violence used by Iraqi authorities on Iraqi detainees, but the difference between being an innocent bystander and being complicit consists in whether one has the power to intervene. The US military’s hands were not tied. As the occupying power it had both the means, the legal authority and the legal responsibility to stop torture in Iraq. It’s failure to do so was a matter of choice.

Will the latest revelations from Wikileaks be of any political consequence? I seriously doubt it, given that we now have a president dedicated not only to refusing to look back but also to perpetuating most of the policies instituted by his predecessor.

For more information on the documents released by Wikileaks, see The Guardian‘s Iraq war logs page.

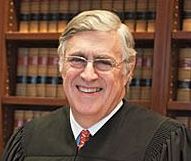

In a landmark case, the first trial of a former Guantánamo detainee, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan of United States District Court in Manhattan

In a landmark case, the first trial of a former Guantánamo detainee, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan of United States District Court in Manhattan  The State website usefully provides a map, just in case anyone isn’t sure where Europe is. Should Americans already there jump on the first plane to head home? Apparently not.

The State website usefully provides a map, just in case anyone isn’t sure where Europe is. Should Americans already there jump on the first plane to head home? Apparently not.

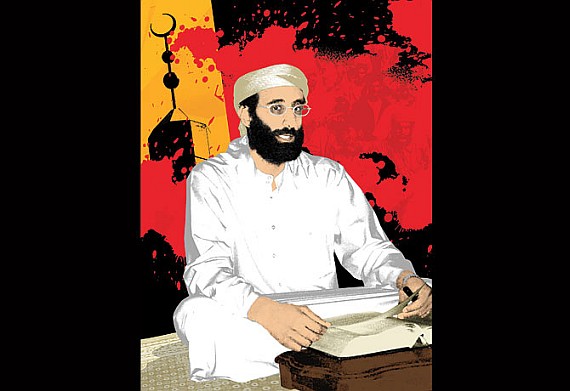

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target.

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target. In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of

In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of