Every year, the images of a national security state careening out of control, as depicted in Terry Gilliam’s 1985 movie Brazil, become eerily more realistic. In his Ministry of Information, the underlings sneak their entertainment when the overseer steps out of sight, but at the National Counterterrorism Center (a “dumping ground for bad analysts“), entertainment (otherwise known as cable news) is on constant big-screen display.

The Washington Post‘s investigation into “Top Secret America” reveals two sadly predictable tendencies:

1. That the default position inside the US government remains: any problem can be solved if enough money is thrown at it, and

2. the primary responsibility of an investigative reporter dealing with a story like this is supposedly to focus on whether taxpayers’ money is being well-spent and making us safer.

The first feature article in the series says:

At least 20 percent of the government organizations that exist to fend off terrorist threats were established or refashioned in the wake of 9/11. Many that existed before the attacks grew to historic proportions as the Bush administration and Congress gave agencies more money than they were capable of responsibly spending.

The Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency, for example, has gone from 7,500 employees in 2002 to 16,500 today. The budget of the National Security Agency, which conducts electronic eavesdropping, doubled. Thirty-five FBI Joint Terrorism Task Forces became 106. It was phenomenal growth that began almost as soon as the Sept. 11 attacks ended.

Nine days after the attacks, Congress committed $40 billion beyond what was in the federal budget to fortify domestic defenses and to launch a global offensive against al-Qaeda. It followed that up with an additional $36.5 billion in 2002 and $44 billion in 2003. That was only a beginning.

With the quick infusion of money, military and intelligence agencies multiplied. Twenty-four organizations were created by the end of 2001, including the Office of Homeland Security and the Foreign Terrorist Asset Tracking Task Force. In 2002, 37 more were created to track weapons of mass destruction, collect threat tips and coordinate the new focus on counterterrorism. That was followed the next year by 36 new organizations; and 26 after that; and 31 more; and 32 more; and 20 or more each in 2007, 2008 and 2009.

In all, at least 263 organizations have been created or reorganized as a response to 9/11. Each has required more people, and those people have required more administrative and logistic support: phone operators, secretaries, librarians, architects, carpenters, construction workers, air-conditioning mechanics and, because of where they work, even janitors with top-secret clearances.

The report continues:

Not far from the Dulles Toll Road, the CIA has expanded into two buildings that will increase the agency’s office space by one-third. To the south, Springfield is becoming home to the new $1.8 billion National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency headquarters, which will be the fourth-largest federal building in the area and home to 8,500 employees. Economic stimulus money is paying hundreds of millions of dollars for this kind of federal construction across the region.

It’s not only the number of buildings that suggests the size and cost of this expansion, it’s also what is inside: banks of television monitors. “Escort-required” badges. X-ray machines and lockers to store cellphones and pagers. Keypad door locks that open special rooms encased in metal or permanent dry wall, impenetrable to eavesdropping tools and protected by alarms and a security force capable of responding within 15 minutes. Every one of these buildings has at least one of these rooms, known as a SCIF, for sensitive compartmented information facility. Some are as small as a closet; others are four times the size of a football field.

SCIF size has become a measure of status in Top Secret America, or at least in the Washington region of it. “In D.C., everyone talks SCIF, SCIF, SCIF,” said Bruce Paquin, who moved to Florida from the Washington region several years ago to start a SCIF construction business. “They’ve got the penis envy thing going. You can’t be a big boy unless you’re a three-letter agency and you have a big SCIF.”

SCIFs are not the only must-have items people pay attention to. Command centers, internal television networks, video walls, armored SUVs and personal security guards have also become the bling of national security.

“You can’t find a four-star general without a security detail,” said one three-star general now posted in Washington after years abroad. “Fear has caused everyone to have stuff. Then comes, ‘If he has one, then I have to have one.’ It’s become a status symbol.”

Among the most important people inside the SCIFs are the low-paid employees carrying their lunches to work to save money. They are the analysts, the 20- and 30-year-olds making $41,000 to $65,000 a year, whose job is at the core of everything Top Secret America tries to do.

At its best, analysis melds cultural understanding with snippets of conversations, coded dialogue, anonymous tips, even scraps of trash, turning them into clues that lead to individuals and groups trying to harm the United States.

Their work is greatly enhanced by computers that sort through and categorize data. But in the end, analysis requires human judgment, and half the analysts are relatively inexperienced, having been hired in the past several years, said a senior ODNI official. Contract analysts are often straight out of college and trained at corporate headquarters.

Nine years after the 9/11 attacks, the United States has a bloated national security structure of questionable effectiveness, at fantastic cost, and with very little accountability. Yet the analysis implies that if the system was more efficient and could indeed deliver as promised by making America safer, then this would indeed be a good thing.

But do we need to be safer or simply less afraid?

The explosion in the growth of the national security economy occurred right at the moment that the technology industry was desperate for support. The internet bubble had burst, an IPO no longer offered a path to quick fortunes for companies that had yet to develop an effective business model, so if the stock market was no longer willing to throw mountains of cash at speculative technological innovation, in the post 9/11 economy, the US government quickly became the investor of choice — at least for companies that could make a halfway plausible claim that their niche expertise might in some way enhance US national security.

If greed was the engine of economic growth of the 90s, fear has demonstrated its economic value for most of the last decade. But what neither greed nor fear do is to improve the quality of life. That only happens when we look at the ways our lives are impoverished and address those needs.

The need to feel safer is a need that has in large part been manufactured by those eager to capitalize on the economic value of fear.

Just suppose that after 9/11 George Bush’s response had been this: clean up the mess in New York and Washington, improve security on airlines so no one could hijack a plane with a pocket knife, and then be done with it. Would we not now be living in a much better world?

Perhaps we should be less afraid of those who might attack us than those who are in the business of protecting us. Top secret America looks like the biggest protection racket ever created.

“Jewish terrorists have just blown up the King David Hotel!” This short message was received by the London Bureau of United Press International (UPI) shortly after noon, Palestine time. It was signed by a UPI stringer in Palestine who was also a secret member of the Irgun. The stringer had learned about Operation Chick but did not know it had been postponed for an hour. Hoping to scoop his colleagues, he had filed a report minutes before 11.00. A British censor had routinely stamped his cable without reading it.

“Jewish terrorists have just blown up the King David Hotel!” This short message was received by the London Bureau of United Press International (UPI) shortly after noon, Palestine time. It was signed by a UPI stringer in Palestine who was also a secret member of the Irgun. The stringer had learned about Operation Chick but did not know it had been postponed for an hour. Hoping to scoop his colleagues, he had filed a report minutes before 11.00. A British censor had routinely stamped his cable without reading it.

American operations in South Asia… are threatening to upset [a] fragile balance between Islam and nationalism in the Pakistani military. The army’s members can hardly avoid sharing the broader population’s bitter hostility to U.S. policy. To judge by retired and serving officers, this includes the genuine conviction that either the Bush administration or Israel was responsible for 9/11. Inevitably therefore, there was deep opposition throughout the army after 2001 to American pressure to crack down on the Afghan Taliban and their Pakistani sympathizers. “We are being ordered to launch a Pakistani civil war for the sake of America,” an officer told me in 2002. “Why on earth should we? Why should we commit suicide for you?”

American operations in South Asia… are threatening to upset [a] fragile balance between Islam and nationalism in the Pakistani military. The army’s members can hardly avoid sharing the broader population’s bitter hostility to U.S. policy. To judge by retired and serving officers, this includes the genuine conviction that either the Bush administration or Israel was responsible for 9/11. Inevitably therefore, there was deep opposition throughout the army after 2001 to American pressure to crack down on the Afghan Taliban and their Pakistani sympathizers. “We are being ordered to launch a Pakistani civil war for the sake of America,” an officer told me in 2002. “Why on earth should we? Why should we commit suicide for you?”

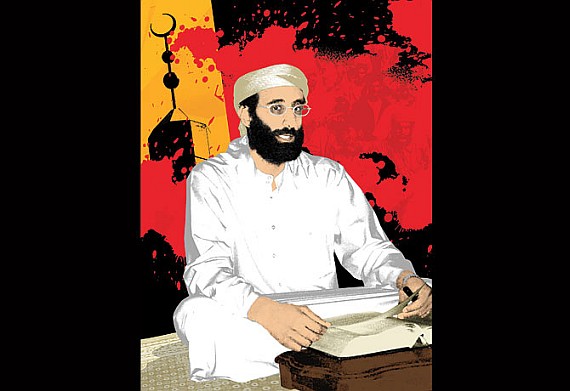

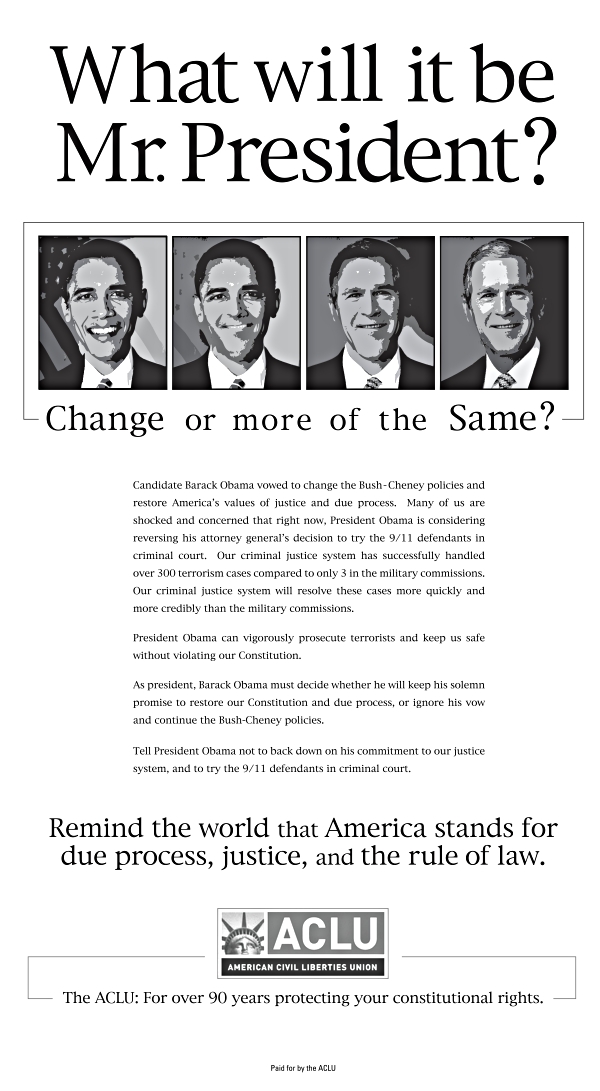

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target.

When Anwar al-Awlaki, an American born in New Mexico is shredded and incinerated — his likely fate at the receiving end of a Hellfire missile — there will be no account of the last moments of his life. No record of who happened to be in the vicinity. Most likely nothing more than a cursory wire report quoting unnamed American officials announcing that the United States no longer faces a threat from a so-called high value target. In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of

In weighing the fate of Anwar al-Awlaki, this administration would do well to remember the case of

Osama Bin Laden’s favourite son, Omar, recently abandoned his father’s cave in favor of spending his time dancing and drooling in the nightclubs of Damascus. The tang of freedom almost always trumps Islamist fanaticism in the end: three million people abandoned the Puritan hell of Taliban Afghanistan for freer countries, while only a few thousand faith-addled fanatics ever traveled the other way. Osama’s vision can’t even inspire his own kids. But Omar Bin Laden says his father is banking on one thing to shore up his flailing, failing cause — and we are giving it to him.

Osama Bin Laden’s favourite son, Omar, recently abandoned his father’s cave in favor of spending his time dancing and drooling in the nightclubs of Damascus. The tang of freedom almost always trumps Islamist fanaticism in the end: three million people abandoned the Puritan hell of Taliban Afghanistan for freer countries, while only a few thousand faith-addled fanatics ever traveled the other way. Osama’s vision can’t even inspire his own kids. But Omar Bin Laden says his father is banking on one thing to shore up his flailing, failing cause — and we are giving it to him.